This report was amended on 11 May 2023. The number of Syrian fighters currently in Libya is nearly 7000, not 5000, as an earlier version said.

Headless of the unrelenting efforts of Libya’s 5+5 Joint Military Commission (JMC) to remove all foreign forces and mercenaries from the country, several factions of the Turkish-backed “Syrian National Army” (SNA) continue to deploy fighters there, whose current number amounts to nearly 7000 mercenaries. The opposition’s SNA is resuming a practice that Türkiye started in late 2019, as it sent Syrian fighters to Libya to participate in combat alongside the forces of the Government of National Accord (GNA).

However, Türkiye is one of many sides deploying Syrians to battlefronts in Libya. Several Russian security companies have also recruited Syrian fighters from areas held by the Government of Syria (GOS) to back the Libyan National Army (LNA), led by retired Major General Khalifa Haftar, against the GNA.

According to testimonies Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) obtained in April 2023, the latest batch of Syrian mercenaries arrived in Libya in December 2022. This last transfer included fighters from various SNA factions involved in the practice of mercenarism and several under-18 children.

Notably, the continued presence of mercenaries in Libya is at odds with UN calls to withdraw all foreign forces from the country and repeated emphasis that such presence poses a grave threat to security in Libya and the region. These calls continue to be discarded by Russian security companies, the SNA, and Türkiye. On 21 June 2022, Türkiye’s parliament approved a motion extending troop deployment in Libya for another 18 months starting on 2 July 2022.

The motion remains relevant in the context of widespread mercenarism among the SNA factions because the Turkish military maintains effective supervision over Syrian mercenary camps in Libya, and the Turkish authorities fly Syrian mercenaries there.

In this report, STJ reveals that several SNA factions continue to recruit and send children to mercenary camps in Libya. Additionally, STJ investigates the current status of the Syrian fighters in these camps after combat has abated. The report monitors breaches of the agreements the fighters concluded with the recruiters before they left for Libya, highlighting the role of connections and nepotism in mercenary camps and how they affect the fighters’ access to leave.

Additionally, the report sheds light on the punishment that fighters, as well as child recruits, face if they violate the orders of their commanders.

The report builds on interviews researchers with STJ conducted with six military sources in Libya, including two fighters from two different SNA armed groups, two children who arrived in Libya in the December 2022 batch, and two high-ranking officers who spoke about several violations committed by some factions, including smuggling members of the “Islamic State” (IS) from Syria to Libya.

Additionally, the report documents the unabating profiteering on the side of commanders of several SNA factions in Libya from fighters whose primary motive to become mercenaries remains material gain. Moreover, the report exhibits the expansion of the scope of previous violations involving several fighters and commanders. In addition to drug trafficking, the sources STJ interviewed confirmed that second-rank officers are also involved in human trafficking operations from Libya to Italy.

Keeping tabs on the presence of Syrian mercenaries in Libya, the digital forensic expert with STJ posted a tweet on 16 March 2013 showing images of the Suleiman Shah Brigade (also known as al-Amshat) celebrations on the 12th anniversary of the Syrian revolution. The footage corroborates that the brigade held similar festivities in Libya’s Janzour Military Camp for the third year in a row.

Fighters with No Connections

STJ interviewed a fighter from the Northern Hawks Brigade (source 1)—stationed in the Suq al-Khamis Camp. The fighter said that recruit replacements and leave turns are subject to a quota system:

“The last batch of fighters arrived in Libya in December 2022, consisting of 150 militants. For instance, ten were from the Northern Hawks Brigade, instead of whom the [faction] sent ten home. Every faction is allocated a specific number of seats on the plane, commensurate with the number of fighters it has in Libya. However, most seats are reserved for al-Amshat [the Suleiman Shah Brigade], al-Hamzat/al-Hamzat, and Sultan Murad Division.”

Commenting on the conditions of recruitment and their repercussions for the fighters, the source stressed that recruiters sign contracts only with “rank officers,” denying fighters similar official agreements, which makes them vulnerable to exploitation by commanders, who tend to strip them of the incentives they were promised before their transfer to Libya. Relating to the fighters’ salaries, the source narrated:

“The factions pay fighters varying sums at their whim and without censorship. The command pays [the fighters] 230 USD in Libya and 230 USD in Syria, knowing that the total salary the fighters are entitled to is 800 USD. The lowest wage the command has paid to fighters was 200 USD. The fighters were last paid their salaries on 30 March 2023 in Hawar Kilis village. The salaries are sent to the Finance Officer in the Command Center. From there, commanders of brigades receive salaries based on the number of their recruits [in Libya]. The commanders first withhold their shares of the salaries and then distribute the remaining sums to the families of the recruits.”

Giving a matching account of the salary payment method and deductions by commanders, a fighter from the Sultan Muhammad al-Fateh Brigade/Liwa Sultan Muhammad al-Fateh (Source 2)—stationed in the Diblomasy Camp, narrated:

“[The factions] pay salaries in two installments. The first is 200 USD, paid to the fighters in Libya. Of this amount, the group commander withholds 50 or 100 USD. The second installment is 5000 Turkish Liras (TL), paid through a broker to the recruit’s family in Syria. [The second installment] takes two to six months to arrive [in Hawar Kilis].”

In addition to profiteering, the commanders spare no means to subjugate the fighters. For this purpose, the commanders tend to use the dire living conditions of the fighters’ families and their tight finances against them while also maltreating the family members who experience various forms of abuse upon picking the salaries up. Commenting on the factions’ treatment of families, Source 1 narrated:

“[The families] can pick up salaries only from Hawar Kilis village, which remains hard to reach for most of them. When they arrive there, family members are forced to wait in humiliation outside the camp in Hawar Kilis for hours. They are not assigned an appropriate [waiting] place and hear insults thrown at them.”

While degrading treatment has become a routine part of the payday for the family members, primarily women, who collect the salaries, these members also suffer the wrath of commanders. According to Source 1:

“Most of the [fighters’] families live in IDP camps, under challenging conditions with no one to support them. Therefore, the fighter’s wife is often delegated to take the salary while raising the children and meeting their needs. In case of disagreement with a fighter, his commander would threaten to deny his family access to the salary.”

Source 1 added that the factions’ commanders often confiscate the fighters’ cell phones and imprison them without informing their families. Consequently, the families grapple with worry and fear while at a loss for the means to know the fate of their sons.

While salaries are thus weaponized, the leave issue remains the vaguest part of the mercenaries’ experiences, particularly in the absence of contracts. Compared to commanders, who are prioritized in visits home, most fighters are not offered information about their leave terms. In this regard, Source 1 narrated:

“Leaves do not have specific schedules. Fighters must spend at least one year in the camp before their names are on the replacement lists. Some fighters have been in the camp for over two years but still have no idea when they will be leaving.”

The source added:

“In February 2023, following the quake in Türkiye, an aircraft, referred to as the affected persons’ carrier, was sent with a Turkish team. The team toured all the camps to record the number of fighters whose families had been affected by the quake and register their names to transfer them to Syria. However, no one has left the camp yet.”

Regarding the leave issue, Source 2 revealed that fighters struggle with preferential treatment:

“For the past three months, constant talks about a Turkish plane have occurred. However, no carrier has yet been sent. In Syria, [recruiters] agree with the fighters on an enlistment term of six months. Once the fighter is in Libya, control over the leave is left for the commander, often affected by his mood and [the fighter’s] connections. Aircraft that transfer fighters back to Türkiye do not have definite arrival dates. When an aircraft arrives, each military station is entitled to send back 30 fighters—five of the command, 20 close to the command, and five chosen arbitrarily.”

The source added:

“Some fighters have been here for two years and one month and have not gone on leave once. There was a batch of 60 fighters; 45 got leaves because they had connections, and 15 were left behind because they had no one to back them. Notably, high-ranking officers get to leave every six months. On Friday, 31 March 2023, a plane is supposed to land in Mitiga Airport to fly fighters to Syria.”

The source stressed that the command punishes any attempt on the part of fighters to have access to leave through connections:

“Should a fighter communicate with someone he knows within the National Army in Syria to [broker his return to the country], his cell phone will be destroyed. He will also be imprisoned and banned from leaving.”

Child Recruits and Nepotism

According to the information STJ obtained from the sources, there are nearly 600 child recruits in the Syrian mercenary camps in Libya. The children are all under-18.

STJ spoke to two of these children, who arrived in Libya in mid-December 2022. They left the Afrin region sometime before 12 December and headed for Gaziantep in Türkiye. From there, they were next flown to Istanbul Airport onboard a military cargo plane and then to Tripoli in Libya onboard a civilian plane.

Notably, money is the motive underlying these children’s enlistment with the SNA factions deploying mercenaries. Some seek a source of income after they lost their breadwinners; others accompany their fathers in Libya “to boost [the fighters’ count] and for the financial benefit,” according to Source 1, who confirmed the presence of at least ten children in the Suq al-Khamis camp. The source added:

“Most of these children are close to the command. No one can approach them or even talk to them. They are only 17 years old. They stay at the command’s building. They are exempted from all duties, the morning roll call, and training. They are paid salaries of 500 USD.”

For further insights into the duties of the command-affiliated children, STJ spoke to (Source 3), who has been identified as a 16-year-old child. The source is the son of a first-rank officer from the Sultan Muhammad al-Fateh Brigade/Liwa Sultan Muhammad al-Fateh. He has been deployed to the Diblomsi Camp with other members of the group who arrived in Libya recently. Addressing his responsibilities within the camp, the child narrated:

“After the war abated and lucrative salaries shrank, more children sought Libya. As sons of commanders, we are not assigned duties. We primarily play PUBG and football. We spend most of our time having fun. We are prohibited from leaving the camp. However, my friends and I leave when our fathers go outside; we attend Turkish or Libyan meetings, for instance. We also visit the marketplace just for a change. Nevertheless, we never leave alone; it is always with our fathers. In general, most of the young boys are here with their fathers.”

The source added that a small number of the children who accompanied him—sons of people with connections or ‘martyrs’—are assigned “administrative tasks and chores, such as cooking, cleaning, doing dishes and washing clothes.”

However, chores are only a part of the daily tasks assigned to the second child recruit (Source 4). The source is 15-year-old and is the son of a commander slain in Libya. This child was deployed to the Suq al-Khamis Camp. Highlighting the reasons that lured him to join the Northern Hawks Brigade, he narrated:

“After my father’s death, my family no longer had a breadwinner. Therefore, my mother reached out to high-ranking officers in the Northern Hawks Brigade to work with them and get a salary in return. They told her: ‘We could take him to Libya for a year. His salary would be better, and your living conditions would improve. Currently, there is no war there. God willing, it would even be safer than Syria.’ My mother accepted for that reason, and I went to Libya.”

The source said there are approximately 30 child recruits in his camp. They are all under-18 and carry out a wide range of duties:

“We have daily tasks, including fitness training. We are trained on using many weapon types—guns, AK-47, PKC machine guns, DShK, 14.5 and 23 anti-aircraft systems. We also have night duties, such as guarding the camp. Additionally, we have chores, including cleaning the camp, cooking, and doing dishes. The young man who disobeys the orders, takes the guard duties for granted, gets caught playing with his cell phone or taking selfies, gets his head shaved and is imprisoned for three days to two weeks.”

Torture in “Hell”

In the mercenary camps, the fighters are also tortured by commanders. Torture has direct and indirect manifestations, which affect all the dimensions of the recruits’ lives. Fighters are not only locked in the camps—because leaves and replacement turns are mainly dependent on personal connections and the temper of commanders, but they also grapple with the poor quality of services the command offers them, including food rations and healthcare.

Camps get food supplies once a week. The allocations are deficient, and they barely sustain the fighters for a few days. This forces the recruits to buy food at their own expense. Commenting on the nature of the supplies, Source 1 narrated:

“Every Thursday, a ration of vegetables and foodstuffs comes to the camp, which hardly covers [the fighters’ needs for] three days. Moreover, most of the food is inedible. Consequently, the recruits are forced to buy food from the al-Nadwa Supermarket for twice the regular prices and spend their entire salary there.”

In a matching account, Source 2 stressed that the commanders use meager food portions and poor quality to further profiteer from the fighters. He added:

“A communal kitchen cooks for all the fighters. Most of the meals are bulgur and sometimes inedible frozen chicken. Last year, the food allocations were reduced for three months, during which the fighters lacked even bread and began eating moldy loaves. Inside the base, there is a command-operated supermarket. The shop is used to take advantage of the fighters because the prices of the sold items are five times higher than their price outside the base. The fighters are forced to buy from that shop due to the poor quality of the food [they are allocated].”

The fighters are coerced to make purchases from the command’s shop exclusively because they are banned from leaving the camp’s grounds while also put under strict security controls inside it. Commenting on the situation inside the Suq al-Khamis Camp, Source 1 said:

“In May 2022, there were orders from the Turks to prepare for an upcoming battle. A great security tightening accompanied the orders. Several surveillance cameras were installed in the camp, in addition to the presence of a specialized 24-hour monitoring team. Additionally, the individual weapons of the fighters were withheld.”

According to Source 2, fighters in the Diblomsi Camp suffer similar controls. He narrated:

“[The fighters] are completely locked inside the base. No fighter can go near the command building or talk to the building’s guards or the commander’s attendants. Fighters are allowed to leave the base only in health emergencies, taken to a Turkish military hospital under strict watch to prevent them from escaping.”

Expanding on health services, the source added:

“There is a medical facility inside the base. It has only painkillers to offer the fighters for any illnesses they suffer.”

Notably, the fighters are taken to the Turkish military hospital, especially after they are tortured. In each mercenary camp, there is a prison where fighters are subjected to various methods of torture, including being shot in the foot. Commenting on torture, Source 2 recounted:

“There are various torture and humiliation methods in the prison, such as shaving the fighter’s head, stuffing him into a tire, electrocuting him, and even shooting him in the feet. The fighter is taken to the Turkish hospital when shot in the feet. The hospital report then would say the bullet was fired by mistake as the fighter cleaned his weapon.”

The commanders imprison and torture fighters as a punishment for several breaches, primarily taking their cell phones out of their dorms, fighting among each other, and criticizing the treatment of the command. Source 2 relayed the story of one of the fighters imprisoned and tortured for challenging a trainer in the camp:

“Once, the trainer yelled: ‘Move on you fools!’. A fighter called him out, saying, ‘Why not say move on you animals!’. Consequently, they imprisoned him for four days, shaved his head, and tortured him using a tire.”

The source added that the fighter described the situation as “hell, where no fighter has dignity and where most of the fighters are asking for drugs and hashish to cope with the circumstances they are experiencing.”

Ongoing Violations

STJ obtained a testimony corroborating that previously documented drug trafficking by SNA fighters between Syria and Libya continues. A high-ranking officer (Source 5) from Suleiman Shah Brigade (also known as al-Amshat) said that fighters smuggle drugs in their military bags and weapons:

“Some of the drugs, such as captagon, H-Bose, hashish, and cocaine, which are imported from southern Lebanon and considered to be of high quality, are smuggled from Syria to Türkiye and finally to Libya. These drugs are sold in the Libyan market at twice the price of the rest of the types that enter the country because of their quality.”

The source highlighted that the Turkish military inspections tend to miss the trafficked drugs because the searches focus on the fighters’ clothes but not their weapons. In addition, the searches are done manually, “not with electronic devices or detection dogs.” The source elaborated on the drug transfer method:

“Drugs are smuggled inside the rifle butt and ammunition or in a military backpack. For example, the bag is unstitched and filled with approximately 4,000 captagon tablets. In addition, the rifle butt is stuffed with hashish paste, while bullet casings are filled with H-Bose instead of gunpowder.”

The source confirmed that the trafficking operations involving several SNA faction commanders are not limited to drugs; some commanders also engage in human trafficking. He narrated:

“Despite the difficulty of smuggling [migrants] through the shores of Tripoli—where the factions of the Syrian National Army are active, compared to Benghazi—where Haftar’s forces and mercenaries recruited from the areas of the Syrian regime are deployed, several second-rank SNA commanders work as brokers. Their role is limited to bringing “passengers,” mostly Syrians and a few people from other nationalities. Then, the commander connects these people with human traffickers in Tripoli or even Benghazi.”

Relating to the financial dimensions of the smuggling operations, the source said:

“The smuggler receives a sum of money for each person brought to the shores of Libya whose smuggling operation succeeds. [The SNA commander] has a share of the payment as a guarantor and an intermediary between the smuggler and the person. The trafficking operations are very successful because the commander does not get paid until the passenger reaches the shores of Italy. Therefore, the commander tends to be keen on completing the operation in the best way and pressures the smuggler to be scrupulous.”

For his part, a high-ranking officer from the al-Hamza/al-Hamzat Division (Source 6) told STJ that several Libya-stationed SNA factions are involved in smuggling persons, prosecuted for several charges, from Syria to Libya. He added:

“Lately, particularly in the context of competition and recent clashes, the factions have been using security issues against each other. As a result, they are handing the security files to the Turkish intelligence and the Military Police. These files have become a source of anxiety for the factions because the Turks are pressuring them to surrender wanted persons.”

The source elaborated on the smuggling method:

“[The factions] are obtaining new identity cards, issued by local councils, for wanted drug dealers and IS militants under their protection while evading trials. Then, they transport these persons to Libya so the other factions would forget about them. All factions are involved in this practice, with no exception. Notably, the number of the smuggled persons is fairly large, particularly those from the al-Hamzat Division and the Sultan Murad Brigade.”

The source added that the commanders are also actively partaking in the weapon trade, selling the arms they seize as “spoils” following battles to Libyan forces or civilians. He narrated:

“During the latest battles, [we] confiscated many weapons from Hafter and Russian Wagner forces. Because the battles were never resumed, we had a sufficient stock of light weapons, rifles, guns, RPGs, and PKC machine guns, with a large amount of these weapons’ ammunition, called ‘soft point ammo.’ We have these extra stocks because the Turkish-affiliated Libyan forces purchased the heavy weapons and vehicles we seized. The purchase was an excellent source of funding for the faction. However, the forces refused to buy the other weapons and told us to deposit them in our warehouses for emergencies and training. This was unfair, and they should have bought these arms, especially because we are brought weapons, and our shortages are covered before every battle.”

The source added:

“There is demand for these weapons on the civilian market. Most of the Libyan locals are increasingly expressing their desire to have several light weapons in their homes. Therefore, there has been increasing demand for such arms. This encouraged most of the factions’ commanders to get some of these weapons out of the warehouses and sell them to civilians. The revenues were not distributed to fighters but rather withheld by the supervising commanders, who divided the profits amongst themselves. The fighters who protested were imprisoned and denied their salaries. Notably, the weapons are sold to civilians through Libyan brokers, who are weapons dealers.”

Syrian Mercenary Camps in Libya

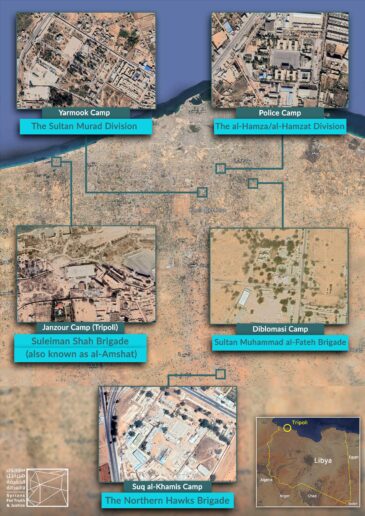

STJ geolocated five spots that SNA factions use as camps for their fighters in Libya.