Introduction

The issue of alternative housing in Syria’s capital, Damascus, returned to the front of conversation during a meeting between the Damascus Provincial Council (DPC) and the company implementing the new Basilia City project, near al-Razi.

On 26 June 2002, al-Watan newspaper, which often aligns with the Syrian government, published on its official website a story about a project for alternative housing in Basilia City and the reasons why it has been delayed.

The story noted that a number of DPC members launched a sharp attack on the company implementing the project, the Damascus/Cham Holding, due to their slow development of the project — delays which have severely impacted the civilians who were supposed to benefit from the new housing.

Moreover, several DPC members stated that the General Housing Institution (the executive arm of the DPC that contracted with Damascus/Cham Holding), should be responsible for paying a rent allowance for people who might be affected by the delay.

The DPC members also criticized the delay of the fulfillment of contractual obligations related to maintenance and asphalt for several streets, especially al-Fayhaa Highway. Moreover, the Damascus/ Cham Holding company was accused of failing to monitor the development of the project, for example when contractors failed to complete their work under the pretext of lacking diesel. The newspaper stated that the company justified their failure by the lack of fuel and labor.

Moreover, the head of the DPC, Khaled al-Haraj, emphasized the instructions of the former governor of Damascus (Adel al-Olabi, who was removed from his position on 20 July 2022), regarding the need to address legal violations, commit to Decree 66 of 2012, and to hold those who violate the law accountable (i.e. amending building violations, along with the lack of fuel and labor, led to a delay of the implementation of the project in general and the alternative housing in particular).

Al-Haraj stated that there is no justification for the heads of the service departments who are unaware of the individuals who breached the law, because these departments have cadres and employees who are supposed to carry out their tasks and follow up on filed complaints.

Furthermore, the Director of Technical Studies in Damascus, Muammar Dakkak, confirmed that the General Housing Institution is responsible for alternative housing. He asserted that the DPC should secure the technical files, funds, and sites. Dakkak indicated that there is a slack in the implementation, taking into consideration that several official letters were directed to the General Housing Institution in this regard.

Dakak also explained that 21 sectors of the project are under development. However, with significant delay. Among the obstacles raised, the project’s Supervising Manager, Hisham al-Hamwi, described how the lack of electricity hindered the maintenance process. Additionally, the Supervisor of the Service Complex, Imad al-Ali, noted that service departments failed to obtain the diesel they needed.

Disorganization and disarray have failed to provide Syrians with alternative housing near Damascus, despite the fact that ten years have passed since the beginning of alternative housing projects in al-Razi and al-Mutahlleq al-Janoubi (Southern Ring Road). In failing to provide alternative housing, the DPC has violated Article 25 of Law No. 10 of 2018 (the Article that amended Article 45 in Decree No. 66 of 2012), which obliges the DPC to provide alternative housing within four years of a tenant’s eviction (not of the Decree issuance date, as stated in Article 45 of Decree 66).

STJ published a report on Decree 66 of 2012, which represented the first episode in the property seizure in Syria, and how property owners in the al-Razi area continue to be denied compensation and alternative housing for their properties that the government seized. Moreover, the report discussed how the owners were given an under-valued annual rent compensation, of about 500,000 SYP (the equivalent of 137 USD per year).

STJ believes that the implementing company’s excuses, such as those related to the lack of fuel and labor, led to disorganization and delays during the project’s implementation. At the same time, the DPC failed to fulfill its responsibility for securing alternative housing within four years of the actual eviction.

Since all cases of actual eviction took place between 2013 and 2014, DPC should have secured alternative housing between 2017 and 2018 — before Syria’s severe economic decline and the lack of electricity and labor. Consequently, there is no justification for the failure of the Syrian government.

The decree was likely enforced to enable the Syrian government to seize the properties of the owners who lived in the areas that were known for their military and political opposition to the government in the vicinity of Damascus. The Decree warrants the DPC to invest in the annexed areas “for free”, without clear confiscation criteria, top confiscation ceiling, or censorship.

This prompted the government to issue several decrees and laws such as Legislative Decree No. 66 of 2012, Law No. 10 of 2018, and Legislative Decree No. 237, which framed plans for the construction of “zoned areas” at the Northern entrance of Damascus (Qaboun and Harasta). This was followed by the issuance of similar plans for Alhajar Al Aswad, Sbeneh, Jaramana, and Yalda based on Decree No. 5 of 1982, which is another episode of seizing Syrians’ properties.

The Basilia City Project

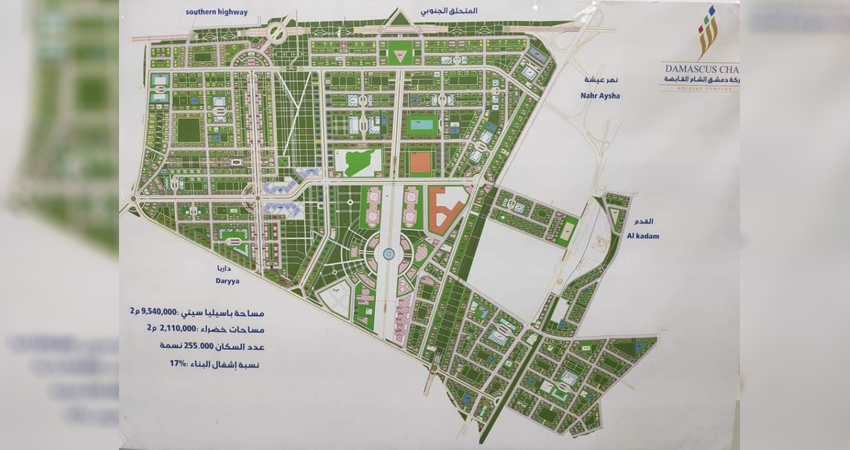

On 19 September 2012, the Legislative Decree No. 66. was issued to frame plans for the construction of “two zoned areas” in Damascus Governorate. The first zone is an area constructed over real estates in Mazzeh and Kafar Sousah neighborhoods. Later, the area was called Marota City. The second zone is an area south of the al-Mutahlleq al-Janoubi (Southern Ring Road), across plots annexed from Mazzeh, Kafar Sousah, Qanawat Basatin, Daraya, and Qadam neighborhoods. Later, the zone was called Basilia City (a Syriac name means paradise). The zoning was justified by the aim of “developing informal and squatter settlements”.

In other words, the DPC and private companies seized properties and paid the owners little compensation. Then, the DPC and their partners sold the properties with exorbitant after-zoning prices to people other than the original owners, including investors.

The Decree provides the Syrian government with legal grounds for relocating the residents of confiscated properties to alternative housing units, the value of which barely amounts to a quarter of the value of their original places of residence. With extensive property appropriations, beyond the limits assigned by Decree No. 66, the DPC is committing a blatant breach of Housing, Land, and Property (HLP) rights, through which it continues to enrich the government at the expense of original property owners.

It is important to note that the DPC annexed 50 sectors within the aforementioned areas for their interest and claimed ownership over them. Later, the Damascus governor transferred the ownership of these sectors, as state-owned shares, to the Damascus/Cham Holding, who established ownership over these shares in return for promises of granting the owners of annexed properties little compensation and alternative housing units.

By not adhering to the responsibilities outlined in Article 45 of Decree 66 of 2012, the DPC misled the Syrian public, especially those affected by the project.

Decree 66 of 2012, amended by Law No. 10 of 2018, obliges the DPC and the implementing company to provide temporary alternative housing, within the same area, to owners who lost their properties because of the project. However, the owners were given a very under-valued rent compensation, which caused them a great loss.

To read the report in full as a PDF, follow this link.