This publication was funded by the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of (Ceasefire centre for civilian rights/STJ) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.

1. Introduction

1.1. Context of the Declaration

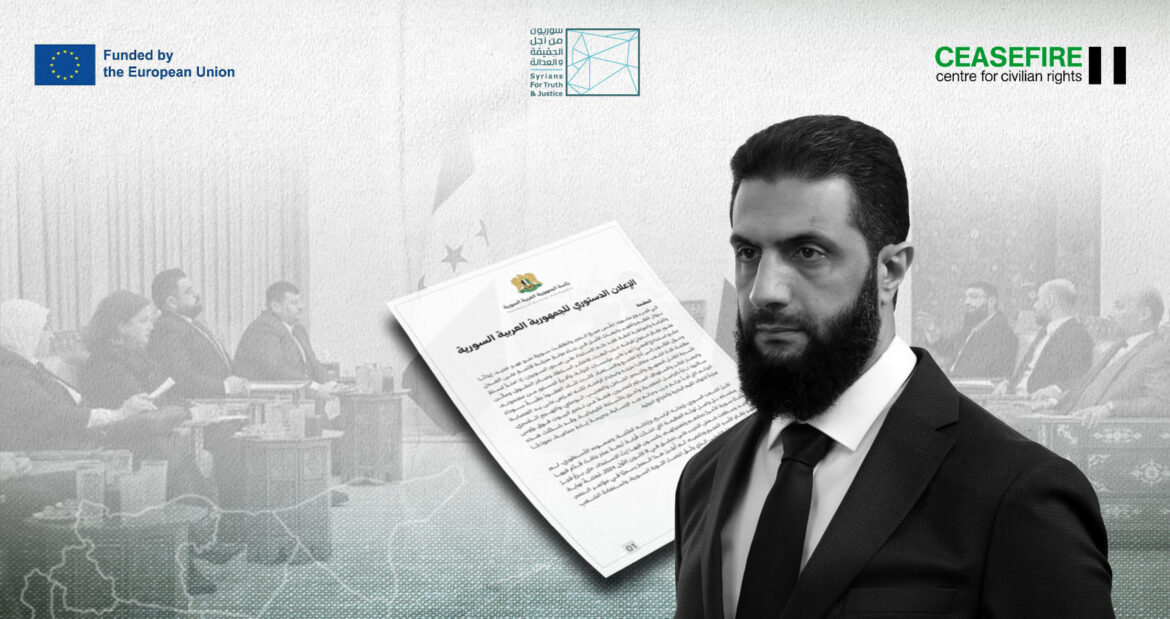

After the suspension of the 2012 Constitution, and pursuant to the statement issued by the so-called “Victory Conference” on 29 January 2025, the Syrian Transitional Administration announced on 2 March the formation of a committee composed of seven legal experts tasked with drafting a constitutional declaration for the upcoming transitional phase.

In addition to the “Victory Conference” statement, the formation of the drafting committee was also based on the outcomes of the “National Dialogue Conference” held in February 2025, which called for preparing a constitutional declaration to pave the way for a transitional period grounded in the rule of law, justice, and citizenship. According to its preamble, the declaration also drew upon the Independence Constitution of 1950.

Despite relying on references that were intended to grant it historical or consensual legitimacy, Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) believes that the declaration raises critical concerns regarding its legitimacy, its content, and its actual capacity to meet the aspirations of Syrians after more than a decade of uprising and suffering. The declaration is neither presented as a temporary, time-bound transitional document nor as a permanent constitution derived from the free will of the people. Instead, it takes on a hybrid form —exceeding the framework of a temporary arrangement without rising to the level of a complete constitutional text— a form that may reflect superficial flexibility but opens the door to profound legal and political challenges.

The declaration, consisting of 53 articles, sets out the foundations for a detailed system of governance that could persist for years, without being the product of a genuine and inclusive national debate or the result of a transparent participatory process. Rather than paving the way for a genuine democratic transition, there is a fear that it could be used as a tool to reproduce centralized authoritarian rule and entrench exclusionary practices under a new legal guise, thereby undermining the pluralistic constitutional foundation that should accompany the country’s moment of political transformation.

The committee submitted the draft transitional constitutional declaration to Transitional President Ahmad al-Shar’a, who signed it on 13 March 2025, establishing it as the constitutional reference for the transitional period, which the declaration set at five years.

1.2. The Syrian National Dialogue Conference

The Syrian National Dialogue Conference was held in Damascus on 24–25 February 2025 with the aim of launching a consultative process to pave the way for drafting a constitutional declaration and outlining the features of the coming phase. In preparation for the conference, a preparatory committee consisting of seven members hosted discussion sessions across various governorates and consulted with approximately 4,000 people to collect views that could help shape a vision for the constitutional declaration, a new economic framework, and an institutional reform plan.

Despite the symbolic and political significance carried by holding the conference, it sparked a wide wave of criticism from the moment it was announced, targeting both its form and its content. The preparations for it were seen as hasty and brief, with the announcement made only two days prior to its convening, which many invitees considered an indication of a lack of seriousness and sufficient preparedness to address such an important national milestone. This led some political and academic figures to decline the invitation.

Serious questions were also raised regarding the representation of political and ethnic components, as the Kurdish National Council pointed to the exclusion of influential forces from the invitation list and considered that participation was conducted in a selective manner that did not reflect the principles of national partnership. Moreover, the conference lacked clear mechanisms for implementing its outcomes or ensuring follow-up on its recommendations, raising doubts about its effectiveness and its ultimate results.

As for its final statement, despite affirming concepts such as “the unity of Syria” and “its sovereignty,” it was issued in a general form, stripped of any concrete commitments, particularly in light of the absence of a timeline or a detailed vision for the transitional process. Accordingly, the conference appeared closer to a message directed at the international community than to a genuine national dialogue platform that expressed a unifying national political will.

1.3. The Committee for Drafting the Constitutional Declaration

The announcement of the formation of the committee tasked with drafting the constitutional declaration on 2 March 2025 raised numerous questions regarding the transparency and seriousness of the process. Although the committee had not officially announced the commencement of its meetings, content from the draft began to leak to the media within hours of the presidential decree. Non-Syrian media outlets, including Al Jazeera and Al Modon, published excerpts from the declaration’s provisions and later a near-complete draft consisting of 43 articles, even before it was known whether the committee had actually held its first meeting.

This suspicious timing reinforced the perception that the draft—or the majority of its content—had been prepared in advance, and that the committee was formed later merely to give a formal legal veneer to a prearranged decision. The absence of any official clarification from the relevant authorities raised legitimate questions about the transparency of the drafting process, the respect for the principle of participation, and whether there would be opportunities for the public to engage with and examine the mechanisms for building the constitutional framework for the transitional phase.

As for the committee’s composition, it consisted of seven legal experts, including two women. Despite the academic backgrounds of the members, their areas of expertise were limited exclusively to the legal field, with no representation of experience in politics, economics, or the social sciences, which raises concerns in a transitional context that requires multidimensional approaches.

It is also notable that most committee members shared similar intellectual orientations, reflecting a bias in its formation and excluding a broad spectrum of national competencies that had emerged during the Syrian uprising, especially those involved in political and constitutional debates over the past years. Rather than serving as a mirror of the intellectual and political diversity within Syrian society, the committee remained confined to a narrow technical-legal framework, thereby weakening its representational legitimacy and its capacity to produce a constitutional text that reflects the pluralistic character of the upcoming stage.

Furthermore, the committee lacked genuine representation of ethnic and religious components and did not sufficiently consider gender balance — with only two women among its seven members — nor did it reflect diversity of identities and orientations. This entrenches the committee’s limited inclusiveness and representativeness, undermining its prospects for building a broad-based social contract through its work.

1.4. Methodology and Core Themes of this Paper

This paper is based on a critical analysis of the Syrian Transitional Constitutional Declaration issued in March 2025, through a comparative legal and political reading that takes into account the current transitional context in Syria, and draws upon international constitutional standards as well as Syria’s legal obligations under treaties it has ratified.

The paper does not approach the declaration merely as a procedural transitional document, but rather treats it as a foundational and pivotal text that is supposed to lay down the contours of the upcoming political system and define the nature of the relationship between the state and society. Within this framework, the paper examines the declaration through three core themes that constitute fundamental pillars of any democratic transformation process:

- The principle of separation of powers and the powers of the Transitional President of the Republic

- The extent to which transitional justice is incorporated as a comprehensive and fair mechanism

- The inclusivity of the declaration in reflecting the various components and diverse identities of Syrian society

These themes are supplemented by a comparative analysis linking the 2025 constitutional declaration with Syria’s previous constitutions of 1950, 1973, and 2012, in order to measure the degree of progress or regression in the core constitutional principles addressed in the paper.

The paper does not claim to cover every aspect of the text but rather focuses on those elements that affect the deep political and constitutional structure and directly influence the legitimacy of the transitional phase and the pathways for building a new social contract.[1]

2. First Theme: The Powers of the Transitional President of the Republic and the Issue of Separation of Powers

The principle of separation of powers is one of the fundamental pillars of any democratic system that respects the rule of law. It is an essential safeguard to prevent the concentration of power in the hands of a single person or entity and to ensure that each branch is accountable to the others. The transitional constitutional declaration, in its Article 2, states: “The state shall establish a political system based on the principle of separation of powers.” However, it contradicts this principle in its other articles by enshrining an almost absolute presidential dominance.

2.1. Concentration of Powers in the Hands of the President and the Absence of Institutional Balance

According to the constitutional declaration, the transitional president holds near-absolute executive and legislative powers, including the issuance of decrees, and laws approved by the People’s Assembly / Article 39, appointment of the government, declaration of a state of emergency, appointment and dismissal of senior officials, and ratification of treaties. The declaration deprives the People’s Assembly of the power to impeach the president, to vote on granting or withdrawing confidence from ministers, or to exercise effective oversight over the executive branch.

2.1.1. Appointment of Members of the People’s Assembly:

Article 24 grants the Transitional President of the Republic the authority to form a higher committee that selects the members of the People’s Assembly and supervises the election of two-thirds of them through subsidiary bodies. As for the remaining one-third, the president appoints them directly.[2] This arrangement subjects the legislative authority to presidential dominance, by combining the power to oversee the electoral process with the authority to appoint members of it, which contradicts the principle of separation of powers, undermines the institutional independence of the Assembly, and strips the elections of their representative substance.

2.1.2. Enshrining Noble Values and Virtuous Morals

Article 33 also adds a dangerously ideological dimension by granting the Transitional President the authority to “promote noble values and virtuous morals,” a vague phrase often used to justify restrictions in the name of ethics or religion. This phrase represents one of the most dangerous ideological formulations in the declaration, as its conceptual ambiguity allows it to be used as a restrictive tool to justify repressive policies. Moreover, it contravenes the principle of legal certainty, which requires clarity of rules and provisions, and threatens intellectual and political pluralism in the name of “values.”

2.1.3. Signing International Treaties

Article 37 further provides that the Transitional President of the Republic shall have the “final signature” on treaties concluded with states and international organizations. However, conferring a “final” nature on the president’s signature creates ambiguity regarding the sequence of procedures for ratifying international treaties, such that the People’s Assembly’s ratification under Article 30 of the declaration[3] has no legally binding effect if it is not coupled with the approval of the Transitional President. If the latter refuses to sign, the treaty’s entry into force is blocked, and the People’s Assembly has no constitutional means to complete or override the process.

2.1.4. Declaration of War, General Mobilization, and the State of Emergency:

Article 41[4] grants the Transitional President of the Republic extensive powers to declare war and general mobilization, as well as to declare a state of emergency, based on the approval of the National Security Council, without requiring the approval of the People’s Assembly (bearing in mind that the composition of this Assembly suffers from structural imbalances and weak independence, as noted above).

It should be noted that the National Security Council was established by a decree issued by the Transitional Syrian President Ahmad al-Shar’a on 12 March 2025, just one day before the issuance of the Constitutional Declaration. The Council consists of seven members, chaired by the Interim President, and includes the Ministers of Foreign Affairs, Defense, and Interior, the Director of General Intelligence, along with three members appointed by the president: two advisors and a specialized technical expert.

While Article 41 requires consultation with the head of the People’s Assembly and the President of the Constitutional Court (who is appointed by the President of the Republic) in the event of a state of emergency, the decision essentially remains in the hands of the Transitional President of the Republic. The approval of the People’s Assembly is required only to extend the state of emergency after its initial three-month period expires. These powers raise questions about the balance of powers, particularly since the adopted formulas do not impose genuine parliamentary oversight before taking critical decisions, such as entering into war or restricting rights and freedoms.

2.1.5. Amendment of the Constitutional Declaration

Article 50 of the Constitutional Declaration provides for the possibility of amending it “with the approval of two-thirds of the People’s Assembly upon the proposal of the President of the Republic.” This formulation raises concerns in a transitional context that is supposed to be based on participation and mutual oversight. Restricting the right to propose amendments solely to the interim President entrenches executive dominance and excludes other authorities and political and societal actors from contributing to the revision of the constitutional framework governing the transitional period. Moreover, requiring the approval of two-thirds of the People’s Assembly does not constitute an adequate safeguard, given the lack of guarantees for its genuine representation of political and social pluralism. This arrangement lacks the principle of separation of powers and weakens oversight over the executive branch, potentially opening the door to substantial amendments being carried out unilaterally or without genuine national consensus.

2.2. Subordination of the Judiciary and the Weakening of its Independence

With regard to the judiciary, the Supreme Constitutional Court — the body theoretically responsible for overseeing the constitutionality of laws — is appointed exclusively by the President (Article 47), effectively making it an executive tool under a judicial guise. This problem is compounded by the continued application of the Judicial Authority Law of 1961, which keeps the judiciary administratively and financially subordinate to the executive branch, in violation of judicial independence. Under this framework, the President of the Republic chairs the Supreme Judicial Council and is represented by the Minister of Justice (Article 65), who in turn presides over half of the Council’s members subordinate to him; the Deputy Minister of Justice is an employee of the Ministry of Justice, and the Head of the Judicial Inspection Department is also an employee reporting to the Minister of Justice. Moreover, the Minister of Justice heads the Public Prosecution, which means he supervises the Prosecutor General, further reinforcing his dominance over members of the judiciary, stripping the judiciary of its independence, and depriving judges of their immunity.[5]

This presidential model has been widely criticized by Syrian and international organizations, including a report by Human Rights Watch, which considered that the declaration limits the judiciary’s ability to hold the president accountable because of “the authority to appoint all seven members of the Higher Constitutional Court without parliamentary or other oversight. Without mechanisms to guarantee judicial independence or the creation of an independent body to oversee judicial appointments, promotions, discipline, and removals, the judiciary”.

To Read or Download the Full Paper in PDF Format, Please Click here.

[1] Syrians for Truth and Justice has prepared a legal paper on the key constitutional principles that the Syrian constitution should include, so that the constitutional process serves as a transformative tool for positive change. Syrians for Truth and Justice. “Syria’s New Constitution: Ten Constitutional Principles for a Just and Inclusive Democratic State” 31 January 2025.

[2] On 13 June 2025, the Transitional President of the Republic issued Presidential Decree No. 66 of 2025, establishing a committee called the “Higher Committee for People’s Assembly Elections.” The decree tasked the Higher Committee with overseeing the formation of subsidiary electoral bodies, which would in turn elect two-thirds of the members of the People’s Assembly. https://www.sana.sy/?p=2231640

[3] Article 30 of the Constitutional Declaration states the following: “The People’s Assembly shall undertake the following tasks… (c) the ratification of international treaties.”

[4] Article 41 of the Constitutional Declaration provides as follows: (1) The President of the Republic shall declare general mobilization and war after the approval of the National Security Council.(2) If a serious and imminent threat arises that endangers national unity or the safety and independence of the homeland, or hinders state institutions from carrying out their constitutional functions, the President of the Republic may declare a partial or total state of emergency for a maximum period of three months, in a statement to the people, after obtaining the approval of the National Security Council and consulting with the Head of the People’s Assembly and the President of the Constitutional Court. It may be extended once more only with the approval of the People’s Assembly.

[5] For more details, see: Syrians for Truth and Justice. Syria: The Interference of the Executive Branch in the Judiciary and its Impact on Safeguarding Democracy. 22 February 2025