1. Executive Summary

In this report, “Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ)” reveals the complicity of three humanitarian organizations, Syrian and international, in the illegal resettlement of fighters of the opposition’s Syrian National Army (SNA) and their families through a project advertised to support internally displaced people (IDPs) in Afrin, which has historically identified as a Syrian Kurdish-majority region.

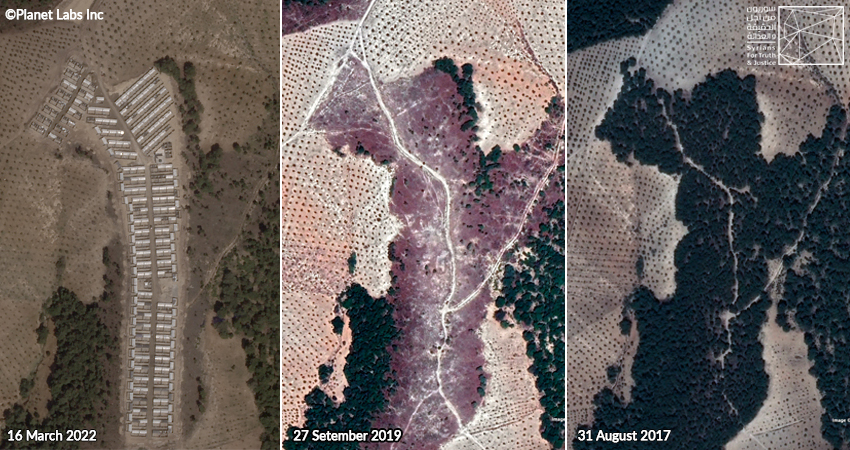

The project was launched by the “Ihsan Relief and Development” organization in “Jindires” district, near “Kafr Safra” town. The project began in 2019 by cutting hundreds of forest trees on a local hillside[1], according to exclusive satellite footage obtained by STJ. The project was implemented on the lands seized in the aftermath of the Operation Olive Branch in 2018, during which thousands of locals were displaced. The “settlement” area is under the direct control of the “Samarkand Brigade” faction of the SNA’s First Corps, supported by Turkey.

Furthermore, STJ learned that “Ihsan” agreed with the faction to permit the organization to build the “village” and facilitate its mission without interference (based on the fact that the faction has an effective control over the area). In return, the faction’s fighters will receive a certain number of housing units. This explains why the organizations involved in the project have given 16% of houses to the fighters of the faction, most of whom are from Idlib, Syria.

In addition to the “Ihsan” organization (a program in the “Syrian Forum“), the “al-Sham Humanitarian Foundation”, under the supervision of the Kuwaiti “Rahma International Society” organization, participated in serving a part of the project and encouraging IDPs from other Syrian regions to settle in that village.

These two organizations played a key role in building Jabal al-Ahlam (Mountain of Dreams), most of which was devoted to housing fighters and their families, which is an example of forced demographic change which has occurred throughout the Syrian conflict.

The village that was established by the “Ihsan” organization consists of two residential blocks (an eastern and a western block). It is one of nine villages and human settlements, whose construction work began after the Turkish military occupation of the Afrin region, according to the description of Amnesty International[2], which documented different patterns of violations after the occupation[3]. The Syrian Justice and Accountability Center (SJAC), also concluded that because Turkey exercises effective control over parts of northern Syria, including both exercising military control and enforcing Turkish laws, running schools, and organizing other institutions, it has obligations as an occupying power under the Fourth Geneva Convention.

According to reliable sources of STJ, all of these illegal villages were built upon the approval of the Afrin City Local Council (ACLC) and based on the instructions of Rahmi Doğan, governor of the Turkish State of Hatay, and the Turkish official responsible for this area.

2. The Geographical Location of the “Ihsan” Project

The village, referred to by some local sources as the Village of Hope, is located in forested land at the foot of a hill northeast of Kafr Safra town, in the district of Jindires. The site is known locally as “Jiai Shauti”. The land is owned by the Syrian State and not a sole proprietorship.

Currently, the area is under the authority of the Samarkand Brigade faction of the 121st Brigade. The latter is affiliated with the 13th Division in the First Corps of the Ministry of Defense of the Syrian Interim Government affiliated with the Syrian Opposition Coalition.

Satellite footage shows that the hillside was previously covered with forest trees which were cut down in the area on which the residential village was built. As for the rest of the hill and the lands surrounding the project, forests remained as before. This indicates that tree cutting was deliberate and came with the aim of building this village.

According to the testimony of a worker in the same project (the first source), the organization implementing the project, “Ihsan for Relief and Development“, cut down and distributed trees to a number of families benefiting from its relief programs in the region. The source recounted:

“The organization cut down trees at the construction site and its surroundings on the pretext that trees hinder construction work, impede heavy machinery and hamper paving the road that leads to the hill. The number of felled trees was not very large. Those trees were cut and distributed to the beneficiaries by the organization. The latter did not sell or trade trees”.

Image (1) – Satellite footage shows the location of the village before and after felling trees

3. Details and Goals of the Project

The announced goal of the project is to build 247 permanent housing for the IDPs who are forcibly displaced from various Syrian governorates. Construction work started in May 2020. However, the process of cutting down trees and preparing the land took place in 2019.

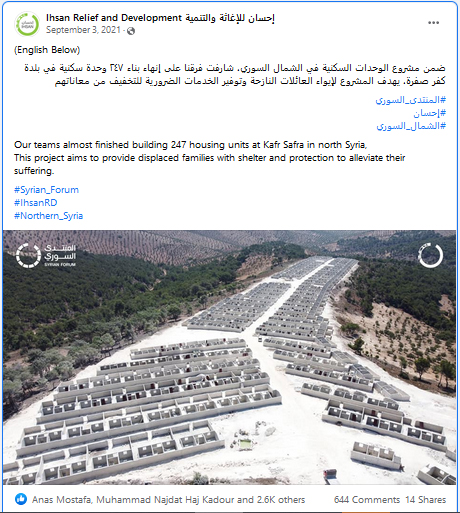

In September 2021, Ihsan announced via its official page on Facebook the near completion of the construction work of 247 housing units/houses. Some families have already moved from Aleppo and Idlib to live in the village, as per the photos published by North Press, which reflects the presence of some families in a part of the village. Nevertheless, construction work is still ongoing in another part, as of the date of finishing this report by the end of May 2022.

In August 2022, STJ learned, from a civilian, that housing operations have already begun and more than half of the people for whom housing was allocated have been accommodated.

Image (2) – a screenshot of a Facebook post published by “Ihsan” organization, announces the near completion of building 247 housing units in Kafr Safra.

Image (2) – a screenshot of a Facebook post published by “Ihsan” organization, announces the near completion of building 247 housing units in Kafr Safra.

According to a worker in the project (the first source), the area of the village ranges between 40 to 50 acres, equivalent to 40,000 – 50,000 m2 approximately. It includes a school, a nursery, a mosque, an institute for memorizing the Qur’an, a clinic, small gardens, and several shops, as well as a water well and paving and gravel roads.

STJ’s second source, an administrative officer in the project, stated that the implementing agency, Ihsan, selected the beneficiary families, and 60 of them are already settled in. The source indicated that most of the registered families are civilian IDPs. Nevertheless, at least 40 houses are allocated to the fighters of the “Samarkand Brigade” faction which controls the area. The source recounted:

“The families that were selected by Ihsan organization, registered for this housing beforehand. The selection was based on families’ needs. As an alternative to cash, certainly 35 to 40 houses were allocated to the faction in control as per the latter’s demand. These houses were handed over to the faction, which distributed them to its fighters and their families. Also, it is possible to find that some members of beneficiary families are fighters in different factions as well. Nonetheless, the largest percentage of the beneficiaries is civilians”.

The source continued:

“A dispute had previously occurred between Samarkand Brigade and the project contractor [Khaled Salama], due to the latter’s refusal to pave the road that leads to the village and other sub-roads. The dispute caused a six-month delay in the delivery of the project. Finally, they agreed to lay the road with gravel instead of asphalt to avoid the high cost”.

STJ’s third source, an employee of Ihsan and a beneficiary of the project, narrated:

“Selected building materials are durable, such as iron, cement and bricks/blocks, because the project will serve as permanent housing for beneficiaries”.

The fourth source, a displaced civilian and project beneficiary[4], said in an exclusive testimony to STJ during the month of August 2022 about the role played by the Samarkand Brigade in the project.

“The man responsible for the housing settlement’s security is a member of the Samarkand Brigade named [Y. Al-Nazim], which perhaps explains why the faction’s fighters have acquired a large percentage of the housing, as well as explains their interference in civilian affairs by conducting ‘security investigations’ about them.”

The source also added that the man responsible for the “settlement’s security” controls the settlement’s residents and bestows decisions and warnings to them, and that civilians have been negatively affected by the faction’s control over the settlement, such as the deprivation of humanitarian aid. He added:

“A while ago, the Samarkand Brigade suddenly evicted three families in the middle of the night. No one was allowed to protest. In fact, the faction most dominant in the settlement is the Samarkand Brigade, and neither the civil or military police, nor the local council, can interfere in the affairs of the residential settlement because it falls under the Samarkand Brigade’s control.”

4. What is the Samarkand Brigade Faction?

The Samarkand Brigade (attributed to one of the Uzbek cities in Central Asia) was formed by Wael Mousa in June 2016. Wael was killed during Operation Olive Branch in 2018. Afterwards, Thaer Marouf took over the leadership of the faction. The faction’s fighters are originally from al-Zawiya Mountain in Idlib. Now, the faction is stationed in multiple points in Jindires district. Other opposition factions are also present in Jindires, including the Levant Front/al-Jabha al-Shamiya, the Ninth Division, and Eastern Army/Jaysh al-Sharqiya.

According to inside sources, fighters receive their monthly salaries of about 600 Turkish liras from the Turkish government.

The Samarkand Brigade participated in the “Olive Branch” and “Peace Spring” operations, and sent dozens of its fighters (including children) as mercenaries, to both Libya and Azerbaijan. The United Nations had verified the recruitment and use of three children in Libya by Syrian armed opposition groups (formerly known as the Free Syrian Army). Children were smuggled from Syria to Libya by al-Mutasim Division and the Samarkand Brigade. This was addressed in the report submitted in May 2021 by the Secretary-General of the United Nations to the Security Council on the issue of children and armed conflict.

The faction had previously committed numerous violations against the people of Jindires district, such as cutting down thousands of trees, arbitrary detention, financial extortion, and the seizure of property, as well as plundering civilian property (particularly in the early days of their control). Furthermore, they have taken over several olive presses owned by the people of the region.

(Image 3) – The Samarkand Brigade’s Logo.

(Image 3) – The Samarkand Brigade’s Logo.

5. The Role of Afrin City Local Council (ACLC)

The Afrin City Local Council (ACLC) played a prominent and fundamental role in giving Ihsan the land on which the project was built and providing a license to build on agricultural lands in Jindires. This took place prior to the organization’s agreement with the Samarkand Brigade.

The ACLC’s role was made up of two parts. First, an organizational role between the Ihsan organization and the office of the Turkish governor, which issued the initial approval of the project to the representative of the organization. Later, according to STJ’s sources, the governor’s office gave oral orders to ACLC to facilitate the work of Ihsan. Subsequently, ACLC proposed several places where the residential complex could be built. ACLC will later grant the organization an allocation paper for the whole project upon its completion. The organization shall deliver a sub-allocation paper for one quota to all beneficiaries.

In addition to playing an organization role, the ACLC plays a coordinating role between the Ihsan organization and the Jindires City Local Council (JCLC). The reporting comes from ACLC to JCLC, with the approval of the Turkish governor. This case is very similar to the license that ACLC provided to organizations that built the settlement of Jabal al-Ahlam (Mountain of Dreams).

According to STJ’s sources, it was remarkable that unlike ACLC, JCLC did not make a direct decision on the project.

6. How is the Region of Afrin Governed?

All of Afrin’s seven districts are under the authority of the office of Rahmi Dogan, the governor of the Turkish State of Hatay, who is assisted by a group of deputies who each oversee a district in Afrin. STJ learned this information from several members of local councils. They confirmed that the residential unit in particular is under the jurisdiction of the deputy governor of Hatay, who is responsible for Afrin district.

As for the general work mechanism of local councils, STJ’s sources have summarized it as follows:

“In terms of administrative subordination, local councils follow the opposition’s Syrian Interim Government. However, practically they receive most of their orders from the Turkish deputies of the governor. They supervise development and economic plans, in addition to expenditures. Salaries and financial allowances of councils’ employees are paid monthly from Turkey as financial grants provided by the governor of Hatay. Some of these monthly payments are provided by Qatar through the Turkish government, while some are deducted from taxes and fees revenues”.

STJ’s fifth source, another employee of Ihsan and a beneficiary of the project, told STJ that:

“The establishment of the residential village was authorized by ACLC, after the organization obtained the building license. ACLC has also approved the selection of this land since it was a common property, and the organization will not pay for it. However, the people of Kafr Safra disagreed, claiming they have a right to the land”.[5]

The source added:

“ACLC gave the organization a collective license for all the housing units that will be built. Further, the organization received promises from the council to give the beneficiaries a proof of ownership [like what is called a ‘Green Tabo’ paper].”

STJ’s team reviewed the official accounts of ACLC and JCLC but did not find any publication or announcement related to the residential village that is being built in Jindires, unlike other housing projects such as Basma Village and Kuwait al-Rahma village that were announced and celebrated by the council.

7. Relief Organizations Involved

- The Ihsan Relief and Development organization is a program in the Syrian Forum. The Syrian Forum defines itself on its official website as a non-profit organization, registered in Turkey, with partnerships in Austria and the United States of America (USA). The forum was established in 2011 and contains five programs. By the end of 2020, the number of its staff members was 2,318. The Syrian Forum along with its partners have 17 offices in Syria, Turkey, Austria, USA and Qatar. Ihsan is one of the five programs. Moreover, the project of Kafr Safra village, implemented by Ihsan, is addressed in the Forum’s annual report 2021 (pages 26-27).

- The al-Sham Humanitarian Foundation was licensed in Turkey in 2014, under the name (Sham al-Khair Foundation), registration number (073/030/01). Today it has five offices in Syria that contribute to all sectors of charitable work. The foundation contributed to this project by building a mosque and an educational center, under the name of Ayad Askar Al-Anzi (a Kuwaiti donor), which went into operation in October 2021. The area of the mosque is around 130 m2, fully equipped, and can accommodate 200 people. It includes a minaret, a dome, and public facilities. On the other hand, the educational center is around 80 m2, equipped with all educational equipment, and accommodates 150 male and female students. It consists of 3 classrooms, an administration office, and 2 bathrooms. This work on “Ayad Al-Anzi” is under the supervision of the Rahma International Society, which has been publicized by Ministry of Social Affairs under ministerial resolution number (100/A 2018 AD), to offer its services to the needy inside and outside the State of Kuwait, through developmental, educational and health projects intended to boost human life in addition to orphan, poor and humble families and providing urgent relief for the people in need.

3 image addon required to activate 3 image slider

Image (4) – Satellite footage shows the residential complex in Jindires.

8. The Aforementioned Actions in the Perspective of the Syrian Law

The actions carried out by the Samarkand Brigade in cooperation with ACLC and the aforenamed organizations constitute an offense. Article 724 of the General Penal Code (No.148 of 1949) levels a prison sentence of up to six months against anyone who usurps a portion of state-owned properties.

Moreover, The Legislative Decree for Removal of Building Violations (No.40 of 2012) imposes a penalty of imprisonment from 3 to 12 months for anyone who is proven responsible for building violations. This includes owners of the building, possessors, occupants, contractors, implementers, supervisors, and anyone who examined the building. This applies when the building in violation is located (even partially) on public property, property of the state, or property of the administrative unit. Accordingly, in Jindires case, whoever supervised, implemented, examined, or prepared the building plans, is involved in committing a crime, and therefore could be punished under the law. Illegally built structures must be demolished at the violator’s expense, with a fine of 2,000 to 10,000 Syrian Pounds (SYP) per square meter on whoever is proven responsible for the violation (Article 2).

Parties addressed in this report cut down hundreds of forest trees in preparation for the implementation of the project. This act breaches the Forestry Law (No.6 of 2018), Article 32, which imposes a penalty of imprisonment from 6 months to 2 years, and a fine that ranges between 500,000 and 1,000,000 SYP, on anyone, without prior authorization, uproots, cuts, damages or distorts trees and shrubs in the State forests, or performs any act that leads to their destruction.

Consequently, ACLC violated the Forestry Law by providing the Ihsan organization with a collective license for all the housing units, as well as by promising to give the beneficiaries a proof of ownership (as per STJ’s source). Based on Article 39, offenders could be sentenced to 3 to 5 years in prison and pay a fine ranging between 100,000 and 200,000 SYP.

Furthermore, the practices of the local councils were carried out in violation of the Syrian laws in force. The Syrian Civil Code No. 84 of 1949 grants the person who initiates construction work on or cultivates the property of others the “right to property acquisition by accession”, provided that the building or cultivation is worth greater than the value of the property on which construction work was initiated, and also provided that the person involved is carrying out the construction work or the cultivation in good faith “bona fide” (they believe they own the property when those actions were pursued). Pertaining to the case under study, STJ believes that all those who were allocated properties do not meet the good faith condition, since they are people displaced from various areas throughout Syria, including Homs and Rif Dimashq, among others. Because they come from different areas, the recipients of these plots certainly know that the properties they were allocated do not belong to them, nor to the local council that granted them the allocation papers.

Most importantly, “the right to acquisition by accession” does not apply to properties registered in the Cadaster, or those owned by the State. Therefore, none of the persons allocated properties may claim any right to the real estate given to them, regardless of the time they possessed or occupied the property (Articles 925 and 926 Civil Code).

9. Conclusions in the Light of the International Law

It is established in international laws and practices that organizations working in humanitarian fields have a duty to abide by four guiding principles: neutrality, impartiality, humanity, and independence.[6] Neutrality means that humanitarian aid must not favor any side in an armed conflict or other dispute. Impartiality states that humanitarian aid must be provided solely based on need, without discrimination based on nationality, race, religion, social class, affiliation, political opinion, or other objectives. Humanity demands that the primary motive for humanitarian actions should be to respond to human suffering wherever it is found and regardless of who suffers from it. Independence is the autonomy of humanitarian objectives from the political, economic, military, or other objectives that any actor may hold regarding areas where humanitarian action is being implemented.

Furthermore, International Humanitarian Law (IHL) imposes providing medical relief according to the priority of need, with no distinction between civilians or combatants, or based on affiliation to a certain party to the conflict.[7] The principle of neutrality requires that a distinction must be made between combatants and civilians, and the utmost must be done to ensure that the needs of the civilian population are adequately met.[8]

Humanitarian organizations must prevent the parties to a conflict from directly or indirectly appropriating aid intended for the civilian population.

Based on the duty of parties to conflict to facilitate rapid and unimpeded passage of humanitarian relief for civilians in need, IHL has permitted humanitarian actors to negotiate with these parties, particularly those controlling areas of transit and distribution of consignments.[9] Moreover, parties to a conflict cannot achieve material or military gains, nor recognize a particular legal status, since this could amount to a violation of the overall principles of a humanitarian action.

Accordingly, the agreement between the concerned organizations and the Samarkand Brigade to possess around 16% of the houses allocated to civilians and victims of conflict,[10] is a breach of humanitarian principles. It prejudices the right of civilians to obtain humanitarian relief, and the duty of the parties to facilitate access. If humanitarian relief contributes directly or indirectly in strengthening the power of one party to the conflict, this could lead other parties to reconsider their consent to aid distribution.[11] Consequently, civilians -all over the country- might be affected by this precedent, since aid that does not meet the conditions of neutrality and impartiality will most likely not be considered humanitarian.

On the other hand, there is a solid link between impartiality and non-discrimination, especially that both principles require proportionality in terms of response based on level of need.[12] Since the mentioned organizations provide services in a specific area, and have access to everyone without any interference, then they have an obligation to respond to civilian needs transparently and based on an objective assessment. Thus, organizations should not rely on a subjective assessment, based on ambiguous selection mechanisms, controlled by any party to the conflict.

Activities of relief organizations addressed in the report are linked to a context in which a series of possible violations are committed against the indigenous population. This could particularly be noticed in the enforced displacement of indigenous people and the consolidation of the presence of a new population. Therefore, directing the services of these organizations for the benefit of the new population exclusively, and excluding indigenous people as well as denying their humanitarian needs, may amount to a participation (directly or indirectly) in these potential abuses.

The State -Syria in this case- has a duty not to refuse the passage and access of humanitarian aid in cases where the lack of relief may lead to starvation of the civilian population.[13] In this context, the Institute of International Law has clarified that “Affected States are under the obligation not arbitrarily and unjustifiably to reject a bona fide offer exclusively intended to provide humanitarian assistance or to refuse access to the victims. In particular, they may not reject an offer nor refuse access if such refusal is likely to endanger the fundamental human rights of the victims or would amount to a violation of the ban on starvation of civilians as a method of warfare”.[14]

Accordingly, this restriction imposed on a State does not give humanitarian actors absolute freedom to implement numerous programs and interventions simply because they are classified as “humanitarian”, particularly since these actors have a duty to respect the local law -regarding entry to the State’s territory- as well as to consider applicable security requirements.[15]

According to the interventions observed in this report, and in comparison, with the potential breaches and violations of national and international laws, the provision of “humanitarian assistance” could be used to escape condemnation as an intervention in the internal affairs of the State, as concluded by the International Court of Justice in 1986.[16]

All the above leads to a direct or indirect contribution to providing support for an armed non-state actor party to the conflict. Therefore, we need to analyze the particular legal responsibilities and potential violations.

As an occupying power, Turkey bears legal responsibility for relief and humanitarian activities in territories under its control, as it has become established in international forums,[17] and in accordance with Turkey’s obligations in international law.[18] According to the information addressed in this report, particularly in terms of official mechanisms adopted by relief organizations to obtain official legal and procedural licenses, it is clear that Turkey -in theory- adheres to Article 59(1) of the Geneva Convention (IV) regarding the facilitation of relief activities. This could be noticed in the oral approval of the Turkish governor, which formed the cornerstone to local councils that issued necessary approvals and/or licenses to the organizations listed in this report, to implement the project. However, this theoretical fulfillment of legal duty is void of its humanitarian goal; Turkey, as an occupying power, and according to the data provided in the report, did not perform due diligence to ensure that aid and/or services achieves its humanitarian purpose, at odds of Article 60 of the Geneva Convention (IV), which forms the cornerstone for the State to agree on the entry and distribution of humanitarian aid through/to its territory, in accordance with Article 23 of the Geneva Convention (IV). Perhaps the last condition mentioned in this Article -restricting the right of passage of consignments in which a specific advantage to the “enemy” can be achieved- is the most important in terms of the obligations of the occupying power, and the organizations that carry out humanitarian aid missions either by offering their services or assigning them to the authority in question.

The fact that fighters in the “Samarkand Brigade” benefit from buildings designed to respond to civilian needs, is clear evidence of a specific advantage of a party to the conflict. In this context, the responsibility of the occupying power is multiplied as it exercises comprehensive control over the “Samarkand Brigade” and other factions, which causes relief consignments to be diverted for the benefit of the occupying power and its proxies. These consignments must be retained wholly and exclusively for the population of the occupied territories.

On the other hand, there is a responsibility on the organizations working directly or indirectly on this project. In addition to the above-mentioned potential violations committed by the organization leading the project, donors bear legal responsibility for violations committed against the State and civilians who are supposed to be the only beneficiaries of these humanitarian actions. Donors should adhere to the requirements of due diligence before providing grants, particularly with regard to final beneficiaries; their background and practices in the light of international law.

[1] The hill is known locally as “Kafr Safra hill”.

[2] See e.g., Human Rights Council, Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic, 14 August 2020, A/HRC/45/31, § 67; Human Rights Council, Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic, 11 March 2021, A/HRC/46/55, § 94; and Human Rights Council, Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic, 08 February 2022, A/HRC/49/77, § 93.

[3] Human Rights Council, Human rights abuses and international humanitarian law violations in the Syrian Arab Republic, 21 July 2016- 28 February 2017, Conference room paper of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic, 10 March 2017, A/HRC/34/CRP.3, § 103.

[4] The witness requested anonymity in order to testify. The interview was conducted in early August 2022.

[5] Since it is a common land in their village, people believe they are the ones who deserve to benefit from it.

[6]See UN General Assembly Resolutions 46/182 in 1991 and 58/114 in 2004.

[7] ICRC, IHL Database, Rule 88. Non-Discrimination. Available at: (https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/customary-ihl/eng/docs/v1_rul_rule88)

ICRC, IHL Database, Rule 110. Treatment and Care of the Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked. Available at:

(https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/customary-ihl/eng/docs/v1_rul_rule110)

[8] Ruth Abril Stoffels, Legal regulation of humanitarian assistance in armed conflict: Achievements and gaps, IRRC September 2004, Vol. 86, No. 855, 515-546, p. 542.

[9] A rule of customary IHL. See ICRC, IHL Database, Rule 55. Access for Humanitarian Relief to Civilians in Need. Available at: (https://ihl-databases.icrc.org/customary-ihl/eng/docs/v1_rul_rule55).

[10] See ICJ, Case concerning Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v. United States of America), Merits, Judgment, 27 June 1986, ICJ Reports 1986, para. 242.

[11] ICRC, Commentary on Convention IV relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, Commentary of 1958, p. 322. See also Article 23 of Geneva Convention (IV).

[12] ICRC, Commentary on Convention IV relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, Commentary of 1958, p. 97.

[13] A rule of customary IHL. See ICRC, IHL Database, Rule 55. Access for Humanitarian Relief to Civilians in Need.

It is also a reflection of Article 18(2) of Additional Protocol II and Article 70(1) of Additional Protocol I.

[14] Institute of International Law, Resolution of the Institute of International Law on Humanitarian Assistance, Bruges Session 2003, Art. VIII.1. Available at: (https://www.ifrc.org/Docs/idrl/I318EN.pdf)

[15]Additional Protocol I, Article 71(4).

[16] ICJ, Case concerning Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (Nicaragua v. United States of America), Merits, Judgment, 27 June 1986, ICJ Reports 1986, para. 243. Available at: (https://www.icj-cij.org/public/files/case-related/70/070-19860627-JUD-01-00-EN.pdf)

[17] See e.g., UN General Assembly, Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic, 14 August 2020, A/HRC/45/31, § 67 (Available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G20/210/90/PDF/G2021090.pdf?OpenElement); UN General Assembly, Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic, 08 February 2022, A/HRC/49/77, § 93 (Available at: https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G22/251/52/PDF/G2225152.pdf?OpenElement); and UN News, UN rights chief calls for Turkey to probe violations in northern Syria, 18 September 2020 (Available at: https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/09/1072752).

[18] Geneva Convention (IV), Article 55(1); and Additional Protocol I, Article 69(1).