The Damascus-based central Syrian government continues to confiscate and expropriate large plots of agricultural lands in the countryside of Hama province, taking advantage of the absence of their original owners.[1] Many of the property owners whose lands were seized are internally displaced persons (IDPs) who fled their homes due to military hostilities, or expatriates who left the country before the war, or individuals wanted by Syrian security services on alleged “terrorism” charges.

To this date, there have been two large-scale waves of land confiscation in Hama province. The first wave started in mid-2020 after a significant portion of the population fled the extensive military attacks waged by Syrian government forces and their Russian allies against the areas covered by this report. In the aftermath of combat, the government controlled several of the assaulted areas and confiscated vast stretches of agricultural lands. Sometime later, the government-affiliated Hama Security and Military Committee (HSMC) offered the seized lands for rent or investment by public auctions.[2]

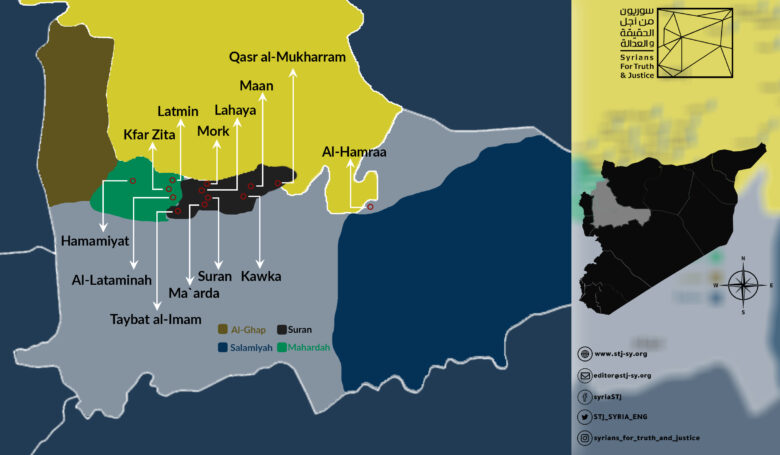

Image 1- A map of where land was confiscated by the Syrian government in the countryside of Hama province. Credit: STJ.

The second wave of land confiscations, which is the subject matter of this report, began in early July 2021. The wave covered plots cultivated with pistachio and olive trees in the towns and villages of Suran, Morek, Latamenah, Kafr Zita, and Lahaya, among others. Like the first wave, the government claimed they expropriated the properties for investment purposes.

This brief report is part of a large effort by the researchers at Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) to document housing, land, and property right violations across Syria.

Previously, STJ published a detailed report documenting land confiscations the Syrian government perpetrated in the provinces of Hama and Idlib and the auctioning dynamics the government utilized to rent or invest in the seized lands. The report revealed that the government seized 60,000 dunums (6000 hectares), wreaking havoc on the lives of the affected farmers.

In this report, STJ records several the new land auctions the government held in targeted areas, drawing on information obtained from witnesses and sources. The interviewed sources confirmed that revenues from auctions and subsequent investments mostly ended with military personalities or militia commanders who are affiliated with the Syrian government, or figures who maintain ties with local government officials.

HSMC Announces Auctions

On 1 July 2021, the HSMC held a meeting and decided to seize agricultural lands that are cultivated with pistachio and olive trees in Hama’s northern countryside. Additionally, the HSMC established sub-committees tasked with surveying the region and the estimated production of the lands lying within the scope of planned confiscations. Furthermore, the HSMC agreed to begin harvesting crops on 20 July 2021. The designated lands were mostly owned by IDPS and expatriates, who traveled and settled abroad before the conflict.

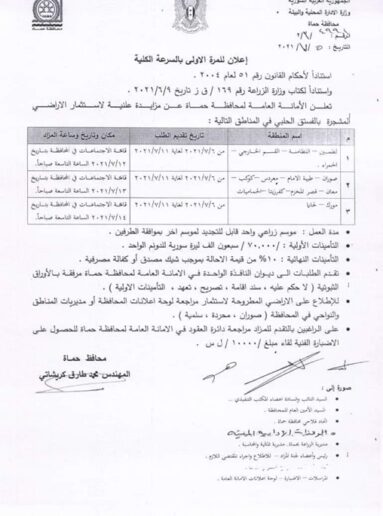

On 5 July, the HSMC published an official auction announcement signed by the Hama province governor, Muhammad Tariq Kraishati. In the announcement, the HSMC offered for investment pistachio and olive groves in Latamenah, Latmeen, al-Hamra, al-Qism al-Khariji, Kafr Zita, Morek, Ma’an, Lahaya, Maardes, Qaser al-Mukharam, Tayyibat al-Imam, Koukab, and Hammamiyat. In addition to the locations of agricultural lands, the announcement included the auction venue—the Hama Provincial Palace—, the dates of submitting investment applications, and investment prerequisites. Investors wishing to bid for the auctioned lands were obliged to pay a deposit of 70,000 Syrian pounds (SYP) per dunum for each season.

Image 2- Copy of the HSMC’s announcement offering confiscated lands for investment by public auction.

On 8 July 2021, the official Facebook account of the Hama Provincial Directorate (HPD) published the details of a meeting that brought together the governor Muhammad Tariq Kraishani, head of the Police Department, Jasim al-Hamad, and the head of the Ba’ath Party office in Hama, Makhzoum Haider. The three officials met at the Hama Provincial Palace to discuss the working methods of the public auctions offering the seized lands for investment.

Auctions Begin

On 10 July 2021, the HPD started the auctions, and investors made bids for investments in the agricultural lands the Syrian government recently seized, mostly from IDPs. On 18 July, the HPD made a statement that the investment auction would continue. The next day, on 19 July, the government’s Minister of Agriculture and Agrarian Reform, Mohammad Qatana, visited the Provincial Palace to check on the progress of the auctions.

Image 3- A picture taken from the HPD official Facebook account of the public auction at the Provincial Palace, during which pistachio fields in Hama’s northern countryside are offered for investment.

To gain insights on the HSMC’s working mechanisms, STJ reached out to an informed source, who attended one of the public auctions. The source narrated:

“The auctions were held to keep up the pretense, because the Select Specialized Committee was intent on choosing specific applicants, who are commanders of militias affiliated with the Syrian government, such as the commanders of the National Defense, Eagles of the Whirlwind, 5th Legion, and other influential figures.”

The source added:

“As for non-military applicants who wish to bid for investments, they must register their names through intermediaries that are members either of the Military Security/Military Intelligence Service or the Political Security Service. Furthermore, they have to pay approximately 300 USD to be allowed to attend the auction— without guarantees that their names will be selected.”

STJ contacted a second source who applied to one of the auctions, hoping to win the chance to invest in his uncle’s land, which the Syrian government had previously seized. The source narrated:

“The applicants had to pay a deposit of 70,000 SYP for each dunum they tendered for. I paid 280,000 SYP at the Directorate of Finance in Hama to participate in an auction that offered my uncle’s piece of land, nearly 40 dunums, for investment. However, the tenders committee granted me only 20 dunums. The remaining dunums the committee gave to an influential figure within pro-government militias.”

The HSMC-led grabs were not limited to IDPs lands. In some cases, the government seized plots belonging to expatriates who left Syria before 2011. To legally facilitate these seizures , the HSMC decisions denied first- and second-degree relatives the right to dispose of the lands owned by people outside the areas controlled by the government, mandating the presence of the original owners—whose names are registered on the title deeds in government records— during any property transactions.

Pertaining to this pattern of seizures, STJ spoke to a farmer from Kafr Zita. The farmer confirmed that the government-affiliated committees seized large plots of lands belonging to expatriates. The farmer recounted:

“In Kafr Zita, the local committee, which is assigned to survey target plots, seized over 300 dunums belonging to a number of expatriates who left the country legally. When these persons demanded that their lands be removed from confiscation lists, the local committee asked them for money in exchange . . . Even if an expatriate’s brother lives in the areas controlled by the government, this would not save the expatriate’s or any other relative’s land from seizure, especially when the expatriate is wanted by government forces. . .The committees seized plots of land owned by IDPS even though their first-degree relatives live in government-held areas. To save these plots, IDPs relatives are forced to apply to the investment auctions to reclaim the land after paying some government-affiliated officer intermediaries to help them be selected while drawing the lots.”

They Rented Their Own Lands

Denied any legal claims over their lands, several the affected farmers resorted to intermediaries or first-and second-degree relatives to act as their agents and give them access to the auctions by which the government offered their seized lands and crops for investment and in which they were themselves denied participation. The farmers were forced to circumvent the government’s unfair measures to protect their lands from loss and to avoid future disputes over ownership rights with strange investors by entrusting the investments to the people they know .

In the section below, STJ offers accounts by two witnesses, who described the violent circumstances that led them to abandon their lands, the subsequent unlawful seizures of these lands by the government, and the actions they took to retain some of their ownership rights.

The first witness, a farmer from Muhradah, painfully narrated to STJ how he fled his home, leaving behind the land which was his and his family’s sole source of income:

“I owned 33 dunums, all cultivated with pistachios. I inherited this piece of land from my father, took care of it and invested lucrative money in it. The land paid off very well. It provided me and my family with a source of income and some capital to run a few small projects. Above all, the crops gave us new hope every year. . . However, the government forces attack on our village forced us to escape our home, especially after my sister died in the shelling. We left our land, hoping we would soon return. However, we ended up in a tent that fails to protect us from cold or heat.”

He added:

“We were forced out of our village before the harvesting season was due, leaving behind crops that cost me over 7000 USD. These crops are now in the hands of local pro-government militias . . . This year, I was hoping to return and work on my land, but I was devastated when the government decided to seize the IDPs lands again . . . I sent a relative to participate in the auction to rent my own land . . . Unfortunately, my relative failed to gain access because we did not bribe government officers government.”

The second witness, a farmer from Latamenah, told STJ about the large sums of money he paid in bribes to rent his own land:

“Government forces cordoned Latamenah in August 2019 to force us to abandon our homes . . . I fled with my family. I could not take the costly agricultural machines I used in the cultivation of pistachio crops over my 26 Dunums (26,000 m2) . . . Our annual land revenues amounted to 30,000 USD. We never imagined that the day would come when we would be deprived of our land, for which we toiled for over 20 years. [Learning about the auctions], we delegated a relative to apply on our behalf. He paid an officer 240,000 SYP in bribes to have his name listed for the bids. Ultimately, we rented our own land for 9 million SYP, not including the deposits.”

____

[1] Ownership rights over targeted lands were transferred to locals on the heels of Agricultural Reclamation Laws enforced in late 1960s, as well as the ownership ceiling laws put in place after Syria and Egypt merged into the United Arab Republic (UAR).

[2] The Hama Security and Military Committee (HSMC) is the supreme political, security and military power in the province. The HSMC was founded after 2011, as the situation in Syria spiraled into armed conflict. Similar security committees operate across provinces that the government controls. In terms of hierarchy, the chain of command goes down from the head of the committee— the highest ranking official— to the governor, the secretary of the province’s Ba’ath Party office, the representative of the National Progressive Front, the attorney general, the head of the police department, the head of the military police department, the head of the Military Security Branch, the head of the General Directorate of Intelligence branch, the head of the Political Security branch, the head of the Air Force Intelligence, the commander of the National Defense militias, and finally command of military brigades and divisions.