Preface: According to many testimonies Syrians for Truth and Justice/STJ obtained in January 2018, Autonomous Administration in northern Syria continued detaining many young men within its areas, with a view to recruit them under the self- defense duty term proclaimed on July 21, 2014, as many young people were pulled directly to the Autonomous-Administration recruitment camps, although they excluded from the military service for various reasons, including postponement for studying.

Parallel with the operation launched[1] by the Syrian Democratic Forces/SDF to expel ISIS militants from Deir ez-Zur and Raqqa provinces, Autonomous-Administration agents arrested more youths in al-Hasakeh and not only that, but even some of the employees in the education field were arrested and forcibly recruited, although they have an official paper allows them to postpone their service, that was according to a STJ reporter.

First: Autonomous-Administration Formation and Promulgation of Mandatory Law of Self-Defense Duty

On January 21, 2014, Democratic Union Party/PYD and the allied Kurdish, Arab and Syriac parties formed Autonomous Administration in northern Syria; as a result the following three provinces were formed and named "cantons":

1. Canton Jazira.

2. Canton Kobani.

3. Canton Afrin.

Each province forms its own councils, which are the General Councils

Autonomous Administration comprises 16 bodies, namely, the Municipalities and Environmental Authority, Foreigner Relations Authority, Self- defense Authority, Legal Affair Authority , Martyrs ' Affairs Authority, Women Committee, Culture and Art Authority, Tourism and Antiquities Protection Authority, the Education Authority, Finance and Economics Authority, Labor Authority, Social Affairs Authority, Health Authority, Energy and Natural Resources Authority, youth Authority and Justice Authority.)

With these bodies, the administration was able to control its areas, as the and Self- Defense Authority specialized primarily in military affairs related to People Protection Units YPG and women's Protection Units YPJ, but on July 21, 2014, the Defense Authority issued its first law under self-defense term, which states:

"Each family shall submit one of its members aged between 30-18 years in order to perform the self-defense duty lasts for six months."

Young people in the de facto Autonomous Administration regions didn’t make a response to that decision, as many of them have succeeded in avoiding performing compulsory military service in the ranks of the Syrian Regular Army since the Syrian conflict onset in 2011, because they live in the Kurdish areas, according to STJ reporter.

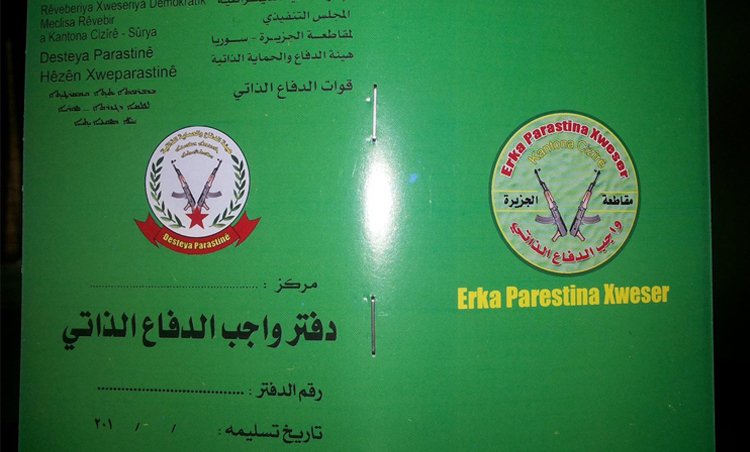

Image shows the book of self-defense duty in Autonomous Administration control areas.

Photo source: Activists from northern Syria.

Second: The Beginning of Compulsory Military Recruitment in Autonomous Administration Camps

On February 1, 2015, pro- Autonomous Administration Asayesh forces commenced an arresting campaign, on checkpoints within its de facto controlled areas, to forcibly recruit young people to the duty of self-defense, however, Hamid. X) confirmed, a young man from Qamishli city was pulled recruited despite being postponed, because he is a student, in this regard he spoke to STJ, saying:

"On November 1, 2015, I was on the way from Qamishli to al-Hasakeh to do exams, but at Al-Sabagh checkpoint, or known as the checkpoint at the entrance of al-Hasakah, I was stopped along with a number of young men, the elements asked for our identity cards, and to get out of the bus, then we were transferred to another bus and went to the Asayesh General Center in al Hasakeh, as they put us in a cell without any reason or justification, and after about (5) hours an element came and asked us to pledge to issue the self-defense duty books, and he told us that starting from today until a week, if we do not issue self-defense duty books, they will raid our homes and take us forcibly to the military service.

With that attitude, Autonomous Administration obliged many young people to issue books for self-defense duty. However, on January 16, 2016, Autonomous Administration prolong the period of the military service to nine months instead of six months, and in this regard Sahel Eyed -alias-(25), from Tell Brak located south of Qamishli, was forced to perform the duty of self-defense, although he is also considered "postponed" as he is student, he just says:

"On May 2, 2015, I was taken to compulsory service in Tell al Baydar military camp located northwest of al-Hasakeh; they kept telling us that our military service will be 9 months instead of 6 months pretexting that we have not been voluntarily entitled to military service."

Third: The Arrest of Scores of Youths in al-Hasakeh although they Excluded from Service

Parallel with the military operations launched by SDF to expel ISIS militants from Deir ez-Zur and Raqqa, Asayesh forces along with elements of the Military Police of the self-defense duty recruited dozens of youths to perform it, even if they are just 18 years old or below, or excluded from service for various reasons, according to STJ reporter, and in this regard Salman Kamal-alias-hails from al Hasakeh, said:

On July 15, 2017, I wanted to visit one of my relatives in Tal al-Hajar neighborhood located in al- Hasakeh, and when I arrived a military checkpoint, is known as industry roundabout/Dawar As-Sinaa checkpoint, its elements asked for my recruiting book, but unluckily it wasn’t with me, immediately I was put in a bus and taken to Autonomous Administration recruitment branch in Kalasa neighborhood, on the same day, I was taken to military service inside Camp of Ker Zero, located north east of al-Hasakeh, knowing I am a student at the Faculty of Economics. Next day my parents tried to review the recruiting branch to give them my recruiting book, and explain that I am postponed, as I am a student, but to no avail. "

In this context, Autonomous Administration issued a decision on December 28, 2017, to prolong the compulsory service months from nine months to a full year.

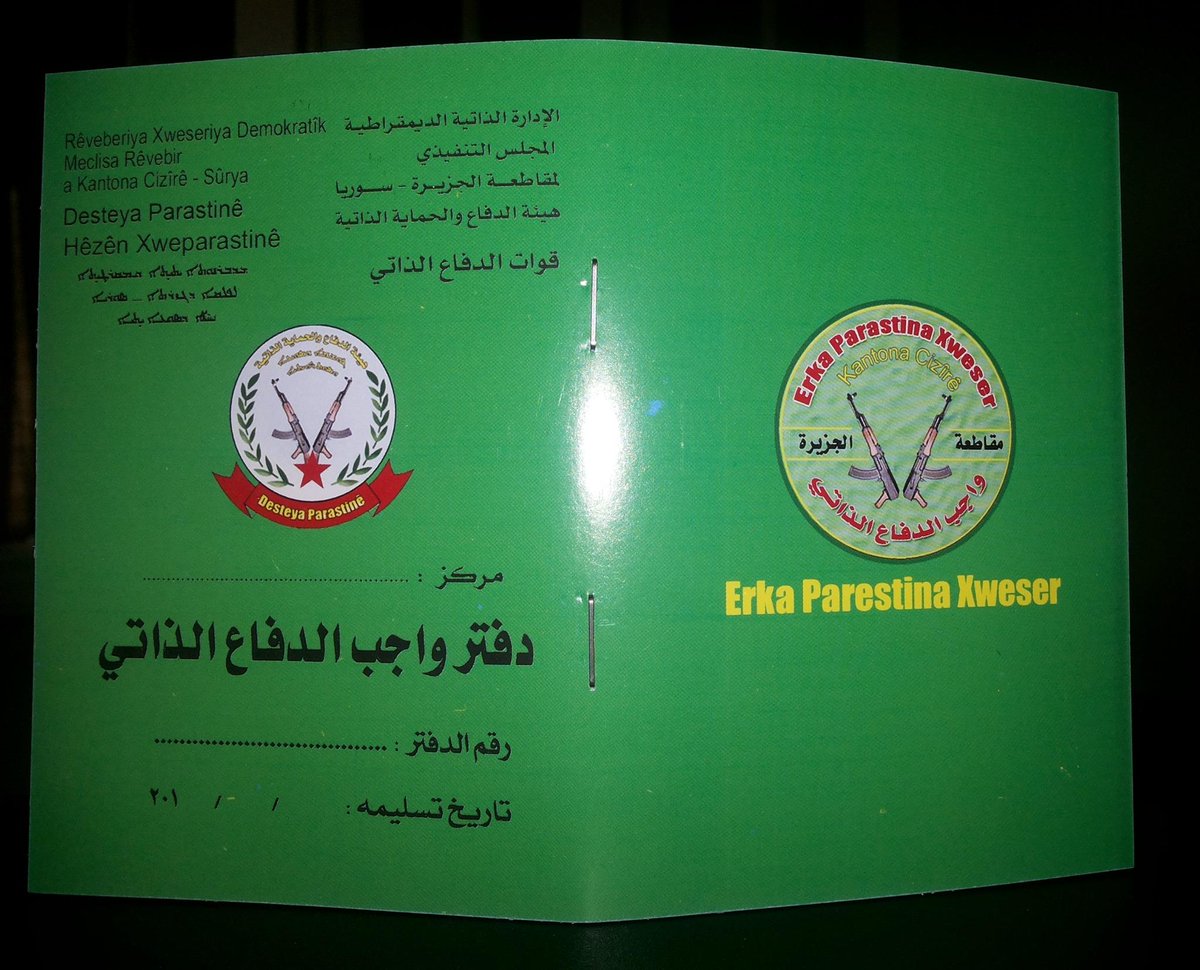

Image showing the decision of Autonomous Administration of the excluded cases from self-defense duty.

Photo credit: STJ

Abu Ahmed, a head of family and father of two young men, one of them was taken to perform the duty of self-defense in one of Autonomous Administration military camps located in the area of "Panorama" south of al- Hasakeh, on January 17, 2018, and in this regard he spoke to STJ saying

"Ahmed was a student at the Civil Engineering collage in Damascus, so he had a student postponement, but at the beginning of 2018, he was arrested by a military checkpoint elements in the centre of al-Hasakah, known as the" international checkpoint ", after one of the elements accused him of having a fake postponement, then he was initially taken to the recruitment branch in Qamishli, then directly to compulsory service, I tried to review the recruitment branch in Qamishli, and assured that my son was a "Master/AM" student, but they asked me to bring a certified health statement from his college, but when I contacted the college administration, they told me that there was a need for a legal agency and a security study to consider the study and postponement matters, but I have not been able to see my son Ahmed to sign the agency's legal paper so far. "

In another testimony, Salim Kh, father of 20-year-old young man who was forcibly recruited into the ranks of the self-Defense duty service on January 10, 2018. Although he is an employee in the Education field in al Hasakeh and he has a paper that allows him to postpone that duty, in this regard he spoke:

"On January 10, 2018, the Education Authority of Autonomous Administration asked my son and a number of teachers who teach with him at the Institute to attend an urgent meeting in Qamishli, on the way they were stopped by Autonomous Administration checkpoint elements, and then they were arrested and recruited, so I immediately reviewed the special recruitment branch in al Hasakeh, and in turn they told me that I should review the Education Authority in Qamishli, but they shocked me when they told me the postponing was no longer valid, even though it was not, and that my son is going to perform the self-defense duty like it or not. Therefore, I felt that meeting, where the teachers had been asked for, was only a ploy to set them up and take them forcibly for compulsory service.

Legal Framework:

On 21 July 2014, the Self-Administration authorities promulgated a law requesting each family to provide one of its members between the age of 18 and 30 for the performance of military service for a period of six-months. The time of service was subsequently extended to nine months and then to one year.

According to reports, individuals are often forcibly recruited after being stopped at military checkpoints. In addition, papers allowing the postponement of military service appear to be routinely ignored by the Self-Administration authorities.

This paper examines the international legal framework applicable to the forced recruitment of adults in the armed forces of a non-state actor.

The relevant bodies of law – Applicability

The two relevant bodies of law are International Human Rights Law (IHRL) and International Humanitarian Law (IHL).

As a general rule IHL applies only during armed conflict whereas IHRL applies both during armed conflicts and in times of peace. When applied in the context of an armed conflict, the rules of IHRL are partially modified to reflect the special circumstances existing during an armed conflict.[2]

Both IHRL and IHL are arguably relevant to the incidents in questions. It is now generally accepted that IHL applies not only in areas of active hostilities, but also to acts that occur elsewhere but are “closely related” to the hostilities.[3] The acts of forced recruitment arguably fall within the category of acts closely related to hostilities even if they occur in areas not directly affected by hostilities.

In a non-international armed conflict (NIAC) IHL applies both to states and to non-state organised armed groups. The Self-Administration is sufficiently organised for its armed forces to be bound by IHL.

The applicability of IHRL to non-state actors is currently debated by the doctrine. According to the traditional approach human rights obligations are binding only on states and do not bind other entities such as non-state actors. It is argued that the traditional approach has become progressively less persuasive and non-state actors such as the Self-Administration are equally bound by human rights obligations. A number of commentators support the notion that human rights obligations bind non-state actors especially when they exercise significant control over territory and population and have an identifiable political structure.[4] In addition, in the last two decades the UN Security Council adopted several resolutions calling on non-state actors to cease violations of human rights, therefore implying the applicability of human rights obligations on non-state actors.[5] Finally, the Self-Administration expressly and voluntarily confirmed its commitment to be bound by human rights obligations. In January 2014, the Self-Administration adopted the Charter of the Social Contract, the constitutional document for the territories under its control. Article 21 of the Charter states that “the Charter incorporates the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, as well as other internationally recognized human rights conventions.”[6]

The fact that non-state actors are bound by human rights obligations does not mean that they can be treated in the same manner as states. In most cases, non-state actors do not have the capacity to fully ensure the applicability of international human rights in the territory under their control and it would be inappropriate to expect so. With this in mind, the consensus between commentators is that the extent to which human rights obligations apply to non-state actors is context-dependent.[7] Non-state actors are bound to an increasing amount of human rights obligations depending on the extent to which they have displaced the state authority.[8] Non-state actors that have effectively displaced the state authority and which exercise exclusive control over a territory and a population, such as the Self-Administration, are therefore subject to significantly greater human rights obligations than a guerrilla group at the initial stages of insurgency.[9]

Forced recruitment under IHRL

Forced Labour

The first question raised by forced recruitment is whether the forced performance of military service constitutes forced labour under IHRL.

Article 8(3) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights prohibits to subject individuals to the performance of forced labour.[10] However, the Covenant specifies that “the term ‘forced or compulsory labour’ shall not include: […] (ii) [a]ny service of a military character […].”[11] Similarly, the International Labour Organisation’s Convention no 29 excludes the application of the forced labour provisions to military service.[12]

Recruitment by non-state actors

The main issue with the application of these rules to the Self-Administration is the determination of whether non-state actors can validly require military conscription. According to a more traditional approach, only States can legally require military conscription.[13] This approach appears to be based on the argument that only states can validly adopt laws.[14] If this approach were to be followed, the forced recruitment by the Self-Administration would arguably automatically constitute a breach of the human rights of those affected. During military service, the freedom of conscripts is inevitably restricted. In addition, the performance of military duties is mandatory. In normal circumstance, these restrictions/obligations do not constitute a violation of the human rights of the conscripts as international law allows states to require military conscription. If one followed the argument explained above, the same conclusion could not be reached in relation to military conscription required by a non-state actor. The limitations/obligations to which conscripts are subject would not be justified under international law and would constitute violations of the conscripts’ freedom of movement and of the prohibition of forced labour.[15]

In recent years a different approach has emerged concerning the ability of non-state actors to validly adopt legislation. In relation to the performance of judicial authority by non-state actors, some commentators now support the view that the rules adopted by such actors in that context may be considered to constitute “laws” for the purpose of international law.[16] If the same approach were to be applied in this context, the forced recruitment by the Self-Administration would not automatically constitute a violation of the conscripts’ human rights.

Requirements

Even if one accepted that non-state actors such as the Self-Administration have the ability to request military conscription, their ability to recruit is to be construed narrowly and must fulfil the following fundamental criteria.

– It must be prescribed by law;

– It must be executed in a lawful manner;

– It must be implemented in a way that is not arbitrary or discriminatory.[17]

In a case of forced recruitment undertaken in violation of these criteria, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights found the state responsible to have violated the individual’s rights to personal liberty, human dignity and freedom of movement.[18] The jurisprudence of the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights is obviously not binding on the Self-Administration and the findings of the Commission depended on the specific facts of the case. However, this case is indicative of the fact that instances of forced recruitment undertaken in an arbitrary or unlawful manner may amount to violations of a number of human rights including the right of freedom from arbitrary detention, the right of freedom of movement and the prohibition of inhuman and degrading treatment.

Forced recruitment as persecution under International Refugee Law

Under International Refugee Law (IRL) forced recruitment may, in some circumstances, constitute persecution and, if other requirements are satisfied, may entitle the individual subject to it to refugee status.[19]

Even though there is not a universally accepted definition of persecution, serious violations of human rights are generally considered to constitute persecution.[20] It follows that if an act is considered to constitute persecution under IRL, that act arguably represents a serious violation of human rights. In other words, instances of forced recruitment considered to constitute persecution under IRL arguably also constitute breaches of IHRL.

The UNHCR, the UN body competent for refugee related matters, appears to consider every instance of forced recruitment by a non-state actor as amounting to persecution.[21] This approach is once again based on the assumption that non-state actors cannot validly request and enforce military conscription as they cannot validly adopt legislation.

However, if one were to follow the more progressive approach according to which non-state actors can validly request military conscriptions, forced recruitment would amount to persecution only in the following scenarios:

– if the conditions of military service would in themselves amount to a serious breach of human rights;[22]

– if the armed group in which the person is forcibly recruited acts in violation of IHL or of IHRL and there is a reasonable likelihood that the person in question would be forced to commit such acts.[23]

If the performance of military service under the Self-Administration were to reflect the two scenarios described above, the act of forced recruitment could in itself constitute a violation of the Self-Administration’s obligations under IHRL.[24]

Conscientious objection

Another question to be considered is whether the Self-Administration recognises the right to conscientious objection. The right to conscientious objection implies the prohibition to force an individual to perform military service and to use lethal force if this ”may seriously conflict with the freedom of conscience and the right to manifest one’s religion or belief”.[25]

The right to conscientious objection to military service is not a right per se since international human rights instruments do not make direct reference to such a right. The right to conscientious objection is derived from an interpretation of the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion.[26]

Ne bis in idem

Finally, the international standards are clear that repeated punishment for continued refusal to perform military service is contrary to the ne bis in idem principle as established in article 14 of the ICCPR. The Human Rights Committee specifically addressed this situation in its general comment No. 32 (2007): “ Repeated punishment of conscientious objectors for not having obeyed a renewed order to serve in the military may amount to punishment for the same crime if such subsequent refusal is based on the same constant resolve grounded in reasons of conscience”[27]

Forced recruitment under IHL

The Third and the Fourth Geneva Conventions prohibit forced recruitment in relation to prisoners of war and in the context of occupation.[28] These rules are not applicable to the forced recruitments in the Kurdish controlled areas as the individuals affected are not prisoners of war nor is the area under occupation. More importantly, the rules in question apply only to international armed conflicts (IAC) and the Syrian conflict is currently considered to be – mainly – a non-international armed conflict (NIAC).

The 1907 Hague Regulations establish that “a belligerent may not compel nationals of the hostile party to take part in operations of war directed against their own country, even if they were in the belligerent’s armed forces before the war began”.[29] The rule now forms part of customary international humanitarian law[30] and is sufficiently wide in scope to be potentially relevant to the incidents in question. However, as a matter of principle the rule applies only to IACs.[31] One could attempt to extend the applicability of the rule to NIAC arguing that a party to the conflict may not compel someone that identifies with another party to the conflict to take part in operations against such party. However, such argument would not be particularly persuasive because in an IAC persons are linked to a specific party to the conflict by an objective criterion (nationality) and the same does would not apply to the scenario described.

It could also be argued that forced recruitment of civilians amounts to a breach of Common Article 3 to the Geneva Conventions. Common article 3 requires the parties to the conflict to treat humanely those who are not taking active part in hostilities.[32] The OHCHR addressed the question of forced recruitment by a non-state actor in its investigation on the violations committed by the Liberation Tigers for Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in the context of the conflict in Sri-Lanka. The LTTE had adopted a de facto one-person-per-family policy whereby each family within the area it controlled had to contribute one member and implemented this policy through acts of forced recruitment including abductions.[1] The OHCHR found the abductions by the LTTE leading to forced recruitment to be in breach of Common Article 3.[2]

Finally, the UN Guiding Principles of Internal Displacement address the question of discriminatory recruitment.[3] According to principle 13 (2): “Internally displaced persons shall be protected against discriminatory practices of recruitment into any armed forces or groups as a result of their displacement. In particular any cruel, inhuman or degrading practices that compel compliance or punish non-compliance with recruitment are prohibited in all circumstance.” The guiding principles are not binding, however they are an authoritative source regulating the treatment of internally displaced by all parties to the conflict. If forced recruitment targeted specifically internally displaced persons, it would constitute a breach of the principle in question. More generally, discriminatory recruitment would also amount to a violation of the obligation under Common Article 3 not to discriminate between those who are not taking part in hostilities.[4]

[1] On September 9, 2017 "Deir ez-Zur Military council" affiliated with the Syrian Democratic Forces/SDF launched the battle of "Island Storm", backed by international coalition forces in order to control the remaining southern countryside in Al Hasakeh which is under the control of the Islamic State/ISIS, in addition to eastern regions Euphrates, which administratively follows Deir ez-Zur.

[2] For more details on the applicability of IHRL during armed conflict and on the interaction between IHL and IHRL see: http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/HR_in_armed_conflict.pdf Section II, especially pp 46 to 68; https://casebook.icrc.org/glossary/human-rights-applicable-armed-conflicts; https://www.icrc.org/en/international-review/article/challenges-applying-human-rights-law-armed-conflict

[3] International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY) Tadic Appeal Decision para 69; ICTY Kuranac case, Judgement 12 June 2002, para 57. For additional information on the geographical scope of application of IHL see https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2785420&download=yes .

[4] See C. Tomuschat, A. Clapham, P. Alston, D. Murray. Murray lists the two following conditions: “the armed group must exist independently and