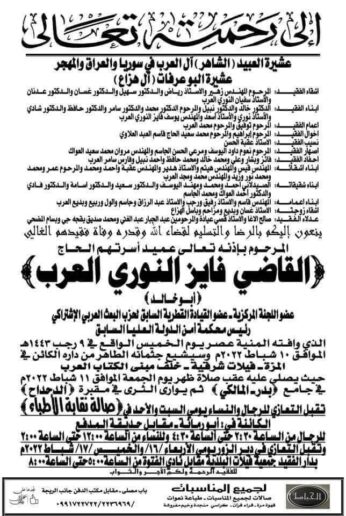

On 10 February 2022, al-Bu Arafat Clan—consisting of Al Haza’ (Haza’ Household), and al-Ubaid clan (al-Shaher)— consisting of Al al-Arab (al-Arab Household), in Syria, Iraq and the diaspora, mourned the death of Fayez al-Nouri al-Arab, known as Abu Khaled, who was one of the Syrian regime’s high-profile figures and pillars of repression. Over the course of his career, al-Nouri served as a member of the Syrian Central Committee of the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party (hereinafter Ba’ath Party) and later as a member of the party’s Regional Command. However, al-Nouri rose to fame after he held the positions of senior judge and head of the notorious former Supreme State Security Court (SSSC). The SSSC sentenced to death hundreds of Syrians who displayed non-conformist political opinions and issued brutal and unjust verdicts against thousands.

Al-Nouri hailed from Deir ez-Zor province, on the Syria-Iraq border, and was appointed senior judge and head of the SSSC in 1979. He remained in office until 21 April 2011, the year that marked the start of the sweeping anti-Syrian government protests and their dissolution, as well as the subsequent substation of the SSSC with the Counter-Terrorism Court (CTC) under Law No. 19.

Al-Nouri earned himself the role of villain in thousands of stories that Syrians continue to narrate, remembering the harsh sentences he leveled against members of the political opposition, depriving them of the chance to defend themselves and putting them to trials that lacked fair proceedings.

While he brought ruin on thousands of lives, the SSSC turned into an archetype of exceptional political courts and a preeminent tool of repression used against the critics of the ruling regime and those who diverged from the doctrine of the Ba’ath Party in Syria.

Rise of the SSSC

The SSSC was established on 28 March 1968 under Legislative Decree No. 47, five years after the Ba’ath Party seized power in Syria through the 8 March 1963 coup d’état. The officers who carried out the coup and fellow Ba’athists celebrate the event as a revolution.

The SSSC was exceptionally created during the presidential term of Nureddin al-Atassi and was used for uprooting the opponents of the Ba’ath Party. Al-Atassi came into office on 25 February 1966 and was ousted in a coup on 16 November 1970. The coup was led by the then Minister of Defense Hafez al-Assad, who claimed power on 22 February 1971.

The Syrian authorities involved in the construction of the SSSC claimed that the court was created for al-Amen al-Qawmi (national security) necessities and to bring under one body all related laws, scattered across several legal frames due to the “war conditions that gripped the Arab countries” following the Naksa (the setback) defeat to Israel in 1967. Therefore, the SSSC brought under its mantle the Emergency Law of 1963, the Decree providing for the construction of National Security Courts issued the same year, and Decree No. 6 of 1965, which provided for the creation of an “exceptional military court.”

The SSSC Jurisdiction

The SSSC’s founding decree of 1986 determined its jurisdiction building on the articles of the General Penal Code, applicable to internal and external security. These articles are the referential sources that laid the foundation for the former exceptional military court established in 1965.

While the SSSC was headquartered in the Syrian capital, Damascus, it exercised its jurisdiction across Syria (Article 1a) by order of the martial law administrator (the President of the Republic). Additionally, the court was authorized to hold sessions anywhere within Syria when necessary (Article 1b). In other words, the court was exempted from adhering to the jurisdiction ratione loci, established by the Syrian Criminal Procedure Code. The jurisdiction ratione loci define the territorial boundaries of a court’s powers, bounding the jurisdiction of each court to a specific geographical area. The jurisdiction ratione loci are part of the public order that gives priority of legal action to courts operative in the geographical location where a crime occurs.

The SSSC was also exempted from applying the general procedural rules encompassed by the Syrian Criminal Procedure Code, which guarantee “the independence and impartiality of judges, multiple levels of appeal, right to defense, public trials, and deeming inadmissible confessions extracted under torturer.” Article 7a of the court’s founding decree explicitly states that:

“With the exception of the right to a defense as inscribed in existing laws, State Security courts are not bound by the procedures stipulated in existing legislation at any point of the investigation, interrogation, and trial.”

The SSSC was a specialized court, presiding over a particular set of crimes, especially those concerning state security. The scope of the SSSC’s concerns is defined by the Syrian Penal Code/External Security, from Article 263 up to article 274, and the Syrian Penal Code/Internal Security, from Article 291 up to Article 311. These articles highlight a diversity of crimes ranging from “treason, espionage, a monopoly on products by merchants and sellers, drastic increases of product prices, and getting cash out of Syria at odds with regulations, to undermining efforts at achieving unity between the Arab countries through holding protests, congregations, or riots, or through inciting a riot, spreading fake news with the aim of creating havoc . . . stirring up sectarian tension, religious or racial strife.”

Moreover, the court brought under its competence practices that are quasi-crimes, including “violating the socialist system of the State, whether the violation was acted out, uttered, written, or committed through any means of expression or publishing.”

Quasi-crimes also include “noncompliance with the orders of the martial law administrator/President of the republic,” “undermining the efforts at achieving unity between the Arab countries, or undermining or obstructing any of the revolution’s goals, whether through holding protests, congregations, and riots, or through inciting riots, or spreading fake news with the aim of creating havoc or shaking the mainstream’s belief in the goals of the revolution.” The court also presides over any cases referred to it by the martial law administrator (Article 5), which means that the court is specialized in looking over the aforementioned crimes, but it is not exclusively bound to these crimes.

Within the frame of these critical exemptions, the successive Syrian governments entitled themselves to prosecute any Syrian individual, civilian or militant, with local or international legal immunity, convicting them based on vague, overbroad terms and provisions that are open to multiple interpretations.

These repressive entitlements are a blatant violation of several principles and rules of fair and just trials, including a breach of the principle that prohibits bringing civilians before exceptional or military courts and other principles that oblige the judiciary to adhere to legal due processes over the course of a trail, applying these rules to all its stages, from interrogation to the verdict and the right to appeal a sentence (right to defense).

Right to Appeal Denied

The SSSC’s verdicts are incontestable. The verdicts are final and cannot be subjected to any appeal methods, ordinary, or exceptional review.

Therefore, the SSSC infringed on the rudiments of the justice principle which stipulates two-tiered litigation. When legal action is carried out in two stages, the case is overseen by Courts of First Instance, Courts of Appeal and finally by the Courts of Cassation. This degradation in the process guarantees good administration of justice and subjects the actions and verdicts of the judge to a higher judicial authority. The stage-based litigation also gives the defendants the right to appeal verdicts or even put them to review. The right to appeal is of paramount importance as it ensures that the judge in the first instance court would not deviate from the principles of justice and the rules of justice and fairness, especially in cases where the verdicts might undermine the rights to life and liberty.

Related to verdicts, the SSSC’s founding decree, Article 9, states that:

“Verdicts made by the Supreme State Security Courts may not be appealed, and verdicts shall not be enforceable except after ratification by the President of the Republic or whoever is authorized to do so (…) The decision of the President of the Republic or his representative is final and is not subject to any method of review and appeal.”

This article bounds the enforceability of the verdict to the decision of the martial law administrator, the president of the republic, a position held by Nureddin al-Atassi, Ahmad Hassan al-Khatib, Hafez al-Assad, and Bashar al-Assad. The verdict is enforced only when ratified by the president, who, in practice, delegates ratification to the deputy martial law administrator, the interior minister.

The delegation is likely a method that presidents opted for to evade direct responsibility for the arbitrary verdicts.

Role of the Martial Law Administrator

The head of state plays various central roles within the SSSC, entitled to ratifying or annulling verdicts, demanding retrial, minimizing the penalty, or substituting it for a less severe one. Regardless of the nature of the decision the president makes, the decision is final and is not subject to procedures of appeal or review (Article 8).

These powers made the president the supreme referential authority for the court, performing both the duties of the courts of appeal and cassation. These shifting roles are also dependent on the president, who decides when to take up these duties.

The president’s domination over the SSSC verdicts, particularly his ability to annul sentences and request retrial is a breach of the provisions of Article 376 of the Syrian Criminal Procedure Code. This role assigned to the president is an infraction of retrial codes because retrial is one of the extraordinary methods of appeal framed by fixed conditions, procedures, and time frames. Moreover, appeal through retrial is designated only to the parties of a case and is not open to nonparties, such as the president. Additionally, Article 8 of the SSSC’s founding decree did not set a specific time frame for requesting a retrial, leaving it open to the decisions of the president, who can refer the case to retrial after a few days or several years following the verdict. In addition to ultimate powers, this article positions the president above all timescales established by judiciary principles and laws.

These unlawful interferences by the president, who is also head of the executive authority, have adverse bearings on the status of the judiciary system. The presidential interventions undermine the national principles of the independence of the judiciary, and the separation of powers, as well as similar international provisions on the issue, including Article 1 of the Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary, endorsed in 1985 by the UN General Assembly resolutions 40/32 and 40/146.

The CTC Preserving the Legacy of the SSSC

On 21 April 2011, one month after the start of the peaceful protests in Syria, President Bashar al-Assad issued Legislative Decree No. 53 by which he abolished the SSSC (Article 1), over 40 years after the court’s establishment. In the decree, the president also ordered that all cases pending before the SSSC and the Public Prosecution therein be referred to the competent judicial authorities in their current state, in accordance with the provisions of the Syrian Criminal Procedure Code (Article 2).

On the same day, the president issued Legislative Decree No. 161, which ended the state of emergency in Syria, established by Resolution No. 2 issued by the National Council for Revolutionary Command on 8 March 1963 (Article One). The state of emergency was thus lifted over 50 years after it was imposed on the Syrian people by the Ba’ath Party.

On 2 July 2012, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad issued the Counter-Terrorism Law No. 19, then followed it up with Law No. 22 of 2012, establishing a special court, the CTC, to look into terrorism cases, based in Damascus. Legal experts identified several points of convergence between the articles of the newly established court and its precedent, the SSSC. For instance, Article 7 of the CTC Founding Law exempts the court from adhering to due process enshrined by the legislation in force, which applies to all stages and procedures of prosecution and trial, except for the right to defense. In other words, the Syrian authorities once again infringed on the defendants’ right to a fair trial by obligating the court overseeing their cases to a set of standards and rules of justice and fairness of fair trials.

In addition to this obvious violation of the right to defense, the CTC has also been scrutinized for sentences in absentia, which do not warrant the subjects to these sentences to appeal verdicts through requesting a retrial, unless the defendant has handed himself/herself voluntarily to the authorities in charge. This provision also breaches the Syrian Criminal Procedure Code. Article 333 of the code states that a sentence in absentia becomes null once the defendant is captured or has surrendered himself/herself of their own accord.

The CTC remains a site for criticism for several other aspects, including the subjects it tackles and the manner of assigning judges. The CTC’s legal frames do not distinguish between adults and juveniles, nor between civilians and militants. Additionally, the CTC, like the SSSC, undermines the principles of the independence of the judiciary and the separation of powers, because its judges are designated by a decree from the president of the republic, including the judges who are supposed to oversee appeals leveled against the CTC’s verdicts.

This convergence confirms that the CTC was established only as a surrogate for the abolished SSSC and to be similarly an exceptional entity outside the established laws.

Conclusion

Both the SSSC, dissolved in 2011, and its offspring the CTC, founded in 2012, functioned at odds with national and international established legal codes, which make their presence a questionable issue. However, their violations of the sanctity of the right to defense remain the core of the controversy, perpetuating injustices against several defendants, who are denied their right to appeal verdicts of the SSSC and later the sentences in absentia of the CTC, unless they are present in person before its judges.

The decisiveness of the two court’s verdicts and the impossibility of appealing them breach the right to defense established in Article 51 of the Syrian Constitution and various international treaties and covenants, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights of 1966, and European Convention on Human Rights of 1950.

The two courts are tools of injustice because these legal breaches deprive the defendants of the opportunity to claim their rights to life and liberty. The neglected right to defense robs defendants of a means to appeal court decisions that might convict them irrevocably, given that appeal is a means through which the legislator grants the defendants a chance to demand reviewing the verdict by investigating the facts of the case, its subject matter, and the legal frames applicable to it.

Appeals remain a necessary tool of justice because judges are humans, who are liable to committing errors, some of which might be fatal, robbing other humans of their life or condemning them to incarceration, sometimes for life. To avoid such life-threatening errors, and accompanying injustices, appeal methods were put in place to enable defendants feeling victimized of objecting to verdicts, by bringing them before a higher-level court from the one that issued the verdict.

Image (1) – A notice from the Ubaid clan mourning the death of Fayez al-Nouri.

1 comment

[…] under the recent amnesty were arrested many years ago and had made appeals before the now dissolved Supreme State Security Court (SSSC), the predecessor of the Counter-Terrorism Court CTC, in accordance with the terrorism-related […]