Executive Summary:

The 13th of November 2019 coincides with the 59th anniversary of the fire of the Shahrazad Cinema in Amuda City, al-Hasakah Province in northeast Syria, which the city bore witness to in 1960. The day commemorates a tragedy, that the collective Kurdish and Syrian popular memory recognizes as the Amuda Cinema Fire, during which over 200 elementary school students died, invited by the director of the Amuda District to attend one of the classic Egyptian movies at the cinema hall in solidarity with the back then-Algerian Revolution against the French Occupier (1954-1962), for the value of the tickets was to be sent to Algeria as a form of support to the revolution.

In 1960, the city of Amuda contained tow cinemas — the first known as the Fouad Cinema, and the second called Shahrazad. The Fouad Cinema was considered a summery hall while Shahrazad was designed for winter events, for it was built of clay and straw, in the fashion of the majority of the houses of this fertile agricultural area.

According to information obtained by Syrians for Truth and Justice/STJ, Khidir Izzo Makou, the owner of the cinema who is originally from Amuda City, designed the cinema as to have a folkloric decor, using gunny sacks[1] of different colored dyes. The hall was mostly built of wood, and the chairs were made of bamboo. The doors were also wooden with a padlock, which is locked only from the inside. In terms of accommodation, the cinema could host a maximum of 200 viewers only.

Invited by the director of the Amuda Distract, the principals of the area’s schools were informed of the necessity to back Algeria during the Algerian Revolution’s Support Week, which events included allocating one day to presenting movies to school students, on the condition that the income be donated to the revolution in Algeria, knowing that the price of the movie ticket was a quarter of a Syrian Pound back then. On this note, witnesses reported to STJ that buying the ticket was not compulsory, but those who did not pay for them were disdained.

The movie, screened back then, was called The Midnight Ghost[2], an Egyptian production that was not specifically meant for children, the people that STJ interviewed for the report said, pointing out that the film was old, repeatedly used and might have been obtained for free by the cinema managers. In their testimonies, all the survivors stressed that the fire started to spread from the film operation room, owing to the quality of the white and black films and the very basic means with which they were produced back then, making them flammable if played more than once. On that day, the mentioned movie was played for the third time in a row.

What made the matter worse was the massive number of children who came to attend the movie, for the hall was crammed with children beyond its accommodation capacity. While capable of hosting about 200 persons only, the number of children allowed in was way larger than that. The fire survivors added that back then Amuda had neither a fire station nor fire engines, for it was only a small town compared to the city it is today.

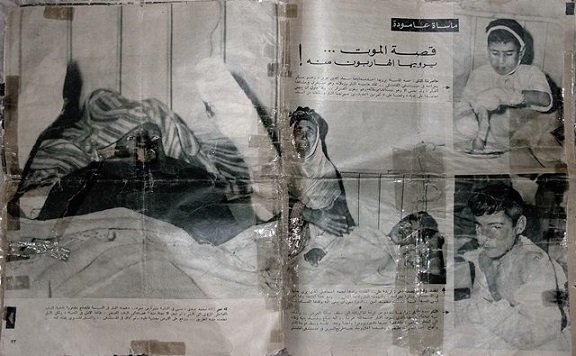

The majority of the children who burned to death were mostly students of al-Mutanabbi and al-Ghazali elementary schools, for the Egyptian newspaper of al-Mussawer/Photographer had documented the incident the next day and took a number of photos of the victims, the survivors, the injured, the tombs and the burned cinema. Back then, the newspaper reported the death of 193 children and the injury of 50 others.

Aziz Garis, one of Amuda City’s activists who documented aspects of the incident, informed STJ that they managed to record the death of 187 children, 21 of whom were buried in a mass grave in the Sharmoula Cemetery in Amuda. Other 3 children were buried in separate graves in the same cemetery, and 3 more were buried in cemeteries outside the city.

Of the dead victims, 3 belonged to the Syriac/Christian community in Jazzira; the rest, however, were all Syrian Kurds.

According to several sources, the government at the time, of the United Arab Republic, encompassing Syria and Egypt from 1958 to 1961, was negligent, for no serious investigation was made into the reasons for the incident or to find out the people responsible for the tragedy because the case was registered against unidentified persons, and the cinema’s location was turned into a public park after it was purchased by the municipality. The park, called al-Shuhada/Martyrs, is still open to the day with a memorial designed by Mohammad Jalal, an artist from Deir ez-Zor, shaped of children and a flag, symbolizing that of Algeria, as to indicate that the children died in support of the Algerian Revolution. In the following years, the successive Syrian governments prohibited the commemoration of the tragedy, and the reason is believed to be the prevention of any opportunity that would allow a space for addressing issues or voicing slogans irrelevant to the incident celebrated, especially since the majority of the area’s people are Kurds. Nonetheless, when the Syrian security services went absent from Amuda in 2012, and the Autonomous Administration was found in al-Hasakah Province in 2014, several of the city’s people resumed commemorating the incident in celebration of the memory of the people who died that day.

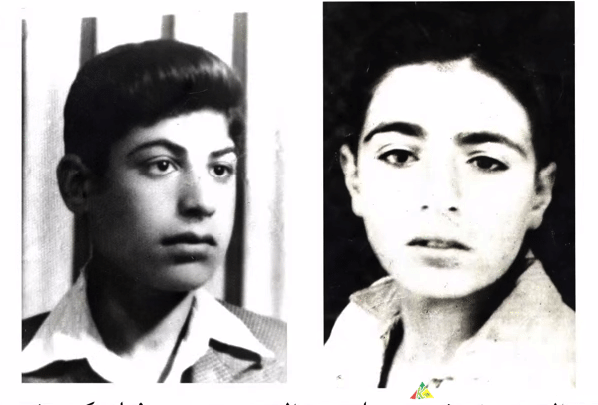

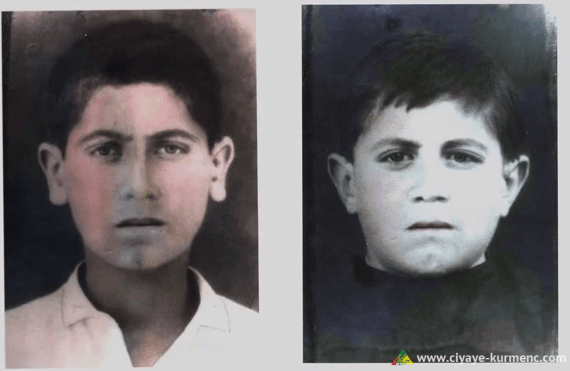

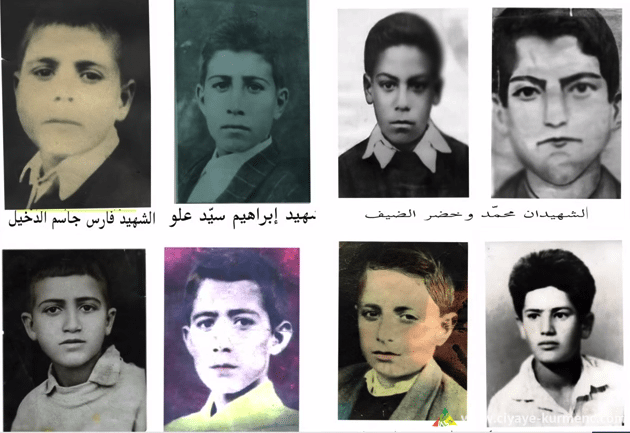

The photos 1, 2, 3 are of the children who died in the Amuda Cinema Fire in 1960. Photo credit: Local pages on social networking sites, covering happenings in Amuda City.

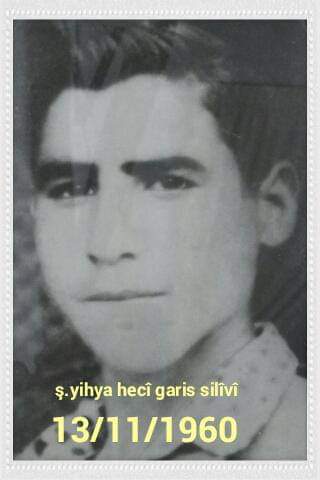

Photo no. (4)- The victim Yahiya Haj Garis Silivi, who back then was 19 years old. On the fire’s day, Yahiya went to bring his paternal cousin home. He burned to death as he tried to save the little boy. Reportedly, the Silivi family lost three members back then, who are Yahiya and Mahmoud Kilo Silivi and Abdulrahman Haj Hussain Silivi. Photo credit: The activist Aziz Garis.

Report Methodology:

The report is based on a total of (8) testimonies and interviews, conducted by STJ’s field researcher in person and online with eyewitnesses, survivors and locals in the period between early May and late November 2019, in addition to several other sources that document the incident.

It is important to mention that this STJ report is an attempt to complement the efforts made to document and to chronicle the incident of the Amuda Cinema Fire, including the book titled The Story of Amuda Movie Theater’s Fire by the author Mulla Ahmad Nami and another by author Qader Akkid, in addition to a third narrative by the lawyer Hassan Duraei, who published a two-volume book titled Amuda is Burning, among other authors.

1. How Did the Incident Start?

The incident started when hundreds of school students, the majority of whom were no more than 12 years old, were invited by the director of the Amuda District at the time to attend a movie at the Shahrazad Cinema. The invitation was an attempt to raise donations in support of the Algerian Revolution against the French Occupier, as reported by several survivors, who suffered and continue to suffer the agony of the tragedy, which took place 59 years ago.

Rasheed Fati, born in the city of Amuda in 1948, is one of the children who survived the fire. He goes back in time to the day of the incident, when he was yet 10 years old, recounting to STJ the following:

“They called the week Algeria’s Week, which meant that the cinema’s income was to be donated to Algeria. Back then, I was student at the al-Mutanabbi Elementary School. I still remember that on the incident’s day, they called the people to gather before the building of the municipality. Inviting them to donate for Algeria. The donation was not compulsory; it was actually semi-compulsory, for those who did not show up were expected to be disdained later on. The cinema, as I remember, was built of clay and mud, almost half a meter under the ground. The ceiling, however, was built of straw and timber. The doors were fit only for a barn. They screened the movie at 7:30 p.m. At the time, I was seated at the upper section. The movie stopped halfway through, and the screen went all white. I heard a sound and looked back; I saw the fire. The blaze was coming out of the movie operation room. We screamed and shouted: ‘Fire!’ We jumped off the upper section, which was about one and a half or two meters high. We jumped to the floor of the cinema hall.”

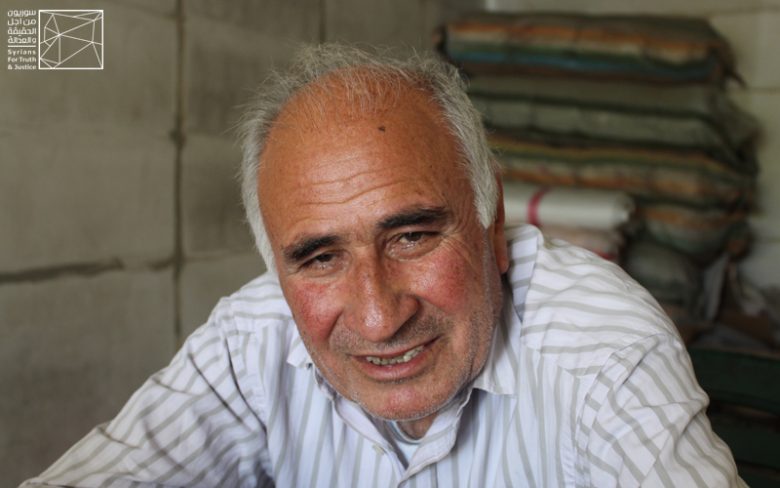

Photo no. (5) – The survivor Rasheed Fati. Photo credit: STJ.

Rasheed attempted to escape through the northern door of the cinema hall, but he failed, for the place was jammed. He then headed to the southern door, where children were crammed atop each other. He leaped over three children, during which he sustained second-degree burns in his leg. He continued his account, adding:

“We were outside and could finally breathe. The fire was still raging. I looked back; it was exactly like hell and fire was coming out of the windows. Back then, they crammed about 400 children into the hall, which could accommodate 200 to 300 persons only. They were all children. Back then, we heard that the operation room at the cinema hall contained about 300 kilograms of film strips, which all caught fire.”

Ibrahim Shaikho, born in the city of Amuda in 1948, is also one of the children who survived the incident, one who is yet haunted by the burns he sustained back then. Ibrahim told STJ the following:

“I was a fourth-grader back then. They distributed to us the tickets to a movie at the Shahrazad Cinema, which at the time were priced at a quarter Syrian Pound. All that I remember is that I sought the hall and before the movie ended, fire was feeding on the place. The source was the film operation room. All the attendees were children; some of whom had even throw themselves from above. I hurried to a small shop inside the cinema. I entered it with other 20 children. We stayed there until fire reached the screen and spread throughout the hall, to the moment when the ceiling collapsed.”

Ibrahim was saved after he sustained severe burns in his arms and legs while a number of his mates suffocated. He was rushed to the al-Qamishli National Hospital, where he spent about a month, pained by his burns.

Photo no. (6)- The survivor Ibrahim Shaikho. Photo credit: STJ.

2. The Incident is Effected by Negligence:

According to the many accounts provided to STJ, on the incident’s day, hundreds of children flocked into the hall, filling its space beyond capacity. The fire started to spread from the film operation room, extending to the full range of the hall, built of wood mainly. Most of the witnesses attributed the fire to negligence, especially the overuse of the film, made of flammable materials.

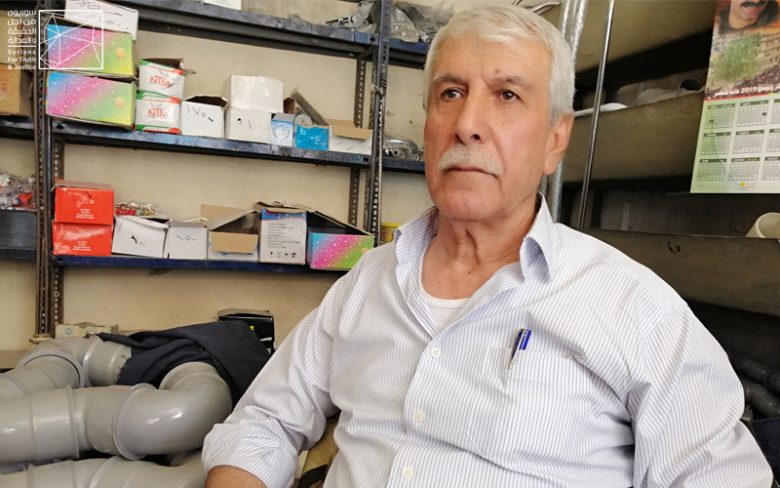

Ibrahim Issa, born in the city of Amuda in 1937, is one of the staffers who sued to work in Shahrazad Cinema in 1960, the year which marked the incident. He narrated the following to STJ:

“The movie, screened on the cinema’s fire day, was an Egyptian classic, called The Midnight Ghost. Playing the movie was banned at the time, for it was a scary movie and full of horror scenes, totally unfit for children. The movie’s film strip resembled those used for the old cameras, which substance would caught fire once exposed to heat. The film strip was made in Egypt. The first time the movie was screened, the ticket was priced at a quarter of a Syrian Pound. The first time was dedicate to little girl students. The second time, however, the audience was all boy students. The same movie was shown on the two times. The film was expired and its gears broken. The device that contained the film was box-shaped, in the rear part of it there were a mirror and two connected pieces of coal. The latter would provide the mirror with light, which in turn directs it to the lens. Next, the lens would provide the screen with light. The temperature of the two coal pieces was really high; it could burn the hand. The film was thus on fire and got torn out on the second time.”

Photo no. (7) – The survivor Ibrahim Issa. Photo credit: STJ.

Issa continued to say that the fire raged in the cinema hall, which was made of wood and log, reaching the ceiling at a certain point. He added:

“Ten minutes before the fire, I went up, for it was a hot unbearable weather. In the hall, I saw a woman that came to the movies for the first time, carrying a child on her shoulder, with another beside her. A friend came to the cinema and asked me to come out for a chat. We were about 50-100 meters away from the cinema. And then, we noticed that the power was out, and the people were running opposite to our direction. It was between sunset and evening [when this happened]. Someone told me why would not you look behind and see the fire coming out of the cinema’s window? We head back to the cinema. The people congregated there and pour water on the windows but to no avail. There were two doors to the cinema, one leading to the northern street, and another to leading to the south. The cinema was like a basement; it was on fire, and the children escaped, they were all between 10 and 12 years old. When they attempted escape and sought the stairs, the tragedy took place, for the door was old and made out of worn-out wood; it was locked from the inside. The children shoved against each other and totally blocked the door. The people tried to open the door from the outside, but it was all to no use.”

Issa added that about six children managed to flee through the southern door of the cinema hall, which overlooked a water well. Three of the children fell down the dry hole. He recalled what happened then, saying:

“There was a small shop inside the cinema hall, where snack were sold. Inside it, 13 children were stuck, so the people gathered and tried to rip the door open but failed to do it. As a result, all the children burned to death. I remember that one of the people, called Mohammad Saed Agha, tried to save the children, for his son was inside the cinema hall[3]. He managed to save six of them from the fire. It was the moment when the Police came and told us: ‘The situation is dangerous to all of you, for the walls will collapse, and no one is left any hope to save his children because the fire was coming out of the door.’ Mohammad Saed Agha wanted to go inside again, but the policeman prevented him. The former insisted and charged inside to never come back again. The ceiling crumbled. The tragedy was beyond description, for about 200 children burned to death, and another 50 were injured. I also recall that they placed the bodies of each 5-6 children in the same grave because they were not capable of recognizing the names due to the severe burns.”

Issa concluded his account saying that, after the incident, a relief organization visited the affected families and offered them blankets and money. Each of the families that lost a child was given 3000 Syrian Pounds[4]. In addition to this, the Syrian Government bought the land—where the burnt cinema was built— from its owner and turned it into a public park that today is known as the al-Shuhada/Martyrs Park.

Sideek Aousi Shaikhmous, born in the city of Amuda in 1932, is one of the people who helped in building the Shahrazad/Amuda Cinema when it was first founded and another witness to the incident. He told STJ the following:

“I worked as a carpenter and helped in building this cinema. We have constructed it of clay and supplemented the ceiling with plate-iron girders, atop of which we added timber, straw and then dust. The cinema had two doors, one to the south and another to the north. Both doors were made of wood. I wanted to build large doors that can be opened from the outside, so that the attendees would be capable of escaping if anything happens. However, the owner of the cinema, Khidir Makou, refused that, saying: ‘we will design the doors with a lock on the inside.’ We also built stairs, where the viewers could sit, consisting of stepped benches, which we created out of wood and timber. Even the floor was made of wood.”

Commenting on the incident, Sideek added:

“When the cinema went ablaze, I was at home. I do remember that we heard screams and wailing. We inquired into the matter? They said that the cinema has burned down, and inside it were many children. We ran there, and the police was dispersing the people, so they would not approach the fire. I went there to help them. The door was locked, and a person, by the name Mohammad Saed Agha, tried to open it and failed. The latter jumped over the fence and entered the cinema through its southern door. He succeeded in saving the life of several children. When the hall’s ceiling collapsed, we broke the door open. The children were crammed atop each other. They had all sustained burns. When we opened the door, their bodies were scattered everywhere we stepped. I was there at that moment, I carried a child; a second person carried another child to take them to the dispensary. The children battled against death. We went through a lot just to rush the children to the dispensary, for there were many dead children, who were being taken to the mosque.”

Photo no. (8) – The witness Sideek Aousi Shaikhmous. Photo credit: STJ.

Sideek pointed out that several policemen have taken their children out of the cinema before the fire broke out, adding that most of the families in Amuda city had lost a child or two in the incident. His family, for its part, lost his paternal cousin who died in the fire, in addition to two children who got wounded that day.

3. The Incurable Wound:

The Shahrazad/Amuda Cinema Fire caused the death of over 200 children and the injury of dozens, according to the testimonies offered by survivors to STJ, who still remember the incident as if it took place only yesterday, for they are yet coerced into dealing with its physical and psychological repercussions to the day.

Husam al-Din Shaikhi, born in Amuda City in 1944, was one of the children who sustained burns during the fire that broke out in the Shahrazad/Amuda Cinema in 1960. He gave STJ an account of the incident, saying:

“I was a sixth-grader, a student of 12 or 13 years old, when the cinema went ablaze. I remember that we were poor, rather, penniless. I died to get that quarter of a Syrian Pound. I bought the ticket to the Egyptian movie that was being screened at the time. My turn was at six p.m. I went there ten minutes earlier and jumped over the fence and the wires. The doors were all open, and the place was extremely overcrowded. I remember that the seats were made out of wood and bamboo. Only a few minutes passed, when the people started to scream: ‘Fire!’ The flames were embracing each other. The screaming went higher, and we started pushing against each other. The door was about 10 meters away from me; I leaped over the children. The cinema’s guard caught me, and I went out through the northern door.”

Photo no. (9) – The survivor Husam al-Din Shaikhi. Photo credit: STJ.

Shaikhi added that the majority of the people who burned to death were children, for he still remembers how the children were in a hurry to exit through the hall’s northern and southern doors, saying that if the doors were well-made, everyone would have managed to flee and survive. He continued to say:

“I recall that one of the children returned to get back his shoes, but he burned to death. The shoes were new and the people impoverished. All that I can remember is that the bodies turned to ashes, and that my right eye was injured due to the high temperature. I still have a vision impairment to date. The film they used was affected by heat and was on fire. After the incident, all the cinemas in the Jazira region were censored, and the films were provided with a tag, on which the film’s production date, address and story were written. However, before the fire, the [cinema owners] used to randomly buy the films from the al-QAmishli’s market. If it was a thrilling one, they would go for it. The owners of the Fouad and Shahrazad cinemas had brought the film from the first hall to the second, saying that the income would be sent to Algeria, doing no promotion for the film. Even the school teachers did not inquire into the movie’s story, and I do believe that the cinema’s owners did not actually purchase the film but managed to get it for free.”

Mohammad Ameen Abdulsalam, born in the village of Qahfakah, rural Amuda, in 1948, is another witness to the incident. Back then, he was a sixth-grader. He narrated the following to STJ:

“My maternal cousin bought the tickets, but his mother prevented him from attending the movie, so I went there instead of him. I remember putting on new clothes for the cinema. To tell the truth, the cinema, back then, was fit to be a barn. The floor was made of dust, and it was very deep under the ground. The hall’s chairs were made out of clay. The place was extremely crowded. I remember that someone screamed: ‘Fire!’ And each of the children attempted to save himself. The door, nonetheless, got locked on the inside, due to crowdedness and elbowing. I withdraw from the crowed and entered a small shop in the hall. Others started coming in. The fire was too fast to expand. Some children were crying; some were burnet, one of them was still alive, called Ahmad al-Qaderi. Another child, by the name Ibrahim Hammi, burned to death next to the door.”

When the cinema’s ceiling collapsed, the children tried to find a way out. While fleeing, Abdulsalam sustained severe burns in his leg and arm. Affected by the injury, he passed out and was rushed to the dispensary. The next day, he was transferred to the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou were he was to receive treatment.

Photo no. (10) – The survivor Mohammad Ameen Abdulsalm. Photo credit: STJ.

Majoul Hasan Kon Rush, born in the city of Amuda in 1949, is one of the children who survived the fire. He told STJ that, on the day of the incident, he accompanied his paternal cousin, neighbor, and the son of the Police Department’s Director to the Shahrazad Cinema. He said:

“Back then, I was a fourth-grader. When we went into the cinema, I sat next to the door, along with my neighbor. My cousin and the son of the Police Department’s Director, nonetheless, settled in the upper part, which was mostly made of wood and timber. The film was on fire shortly after it started. I looked behind and saw the fire raging in the film operation room. In the beginning, I did not care. But, five minutes later, the fire spread from the operation room to the hall. The children threw themselves from above. It was then when I knew that the situation was not that simple. We immediately went on the street. Ten minutes into the fire, the scene became eerie. The door I left through was locked by the children crammed behind it. The second door, the one that led to the street, was also shut for the same reason. The cinema’s windows were about four meters high. The children climbed over each other, becoming as high as the windows. I escaped home and told my mother that the cinema had burned down.”

Photo no. (11) – The survivor Majoul Hasan Kon Rush. Photo credit: STJ.

The photo is taken from Amuda’s local pages on social networking sites, showing several survivors, including a child embraced by his mother. She is called Farida and is the mother of the famous Kurdish writer Delawar Zanki.

[1] Bags designated for filling wheat during the harvest season.

[2] Other sources mentioned that the screened movie was called A Midnight Crime, but the more accurate narrative is the one calling the movie The Midnight Ghost, since the film was produced in 1947.

[3] One of the sources told STJ that Mohammad Saed Agha’s son was among the batch that attended the second round of the movie, not the third which witnessed the fire. The people informed Mohammad that his son Fahed was not in the cinema during the fire and that he was at home, to which he answered, saying: “The children of Amuda are all Fahed!”

[4] Several of the families refused to accept the compensation.