In this report, Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) presents an update on the Syrian mercenary activities in the context of the Ukrainian conflict, revealing new information obtained in December and the second half of November 2022. The information corroborates that Syrian security companies continue to transfer fighters to Ukraine, operating as proxies for the Russian Wagner Group.

In the context of transfers, the sources STJ interviewed confirmed that recruiters flew nearly 300 fighters to Ukraine through three flight routes between June and September 2022.

Additionally, STJ discovered that the Wagner Group has also been transferring mercenaries from foreign para-military groups active in Syria to fight alongside the Russian military in Ukraine, along with fighters recruited from Syrian militias.

For insights on the status of deployed Syrian fighters, STJ reached out to the families of several recruits. The interviewed relatives said that the al-Sayyad Company for Guarding and Protection Services informed families of the death of their sons in Ukraine; however, it provided them with no official documents to corroborate the deaths nor delivered them the bodies.

Notably, this is not the first batch of mercenaries that Russia transfers to Ukraine. In a series of previous reports, STJ documented that security companies have recruited and transferred hundreds of Syrian fighters stationed in both Syria and Libya since the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022.[1]

Nearly 300 Fighters Flown from Syria to Ukraine

For this report, STJ interviewed several military sources within Syrian government (SG) forces between late October and early November 2022. The sources confirmed that the Russian Wagner Group continues to deploy Syrian militants to join combat in Ukraine. They added that the group flew the latest batches on 9 September, 7 July, and 5 June 2022.

Elaborating on the transfers, one of the sources, a second-class officer from the 25th Special Mission Forces Division, told STJ that the group transported approximately 300 fighters onboard an Ilyushin aircraft. The officer added:

“One flight set off from the Russian-operated Khmeimim Air Base (Hmeimim Air Base) in Latakia. The batch included 70 Syrian fighters, mostly from the provinces of Homs, Hama, and As-Suwayda. This transfer operation happened after the fighters finished a 45-day military training by officers from the Wagner group, at a camp/base in As Sayyid village, in the Furqlus area.”

The officer added that the recruits were informed of the service conditions in cases of death and injury. If fighters die in action, their bodies would not be returned to Syria, and their families would receive compensation of about 25,000 USD each. When injured, the fighters would be treated in field hospitals. Those who sustain injuries that hamper 52% of their capacities would have two choices, travel to Europe as asylum seekers or return to Syria.

Additionally, the officer told STJ that the second flight, on 7 July, left from Khmeimim Air Base, carrying 145 fighters of different nationalities. He added:

“[This batch] included 30 Syrian mercenaries from the As Sayyid village military camp, who were trained on using heavy artillery, 80 from the Syrian Liwa al-Quds (Jerusalem Brigade), an Aleppo-stationed group affiliated with the Iranian Revolutionary Guard, and 35 from Fatemiyoun militia, an Afghani group active in Syria.”

For his part, the second military source, a volunteer fighter within the 25th Special Mission Forces Division, told STJ that Russia flew another batch through Iran. The batch included 80 fighters from the 16th Division, operating under the 25th Division. The fighter added that the commander of the 16th Division is called al-Sabe’ and hails from the suburbs of Safita city.

The fighter highlighted that the Operations Officer of the 25th Division, of the Quwwat al-Nimr (Tiger Forces), supervised the transfer. He added:

“They selected 80 infantry fighters from the 16th Division. One of the recruits in this batch informed me that they were first flown to Iran onboard an Iranian Mahan courier. Next, they were relocated to Russia, and then to the 104th Base in the eastern region, particularly in Miusynsk – Міусинськ town. From there, they were taken to Melitopol city and stationed on the front there. To my knowledge, each fighter will be paid a monthly 600 USD in Russia and an additional monthly 800 USD in Syria”

Image (1) – A satellite image of the 104th Base taken in 2021. It is a Russia-operated military base in eastern Ukraine (occupied by Russia since 2014) and bears the name of the nearby Miusynsk – Міусинськ town in the Novopavlovsk region. The base matches the information the above-cited source and other sources gave to STJ.

Monitored Flights

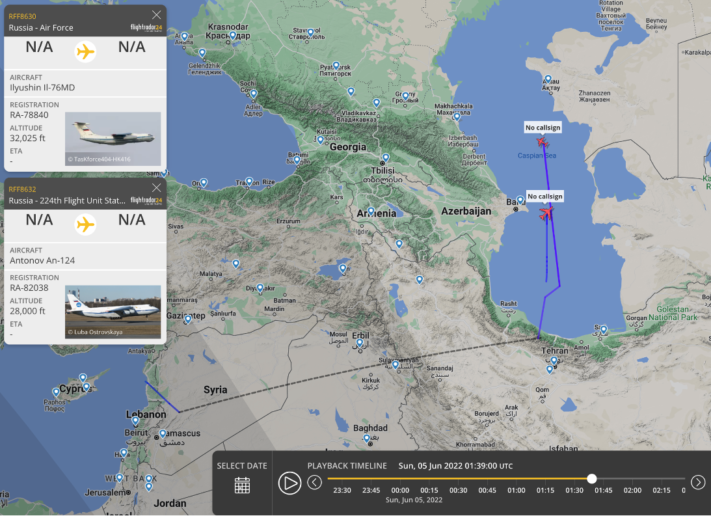

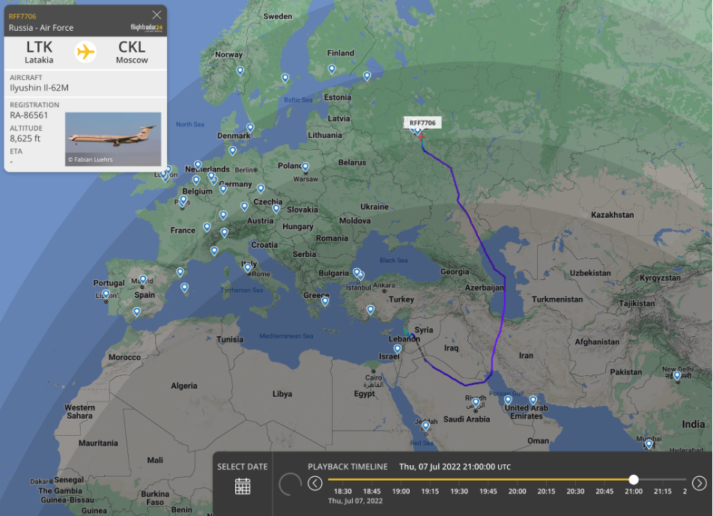

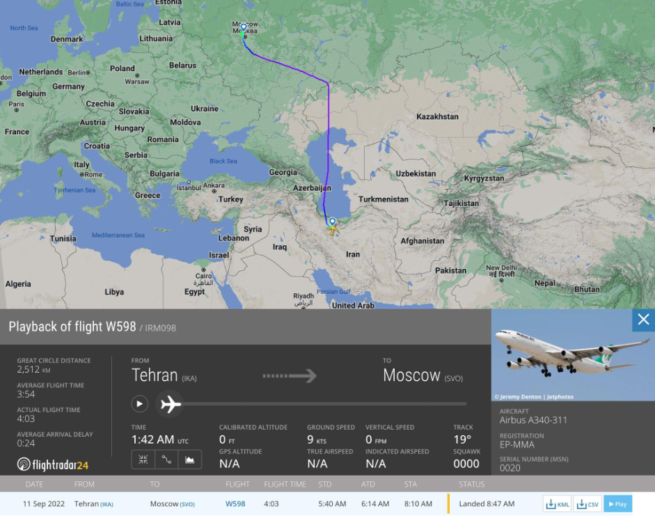

Based on the information STJ obtained from crosschecking the accounts of interviewed sources, the digital forensic expert with STJ tracked flight trajectories and had access to related logs on FlightRadar24. The expert identified three flights that matched the details relayed by the sources:

- Flight Route 1: from Syria to Russia on 5 June 2022.

- Flight Route 2: from Syria to Russia on 7 July 2022.

- Flight Route 3: A- from Syria to Tehran on 9 September 2022. B- from Tehran to Russia on 11 September.

Flight Route 1

STJ-monitored flights which demonstrate that two Russian aircraft took the Syria-Russia route. The first was an Ilyushin Il-76, with the registration code RA-78840. It took off from Khmeimim Air Base at midnight Syria time on 4-5 June and headed southeast. The aircraft was later tracked flying over the Caspian Sea and crossing into Russia in the direction of Mozdok city, which is a major military logistics center.

The second was a 124-Antonov An, with the registration code RA-82038. It was tracked flying over the Caspian Sea at around 4:00 Syria time. STJ’s digital expert believes that this aircraft also likely departed from Syria since it took the same route as the previous flight.

Additionally, the digital expert tracked nine flights to and from Syria by the aircraft coded 78840-RA. The aircraft completed two flights in January, one in April, three in June, two in July, and one in October.

At the same time, the expert corroborated at least one flight to and from Syria by the aircraft coded 82038-RA on 28 March 2022.

Image 2- Screenshot from Flightradar24 of the two flights on 5 June 2022. According to the information obtained by STJ, one of these flights at least was transferring Syrian mercenaries to Russia.

Flight Route 2

STJ’s digital expert tracked one flight which took the second route. An Ilyushin Il-62, with registration code RA-86561, was spotted taking off from Khmeimim Air Base to Moscow on 7 July 2022. The aircraft took off from the base at 18:07 PM Syria time and landed in Moscow shortly after midnight on 8 July. This aircraft was last recorded flying to and from Syria on 14 November 2021.

Image 3- Screenshot from Flightradar24 of the flight on 7 July 2022. According to information obtained by STJ, this flight was likely carrying fighters, bound to join Russia in its invasion of Ukraine.

Flight Route 3

From Syria to Tehran on 9 September

STJ’s digital expert tracked a flight by an Airbus-A300 belonging to Mahan Airlines, with the registration code EP-MNJ. The aircraft took off from Aleppo Airport at 23:44 Syria time, headed to Tehran. Notably, the expert detected nine such flights by the same aircraft over 2022; one in June, four in July, and four in September.

Image 4- Screenshot from Flightradar24 of the Syria-Tehran route. According to information obtained by STJ, this is likely one of the flights that transferred Syrian fighters from Syria to Tehran, and then to Russia.

From Tehran to Russia on 11 September

STJ’s digital expert tracked a flight by an Airbus-A340 belonging to Mahan Airlines, with the registration code EP-MMA. The aircraft took off from Tehran Airport and headed to Moscow. Notably, the expert detected 14 such flights by the same aircraft between May and mid-November 2022.

Image 5- Screenshot from Flightradar24 of the Tehran-Russia Route. According to the information obtained by STJ, this flight was likely carrying Syrian fighters transferred from Syria to Tehran, on their way to Russia.

Mercenary Deaths Kept Under a Tight Lid

Various factors make it difficult to obtain accurate statistics on mercenary fatalities. These factors include the absence of official and semi-official figures on the number of Syrian fighters deployed as mercenaries in the Russian-Ukrainian conflict and almost non-existent inputs from sources on the battlefield, as well as the tight lid on information maintained by the recruiting security companies and the fighters’ families.

Despite these challenges, STJ obtained the names of four dead mercenaries from a fighter flown to Ukraine in March 2022. The fighter is engaged in combat in the Kherson region. He said that these mercenaries died on 10 September inside the Korsor Establishment. The source added:

“The number of deaths remains unknown because Syrian fighters are deployed to various areas, including Belgorod, Nova Kakhovka, Krymsky, Kuzminki, Kadamovsky, and Kamensk-Shakhtinsky. As I observed, no fighters, dead or wounded, were returned to Syria. Additionally, there were no announcements about deaths or the recovery of dead bodies. There has been massive secrecy and reservation on this information since the beginning —and especially after the Russian retreats.”

Several families were unofficially informed of the deaths of their sons, first from their sons’ companions in Ukraine and later from the security company which recruited them. . However, none of these families was offered documents proving the deaths.

For further information on casualties among Syrian mercenaries, STJ reached out to the family of a fighter from Rif Dimashq (Damascus Countryside). This fighter was initially recruited to join combat in Libya, and his contract was renewed for the second time in early February 2022.

The family narrated that their son was relocated from Libya to Ukraine in late March 2022 and was out of reach for three months. Later, a friend of the fighter told the family that their son went missing with a whole group in June 2022. In early July 2022, the al-Sayyad Company informed the family that their son was dead. However, the company neither specified the death date nor gave the family proof of death nor delivered them their son’s personal belongings. For their part, the family held a funeral and told people that their son died in Idlib, Syria.

A relative of the dead fighter narrated the details to STJ’s researchers:

“After the young man arrived in Ukraine, he called his family twice using a cell phone he kept as loot from a raid. Back then, he told his family that they were prohibited from using cell phones or filming and that he was assigned as a sniper in Donetsk city. He went missing for nearly three months. We started inquiring about the situation from the families of the other fighters deployed to Ukraine. Later, a man [in Ukraine] told us that my relative went missing with a group during a raid. He added that they were not sure whether he was captured or dead because the bodies of fighters are not brought back from the field in that area.”

The relative added:

“We reached out to the al-Sayyad Company, which had already informed four families of the deaths of their sons. The company instructed us to claim that he died in Idlib, not Ukraine, if we wanted to hold a funeral. In the beginning, the young man’s family refused to hold a funeral or announce his death because they received no proof. We had no document nor the body. The al-Sayyad Company informed us about the difficulty of recovering the bodies of dead recruits. The company said that even when recovered, the bodies are usually buried on site because it is difficult to verify the identities of dead recruits.”

The relative concluded:

“The only piece of evidence we have about his death is information saying that he was among a group that entered a minefield. The group’s members all died and the bodies were recovered from the site two weeks later. According to the information they gave us, the number of recovered bodies matched the number of the group’s recruits. However, the bodies were mutilated, decomposed, or consisted of only pieces.”

A Legal Perspective

In 2008, Syria acceded to the International Convention against the Recruitment, Use, Financing and Training of Mercenaries of 1989 (the Convention), and did not have reservations about any of the articles on basic provisions regarding its duties in dealing with the issue of mercenaries. Accordingly, the Syrian authorities are obligated, in accordance with Article 5 of the Convention, not to recruit, use, finance or train mercenaries, represented by any of their official agencies or employees. Additionally, authorities are obligated to prohibit and punish these activities as crimes of a serious nature.

These obligations are applicable to the current Syrian context, especially since—as this report and previous publications by STJ demonstrate —the elements of the definition of a mercenary, contained in Article 1 of the Convention, apply to Syrians recruited and transferred to active fronts in combat between Russia and Ukraine. These individuals are specially recruited to fight in the Russian-Ukrainian international armed conflict (element a), they are not nationals of either country, nor do they reside in territory under the control of either of them (element c), and they are not members of the Russian or Ukrainian armed forces (element d).

Related to the two remaining elements (b and e), previous STJ reports corroborate that the underlying motive for these individuals’ turnout to contract with recruiters is material. The elements still apply even though parties/individuals within Syrian authorities are involved in the recruitments in their official capacity, and regardless of the fact that this involvement cannot be interpreted as a deployment by the Syrian authorities in an official capacity within the meaning intended by element e.

While the Syrian authorities have not been sending recruits officially, their engagement in facilitating the processes of recruitment, as well as transfer, of individuals from Syria still constitutes a violation of the essence of the legal duty prescribed by Article 6(a) of the Convention. The article obliges States Party to “[take] all practicable measures to prevent preparations in their respective territories for the commission of those offences within or outside their territories,” given that these offences— recruitment, use, financing and training of mercenaries, are at the heart of the Convention.

In addition to preventative measures, Article 10(1) of the Convention obliges Syrian authorities to enforce measures of imprisonment or appropriate criminal proceedings against persons alleged to have committed these offences immediately. Moreover, in case the alleged offenders have not been extradited, the Syrian authorities must prosecute the offenders in accordance with national laws, pursuant to Article 12 of the Convention.

Recommendations

Within this legal perspective and considering the information presented by the report, STJ recommends that:

- The Syrian authorities, pursuant to their obligations in accordance with international law, act immediately to stop all activities recruiting and transferring individuals as mercenaries from Syria, whether the party that carries out these activities is official, such as the Russian government, or unofficial, such as the Wagner Group.

- All officials found to be involved in the crimes stipulated in the Convention be held accountable, as well as any other entities within the jurisdiction of the Syrian authorities, including Wagner Group-affiliated officials.

- The International Commission of Inquiry on Syria sheds light on this phenomenon, investigates and considers it one of the main thematic concerns in its scope of work.

- Even though Russia is not a State Party to the convention, it criminalizes mercenaries and the recruitment, financing, and training of mercenaries. Therefore, relevant United Nations bodies intensify communication and pressure the Russian authorities to prevent this phenomenon and hold those responsible for it accountable.

- The Working Group on Mercenaries further focuses on this phenomenon in Syria, by requesting a country visit and allocating special sections in the annual report to represent in detail this phenomenon, its complexities, and its effects.

[1] “Russia Transfers Hundreds of Syrian Fighters to Ukraine, Including Syrian Army Soldiers”, STJ, 17 May 2022 (Last visited: 9 December 2022).

“Ukraine: Wagner Group Begins Relocating Syrian Fighters from Libya to Russia”, STJ, 21 March 2022 (Last visited: 9 December 2022).

https://stj-sy.org/en/ukraine-wagner-group-begins-relocating-syrian-fighters-from-libya-to-russia/

“Syria: Has the Recruitment of Syrian Fighters Towards Ukraine Begun?”, STJ, 4 March 2022(Last visited: 9 December 2022).

https://stj-sy.org/en/syria-has-the-recruitment-of-syrian-fighters-towards-ukraine-begun/