Executive Summary

This joint report builds on 40 testimonies and statements collected between March and May 2023 on gross human rights violations in the Afrin region in the extreme northwest of Syria.

The testimonies were collected in the aftermath of the February 2023 earthquake, obtained from quake survivors and affected civilians from the region, which was a hotspot for recurrent and large-scale violations during and after the humanitarian response to the tremors. Notably, the reporting period also coincided with the anniversary of Türkiye’s control of the region, which has been under the direct military rule of the Turkish military and several Syrian armed opposition groups for the past five years.

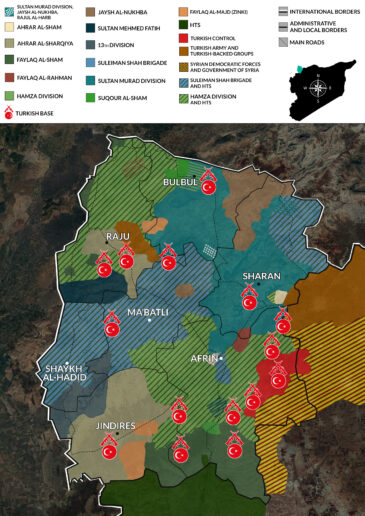

The testimonies indicate that several armed groups of the Syrian National Army (SNA), which Türkiye backs, were involved in the violations documented in this report. However, certain groups’ names appeared more frequently than others. These are the al-Hamza/al-Hamzat Division, the Sultan Murad Division, the Sham Legion/Faylaq al-Sham, the Levant Front/al-Jabha al-Shamiya, the Eastern Army/Jaysh al-Sharqiya, the Ahrar al-Sharqiya/Free Men of the East, the Elite Army/Jaysh al-Nukhba-Northern Sector, Nour al-Din al-Zenki Movement, and the Military Police, in addition to the Turkish Intelligence, cited as a perpetrator in cases of torture and ill-treatment.

Moreover, one segment of the testimonies—provided by people hailing from almost all of Afrin’s[1] districts—revealed that the perpetrators used two alleged charges as a pretext to arrest and torture several Kurdish locals, seize the properties of others, and deny them access to their homes and lands. These two charges are working with the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), which controlled the area up to 2018, and membership in the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).

Notably, the charge of working with the AANES poses a threat to a large percentage of Afrin’s residents. This risk arises from the fact that the AANES, during their multiple-year control of the region, were a de facto authority and the population’s only choice to manage their daily affairs and process essential transactions. The community in Afrin had to engage with the AANES departments to obtain authorizations and identification documents, access healthcare and education, or land jobs, such as teaching within AANES-administered schools or universities or working within their institutions.

Another segment of the collected testimonies revealed that the arrests, torture, and property appropriations the perpetrators committed against the region’s Kurdish residents were not limited to those they allegedly accused of these two charges—engaging with the AANES and belonging to the PKK. Several AANES political opponents also suffered similar abuses.

According to accounts relayed by victims of torture and property seizures, it also appears that the involved SNA armed groups have used torture methods to coerce confessions from detainees regarding themselves, their families, or neighbors.

Of the 40 testimonies collected for this report, 10 are about property confiscations. The SNA armed groups seized houses and other properties from civilian owners in Jindires and its suburbs. In some cases, the armed groups used these properties to house the families of their fighters or rent them out to internally displaced persons (IDPs) from elsewhere in Syria. However, the quake that hit on 6 February 2023 wreaked havoc in the area. It destroyed or partially damaged houses confiscated five years prior. While partially damaged structures were used for housing, destroyed structures were removed, leaving the plots on which they formerly stood barren. In their testimonies, displaced owners of destroyed homes expressed concerns over a second cycle of property seizures. They fear the empty plots will be sized under the guise of early recovery or reconstruction, robbing them of their ownership rights permanently.

Addressing another dimension of property seizures in the region, the report documents large-scale confiscations of property owned by the Yazidi community. The perpetrators expropriated several houses, shops, and olive groves owned by members of the Yazidi religion. They transformed a number into military headquarters or bases and used others to house either families of fighters or IDPs from other regions across Syria. For instance, the Levant Front/al-Jabha al-Shamiya established hegemony over the entirety of the Yazidi Bafilyoun/Baflûnê village in the Sharran district, Afrin region. The armed group denied all the village’s residents returning to their homes, and in their place, they settled down IDPs and families of their fighters, according to forcibly displaced villagers.

In addition to repurposing confiscated properties for military or housing ends, the testimonies show that armed groups in various areas across the Afrin region have used revenues from seized houses and groves to fund their activities and revealed that at least one home has been converted into a public facility by a Türkiye-affiliated civil organization.

Furthermore, the testimonies corroborate that several SNA armed groups were involved in cases of torture after they arrested or abducted victims, including a Yazidi woman and an older man. The perpetrators kidnapped and tortured the man before releasing him in exchange for a ransom. As for the woman, they arrested, tortured, and sentenced her to prison for several years. A third torture victim said he witnessed multiple rape cases in an A’zaz-based detention facility. He added that there were Turkish Intelligence officers in that facility.

The testimonies also present cases whereby the victims or survivors were the object of multiple violations by the same or different SNA armed groups. In her testimony, one woman said she was forcibly disappeared for two years and a half by the al-Hamza/al-Hamzat Division, her husband died in one of the armed groups’ detention facilities, and their property was confiscated by Suqour al-Sham Brigades/Sham Falcons Brigade. In a second case, a Kurdish civilian was tortured by fighters from the Eastern Army/Jaysh al-Sharqiya in Jindires because he demanded that the armed group return his house, which they confiscated in 2018. Militants from the same group killed the victim and his brothers on 20 March 2023 because they lit a small fire in celebration of the Kurdish New Year, Nowruz.

Notably, the geographical scope of the violations—which extends across Afrin, encompassing the control territories of several SNA armed groups—and Türkiye’s frequent disregard for calls by independent international organizations and the UN to cease these violations over the past five years present an additional indicator of the high probability that it was Ankara who gave the involved armed groups free rein to commit these violations.

The former Kurdish-majority region of Afrin has been a stage for numerous human rights violations since its occupation in 2018, which independent local and international organizations and UN entities have extensively documented. The SNA armed groups continue to perpetrate widespread and systematic violations in the region, including killing, arbitrary arrest, forced disappearance, torture and ill-treatment, looting and property confiscations, coercion of Kurdish civilians to abandon their homes, and hampering their returns to their home towns, in addition to Turkification and demographic change.

Methodology

In terms of methodology, this report builds on 40 testimonies and accounts collected by Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) in cooperation with PÊL – Civil Waves, Synergy Associations for Victims, and Lêlûn Association for Victims in Afrin. The field researchers from the partner organizations met with these interviewees in person or online. The respondents included witnesses, quake survivors, affected persons residing in or displaced from Afrin, and residents in camps and villages in Aleppo’s northern countryside or al-Hasakah province.

In terms of geographical scope, the researchers collected testimonies from residents or IDPs in six out of the seven districts in the Afrin region. Notably, 10 accounts were brought from Jindires city and its suburbs, given that it was one of the areas worst hit by the quake on 6 February 2023.

Additionally, the field researchers spoke with 10 Yazidi survivors from different villages across the region, including Bafilyoun/Baflûnê—entirely controlled by the Levant Front/al-Jabha al-Shamiya. Moreover, the researchers interviewed six torture victims, including women and old men. The survivors hail from different religious backgrounds; several were Muslims, two Yazidis, and one Christian. This group suffered other violations besides torture.

To verify the data collected, the partner organizations matched information and visuals provided by the respondents with open sources and linked them with satellite imagery.

For context, the report includes open-source information and visuals on violations over the past five years. This information intersects with relevant reports on these violations published by STJ and other Syrian and international rights organizations.

Notably, parts of or full testimonies have been withheld, and this report only refers to the violations and broad stories they contain. Moreover, the respondents are quoted under aliases upon the request of some and to protect the rest and their relatives from potential reprisal—especially since multiple testimonies show that the involved SNA factions have threatened the family members of the victims.

One of the entirely withheld testimonies provides the details of the death of a civilian. The victim was killed under torture in the detention facility of an SNA armed group. The victim’s family said that he was first arrested by Turkish Intelligence. A second concealed testimony narrates the details of the arrest of a woman. Her family said their daughter was tortured and subsequently developed amnesia before she was sentenced to several years in prison. A third retained testimony is of a case whereby a civil organization confiscated property owned by an IDP and converted it into a public facility.

Notably, the Afrin region witnessed two incursions by the internationally designated Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) in 2022. The HTS entered the region in support of certain SNA armed groups against others. The latest HTS invasion into the area re-demarcated the area’s military map, whereby the al-Hamza/al-Hamzat Division and the Suleiman Shah Brigade (also known as al-Amshat) established their presence in the region at the expense of the SNA 3rd Legion, the backbone of which is the Levant Front/al-Jabha al-Shamiya.

The territorial remapping had an impact on the victims and people affected by property confiscations. In their testimonies, these respondents frequently confused the names of the involved armed groups and had trouble identifying which faction occupied their property first because control over their villages shifted from one group to another as a consequence of the HTS entries. Additionally, several respondents said they have scarce information about their property because they have limited contact with their neighbors who remain in the villages, fearing their mobile phones and fixed lines are being monitored.

Large-Scale Property Seizures

One set of the collected testimonies demonstrates that civilian property confiscations occurred in almost all of Afrin’s districts. Additionally, the testimonies show that working with AANES and membership in the PKK were the allegations driven against multiple civilian Kurds from the region, on the grounds of which the involved SNA armed groups confiscated their property. Notably, these allegations can be used against a large segment of Afrin’s population, for the AANES institutions were the residents’ only chance to secure jobs for years.

Another set of the collected testimonies shows that the properties of civilian Kurds were also confiscated, although they had no verified ties with the ANNES civil or military institutions. Moreover, the testimonies demonstrate that confiscations were so widespread that the armed groups even seized entire or large swathes of the region’s villages—along with the properties, houses, and agricultural lands they encompassed—while locals remain banned from returning to their original places of residence in these villages even though five years have passed since the armed groups controlled the region.

| Several victims interviewed for this report believe that their Kurdish ethnicity is the primary reason that Türkiye-backed armed opposition groups have confiscated their and other Afrin locals’ properties. |

In Bulbul district, north of the Afrin region, interviewed IDPs said that the al-Hamza/al-Hamzat Division controls the town center, where fighters have embarked on large-scale looting. Under the pseudonym Haroun Muhammad, an IDP from the district narrated how he obtained footage documenting the division’s seizure of his properties:

“After we fled Afrin, an Arab IDP, who said he hailed from Homs province, reached out to me. He called himself ‘a welldoer’. He sent me two photos of my bulldozer. On it was spray-painted the name of a commander from the armed group that had seized my properties in Afrin. The man said the phone number on the machinery helped him contact me and share the images.”

Haroun, who today lives in Aleppo’s northern countryside with his family, added:

“The al-Hamza fighters looted all the house’s contents, including the furniture and appliances, along with 100 [olive] oil tins. They also unhinged four solar panels and three batteries. Additionally, they confiscated my [Mazda Pickup] truck, which is being used by the division’s security unit, and [Baker] bulldozer.”

The victim provided STJ with photos of the bulldozer confiscated by the al-Hamza/al-Hamzat Division. The pictures show the name of the commander from the division, written on the machinery.

Haroun spoke about how the al-Hamza/al-Hazmat Division used his house:

“A commander within the al-Hamza armed group converted my house into a post for [his activities], given its massive area. Moreover, the group had seized six of our groves, cultivated with olive trees, grape vines, and vegetables. The pretext was that two of my sons worked with the ANNES institutions.”

Also in Bulbul district, a second Kurdish IDP had lost all his properties after SNA armed groups controlled his village of Sheik Roz/Shaikhourz. Using a pseudonym, Asaad Yousef narrated:

“I lost my house and an olive mill. In 2013, an investor transformed the mill into a textile factory. Additionally, [I lost] a piece of land planted with nearly 500 olive trees on the road to the adjacent A’bodan village.”

Living in a village in Aleppo’s northern countryside, Asaad disclosed the reasons why the armed groups prevented his village’s people from returning to their homes:

“The Turkish military, the Elite Army/Jaysh al-Nukhba [Northern Sector], and the Northern Hawks Brigade controlled our village, which consists of three parts: upper, middle, and lower. People from our sector of the village are banned from returning. However, they allowed the residents of the middle and lower sectors to return a year ago, while we, the people in the upper section, are still struggling with the ban. The reason is that Turkish soldiers are deployed in our [section], protected by the two armed groups through checkpoints across the village.”

He added:

“My house and mill were bombarded during the attack on our district. The electrical wires were ripped out of the walls and stolen. Additionally, all our belongings in the house and the mill were seized on the pretext that I belonged to the PKK. Moreover, fighters from the controlling armed group tore out the steel bars from the mill’s ceiling.”

A third Kurdish IDP said that the Elite Army/Jaysh al-Nukhba-Northern Sector had seized his family property in the Sharran district. Opting for the alias Ahmad Omran, the young man narrated:

“The most painful experience, which still sticks in my mind, happened when we were about to flee our village. My father placed a copy of the holy Quran in a visible place on the TV set. When I asked him why he did that, he replied, ‘God forbid, should they enter our house, knowing that we are Muslims like them might prevent them from burning our home down or looting and robbing its contents.'”

The young man, whose family has been living in Aleppo’s northern countryside for the past five years with several other IDP families from Afrin, added:

“My father is a retired teacher. For an income, he relied on profits from olive groves and vineyards he had. I am the oldest of my siblings and was in high school when the incursion into the Afrin region happened. The Elite Army/Jaysh al-Nukhba-Northern Sector seized our house and a nearby home, which my father had bought from my uncle the previous year. Shortly after the armed group controlled the village, they brought trucks and started looting the appliances from the houses. Additionally, our house’s doors and windows were unhinged, and electricity lines were ripped out of the walls. Our two houses remained unoccupied for a while before [the army] settled the families of two of its fighters there. The families reinstalled the doors, windows, and electrical wiring in the two houses.”

The young man stressed that the army had no reason to seize their properties. He said:

“The fact that none of my family members had worked with the AANES institutions did not prevent the armed groups from confiscating our properties. Additionally, the torture that one of our neighbors had suffered at the hands of the controlling armed group when he went back made us give up on the idea of returning to the village.”

Public Facilities Were Also Seized

In the lower neighborhood of Jindires city—one of its most ancient areas—affiliation with the PKK and the AANES were also blanket charges that the armed groups used to justify property confiscations. Using the alias Siwar Shaikho, a civilian Kurd said:

“My father’s properties were confiscated after they were classified as owned by the AANES since three of our family members worked within AANES institutions. The Sham Legion/Faylaq al-Sham expropriated two out of three plots of land we had and handed them over to their agents from a nearby village. Another armed group expropriated the third plot, but I am unsure whether it was the Eastern Army/Jaysh al-Sharqiya or Ahrar al-Sharqiya/Free Men of the East.”

Additionally, Siwar mentioned the names of multiple armed groups that took turns confiscating two houses owned by his family over the past five years. He narrated:

“First, the Nour al-Din al-Zenki Movement took over our house. The armed group’s fighters looted all its contents, including the furniture. Three months later, the Jindires control map changed, and the Sham Legion/Faylaq al-Sham took our house. The legion housed the families of three fighters in the house; they hail from Eastern Ghouta. Since then, the house’s features have started to change. Four new buildings were built in our house’s yard. Currently, families of the Military Police officers are staying in the house, but we do not know how many.”

He added that the controlling armed groups also seized the facilities of a high school near his family’s two confiscated homes. He said the school was extensively damaged during the Turkish invasion of the Afrin region:

“On the other side of the road, across from our house, stood the al-Shuhadaa [Martyrs] School, [called Martyr Ronahi High School under the AANES]. The school was bombarded during the incursion and levelled to the ground. Then, housing for the Military Police was established in its place.”

The seizure of the school’s site and the construction of the police housing on its remains were not the only cases of public facility confiscations in the city. Siwar said:

“Once they had control of the city, the armed groups moved quickly to clear the debris that the Turkish shelling had left behind. The facilities of a government-operated [olive] mill were entirely cleared out, along with the debris of a house owned by one of my father’s cousins. The cousin’s house was completely destroyed, while half of his son’s neighboring house collapsed. [The armed groups] turned the area into a square.”

Property Seizures Expanded to Jindires’ Suburbs

Similar to the city, Jindires’ countryside witnessed rampant confiscation of displaced villagers’ properties by the predominant armed groups. According to a testimony obtained by the field researcher with PÊL – Civil Waves, one of the Turkish-backed opposition armed groups has seized several hectares owned by two civilians in one of the villages, administratively affiliated with Jindires. The owners refused the low sums the group offered them to rent or buy their pieces of land, despite which the group transformed the plots into a military outpost.

In Kafr Safra village, near Jindires, the Liwa Samarkand/Samarkand Brigade seized several houses owned by displaced villagers. According to the information collected by the field researcher with STJ, one SNA commander alone confiscated six houses belonging to Kurdish locals—who fled the village after the Turkish military and armed opposition groups controlled the Afrin region in 2018.

Similar property seizures were documented in other villages in Jindires, including Ras Aswad/Fqiaran. Using the pseudonym Muhsin Salim, a Yazidi IDP narrated:

“The person currently living in my house is an Arab from Homs. He broke the locks and settled in. However, I am unsure if he was involved in the looting or not. Additionally, the armed group controlling our village had cut down 25 of my 50 olive trees, just as they axed numerous trees across the village.”

Victims of Multiple Violations

The testimonies show that several of the interviewed victims and survivors were subjected to multi-layered violations. Using a pseudonym, Shireen Nasser, a Kurdish IDP from al-Ras al-Ahmar/Qizilbash village in Bulbul district, spoke about the abuses she and her family suffered at the hands of SNA-affiliated armed groups, even though none of them had ever worked with AANES. She narrated:

“We fled Afrin to Tell Rifaat. My fiancé and I held our wedding there. Three months later, we decided to return to Afrin. At the time, the armed groups had confiscated our home and brought in the family of one of their Arab fighters. The armed groups seized numerous other houses in the village.”

About the charge on which she was arrested, she said:

“My husband was arrested in Afrin. I spent three months searching for him until I was arrested for charges I never exactly understood. They told me, ‘You are not his wife. You rather have come here to send information to the administration and the party by luring us with your beauty.’ [They accused me of this] even though I had never worked with the administration or any other entity because I was too young. I spent two years and a half in prison.”

About her husband’s fate and the conditions surrounding his suicide within an SNA detention facility, she narrated:

“A released inmate told me my husband committed suicide because he could no longer tolerate the torture. However, we still have not received his body. That inmate was in the same prison ward with him. He said he died by hanging in the Afrin prison [run by the Sultan Murad Division], a day before his planned transfer to the prison operated by the Turkish Intelligence, called al-Baradat Prison. The prison is outside Afrin city, near the quarries in Ersh Qibar village.”

Notably, Shireen is one of eight Kurdish women whose whereabouts were disclosed by mere chance in May 2020. The young women were discovered after a group of indignant civilians stormed the headquarters of the al-Hamza/al-Hamzat Division in downtown Afrin. The civilians attacked the military center after fighters from the division attacked shops, killing and injuring no less than five civilians in the area. Shireen and the other detained women were freed after the news about their incarceration in the center went viral on social media and was then covered extensively by media outlets.

In August 2020, STJ published a report revealing the details of the incident and the stories of the women whom the division had forcibly disappeared for an entire year. One of them gave birth inside.

Armed Seizures

Using a pseudonym, Sawsan Tahsin, a Kurdish IDP from a village in the Shaykh al-Hadid district, narrated how the al-Waqqas Brigade confiscated her in-laws’ house. She recounted:

“We left the city after the armed groups took over Afrin in 2018 and returned to our village immediately once the roads were reopened. [Arriving there], we discovered the al-Waqqas group had looted our house and others in the village. A few hours after we arrived, the group’s fighters showed up and expelled us by force. They threatened to kill my father-in-law and put a rifle to his head. Later, they used the home to accommodate the Arab family of one of their fighters.”

Sawsan today lives in a rented house in Afrin city because she and her family still cannot access their home. They remain displaced even though the al-Waqqas Brigade lost control over their village in late 2022. She said:

“Our house remained under the control of the al-Waqqas Brigade for three years. Then, the armed group in charge changed, and al-Amshat took control of our house. When we talked to [al-Amshat] about reclaiming our home, their fighters demanded we pay [them] an unaffordable sum in return.”

Violations Against the Yazidi Minority

Several sources prove the Yazidi community’s decades-long presence in the Afrin region. However, the community’s ancient roots in the area did not protect them from the policy of property seizures. Additionally, over the past few years, the handful of Yazidis who remained in Afrin have become vulnerable to an array of violations, which continue to target them as individuals and as a cultural and religious group, according to numerous reports by rights organizations. In an April 2022 report, STJ documented the deliberate detonation of the Yazidi Cultural Union’s building by fighters from the SNA 2nd and the 3rd Legions. The fighters also destroyed the Lalişa Nûranî monument and the Zoroaster statue within the building’s garden.

Moreover, the majority of the Yazidi shrines and cemeteries have been exhumed, vandalized, and demolished in more than one village. In their September 2020 report, the International Commission of Inquiry on Syria said, “Several Yazidi shrines and graveyards were deliberately looted and partially destroyed across locations throughout the Afrin region, such as Qastel Jindo, Qibar, Jindayris and Sharran, further challenging the precarious existence of the Yazidi community as a religious minority in Syrian National Army-controlled regions, and impacting both the tangible and intangible aspects of their cultural heritage, including traditional practices and rites.”

Furthermore, several collected testimonies demonstrate that Yazidis were denied practicing their religious rituals, accused of kufr (impiety), and their women coerced to abide by the Islamic dress code. In some cases, they were forcefully urged to convert to Islam, and in others, they were made promises that they would be given back their seized properties should they convert.

Bafilyoun Village Grab

Yazidis settled in 22 villages across the Afrin area, with a population of 25,000 to 30,000 people. However, sources estimate that their count has fallen below 5,000 people since SNA armed groups took control of the area in 2018.

Several testimonies collected for this report show that the bulk of Yazidis who remained in their villages were old people, and only a few chose to return after they fled their areas during the Turkish incursion. Additionally, the interviewees said that the Levant Front/al-Jabha al-Shamiya established hegemony over the entire Bafilyoun/Baflûnê village in the Sharran district and housed several Muslim Arab families of their fighters and IDP Arab families in the Yazidi homes they seized there.

The field research with STJ interviewed the displaced Yazidi Walat Mannan in al-Qahtaniyah/Terbasbiyah town in Qamishli/Qamishlo’s eastern countryside. Hailing from Bafilyoun/Baflûnê village, he narrated:

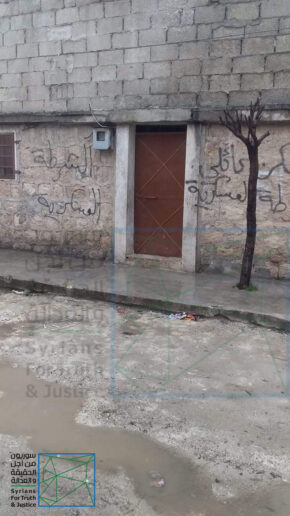

“I have lost all my property in the village, including the family home, a piece of land with over 3,000 olive trees, and two houses in the al-Ashrafiyah neighborhood in Afrin city—mine and my brother’s. I have no idea who is living in our village house. No resident of the village is yet allowed to return. The Military Police have taken over my house in al-Ashrafiyah and have written the phrase ‘a family residence for the military police’ on its walls. The house is currently occupied by two Arab armed brothers from Aleppo.”

The victim provided STJ with several photos of the phrase spray-painted on his house’s walls.

On the challenges his family suffered after they were forced to flee the Afrin region, he said:

“I still remember the scattered remains—the hands and legs—we saw while passing through Ain Dara village, south of Afrin. The scene followed an airstrike on a civilian car carrying women and several sheep. I covered my son Mirvan’s eyes so that none of that scene would be caught in his memory. Because my father had cancer and my mother was blind and had Alzheimer’s, we had to drive our car quickly, heading to the Jazira region. We managed with extreme difficulty. Later, we had to relocate to several cities until we settled in Ma’bada/Girkê Legê town in al-Hasakah’s countryside and remained there for two and a half years. My parents died there, only 20 days apart.”

Walat believes their displacement from Afrin was the primary cause of his father’s death, refusing to attribute his loss to cancer since his father had been struggling with the disease for years, and his health only deteriorated after they fled their village. He also listed the names of several elderly relatives, neighbors, and acquaintances who died over the past years due to distress in the IDP camps or in unfamiliar towns and villages that could not help them forget their villages and olive groves.

Like Walat, a second IDP from Bafilyoun/Baflûnê village lost his house after the armed groups controlled the area. Using a pseudonym, Hannan Salmou narrated:

“Two of my brothers and I lost three adjacent houses and some 1,800 olive trees. These are still registered under the name of my late father. They were seized by the Levant Front/al-Jabha al-Shamiya.”

He added that the Front continues to deny the villagers access to their homes:

“The faction does not allow our village’s people to return. Five families tried to return about two years ago but were dismissed. Therefore, I had no choice but to stay in al-Ahdath village, where I live with my family. However, after the earthquake, I had to stay in a tent that I set up across from the house after it was seriously damaged.”

Properties Confiscated for Military Purposes

In the village of Basufan, many residents also lost their properties, according to the Yazidi brothers Shirwan and Shiraz. In two separate interviews, the brothers cited the Sham Legion/Faylaq al-Sham as the group that seized their properties. The legion expropriated Shirwan’s villa and Shiraz’s house, turning both structures into military centers. In addition to the contents of their houses, which the legion looted, the brothers lost agricultural pieces of land and olive groves.

On the seizure of a piece of land the brothers jointly owned, Shirwan said:

“In July 2019, the armed group uprooted nearly 1,000 trees owned by villagers, including 100 olive trees I owned. When a delegation from the village went to file a complaint, the [armed group] told them the area where the trees had been logged would become a base for the Turkish military, saying, ‘it is for the common good.'”

In the neighboring village of Qastel Jindo—controlled by the Levant Front/al-Jabha al-Shamiya—another Yazidi IDP lost her home and now lives with her family in Aleppo’s northern countryside. Using a pseudonym, Asmaa Hasan narrated:

“We had a house in the village. Next to it, there stood my grandfather’s home, where my uncle and three aunts lived. Additionally, we owned some 2,000 trees, including 1,000 olive trees, and a house in Afrin city. All were seized after they were looted. Later, we learned that the armed group in control of the village had turned one of our homes into a military headquarters. Moreover, a person from A’zaz city has settled in the other house, while a displaced family continues to live in the one in Afarin’s al-Ashrafiyah neighborhood.”

About their house in the village, she added:

“Even though I do not know the name of the armed group in control, we know that the house has been converted into a military center.”

Also from Qastel Jindo village, another Yazidi IDP spoke about his situation after he lost his property. Using a pseudonym, Hamid Yousef recounted:

“This is the sixth time I have changed my rented house during over five years of displacement, even though I own a house. I also have five shops and a plot of land planted with 3,500 olive trees and grape vines in my village, in addition to two apartments and two shops on the ground floor in Afrin’s al-Ashrafiyah neighborhood. I have lost them all.”

The victim provided the partner organizations with a video, saying it was shot across from his shops in Qastel Jindo village. The video was posted on social media as the Sham Legion/Faylaq al-Sham took over the village. It captures high-spirited fighters, one of whom appears to be making derisive comments about Yazidis and mocking names common to the community: “Here is Qastal. And here are the shops of the pigs Abu Sako and Abu Kako”.

Addressing the party involved in his property confiscation, Hamid added:

“I remain unsure who exactly is living in my house or who controls my land in the village. However, I know they are from the controlling armed group. I also learned that one of my five shops had been controlled by the brother of one of the officers in charge of the Qastal-A’zaz checkpoint. Additionally, I know that one of my shops has been turned into the facility of the local council in the village. Nevertheless, I have no idea who has seized the apartments and the two shops I have in al-Ashrafiyah in Afrin city.”

Notably, several well-off families lost all their properties after the SNA armed groups controlled their villages. The accounts the partner organizations obtained from IDPs and victims in the Rajo District and the two villages of Bassouta and Kafr Zait corroborate this. The testimonies reflect the impact the confiscations had on the lives of these families, who experienced overwhelming status changes.

One of these families is of a Kurdish IDP from Kafr Zeit village. Using a pseudonym, Dakhil Suleiman listed some of his family’s losses:

“My siblings and I lost nearly 25 hectares of agricultural land, planted with 2,500 olive trees. We also lost a house in Kimar village, along with three villas and 50 hectares in Kafr Zeit village, as well as two apartments in Villat Street in Afrin, a gas station, carwash, and a tire repair shop on the Afrin-Jindires road.”

As for the parties involved in the confiscations, the IDP, who today lives in a village in Aleppo’s northern countryside, said:

“An Arab IDP from Eastern Ghouta lives in my Afrin house. He has rented it from the Eastern Army/Jaysh al-Sharqiya. People whom I do not recognize are investing in the gas station I own on Jindires Road. They named it al-Fursan al-Thalatha (The Three Musketeers). Initially, the station was seized by the Eastern Army/Jaysh al-Sharqiya, which looted all its contents, doors, and windows, sparing only the facility’s frame. As for the rest of our properties in the villages of Kimar and Kafr Zeit, these were confiscated by the Financial Committee of the al-Hamza/al-Hamzat Division and one of the division’s commanders, who housed relatives of his in our homes in the two villages.”

Furthermore, several interviewed Yazidi IDPs, who lost all their properties after armed groups controlled their villages, said that the primary reason many have decided not to return to their homes is fear of arrest and torture.

Torture and Ill-treatment

Field researchers with the partner organizations documented the involvement of SNA armed groups in six torture cases over various intervals during their control of the Afrin region. The victims are a Yazidi old man, a Yazidi woman, a Christian man, and two Muslim men. The armed groups killed two of the victims—one under torture and the other five years after they arrested and released him for demanding his seized property back. The same armed group detained and killed the second victim.

Notably, two cases have been withheld, and only excerpts of the remaining four are inscribed into the report, whereby some details have been concealed out of concern for the security of the survivors or their relatives in the Afrin region.

Tortured and Killed Five Years Later by the Same Faction

The Eastern Army/Jaysh al-Sharqiya tortured Farah al-Din Othman in April 2018. The victim returned to the Afrin region and asked the army to give him back the house they confiscated. The victim’s home is located on 16th Street in Salah al-Din Neighborhood in Jindires.

Five years later, fighters from the Eastern Army/Jaysh al-Sharqiya killed Farah al-Din, his two brothers Nazmi Othman and Muhammad Othman, and his son Muhammad Othman on Nowruz Eve, 20 March 2023.

In May 2023, STJ published an extensive report on the incident, stressing that the killings of four Kurdish relatives are one episode in a series of violations perpetrated against locals in Afrin since its occupation in 2018. Enraged by the killings, the locals organized large-scale protests, holding placards that read, “Five years of injustice are enough.”

STJ contacted a source informed of the torture Farah al-Din suffered in 2018. Using a pseudonym, Radwan Suleiman said:

“After the Turkish military and the SNA armed groups controlled Afrin, Farah al-Din returned to Jindires early and asked the Eastern Army/Jaysh al-Sharqiya to give him back his house in Salah al-Din Neighborhood twice in ten days. However, the army denied his requests. The commander, who met him the second time, accused Farah al-Din of affiliation with the PKK, alleging he used to pay taxes to the AANES. Farah al-Din responded that construction brokers, like him, used to pay the AANES annual taxes. The taxes are divided into three categories [ranging from high to low] based on the broker’s activities. Then the [commander] told him, ‘Leave now, and we will inform you of our decision later.'”

The source added:

“Three days later, fighters from the army asked Farah al-Din to refer to their center. He went there overjoyed, thinking they would return his house. That day, Farah al-Din said a commander sent his fighters, who told him to meet them at the realtor’s office in the neighborhood. The fighters had seized the office. Upon entering the place, Farah al-Din greeted them first, saying, ‘As-salamu alaykum’. The commander responded, ‘Walaikum assalam wa rahmatullahi wa barakatuh, Klshi be Jibtack hatu (hand over all you have in your pockets)’. Farah al-Din handed over the money in his pockets, a pack of cigarettes, and his cell phone. After this, the commander said, ‘Blindfold him and put him on Bisat al-Rih (the torture method known as the flying carpet).'”

The source relayed the details of the torture Farah al-Din suffered at the hands of the fighters:

“Farah al-Din told me that they beat him with a piece of green pipe, often used in household water supply extensions. He also said the Eastern Army/Jaysh al-Sharqiya’s fighters did not interrogate him. They first blindfolded him and drove him around in a car. Following a short round within Jindires, they brought him into the home of one of his neighbors. The house was seized by the Eastern Army/Jaysh al-Sharqiya at the time. They ordered him to take his shirt off and removed the blindfolds. Then they beat him for an hour or so. Due to the extensive beating, his back turned blue and bled. Later, social media [users] circulated photos of Farah al-Din with the marks of torture on his back. In response, the Commander of the Eastern Army/Jaysh al-Sharqiya, Major Hussein Hammadi, nicknamed Abu Ali, visited Farah al-Din. He tried to learn from him how the photos reached Facebook. Farah al-Din responded that he had no idea. They returned his apartment without its contents, which they had looted. The house was furnished. Farah al-Din himself prepared the house and then brought his family in. It was likely an attempt to seize the house by assaulting and horrifying him. However, the fact that information about [Farah’s] torture hit the mainstream and was extensively circulated forced [the army] to give him his home back.”

Photo of Farah al-Din’s bruised back.

The source added that the virality of Farah al-Din’s torture photos horrified the IDP community. He said:

“One effect of the wide circulation of Farah al-Din’s photo on Facebook and the torture marks on his back was that many IDPs in the al-Shahbaa area decided not to return to Afrin. Many IDPs knew that Farah al-Din never had ties with the AANES or the parties, despite which he was beaten and tortured and his house confiscated.”

Repeated Arrests and Torture

The second documented torture case also happened early into the armed group’s control of Afrin. The victim is another Kurdish IDP from a village in the Sharran district’s suburbs. Using a pseudonym, Nizar Muhammad relayed his experience with multiple arrests and torture:

“Several days after Türkiye controlled the Afrin region and [we] fled, I was determined to return to my village in the Sharran district. I was tortured twice on my way to the village. The first time occurred when the Elite Army/Jaysh al-Nukhba-Northern Sector arrested me at Turinde village’s checkpoint. The barrier is located at the entrance to Afrin city, from Bassouta village. I remained held at the checkpoint’s facility for a while, along with 14 other detained civilian returnees. Every detainee was beaten by two fighters from the checkpoint. We were brutally beaten, kicked, and bunched after they placed us one by one at the circle-shaped guard post next to the checkpoint. They tied my hands behind my back with plastic cuffs during torture. We remained like this for hours. The more we moved, the tighter the ties became.”

Nizar, who today lives in a rented house in Rif Dimashq, elaborated on the torture techniques practiced on him:

“They assaulted our honor to humiliate us. They would tell us, ‘You Kurds are separatists and want a State of your own.’ The fighters at the checkpoint also robbed me of 500,000 Syrian Pounds (SYP). They did the same to other detainees. One hour later, they transported us blindfolded. [We were as many as the minibus’s seats]. They took us to Elite Army/Jaysh al-Nukhba’s headquarters in Afrin. There, they subjected us to a strange method of beating. A fighter would hold a portable steel stairway at the center and spin it horizontally like a fan inside a room full of detainees, intending to hit us with every move. The fighters also used pipes. Then, they blindfolded us and tricked us into believing they were going to execute us by shooting their rifles close to our heads. They also hit us with a cable and stepped on our heads. The beating happened in the same room, where they crammed us all. They threatened to kill me if I did not confess. They demanded that I confess to being a sniper with the People’s Protection Units (YPG) and that I killed Turkish soldiers. One [of the fighters] handed me a gun and told me to shoot one of the detainees. I threw the gun away and told him, ‘I do not know how to use it. I never held one in my life.’ They filmed us as they tried to coerce confessions. They would also tell us, ‘Confess, and we will stop beating you’. In fact, they were doing that to hand us over to the Turks.”

Nizar then relayed his experiences at the al-Ra’i prison, where he suffered psychologically due to the dire conditions of detention and where he also turned into an eyewitness to torture exacted on other detainees:

“We were relocated from the Elite Army/Jaysh al-Nukhba’s headquarters to Saraya Afrin [where official departments are] and then to a military post at the Turkish border in Hawar Kilis. We spent a night without food. Then, we were transferred to al-Ra’i prison, where we remained without food for three days. I was not physically tortured or beaten in al-Ra’i prison. However, we drank polluted water. Lice spread in my clothes due to a lack of cleanliness and bathing time. Additionally, using toilets was restricted; we were permitted only two toilet times a day. They would take 10 to 15 detainees to the doorless toilets. The detainees had to relieve themselves quickly in front of the other inmates. I saw detainees laying down on the toilets’ floors due to overcrowding.”

About treatment in detention, he said:

“Once, as he handed food out, one of the prison’s elements addressed the Kurdish detainees, ‘You still want to eat even though we have your honor and land?’ During the interrogation, they took detainees after they blindfolded them. Then they started the torture, ripping their nails off or stinging them with a needle under their nails to force them into making confessions. They often took tortured detainees to solitary detention and returned them to the ward three days later. It was then that we learned about what they had experienced. They also frequently tortured wounded detainees while in the ward. Masked elements enter the room and start interrogating and torturing the detainee. They tortured a YPG fighter who was shot in the knee. Three prison elements beat him with a cable and a pipe, deliberately hitting him on his wound, which was septic. They also threatened to cut off his leg.”

Nizar said torture was not exclusive to men, as the armed groups did not spare women the torment. He narrated:

“We could hear women’s voices in the torture room near our ward. A young man from Kafr Rom village in Afrin’s countryside happened to be with us. His mother was also detained. We learned she was his mother when she identified herself during the interrogation. The young man was shocked and devastated. We thought he was going to die. [His mother] headed the Kafr Rom commune, [the smallest administrative unit within the AANES’s administrative hierarchy]. She screamed at the top of her lungs due to the excruciating pain. They hit her with a cable and electrocuted her. They accused her of forcing children to join the party and tried to coerce her into confessing. We could not sleep due to the shrieks, as torture started at night.”

On the second occasion, when he was tortured by the Sultan Murad Division, Nizar said:

“They stuffed me into a tire—[a torture technique. The detainee is placed within a tire to restrain their movement while extensively beaten]. They hit me on the soles with a green pipe for almost an hour. Three fighters took turns stepping on my shoulder and head while I was on the floor after I reflexively pulled out of the tire. My shoulders have been hurting, and I cannot stretch my two arms backward since then. One of the fighters cussed the Kurds, saying, ‘You Kurds are without honor, and we will *** your honor.”

Nizar said he witnessed four incidents whereby young women, among them minor girls, were forced to marry SNA fighters and commanders despite their families. Two women were returned to their parents only a few days after their so-called “marriage”.

Old Age is Not a Safeguard Against Torture

The third torture case involved a Yazidi IDP who is 73 years old and resides in Aleppo’s northern countryside. Using a pseudonym, Sido Hannan narrated how he was tortured by fighters from the Sultan Murad Division:

“A few days after the armed groups controlled Afrin, my eldest son returned to our village. He died in a bomb explosion as he toured the area. Therefore, his mother and I were forced to return to perform the burial. Nearly a week after we returned, as we were late to leave Afrin, a group from the Sultan Murad arrested me. They led me to a house they seized in Khirbat Sharran village. They blindfolded me and hit me with a cable and the butt of an AK-47 on the soles and back. During the torture, they accused me of belonging to the PKK and repeated that Yazidis are pigs and infidels. They insulted [Yazidis] extensively. I was beaten for three or four days. They also offered to release me in exchange for money. When I reached out to my family, and they promised to pay the money, the beating and torture stopped. I had bruises and poor blood circulation in my back due to the intense beatings with the cable. My left heel was injured, and the flesh in this spot was squashed. The area still aches. After my release, I also developed bronchitis, for which I am still receiving treatment.”

Jindires after the Quake

Jindires district—one of the regions worst hit by the February 2023 quake—was an epicenter for various violations perpetrated by the Turkish-backed armed opposition groups. The abuses accompanied and followed the humanitarian response operations, including the blocking of life-saving aid, discrimination in assistance distribution, seizure or diversion of humanitarian allocations, and confiscation of intact buildings and the rubble of destroyed ones.

As the quake uncovered previous confiscations of civilian homes—where the confiscating parties housed families of fighters or IDPs from elsewhere in Syria—its aftermath revealed a new pattern of property confiscations that emerged amidst the spiking concerns of the local community following Syrian calls for an internationally funded rebuilding in the region. Some locals fear a second round of seizures of their already expropriated properties; others are scared of confiscations that would rob them of the remains of their houses or plots where they stood under the guise of rebuilding or early recovery, which threaten to deny them their property rights permanently.

Notably, several Kurdish survivors in Jindires set up tents across from their crumbling houses and refused to relocate to camps, fearing the loss of what was left of their homes. Their refusal to move into the camps denied them aid dedicated to survivors, who were obliged to stay in makeshift housing established following the tremors to receive assistance.

Using a pseudonym, Samer Muhammad, a Kurdish IDP from the al-Sina’a Neighborhood in Jindires, lost his father and two brothers, in addition to two houses and a shop in the district, after the Turkish military and armed opposition groups controlled the Afrin region in 2018. The forces deployed in the area confiscated his properties, which were later adversely affected by the quake. Samer narrated:

“Relatives and neighbors in the neighborhood told me my apartment’s walls fell in the quake. Due to this, the family that lived there, without informing me, was forced to move out. Later, I learned that they were an Arab family from Homs. However, I have no idea whether they were civilians or related to some fighter. Another Arab family from Homs lived in my parents’ house in the city’s southern neighborhood.”

About his deceased father’s shop, located at the center of the farmer’s market in Jindires, Samer said:

“Before the incursion into Afrin, my brother had rented out our shop at the center of the Jindires marketplace to a civilian resident. The lessee remained in the city after the armed groups took over. However, he refused to pay the rent. Therefore, my brother forced him to leave and then offered the shop to another person. Nevertheless, an armed group later seized the shop and leased it to a different civilian, who later turned it into a butcher shop, where he sold chicken meat.”

Samer expressed his concerns regarding the issue of ownership, fearing his house would be registered under someone else’s name as the owner should properties in the district be subjected to new formal registrations, especially after the catastrophic quake.

Another Kurdish IDP shares Samer’s dilemma. A former resident of Yalanqozê Street in Jindires district, using a pseudonym, Azad Suleiman narrated:

“My apartment, on the first floor, was critically damaged during the earthquake. This forced the family that had seized the house earlier to depart. Before this family, a fighter from Ahrar al-Sharqiya/Free Men of the East resided in the house with his family. Residents from the neighborhood saw him stealing the water tank and several water and electricity installations before he left the house in 2019.”

Azad expressed his concern over the future of his house:

“Over the past years, I sent relatives to check on my apartment several times. However, they were always expelled by that fighter from the Ahrar al-Sharqiya/Free Men of the East who dwelled there first or by the Arab family that lived in the house later. Due to the earthquake, property matters in Jindires are in disarray. I am at a loss as how to protect my apartment from yet another seizure.”

| Notably, multiple violations, including property-related abuses, are attributed to the Ahrar al-Sharqiya/Free Men of the East in the Jindires district. |

Using the pseudonym Darwish Ali, another Kurdish resident of the al-Sina’a neighborhood in Jindires said that the Ahrar al-Sharqiya/Free Men of the East had seized his house for five years before the quake destroyed it. The civilian added that the Liwa Samarkand/Samarkand Brigade had also confiscated an agricultural piece of land with over 800 olive trees in Jindires’s suburbs that he owns with his brothers. Providing additional details on the status of his properties, he added:

“A relative visited my apartment nearly six months after the armed groups controlled the Afrin region. He saw that a security force of the Ahrar al-Sharqiya/Free Men of the East had turned the apartment into a center for their activities. The army fighters tore our pictures off, along with some of our possessions. They also scribbled a phrase on the walls, which indicated the house was seized because the owner was an AANES employee.”

Denied access to his home, Darwish relocated to several areas before he settled down in the Sheikh Maqsoud Neighborhood, west of Aleppo city. He added:

“A while later, the army’s security force left my home. However, the fighters had taken most of my possessions and furniture. Relatives of these fighters, who lived nearby, have even robbed whatever belongings and contents remained in the house. After the quake, my apartment’s building crashed down entirely. Then the Civil Defense removed its rubble, and now nothing is left but the lot where the building stood.”

Darwish’s testimony is one of three accounts the partner organizations obtained from residents within the collapsed building. All four former neighbors are experiencing the same uncertainty about what will happen to the building’s site after the debris is cleared out.

From the same neighborhood, another Kurdish IDP lost his property to rampant seizures. Using a pseudonym, Nihad Ahmad said:

“After we fled the Afrin region to villages in the al-Shahbaa area, I learned that Ahrar al-Sham seized my house and sold its contents, in addition to my tractor and equipment. The commander involved in the seizure contacted me through WhatsApp, trying to justify why he confiscated my home and belongings. He said, ‘We had to pay for the blood of martyrs.'”

The commander is of the mindset trending among the armed groups that control the region. That is, the armed groups have actually “liberated” the area and have offered “martyrs” towards that end, which obliges the locals to pay for the “sacrifice” in return.

Living in Aleppo’s northern countryside, Nihad added that the confiscating armed group had sold his house to another IDP from Homs:

“Later, the armed group sold my two-story house to an Arab IDP from Homs for 4,000 USD. The IDP remains in my house, and I have witnesses who can attest to this.”

Several of the people interviewed for this report shared their experiences with displacement, especially since many had to flee the areas where they stayed three times during the conflict that continues unabating. One of these is a Kurdish IDP who chose the pseudonym Salman Mahmoud. Salman bought a house in the Jindires district after he and his family had to flee the Sheikh Maqsoud neighborhood in Aleppo city following the clashes between the armed opposition groups and the Syrian government forces in 2013. Living in a rented house in Qahtaniyah/Terbasbiyah in al-Hasakah city, he added:

“The Ahrar al-Sharqiya/Freemen of the East seized my house on 15th Street, east of Yalanqozê. The house consists of two rooms and a bathroom, with an area of over 200 m3. I sent a relative of my wife to visit the house. He found a fighter from the army living there with his family. The fighter refused to hand the relative any of our belongings, alleging he would not because the house was a PKK property.”

Five Years of Violations Perpetuate Demographic Change

The context—within which violations and crimes have persisted in Afrin for five years under the rule of Türkiye and the armed opposition groups—retains paramount importance, especially as it offers insights into the drivers as well as the unabating nature of these abuses, which continue despite repeated calls from international rights groups that Türkiye restrains the involved armed groups and cease the violations they are perpetrating against civilians in Afrin.

For a better understanding of the context, this report recalls the beginnings of Türkiye’s effective control of the region, then traces out the ensuing dominance phases, marking out highlight incidents over the past five years, including the February quake, up to the meantime.

This deep review of the region’s recent history attempts to put the ongoing violations in perspective, depending on verified open-source information and visuals, in addition to a massive archive of reports by international and Syrian human rights organizations.

Violations Documented by SNA Fighters

On 20 January 2018, the Turkish military and Syrian armed opposition groups launched Operation Olive Branch, which aimed at controlling the former Kurdish-majority region of Afrin, northwest Syria.

The operation began the day after the Russian Command withdrew their forces at a base in Kafr Janneh. Türkiye treated the retreat as a green light to kick-start the incursion and overlook the brutal assault the Russian military and Syrian government forces initiated against Eastern Ghouta. Ghouta was invaded even though it was covered by the de-escalation zone agreement guaranteed by the Atanas Talks—led by Türkiye, Russia, and Iran. The moves from both sides somehow validate news that claimed there was a Russian-Turkish deal, under which Afrin was handed over to Türkiye in exchange for Eastern Ghouta.

Hours into Türkiye’s control of the Afrin region, on 18 March 2018, various social media accounts and media outlets published reports and footage documenting large-scale SNA-led looting in Afrin and the destruction of the statue of Kawa the Blacksmith—an icon of Kurdish identity and culture—at the Afrin city’s center.

In the aftermath of the extensive media coverage, the SNA and the Syrian Interim Government—both offshoots of the Syrian National Coalition—separately announced they had started investigations into the looting in Afrin. In statements to the media, an SNA spokesperson, Muhammad Hamadin, said the SNA measures led to the arrest of nearly 200 involved individuals, noting that over 90 percent were civilians. On 19 March 2018, Hamadin said, “The acts that have been widely discussed are expected. When any military enters a region, their advance will be accompanied by individual violations by affiliated fighters.”

However, the attempts at minimizing the looting in the city were challenged by the additional videos that surfaced on social media, in which civilians across Afrin and its suburbs narrated how they suffered looting and other violations that occurred during and after armed groups took control of the area.

Several media outlets cited field sources as saying that “the majority of the violations were perpetrated by the Sultan Murad Division, Liwa al-Fath/Conquest Brigade, Ahrar al-Sharqiya/ Free Men of the East, and individual fighters from the al-Hamza/al-Hamzat Division, all of which operate under the flag of the SNA 2nd Legion. Additionally, looting involved sub-groups from the factions affiliated with the SNA 1st and 3rd legions. These forces entered the city on Sunday in large numbers, ranging from 1500 to 3000 fighters.”

Notably, fighters from several SNA armed groups filmed videos of the looting, in which they prided themselves on controlling the city. In an over 8-minute video, which STJ verified, two individuals, likely fighters, ride a motorcycle freely throughout downtown Afrin. During filming, the driver describes the looting of cars, vehicles, and tractors, as well as thefts from exchange offices, clothing stores, and grocery markets, among others, on the streets ahead. In a mocking tone, he declares that everything in the city is now free and that one need only take whatever they find and proceed on their journey. He says, “I swear, everything is for free. Just grab and walk away.”

These audio-video recordings of the violations have given rise to the question of whether the large-scale looting by the fighters has been approved by the commanding power, the Turkish military, or commanders of the SNA-affiliated armed groups at the very least—especially after images of vengeful phrases spray-painted on buildings in Afrin and its countryside were widely circulated.

This line of questioning also relied on former recordings. At the onset of the incursion, fighters published videos documenting thefts in Afrin’s villages that did not even spare birds and other animals, which they treated as “Kurdish spoils of war“. Some of the videos captured the presence of Jihadist militants within the ranks of the Ahrar al-Sharqiya/Free Men of the East, who threatened the Kurds and did not attempt to conceal their Jihadist orientations, praising the heritage of Qaeda in Tora Bora in Afghanistan and that it has reached Afrin.

A second video captured a group of SNA fighters hailing from al-Shuyukh town in Aleppo’s eastern countryside, controlling Shadiya village in the Rajo district. Speaking from the balcony of the village’s mukhtar (governor), one of the group’s leaders is seen threatening to avenge al-Shuyukh‘s town people—allegedly displaced by Kurds. He also promises to reclaim the town, where he will house IDPs from other Syrian regions as guests while his and other fighters’ families settle down in Afrin.

The retaliatory practices documented by fighters themselves and videos that recorded the mutilation of the dead bodies of female Kurdish fighters and summary executions make it even more likely that these violations were systematic and targeted at Kurds on ethnic grounds—especially compared to other instances of Turkish control. When the Turkish military and SNA armed groups controlled Arab or Turkmen-majority areas, such as Jarabulus, al-Bab, and A’zaz, in the context of the 2016 Operation Euphrates Shield, similar large-scale looting operations were not monitored.

Ahead of the incursion, Türkiye sought to bestow a religious character upon the operation through mobilizing Turkish public opinion and extensive promotion, which helped push a narrative that the “Muhammadan” Turkish army and the Muslim SNA armed groups were repelling the infidels in Afrin. On 26 January 2018, six days into the incursion, the president of the Turkish Parliament, İsmail Kahraman, stated that Operation Olive Branch was Jihad fi Sabilillah (Just fight for the sake of Allah).

Several other videos, posted by SNA fighters on their social media accounts, caught the stereotypes that govern their perception of Kurds and their relationship with Islam. By way of test, these fighters asked civilians from Afrin about the number of raka’at (prescribed movements and supplications) in each prayer, regardless of whether those whom they tested were Muslims or Yazidis.

An Archive of Rights Reports

Social media was not the only source that revealed violations perpetrated against civilians during Operation Olive Branch. Numerous reports by international human rights organizations further corroborated the abuses at the onset of the invasion. In a February 2018 report, Human Rights Watch said they “investigated three attacks in Afrin—on January 21, 27, and 28—that killed at least 26 civilians, including 17 children. Among the victims were two displaced families”, adding that the Turkish government did respond to their inquiries regarding the attacks.

In another report, issued in June 2018, Human Rights Watch said, “Türkiye-backed armed groups in the Free Syrian Army (FSA) have seized, looted, and destroyed property of Kurdish civilians in the Afrin district of northern Syria”, adding that “The anti-government armed groups have installed fighters and their families in residents’ homes and destroyed and looted civilian properties without compensating the owners.”

However, the dozens of reports by international and Syrian human rights organizations did not deter the SNA armed groups from committing additional violations against civilians in Afrin as Türkiye disregarded repeated calls for ending these breaches and upholding their responsibility as an occupying power. The behaviors of both the SNA armed groups and Türkiye indicated blatant complicity, which had further manifestations during Operation Peace Spring in 2019. The SNA armed groups that participated in the invasion of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad committed several identical violations against the locals.

In the same context, in an October 2019 report, Amnesty International said they had collected damning evidence on war crimes and other violations committed by the Turkish forces and affiliated armed groups.

However, it later became clear that Türkiye’s role in the documented violations went far beyond ignoring or backing the SNA armed group’s acts. Furthermore, “Ankara consolidated an atmosphere of ‘managed chaos.’ It has established a delicate balance in the security situation that provides it with all the necessary means of control and intervention in the area. This has reinforced persistent fear among the local population in Afrin,” according to a study by Syrian researcher Khayrallah al-Hilu.

The Quake Unleashes Further Concerns

The partner organizations are concerned that rebuilding efforts after the devastating earthquake might be utilized to perpetuate prior demographic changes in the Afrin region. A humanitarian organization declared laying the ground for a new residential village in the Jabal al-Ahlam area, south of the Afrin region, almost 20 days after the tremors, saying it would be allocated to those who survived and were impacted by the recent earthquake that struck northern Syria and southern Türkiye. Qatar Charity also announced the start of the first phase of the Madinat al-Karamah (City of Dignity) project, as part of the rebuilding plan in northern Syria, without indicating the city’s location. However, press reports suggested that the city site would likely be in the Afrin region.

It is worth noting that Kuwait al-Rahma housing village has already been established in the Jabal al-Ahlam in the region of Afrin, which has historically identified as a Syrian Kurdish-majority region. The village is one of the largest human settlements in the region, and 75% of its buildings are allocated to SNA fighters and their families. In a June 2022 investigation, STJ revealed that Rahmi Doğan, governor of the Turkish state of Hatay, is one of the officials responsible for the construction of the housing village. The settlement construction was done with the support of the Rahma International Society and donors from Kuwait, its plans were put in place in early 2021, and it is intended to cover the complete area of Jabal al-Ahlam.

The partner organizations believe that the establishment of such settlements is likely to be a part of a systematic process to alter the demographic makeup of Afrin. The demographic fabric of the Afrin region is evidently changing, especially after IDPs from other Syrian areas were made to settle in the region following the displacement of its predominantly Kurdish population amid widespread suppression of Kurdish culture.

Legal Opinion and Recommendations

From the Perspective of Syrian Legislation

The partner organizations believe it is essential to examine violations and atrocities committed by the SNA, which is under Turkish effective control, using the Syrian Constitution of 2012 and other current Syrian laws. This approach stems from the fact that the forces controlling the areas covered by the report confirm they abide by Syrian legislation, particularly those in effect before 2011.[2]

Perpetrating widespread violations against the inhabitants of the region on the grounds of their dealing with or support for the AANES is contrary to the provisions of Article 51 of the Syrian Constitution, which stresses that there are “no crime and no punishment except by a law”. Additionally, the offense attributed to locals is not established in the Syrian Penal Code, especially No. 148 of 1949.

On the assumption that those armed groups or forces in control of the territory have issued resolutions or laws making these acts offenses punishable by law, those laws must apply to acts or crimes committed after the laws have entered into force and must not have any retroactive effect on previous acts as stated in Article 52 of the Constitution, which stipulates that “Provisions of the laws shall only apply to the date of their commencement and shall not have a retroactive effect, and they may apply otherwise in matters other than criminal.”

This rule is also emphasized in Articles 1 and 6 of the Syrian Penal Code, which takes the defendant’s interests into account. The code provides that the only case in which the new law may be applied to acts committed before its commencement is when its provisions are more favorable to the defendant. Article 3 of the Code states that “any law that changes in a way that benefits the defendant shall be applied to offenses committed before the law entered into force unless a final judgment has already been handed down.” This is underscored in Article 4 of the same code as well.

Additionally, committing such violations against victims or witnesses on the grounds of race or religion, whether as Kurds or Yazidis, is contrary to Article 33 of the Constitution. In its third paragraph, the article affirms that “citizens shall be equal in rights and duties without discrimination among them on grounds of sex, origin, language, religion, or creed.” Moreover, should violations be proven to be geared toward expelling the people from the area and forcing them to migrate, given the cases of some witnesses, these acts would be contrary to Article 38 of the Constitution. The article states that “no citizen may be deported from the country or prevented from returning to it.”

Furthermore, seizing the properties belonging to locals—regardless of motive, whether driven by the purpose of financial gain or demographic change, housing families or affiliates of fighters, or for any other reason—and denying them the chance to invest in and utilize these properties are considered to be contrary to the provisions of Article 15 of the Syrian Constitution, which affirms that private property is inviolable, and Articles 771 and 768 of the Syrian Civil Code No. 84 of 1949. Article 771 stresses that “no one may be deprived of their property except in cases determined by law and in return for fair compensation,” and Article 768 stipulates that “the owner of a thing alone shall be entitled to the use, exploitation, and disposition thereof within the limits of law.”

Moreover, under Article 533, the Syrian Penal Code attributes the charge of homicide to the killings of a segment of the population in the region, including the killings of four civilians on the night of 20 March 2023.

As for the cases of arbitrary detention—often aimed at obtaining a ransom or forcing people to flee the area and leave their property at the disposal of those armed groups—they may be characterized as unlawful deprivation of liberty, as provided for in Article 555 of the Penal Code. Torture is considered an aggravating circumstance when accompanied by the said state of detention under Article 556 of the Code.

Seizures of the victims’ real property are confiscation under duress, as provided for in Article 723 of the Penal Code—since such seizures were carried out by armed groups and at gunpoint, according to some of the victims’ accounts. Additionally, the Code’s Articles 625 and 626 classify looting of the contents of the seized houses as crimes of armed robbery.

Demolitions and vandalism of Yazidi graveyards may fall under Article 467 of the Penal Code, which prescribes “a term of two months to two years’ imprisonment against anyone (a) who violates or desecrates the graves or funeral monuments or intentionally destroys, damages, or defaces these sites; (b) who destroys, damages, defaces, desecrates, or defiles any other objects relevant to the funerary rites or the maintenance or decoration of tombs.”

From the Perspective of International Law

The Rome Statute—establishing the International Criminal Court—defines “persecution”, a crime against humanity, as “the intentional and severe deprivation of fundamental rights contrary to international law by reason of the identity of the group or collectivity,”[3] “on political, racial, national, ethnic, cultural, religious, gender . . . or other grounds that are universally recognized as impermissible under international law.”[4] Even though this report does not claim to draw final conclusions in the judicial sense of this crime, it attempts to provide a legal analysis based on the facts contained therein in light of the definition above.

Notably, the crime of “persecution” covers not only physical and mental harm and violations of individual liberty but also acts aimed at property, for instance, as long as the victims are selected specifically on grounds linked to their belonging to a particular community.[5] “Prosecution” usually results from the commission of a series of interrelated, sequential, or simultaneous acts that may themselves be violations or other crimes, during or after control has been established. These acts include “torture, beatings, and physical and psychological abuse; . . . the establishment and perpetuation of inhumane living conditions in detention facilities; . . . forcible transfer or deportation; . . . seizure of property during arrests, in the context or after acts of forcible transfer or deportation; . . . the appropriation or plunder of property, during and after the take-over, during arrests and detention and in the course of or following acts of deportation or forcible transfer; . . . the wanton destruction of private property including homes and business premises and public property including cultural monuments and sacred sites; . . . the imposition and maintenance of restrictive and discriminatory measures.”[6]

A review of the reported sequence of practices and actions carried out by the opposition’s SNA armed groups, controlled by Türkiye, demonstrates that the acts amount to be systematic and targeted, aimed at the indigenous people of Afarin, namely Kurds and Yazidis. It is remarkable how these acts intersect with those addressed by the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and how they similarly revolve around the severe and deliberate denial of fundamental rights and discrimination against indigenous groups on ethnic, religious, or political grounds. The discrimination intended in these violations manifests in favoritism shown to other non-indigenous populations. These populations are granted privileges resulting from breaching the indigenous community’s rights, such as the seizure of their private property and the direct or indirect prevention of the return of those internally displaced at a time when their property is given to the other population groups, facilitating their settlement.

One notable manifestation of discrimination-motivated violations is the abuses based on working or engaging with the AANES when they ruled the region. It is an established legal principle that a person cannot be held liable for an act that was not illegal at the time it was committed. Additionally, assuming that the new administration of the Afarin region has criminalized dealing with the former AANES, such criminalization remains inapplicable retroactively. In this context, discrimination transpires through the selective application of this charge against individuals and families with the intention of seizing their property or forcing them to pay ransoms and thus uprooting them from the society in which they live. Clearly, such an accusation cannot be leveled against populations that did not reside in the region during AANES’s rule.

Moreover, acts against property as a form of deprivation of fundamental rights under the crime of persecution have received considerable attention in international jurisprudence. The ICTY concluded that the destruction of religious or cultural property/objects was as serious as an attack on a community’s religious identity, which is a clear demonstration of the concept of crimes against humanity.[7]