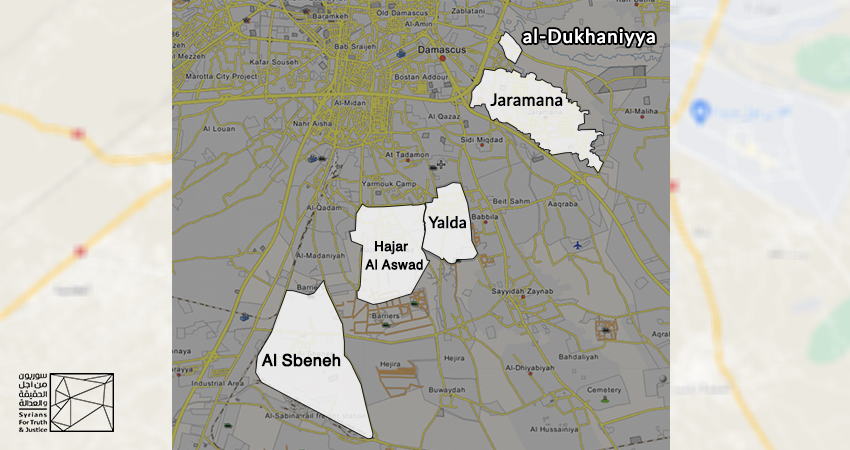

On October 4 2021, the Syrian Arab News Agency (SANA) published a news story about “New urban schemes for Alhajar Al Aswad, Sbeneh, Jaramana and Yalda” stating that Rif Dimashq governate, in coordination with the “firm of engineering studies”, began planning detailed urban schemes for several areas surrounded with “informal housing systems” to make the areas “more harmonious with the biosphere of Damascus city”.

The agency described the targeted areas as “unsound in terms of urban construction and devastatingly destroyed during the crisis”, in reference to the consequences of military operations throughout the years of the Syrian conflict.

The term, urban planning of areas, refers to a set of steps taken by the Ministry of Public Works and Housing to “redevelop the area with new perspective or expand it”, for example, constructing new roads or/ and building new facilities for public services; which, by the end, means bulldozing, confiscating and expropriating big areas of resident’s properties in the name of “urban redevelopment scheming”.

Abdulrazak Dmeriyah, an engineer and head of Regional Decision and Planning Directorate in Rif Dimashq Governate, noted that the decision was taken after a thorough study conducted by the directorate, and that 800 million SYP were allocated for the development of the new urban schemes for the Al Hajar Al Aswad, Jaramana, Ad-Dukhaniyah, Sbeneh and Yalda areas.

Dmeriyah also said that studies are being conducted to annex Ad-Dukhaniyah area to Jaramana city and evaluate the urban plan of both areas to come up with one scheme for both to alleviate population pressure in Jaramana city and confirmed that instructions were circulated to the administrative units whose urban plans are full to submit the required expansion proposals.

While SANA cited an “engineering studies firm”, which most likely refers to the public engineering studies company of the Ministry of Public Works and Housing, as a coordinating and contracting party, it also mentioned, later in the same story, working with a number of specialists and architects from Damascus University who worked on new urban plans in cooperation with the private sector. The inclusion of private individuals in the new projects raises doubts about the intention of Rif Dimashq governate to contract with Emmar Syria Holding Group through urban redevelopment decree 237, which was used to expropriate residents’ properties in the areas of Harasta and Qabun.

On November 27, 2021, Dmeriyah said on Sham FM radio that the new urban plans for Al Hajar Al Aswad, Jaramana, Ad-Dukhaniyah, Sbeneh, and Yalda would be submitted during the first quarter of 2022. After the publication of the new schemes, any citizen would be able to allowed to get a construction license per the urban scheme’s construction guidelines and the procedures outlined in legislative decree No 5, 1982. The announcement tells us that the Syrian Government has defined a new regulating law for the newly targeted areas instead of turning to law no. 10, passed in 2018.

It is obvious that the Syrian Government tends to regulate urban planning of the affected areas in Rif Dimashq, with different laws and legislative decrees. The Syrian Government used decree 237, passed in 2021, to urban plan Harasta and Qaboun, and even though it is not stipulated in the text of the decree, that law no.10 is the regulatory law given the term of “economic stability” stipulated in both. For Al Hajar Al Aswad, Sbeneh, Jaramana and Yalda, Demeriyah confirmed that the legislative decree no. 5, 1982 was the regulating law for the redevelopment plan.

Based on their analysis, legal experts with Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) have concluded that the use of different urban planning laws across the various areas is likely to prevent negative public opinion against the new urban planning schemes and laws. However, while two different laws may be at work, this report demonstrates how they both result in the same consequences for property owners.

What is producing detailed urban plans based on decree no. 5 in 1982?

Decree no. 5, passed in 1982, is known as the “urban planning law” and is listed among a group of urban planning and construction laws.

Usually, urban schemes aim to develop neglected or underdeveloped areas that do not have adequate health and urban conditions, to reconstruct affected areas from natural disasters and wars, or to expand old urban schemes. These plans, which are important to redevelop any area, usually include valuable services the area requires, such as commercial facilities, schools, mosques, churches, and hospitals.

Legislative decree no. 5, first passed in 1982, was updated in 2002 through law no. 41, which provided unified principles regulating the planning of residential areas. These principles established two types of urban plans:

- The Master Urban Plan: a plan that clarifies the future vision of a population center and its expansion by defining the urban boundaries, the network of main roads, the uses of all lands located within its borders, and the construction system for each that do not contradict the main principles of urban planning

- The Detailed Plan: a plan that defines all the details of the network of main roads and secondary streets, pedestrian walkways, public spaces, and all other urban construction details.

According to decree no. 5, the production of urban schemes must pass through a number of administrative stages and complex bureaucracy. The Ministry of Public Works and Housing (executive power) sets the unified procedures regulating the process of planning population centers. Then, the provincial or city council (the administrative unit) sets a planning program following the principles of urban planning.

In other words, the Ministry of Public Works and Housing defines through the urban planning process the province/ area that needs reconstruction or expansion based on the increase in population or the scale of destruction which may have befallen it.

One of the main problems related to the production of urban schemes, per decree no 5, is the lack of a well-defined binding time limit for administrative units (province/ municipal council) to produce the urban plans. Accordingly, the law provides authorities in charge a wide discretionary power for choosing the right time to start planning regardless of the interests of property owners, especially if and when property owners are displaced.

What are the consequences of implementing decree no. 5, 1982 on owners of properties in affected areas?

First, like other urban planning laws, decree no. 5delegates broad unrestricted power to the executive authority represented by the Ministry of Public Works and Housing and the Provincial/ Municipal council in planning a certain area, regardless of the property owners’ interests and needs. Second, the law does not provide clear criteria for area selection, justifying the misuse of laws by executive powers against residents in certain areas.

The misuse of the laws may also be exacerbated by the different circumstances under which the laws are being enacted. When law no.5 was originally passed in 1982, Syria was experiencing a completely different set of circumstances. The law was passed during a time of peace; today, Syria has undergone a decade of destructive armed conflict which has produced new challenges for residents, such as widespread displacement and insecurity. Consequently, the implementation of the decree on Syrians, ignoring the wildly variable circumstances, may have a more negative impact on Syrians today than it did when the law was initially conceived.

One of the issues with decree no.5 which the current circumstances may have exacerbated is the procedure through which property owners are notified of new urban plans. Article 5 (paragraph B) of the law stipulates that the notification shall be either face to face or via publication of the new urban place decision in two local newspapers, across national radio, or TV channels.

Today, most of the residents of the areas included in these new urban plans are currently internally or externally displaced as a result of military operations between the Syrian regular army, the Syrian armed opposition groups, and other armed groups. Their displacement from their homes will make it very difficult for them to learn about the new urban planning announcements via the procedures outline in decree no.5. If they do learn about the new plans, it may be impossible for them to prove their ownership, or even object to the new places, because they live outside of regime-controlled areas.

Furthermore, if residents do want to make an objection to the new decisions, decree no.5 provides only a small window through which to file complaints – 30 days after the initial announcement. This window of time, already short, is made further untenable by the circumstances of displacement. In addition, many of the property owners displaced because of military operations may be liable for persecution by Syrian intelligence forces for their political positions, which will prevent them from being present to contest decisions before the committee referred to in article 5 of the law no 5.

Law no. 5 (article 5, paragraph d) calls for the establishment of a regional technical contest committee formed and presided by the governor, which includes a member of the relevant executive office, head of technical services, head of archeological directorate, road manager in the technical services directorate, two expert engineers specialized in urban planning, one selected by the minister of housing and facilities, and the other by the governor, and a real-estate expert selected by the governor.

The composition of a contest committee explains its functional and administrational subordination to the executive power, where all the committee members are official government staff, who will execute the orders of their superiors with no objection. Originally, the judicial power is responsible for considering contests of ownership rights.

In addition, laws do not stipulate any representation of property owners and affected people to defend the rights of those people in case the committee members abused those rights. Moreover, the law does not impose the existence of a judge or any representative of the judicial power in this committee, which may have created a kind of balance, especially since the committee will likely make partial, unfair decisions against affected people, as most of the members are government staff who are worried only about keeping their positions and satisfying the head of the committee.

Problem/ challenge of power of attorney and security clearance:

In case property owners hear about the new urban scheme and want to prove their ownership, contest the decisions or the scheme itself (even if they are internally displaced or refugees in another country), they will have a problem in making power of attorney for someone – close – to represent them. No articles in law no.5 refer to the possibility of accepting power of attorneys through which property owners can submit contests in the case of their absence.)

The security clearance forms create another challenge for making power of attorneys, which usually take from 3 to 6 months to be admitted (in case the principal of power is not prosecuted or perused by security authorities).

Yet, when property owners have security problems or are sentenced in absentia, the security clearance will be rejected by default, and therefore, they will be deprived of their right to contest or prove their right to ownership.

Suppose for the sake of argument, that the owner gets the security clearance for a power of attorney, the routine procedures and the financial and administrative corruption will take time for getting the power of attorney – certainly longer than the 30-day contesting notice period, making the entire process of contesting useless. It is well-known that the circumstances of war in Syria, which has displaced more than half of Syrians inside and outside the country, will prevent them from appearing before the relevant committee or any other committees.

Problem of interference by the executive power in the works of the judicial power

Urban planning of areas according to law no. 5, 1982 will lead to seizing part of or the entire properties of some owners in areas involved in the plan, as the new plan will lead to the expansion of roads, the creation of new ones, as well as building parks, schools, and other public facilities that all will affect the ownership rights of citizens. Therefore, legally speaking, the Syrian government is supposed to allow affected people to use the court to guarantee their rights. However, the relevant law removes this judicial authority and refers it to a technical committee presided by the governor and membered by a number of his staff to consider contests, if any. Accordingly, the opponent is the judge in the contesting process, forming a kind of abuse of the authorities of the judicial power and a breach of the principle of the separation of powers.

If the Syrian Government has good intentions in conducting projects for the “common good”, fair and tangible compensations should be provided to owners of the properties seized to make this “common good” possible. Yet, law no.5 does not refer to the issue of compensation whatsoever, waiving the Syrian Government from its obligation to compensate affected owners.

Legitimacy of urban plans execution per law no. 5, 1982

Seizing a part or entire properties from owners per law 5. without any compensation contradicts the stipulations of article 15 of the Syrian Constitution currently in force (2012 Constitution), which safeguards private ownership, individual or collective. Under the current Syrian constitution, properties can only be removed for the public interest and if the property owner is provided with compensation equal to the real value of the property. The seizure, which targets some property owners, also contradicts the principle of equality that is emphasized in the preamble of the Syrian Constitution and in articles no. 18, 19 and 33.

Moreover, the seizure also contradicts the stipulations of article 771 of the Syrian Civil Code, issued with the legislative decree no.84, 1948, confirming that no one can be deprived of their property unless when prescribed by the law and with fair compensation.

In addition, assigning consideration of contests of urban plans to the governor’s committee per law no 5/ article 5 will deprive owners from the right to legal remedy stipulated in the Constitution (article 51) because the committee is not a judicial entity but is instead subordinate to executive power.

Above all, seizing properties of some citizens, in the areas involved in the new urban planning, without following the proper legal procedures, or allowing citizens access to adequate contest procedures against the decisions of the administrative unit, and without any tangible and fair compensation, forms a clear contravention to many international charters and conventions that stipulates that everyone has the right to use and enjoy his own property and prohibits arbitrary deprivation of anyone from their properties unless a fair compensation is paid to them.

The European Convention on Human Rights in 1950 states that, “Everyone has the right to respect for his private and family life, his home and correspondence.” Also, The Arab Charter on Human Rights in 2004, confirms that, “Everyone has a guaranteed right to own property, and shall not under any circumstances be arbitrarily or unlawfully divested of all or any part of his property.”

The Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement stresses that, under all circumstances, the property and possessions of internally displaced persons shall be protected against “pillage, direct or indiscriminate attacks or other acts of violence, being used to shield military operations or objectives, being made the object or reprisal, being destroyed or appropriated as a form of collective punishment.” It also emphasized that “property and possessions left behind internally displaced persons should be protected against destruction and arbitrary and illegal appropriation, occupation or use.”