It has been four years since Operation Peace Spring launched by Türkiye and allied Syrian opposition armed group against Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî, north-eastern Syria. The Operation, which was started on 9 October 2019, resulted in Türkiye’s full control over the two cities and parts of their surroundings, reaching the M4 highway, which lies 30 to 35 km deep in Syrian territory. The Operation was suspended under two separate agreements Türkiye signed with the United States (U.S.) and Russia on 17 and 22 the same month.

Operation Peace Spring reshaped the map of control in favor of Türkiye at the expense of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and the Global Coalition to Defeat Daesh/IS and led to a demographic change and displacement of the original population. This had numerous persistent impacts on civilians and ruined the area’s unique diversity, which fused different religions and nations including, Syriac, Assyrian, Armenian, Chechen, Arab, Kurdish, Turkmen, and Mardali.

Chechen civil activist, Rayan Akhteh, said in this regard:

“Anyone who knows the social and cultural composition of the city of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê is fully aware of the obliteration of its identity which was full and rich of the spirit of brotherhood, peaceful coexistence, and solidarity. This identity is not the result of chance but of a heritage passed from generation to generation, over time, despite all the dramatic changes our country went through. Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê opened its door to displaced families fleeing hostilities from different Syrian provinces and was exemplary in hospitality.”

The writer and researcher, Shoresh Darwish, believes that Operation Peace Spring originally targeted the Kurdish social structure explaining:

“Before the Operation, we heard the speech of Türkiye’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in which he indicated that the nature of the area, referring to Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê, does not fit the Kurds’ lifestyle. Moscow and Washington were at the time colluded with Erdoğan approach to the area. We are facing a policy of resettlement and an occupation based on uprooting the indigenous population and replacing them with others.”

Operation Peace Spring resulted in the forced displacement of hundreds of thousands of original people. A large number of those displaced stayed in makeshift camps set later by the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) including, Serê Kaniyê/al-Talae’, Tel al-Samen, Washo Kani/al-Twaina, and Newroz Camps, while others were distributed in north-eastern Syria, mainly in al-Hasakah, Raqqa, and Qamishli or immigrated to Iraqi’ Kurdistan or European countries.

Four years have passed since Türkiye’s occupation of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê, yet %85 of its population is still forcibly displaced. The area lost its diversity; its Kurds who were 75,000 people before the Turkish invasion are now no more than 45 people, and the number of the last Armenians, Syriacs, and Yazidis is less than 10 while most of its Arabs, Chechens, and Circassians were displaced. Meanwhile, Türkiye settled 2,800 families displaced from different Syrian parts as well as the refugees it deported, including Iraqi families of Daesh/IS fighters, in the original people’s homes.[1]

Journalist Shira Ousi who hails from Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê recounted on the exhausting displacement journey:

“The displacement process of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê population was painful. Children, the disabled, and the elderly shared this experience alike. Many families dispersed and others lost their children or could not feed them. We saw children without milk and helpless mothers crying blood on their starving children. We were heading into the unknown.”

One major consequence of the Operation is Turkification, which is clearly visible in the Syrian areas occupied by Türkiye. A few days following the cease of Operation Peace Spring, the Turkish forces and allied Syrian armed factions raised the Turkish flag over the cities of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî. This was followed by; the entry of Turkish relief organizations into the two cities including, the Disaster and Emergency Management Authority (AFAD), the Humanitarian Relief Foundation (İHH), and the Turkish Red Crescent; the adoption of the Turkish Lira (TL); the change of school curricula; and the rename of places.

The Turkish government’s establishment of a safe zone, construction of settlements with the aim to settle millions of refugees it is planning to deport, and creation of a human shield separating it from the Kurds in Syria, confirms Türkiye’s intention to make a demographic change to the area.

Locals condemned Türkiye’s deportation of Syrians to areas whose original people living in makeshift camps and struggling to secure life basics. Kulstan Afdaki, an activist and member of the Syrian Women’s Council, elaborated on the challenges locals are facing saying:

“The biggest challenge is their inability to return to their original areas and homes or to adapt to their new areas. However, the challenges in IDP camps are more severe, since these camps lack the necessities of life and are not recognized or supported by UN bodies and international organizations.”

Only a few of the area’s original people managed to return while the homes left by them were settled by families came from different Syrian provinces including, Homs, Hama, and Idlib, families of foreign nationalities such as the Iraqis, and families of fighters of the armed factions that fought alongside Türkiye.

Much of the area remains volatile and insecure due to the constant clashes between armed factions fighting over influence and resources and the human rights violations they are committing including, killing, arbitrary arrest, torture, and the seizure of private and public property, which prevent the return of the original people.

The aforementioned violations go against the 4th item of the U.S.-Türkiye ceasefire agreement which states:

“The two countries reiterate their pledge to uphold human life, human rights, and the protection of religious and ethnic communities.”

Ahed Hendi, a political analyst based in Washington, D.C., points out that Türkiye and allied militias are the primarily responsible for implementing the terms of the agreement and went on to say:

“The displaced cannot return as long as many armed groups are fighting over the distribution of the locals’ seized property. Additionally, those groups have not yet been able to form a governing body able to achieve genuine stability that makes people feel like living in a state of institutions. The militant state is still prevailing; the area is contested between dozens of militias who do not have a true ruling doctrine but share the hunger for power, money, weapons, and civilian property.”

This joint report between STJ and Synergy aims to highlight the events preceding and after the implementation of the Türkiye-U.S. and the Türkiye-Russia agreements on Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî, the role of international actors in them and the human rights violations they caused to the victims on their displacement ways and at final destinations.

The present report centers on the current condition of the displaced, especially those in IDP camps and makeshift shelters, and on the human rights violations – mainly those related to housing, land, and property rights – committed in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî by the controlling armed factions. The report will also focus on the difficulties the displaced are facing and the impediments to their return and will make recommendations that may mitigate the effects of the two agreements on them and suggest solutions to prevent the further radicalization of the demographic change.

The present report is the third in a series of reports discussing the effects of international agreements that led to mass displacements and thus to demographic changes in Syria.[2]

The report is based on the outcomes of a dialogue session held on 5 and 6 May 2023, attended by locals and activists from Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî.

The session discussed the background, implementation, and effects of the Türkiye-U.S. and the Türkiye-Russia agreements and made related recommendations.

For the purpose of this report, we conducted online interviews with locals of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî, residing inside Syria and abroad, officials in IDP camps, writers, and political analysts. Notably, during the witness selection process we took into account the rich racial, ethnic, and religious diversity of the area. The report is also based on legal research and reports as well as news articles from reliable open sources.

Syria’s northeast has never been at peace after Türkiye’s offensive of 9 October 2019, launched under the pretext of security fears over the presence of Kurdish forces at its southern borders and its will to establish a “safe zone”.

In this vein, Amnesty International stated that during the offensive into northeast Syria Türkiye and allied Syrian armed groups carried out serious violations and war crimes, including summary killings and unlawful attacks that have killed and injured civilians, among whom was the prominent Syrian-Kurdish female politician, Hevrin Khalaf. According to local and international organizations, these violations continued unabated along with the Turkish bombardments on civilians.

After the area extending from Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê to Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî went under Türkiye and its allied armed factions of the Syrian National Army (SNA), the latter partitioned spheres of influence as follows;

The Levant Front/al-Jabha al-Shamiya, the Glory Corps/Faylaq al-Majd, and Tajammu Ahrar al-Sharqiya/Gathering of Free Men of the East deployed in Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî whereas the Sultan Murad Division and the al-Hamza/al-Hamzat Division in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê, which also had a limited presence of other factions including; the Army of Islam/Jaysh al-Islam, the al-Rahman Legion/Faylaq al-Rahman, the Northern Hawks Brigade, the Mu’tasim Division, and the 20th Division.

All the abovementioned armed factions were involved in violations against the area’s original population which included the seizure and looting of private civilian houses and shops after forcing their owners out. Public properties were not spared nonetheless the factions seized the strategic grain stocks of the area’s residents and sold part to Türkiye. What is more, the Turkish-backed armed factions committed assassinations, threats, killings, kidnappings, torture, arbitrary arrests, sexual violence acts against women and girls, and acts of discrimination on ethnic grounds.

While the armed factions justified their arrests and torture against civilians by claiming them to have links with the SNA, victims confirmed that they were arrested for ransom and released under conditions to waive their properties and leave their hometowns.

Denied returning, those displaced are experiencing dire humanitarian and financial conditions, especially in the makeshift camps, which are facing shortages of water, food, and medicine and suffering vulnerable education and health infrastructure, especially in relation to persons with disabilities.

Vying over influence between the international players present in the eastern Euphrates contributed to the area’s instability. Meanwhile, the main parties to the Syrian conflict; Türkiye, Russia, and the U.S. made gains and stabilized their military balance after the military operation.

Türkiye managed to achieve its targets of; removing the Kurdish forces from its borders, constructing settlements to settle the Syrians it is planning to deport, and Turkifying the region. As for Russia, it took advantage of the Operation to enforce its military presence, especially in Qamishli/Qamishlo, where it built a base at the airport – linked to that of Hmeimim – including air defense systems and warplanes. Russia also set checkpoints throughout the whole region.

In turn, the U.S. beefed up its forces in southern rural al-Hasakah, where the oil and gas fields and wells are located, and set military posts to prevent the expansion of the Russian influence in the area.

The dialogue session that was held by STJ and Synergy with the attendance of locals and activists from Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî, came up with the recommendations below,

To the UN, U.S., and EU

- Pressure the Turkish government to confess its state of occupation in the Syrian areas it controls including Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî and thus assume its responsibilities as an occupying power in accordance with the Fourth Geneva Convention on the protection of civilians and their property.

- Impose sanctions on Syrian and expatriate individuals, factions, and entities involved in committing violations in the areas covered by the report, and designate them as terrorists in order to cut their funding off.

- Pressure the Turkish government to stop attacking infrastructures and vital facilities in Syria’s northeast since that destroys the population’s livelihoods and threatens the already vulnerable stability in the area. This shall be in parallel with calling on Türkiye to withdraw immediately from the Syrian territories, put an end to the violent acts of the armed factions it supports, hold perpetrators accountable, and redress victims.

- Pressure the Turkish government to stop using water as a weapon against Syria’s northeast population and re-pump the water of Allouk station on which the latter depend to live.

- Pressure the Turkish government to create a safe and neutral environment in the areas it occupies to ensure the voluntary and safe return of IDPs and refugees and to desist forthwith from further demographic change practices and eliminate their consequences.

- Pressure the Syrian Interim Government (SIG) and the Syrian National Coalition to take action against the SNA armed groups to rein in their ongoing human rights violations and hold those involved accountable. Failing to do this, the two entities must be sued.

- Lend every kind of support to those affected by the Turkish invasion, especially those in IDP camps, through al-Yaarubiyah/ Tal Kojar and Semalka/Fishkhabour crossings without waiting for approval from the Syrian government (GOS), since humanitarian aid is considered a life-saving necessity.

- Provide necessary support for civil society organizations and victims’ initiatives dedicated to violation documentation and relief, especially those active in Turkish-occupied areas and IDP camps.

To the GOS

- Assume its constitutional duties of protecting the integrity of the national territory and its population and thus make formal complaints with the UN to end the Turkish occupation. Notably, the GOS can resort to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to obtain a decision obligating Türkiye to end its occupation and withdraw from Syrian territories.

- Call on the international community to pressure Türkiye to immediately cease support for militias, armed groups, and individuals suspected of being involved in committing violations according to reports by local and international human rights organizations. This must be done in parallel with suspending the negotiations with Türkiye until the complete cessation of occupation and the legal termination of the unfair 1998 Adana Agreement, which Syria signed under Turkish threats.

- Offer support and help to the displaced by the Turkish invasion, especially those in camps and makeshift accommodations.

- Grant approvals to the UN and relief organizations to use al-Yaarubiyah/Tal Kojar and Semalka/Fishkhabour crossings to deliver humanitarian aid to the population of Syria’s northeast, especially IDPs from Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî and other Turkish-occupied areas.

To civil society organizations

- Document all violations by Türkiye and the armed groups it supports such as summary killing, arbitrary arrest, forced disappearance, torture, forced displacement, and violations against property and housing rights. Documentations must be shared with the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic (CoI Syria) and the International, Impartial, and Independent Mechanism – Syria (IIIM) in order to issue extensive in-depth reports on the violations in Türkiye-held Syrian areas;

- Intensify advocacy for the voices of victims of the violations committed in Turkish-occupied areas including Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî and pool efforts to draw the attention of the international community and actors in the Syrian file to these violations

- Provide every kind of assistance (legal, medical, social, psychological, and service) to those displaced from the areas covered by this report help them integrate with the host communities, and help the latter, at the same time, to accept the IDPs among them.

- Intensify awareness-raising efforts to educate IDPs on their usurped rights, especially those related to housing and property, and show them the necessity of keeping ownership documents for their properties in the Turkish-occupied areas, and help those who lost their documents obtain copies of them from the GOS institutions.

To the AANES

- Provide basic services to the IDPs in its areas, especially those in camps, ensure their basic rights, secure jobs for them, and help them adapt to the host community.

- Create the appropriate environment for the work of civil society organizations dedicated to the issues of IDPs in its areas and remove administrative and legal barriers they are facing.

Withdrawal of the U.S. troops from the northeast Syria-Türkiye borders and their concentration in the far northeast corner of Syria gave Ankara the green light for the offensive against Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî.

Ahed Hendi, a political analyst based in Washington, DC, points out that the withdrawal decision was against the Democrats’ wishes and led to the resignation of two senior Trump officials; Brett McGurk, the Special Presidential Envoy for the Global Coalition to Defeat Daesh/IS, James Mattis, Secretary of Defense. Ahed explained:

“Biden Administration has been quite critical of Trump’s partial withdrawal from northeast Syria and its consequences on the region. However, Biden today prefers to maintain the current situation to prevent further Turkish expansion in the region.”

Ahed confirmed that the U.S. presence serves the interest of the region as it prevents the Turkish expansion in the north and the regime intervention in the south.

Ahed added, “The U.S. presence in Syria, albeit small, contributes to the stability of the region that has a large number of IDPs from different Syrian parts. This presence prevents the intervention of the international players in the region and thus destabilization.”

For his part, Manahal Bareesh, a journalist and researcher, affirmed the importance of the U.S. presence and touched on its influence on the region’s security and military situations and how it contributed to shaping the map of control of the entire eastern Euphrates region. Manahal explained:

“Under a green light from Trump to Erdoğan, Türkiye launched Operation Peace Spring and took over Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî. It was not possible for the Turks to carry out such an operation without an explicit announcement from Trump. Everything that happens in the SDF areas hinges on the presence of the U.S., the power broker.”

Prior to the Operation, the Turks issued explicit threats to the region and exerted political pressure trying to force approval of the Operation until they finally obtained it from Trump, according to Manahal.

As for the GOS and Russia, they will not give Türkiye a green light for any military operation, unless it is within the areas under the U.S. influence (Meaning if you want to bother the Americans go and do it. We do not care).

The same attitude manifested by the regime in the meeting that brought together Hulusi Akar, the former Turkish defense minister, and his Syrian counterpart Ali Mahmoud Abbas in Moscow. The latter commented on the first item of the negotiations discussed the return of refugees to Syria:

“We are not interested in the return of refugees. If you feel them as burdens, launch a military operation into Qamishli, Amuda, or any other area under the U.S. influence and return the refugees there if you fail to host them.”

Shoresh Darwish, a writer and researcher, believed that today’s role of the U.S. is to guard the agreement it signed with Türkiye. Shoresh criticized the U.S. inaction toward Türkiye’s hostilities and expansion saying:

“If we concede that the U.S. contributes to the prevention of further Turkish air attacks on Syria’s northeast, we cannot ignore its silence about Türkiye’s repeated bombing and usage of drones which threaten stability within the region and put lives of civilians and SDF forces at constant risk.”

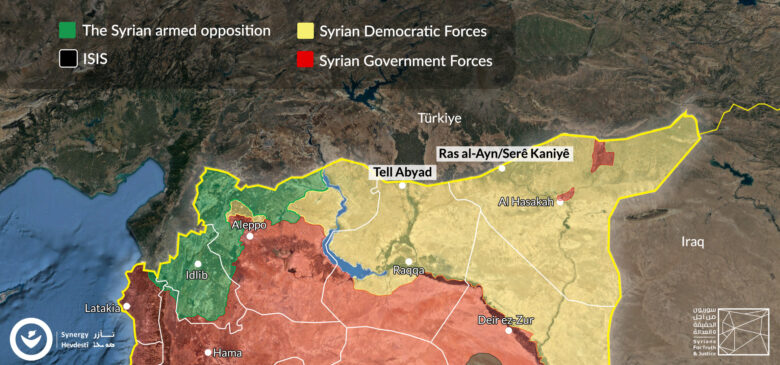

Image No. (1) – A map drawn by partners showing areas of military control in northern Syria in September 2019.

Image No. (1) – A map drawn by partners showing areas of military control in northern Syria in September 2019.

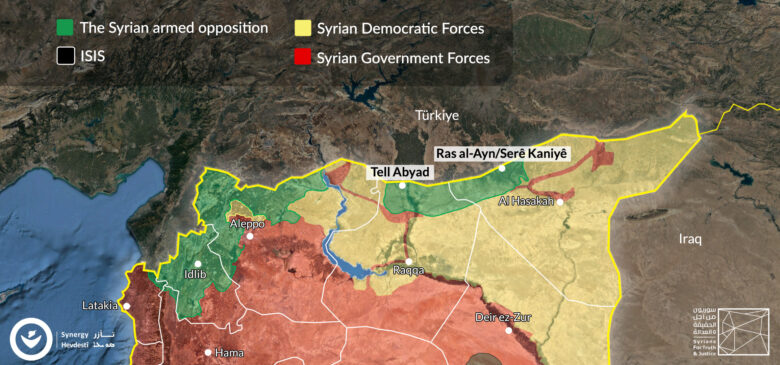

Image No. (1) – A map drawn by partners showing areas of military control in northern Syria in February 2020.

Image No. (1) – A map drawn by partners showing areas of military control in northern Syria in February 2020.

At 4 p.m. on October 9, 2019, intensive Turkish airstrikes and artillery shelling began on Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê, Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî, and the border strip separating them prompting civilians to flee to adjacent safe areas, leaving everything behind, hoping for imminent return.

According to UN figures, over 180,000 civilians, mostly women and children, were displaced from Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê, Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî during the first days of the offensive.

Hikmat Mohammad, an independent political activist from Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê described the scene of displacement saying:

“When the so-called Operation Peace Spring started at exactly 4:10 p.m. and the Turkish jets started bombing the vicinity of the city, I was at work. When I came out onto the street, I saw families with children fleeing with small bags in their hands fit only for official documents. All they wanted was to escape with their lives anywhere.”

Some displaced stayed in tents set in the open until they found shelters and others went to their relatives in safe areas not included in the Operation, such as al-Hasakah. After the end of the Operation, people displaced from Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê settled in the village of Tell Tamer, which was abandoned by our Assyrian brothers following the entry of the Daesh terrorist organization. Other IDPs dispersed to al-Hasakah cities; some of them leased houses and others resorted to schools. Later, the Serê Kaniyê/al-Talae’ and Washo Kani/al-Twaina Camps were set up and hosted about 27,000 IDPs.

Hikmat confirmed that the IDPs face myriad difficulties amide lack of support from the UN international organizations and failure of the AANES to secure basic necessities.

Ghabi (a pseudonym) a Syriac local of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê currently residing al-Hasakah after being displaced by the Operation testified:

“Most of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê Syriacs fled to villages of al-Hasakah because they are the nearest and because they have relatives, friends, and acquaintances. There was no time to flee farther. However, after things calmed down some of the displaced headed to Aleppo or Damascus but the largest part decided to travel abroad.”

Difficulties accompanied the displaced to their new destinations. Ghabi said in this regard,

“We are at a point where we suffer to secure the simplest necessities, including water, electricity, and housing. When water is pumped to us from Allouk station, we celebrate with dancing and the same goes for when the electricity is on or the aid arrives. Nonetheless, the aid we were receiving was cut off permanently recently. People of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê who were once sufficient and content ended up displaced in schools. It is a misfortune to be called displaced in your own country. Civilians always pay the heaviest price.”

According to Rayan Akhteh, the luck of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê’s Chechnya was not any better; the Turkish offensive separated their families who dispersed in al-Hasakah, Qamishli, Raqqa, Damascus, and Aleppo, and many of them immigrated since the onset of the war in Syria. Rayan recounted:

“The 2019 war left a great impact on Chechnya, which, like other components, suffered displacement which resulted in deep cracks in its structure caused, in turn, by the separation of families, displacements, and subsequent difficulties and pressures. Since starting, the Syria war impressed itself on Chechnya and affected them much, especially at the economic and living levels. As such, their youths immigrated in mass to neighboring countries and Europe and many of their families were displaced to other Syrian provinces in search of stability and safety. The war dispersed the Chechnya, which affected their social structure and culture. Chechnya almost lost the history they built over about a hundred years in the Syrian Jazira, especially in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê”

For her part, Butheina Aynder, a local of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and head of the Training, Education, and Monitoring of IDP Affairs Committee in the makeshift accommodations, confirmed that the Chechnya’s anguish is no different from that of other components. Butheina explained:

“We, Chechnya, were displaced by Russia when we demanded a ‘state’. Today we suffer displacement and its consequences. The displaced are not able to return nor to adapt to the new communities.”

According to civil activist, Julia Kurdo, most of Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî people, headed to Raqqa, Ayn Issa, and Ayn al-Arab/Kobanî. Many families lost loved ones to bombardments that also left many with permanent disabilities. Julia confirmed:

“The displaced left everything they owned behind; homes, household items, and even clothing. This made for extremely difficult living conditions, especially in cities, amid a lack of employment and a rising dollar, rent, and food prices. With this, authorities set up the Tel al-Samen camp for those who cannot afford life in cities.”

Butheina Aynder stressed the deplorable conditions gripping IDPs and the precarious situation at camps and housing centres:

“The difficulties are multiple, including inadequate access to food supplies and water, as well as a dearth of job opportunities. Additionally, there have been several tent fires that have taken a toll on IDPs. A tent was set up in the Tel al-Samen Camp to serve as a classroom to improve the poor status of education. The tent lacked safety measures and thus caught fire. A little girl died, and several others sustained serious burns.”

| IDPs at Tel al-Samen Camp, north of Raqqa, suffer in the throes of a lack of humanitarian aid and services, added to which are climate-related struggles. Because the camp is set up in a desert area, its community battles with piercing cold or extremely high temperatures. The vast majority of the camp’s population is from Tal Abyad city and its suburbs. New batches of IDPs continue to seek refuge at the camp, fleeing the recurrent Turkish shelling in the area. Most of the camp’s residents depend on seasonal occupations for a living, primarily farming and harvesting, which are limited to summers. In the winter, however, they struggle with job scarcity that aggravates their already dire conditions. Notably, Raqqa province is home to over 103,000 IDPs, dispersed across three formal camps and 58 informal ones, where they battle with abject humanitarian and social conditions due to sparse relief assistance. |

Also struggling with insufficient international support, the two camps of Washo Kani/al-Twaina and Serê Kaniyê/al-Talae’ battle with a wide range of challenges on the level of services, especially in the areas of sanitation, education, and healthcare. Moreover, the camps’ residents are threatened with fires in the summer that constantly break out due to the high temperatures and downpours in winter, which often flood their tents. The AANES largely oversees the camps because they are located inside their territory.

According to a report by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), 85 percent of the tents in northern Syria’s camps “are older than their expected lifespan and more likely to be damaged, less resistant to weather conditions and prone to leaks.”

Mohammad Hajjo, the spokesperson for the Educational Complex in the Washo Kani/al-Twaina and Serê Kaniyê/al-Talae’ Camps, described the situation in Washo Kani/al-Twaina Camp as “poor”. This reality stems from the acute shortage of essential services. He added:

“The camp is struggling with inadequate sanitation, which is leading to the proliferation of diseases and epidemics. The residents chaotically use communal restrooms with no privacy whatsoever.”

Elaborating on the daily challenges of the camp community, he added:

“The people are struggling with limited space. Every family, no matter how big or small, uses a tent that spans a few meters, which they use to eat, drink, sleep, and bathe.” Since a hard winter appears to be on the horizon, Hajjo stressed the importance of enhancing hygiene in the camp and replacing the residents old and worn-out tents.

The disadvantageous status of the camp’s residents is not limited to poor sanitation services. Families are also troubled by the various barriers hampering education. Hajjo cited a lack of support for schooling, saying the humanitarian organizations do not provide students with stationary or other learning resources, which they critically need given the parents’ harsh economic and living conditions. He demanded that concerned entities build new schools to take pressure off the crowded classrooms and improve the learning environment for the students, who remain without the bare essentials of a decent life.

Hajjo said education has recently seen a minor uptick:

“There has been a marked increase in class hours towards the end of the year. A new school was also opened in the camp, bringing the number of existing schools to three, which follow a shift-based schooling system. This has mitigated the pressure originating from the large number of students.”

In Serê Kaniyê camp, parents express dissatisfaction about the limited number of classrooms and short school time. Students at each shift are assigned only two class hours a day. Additionally, the pupils’ physical safety is compromised because the specified schooling locations are not secure.

The camp’s healthcare system is also severely lacking. IDPs, especially those with disabilities or chronic illnesses, are made to suffer further by the camp’s inadequate and limited-hour services. Dallo Mohammad Ali, the director of the healthcare office at Serê Kaniyê Camp, said:

“The situation is extremely distressing. The IRC provides its services from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. For its part, the Kurdish Red Crescent (KRC) offers emergency medical services and assistance around the clock, including childbirth care; however, this service is only available during the morning hours.”

The camp’s residents are complaining that there is no medical facility available to assist with childbirth at night. Dallo said:

“There is coordination between the KRC and the operations room in the al-Hol Hospital, under which patients who need a C-section are referred to al-Hol Camp.”

He stressed that there is no medical facility in the camp to perform elective surgeries, such as tonsillectomies, cholecystectomies, appendectomies, or hernia repairs, necessitating assigning such a facility or establishing a mini-hospital to cater to such cases. In addition to these shortages, people with disabilities and chronic illnesses are often marginalized and neglected, lacking necessary medications and specialized equipment. According to Dallo, there are 445 patients with long-term conditions and nearly 475 with impairments.

Dallo expanded on the challenges facing patients in these two categories:

“The KRC provides heart and diabetes medications, but not enough to cover the needs of the IDPs. Additionally, these medications are not offered for free at medical centers, which only makes the patients’ situation worse, especially given their limited financial resources. Moreover, the needs of persons with disabilities, including wheelchairs, continue to be unmet.”

Addressing service and aid gaps in north-eastern Syria in a 22 August 2023 report, Human Rights Watch said that “Tens of thousands of internally displaced people in overstretched camps and shelters in northeast Syria are not receiving sustained or adequate aid, thereby negatively impacting their basic rights, Human Rights Watch said today. There is an urgent need for weather-appropriate shelter, sufficient sanitation, and adequate access to food, clean drinking water, health care, and education.” The organization demanded that the UN, other aid agencies, and the autonomous administration “urgently turn their attention to the precarious humanitarian situation unfolding in informal camps and collective shelters by prioritizing a rights-based approach.”

Both Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî and Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê are hotspots for insecurity, which manifests in looting, seizures of properties owned by locals, arrests, torture, and ill-treatment. These abuses intensify the woes of the local communities, as they also struggle with deplorable services, depleted infrastructure, and high costs of living.

Hikmat Mohammad describes the situation in the shadow of the armed groups deployed across Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê as egregious. He added:

“The armed groups have dispersed within the city’s neighborhoods after they systematically looted and pillaged the locals’ properties. Moreover, each armed group has its own authorities and laws in the absence of a comprehensive legal framework. Furthermore, the city is struggling with poor healthcare services, a scarcity of jobs, and underfunding of the agricultural sector. Despite the wealth it has, the city is at its worst.”

The landscape is not that different in Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî city, according to Julia’s description. Born in the city, Julia said she had to flee her home to Raqqa in the aftermath of the Turkish incursion, adding that she never managed to return to her hometown due to the two agreements signed by Turkey, both of which were geared towards establishing their presence in the area.

Speaking about the current situation in Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî, she says:

“Locals who remained in the city are facing persecution and arrests by the SNA armed groups, in addition to the daily mental pressures, power cuts, and spiking prices of fuel and bread, lacking medical supplies and equipped hospitals.”

In her turn, journalist Shira Ousi said that only a handful of the Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê’s residents returned, adding that the returnees continue to struggle in the throes of toilsome conditions while also battling with a haunting fear of internal disputes. She also stressed that several locals were subjected to various abuses when they returned to the city only to check on their properties.

Elaborating on the situation, she added:

“All those residing in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê are exposed to hazards daily, and before anything else, they are degraded. A number of people who returned to check on their properties and memories or obtain necessary supplies to help them face the hardships of displacement were tortured, humiliated, or kidnapped for ransom. Several could not reach their homes. Those who made it back to their houses were driven out by the people who had taken them.”

In his turn, civil activist Rayan Akhteh said that even though several families did return to Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê after the Turkish hostilities abated, several other families were coerced to abandon the city for a variety of reasons, primarily: “insecurity and rampant chaos, lack of livelihoods and instability, prevalence of crimes, killing, and blackmail, demographic changes inflicted on the city’s local community, the community’s lack of access to their rights and city governance, and [non-locals’] hegemony over its administration and their tendency to impose alien trends and policies.”

Muhyiddin Isso, executive director of the DAR-Association for Victims of Forced Displacement, who hails from Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê, corroborated the abuses the SNA armed groups are perpetrating against locals. Based in Germany, he said that Türkiye is benefiting from what is happening:

“The SNA armed groups are merely tools, subservient to the Turkish occupation, and bound by their orders. They perpetrate the most heinous violations against the populace in Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî and Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê, including abduction, arrest, and torture, as well as the seizure of IDPs’ properties and denying them access to their cities, on top of which lies demographic reengineering through allowing new settlers to live within the cities and granting them homes, farms, and shops of IDPs.”

He added:

“The Turkish government can bring those armed groups into line. However, they do not wish to do so because all those crimes and violations are to their advantage.”

In a November 2019 report, Human Rights Watch said that “Executing individuals, pillaging property, and blocking displaced people from returning to their homes is damning evidence of why Turkey’s proposed ‘safe zones’ will not be safe,” adding that “contrary to Turkey’s narrative that their operation will establish a safe zone, the groups they are using to administer the territory are themselves committing abuses against civilians and discriminating on ethnic grounds.”

According to activist Gulistan A’fdeki, the Turkish government’s persistent shelling of Syrian border areas and ominous warnings of possible new incursions only serve to heighten the already palpable sense of insecurity, paralyzing fear, and inability to settle down among city dwellers and IDPs because many families had to flee their homes repeatedly.

For his part, writer and researcher Shoresh Darwish warned against the threats posed by the recurrent Turkish breaches in these areas, highlighting the dangers of the silence with which they are met. He said:

“The Turkish attacks are giving rise to significant concerns. Innocent people died in airstrikes and shelling in Tal Tamer, Ayn Issa, and Manbij, and so did IDPs. There has been no international or UN condemnation of the continuing Turkish violations. There is a kind of silence that projects a sense of normality on the Turkish shelling while it drives the residents under attack to leave their homes and abandon their properties in search of safe refuge—even though the majority are poverty-stricken—or to remain in the area and bear the consequences of their stay.”

| In their June 2023 report, the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic covered SNA-held areas, including Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî, and “found that in the context of detention, the SNA committed war crimes of torture and cruel treatment, hostage-taking, rape and sexual violence, as well as acts tantamount to enforced disappearances.” “Amongst the victims in particular are those suspected of ties to the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG)95 or SDF. Detainees – primarily of Kurdish origin – were interrogated about their faith and ethnicity and denied food or water.” |

After they controlled Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî and Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê, the SNA armed groups began seizing the properties of civilians who escaped hostilities. They transformed those properties into military centers or used them to house the families of their fighters. In some cases, the armed groups forced residents to abandon their properties using threats, extortion, kidnapping, killing, arrest, and torture—a practice corroborated by rights organizations and several locals.

Muhyiddin narrated:

“After the Turkish occupation of the city in 2019, three homes owned by my family in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê were seized. In June 2020, the İHH transformed one of the homes into a Quran institute. The governor of Urfa inaugurated the institute in a ceremony live-streamed by the media.”

He added:

“Türkiye and affiliated armed groups do not need a pretext to expropriate civilian homes in the occupied areas, where they are perpetrating violations against everything, animate and inanimate. They consider those areas and civilian properties as spoils of war to prevent the locals from returning to their city and alter the region’s demographic makeup.”

Addressing the locals’ inability to reclaim their properties, he said:

“No civilian can restore their confiscated properties because they are not allowing them to return to their cities. Through the media and local and international organizations, we attempted to expose the systematic policy of the forcible seizures of displaced people’s properties and to channel the voices of those people to international organizations to exert pressure on the Turkish government as an occupying power. However, unfortunately, my family’s house—like numerous other properties owned by people forcibly displaced from Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê—remains seized by the Turkish relief organization, which refuses to leave it.”

For his part, researcher and academician Dr. Ibrahim Muslim recounted what happened to his family home in Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî after the Turkish military and SNA armed groups entered the city:

“In October 2019, my family fled Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî. When my father first resisted leaving the home, I was concerned he would be detained like many others. He eventually left the house and everything in it in the care of the family that owned the shop directly across from us. Three months later, the family told my father they could not keep the house because an Iraqi family, who escaped Ayn Issa, asked to reside there.”

He added:

“In early 2020, the local council issued orders that the house belonged to an Iraqi family. We asked the family to take care of the house and its contents. However, we heard that they sold many of our belongings. My father was extremely agonized, got suddenly ill, and died.”

He added:

“Since then, we have not contacted anyone to inquire about our house. Nevertheless, less than seven months ago, two local council members offered to buy the house from my brother for a lucrative sum. We decided against the sale, hoping that one day we would be able to return to Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî.”

Ibrahim said that the homes of all those displaced from Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî are now at the disposal of the local council, formed after Türkiye entered the area. He added that the council is now giving away homes to families other than their owners. This applies to groves, which are also under the control of the local and military councils. They are distributing them to nonowners while making money off of their yield.

Similar property seizures in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê were corroborated by Rayan Akhteh. He said that armed groups and civilians who fluxed into the city are seizing homes, shops, and groves of locals, emphasizing that several locals who chose to remain in the city were forced to pay money in return for staying in their homes or reclaiming their groves, which is a form of blackmail and display of hegemony. He added that other displaced locals were also asked to pay money in exchange for the protection of their properties until they could return to the area.

For his part, Ghabi said that his properties in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê are intact; however, the current situation in the city still makes the return challenging:

“I do possess a real property status statement, title deeds, and identification documents. Additionally, everything still exists, including properties, groves, and machinery. Nonetheless, all the factors playing into the current situation are not conducive to returning to the area.”

It is legally inadmissible to attribute the description “agreements” to the illegitimate understandings between Türkiye and Russia on the one hand and Türkiye and the U.S. on the other, which led to Turkey’s invasion and subsequent occupation of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî. The unlawful status of such characterization originates from the fact that the object of these understandings is a territory of another State, Syria, which was neither a party to the understandings nor consented to their consequences later. On the contrary, Syria demanded that Türkiye withdraw from its territories as a condition for restoring severed ties.

Moreover, the Syrian Constitution mandates the enforcement of any Syrian State-related agreements, whether bilateral or collective, to be ratified and approved by the Syrian People’s Assembly (Parliament).[3] At odds with this, the understandings or settlements subject to this report have not been brought before the Syrian Parliament, nor have they been ratified or approved. Therefore, these agreements cannot be invoked against the Syrian State and remain legally nonbinding to the Syrian people, who thus are not obliged to endure the consequences of settlements and bargains that they did not know existed and were not informed of either directly or indirectly, through their parliamentary “representatives”. Consequently, these agreements are nearly void, and the States involved in them must fulfill their duties and re-establish the status quo ante, which prevailed before the occupation that resulted from the settlements themselves.

Because the Turkish State did not subsequently recognize that it was an Occupying Power and did not, as a result, comply with its obligations under the Fourth Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War of 1949, a state of chaos and insecurity ensued in the region, warranting numerous violations against the civilian population and communities by the SNA armed groups—effectively controlled by the Turkish Government. The violations included extrajudicial killings, arbitrary arrests, enforced disappearances, torture, forced displacement, looting, and confiscation of property, among other abuses and crimes that accompanied or followed military operations. Notably, these abuses may amount to war crimes or crimes against humanity, requiring States involved in the said understandings to act to stop such beaches and promptly hold those engaged in them accountable.

The Turkish State’s evasion of the proper characterization of the legal status of its presence in the so-called Peace Spring strip as a state of occupation does not exempt it from its legal responsibilities since the applicability of the international law of occupation is not subject to the Occupying Power’s recognition or justification of its existence, intervention, or control.[4] Given the customary nature of the provisions of international law defining occupation,[5] it is established that “in international law, as reflected in Article 42 of the Regulations Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land annexed to the Fourth Hague Convention of 18 October 1907, territory is considered to be occupied when it is actually placed under the authority of the hostile army, and the occupation extends only to the territory where such authority has been established and can be exercised.”[6] Therefore, the conclusion that the force on the territory of another State is an Occupying Power rests not only on the extent of the military deployment of that force—which can be concentrated in specific locations—but rather on its establishment and exercise of authority over the areas in which it has intervened.

Even though international humanitarian law establishes the obligation of all parties to the conflict to protect civilians in all circumstances and regardless of the nature of the armed conflict, it imposes on the Occupying Power additional layers of protection and guarantees to civilians because occupation is deemed an assault on the sovereignty of another State and must be a temporary situation. Therefore, the Occupying Power should not make changes that would actually affect this situation. Accordingly, the Turkish State is bound by all the guarantees of protection inscribed into the provisions of international law in addition to its other duties as an Occupying Power.

Examining the course of events in the so-called Peace Spring strip since the start of the Turkish hostilities, it becomes clear that the provisions of international law have been neglected, particularly concerning preventing the displacement of the civilian population. Instead, the parties to the conflict should have refrained from directly targeting the civilian population and civilian objects pursuant to the principle of discrimination, which is a rule of customary international humanitarian law. One purpose of this duty—adhering to the principle of discrimination—is to avert the displacement of civilian populations as an element of civilian protection from the effects of armed conflict. During hostilities, civilians are expected to flee in pursuit of safety. Nevertheless, this prospective response on the part of civilians does not exempt the parties in the conflict of their legal responsibilities, nor should it establish escape as a permanent reality. The parties to the conflict must take the necessary precautions before launching a military attack, including ensuring the safe and temporary evacuation of the population if there is no other option due to compelling military necessity or inability to guarantee the security of the concerned community.

Compared to the trajectory of Operation Peace Spring, there appears to be a blatant lack of precautions to spare the populace the repercussions of military activities that did not aim at specific military objectives. Additionally, the Turkish military took no measures to ensure the safe and temporary evacuation of the population until the purported imperative military necessity had ended. At odds with their obligations, the Turkish military used direct force to coerce civilians to leave against their will and without a genuine choice—which is the essence of the concept of forced displacement as established in the jurisprudence of international courts. Notably, eviction measures permitted under international humanitarian law must be in the best interests of the civilian population.[7]

In addition to the fact that the prohibition of forced displacement is established as a rule of customary international humanitarian law, the authorities in question must also abide by a number of legal obligations and guarantees when dealing with forcibly displaced people, both during and after their displacement. Humane treatment and protection of the property of forcibly displaced persons are primary subjects of several of these duties and guarantees.

Since evacuation of the civilian population—when in their best interest—is supposed to be temporary, the Occupying Power should relocate and settle civilians in secure centers, particularly within the occupied areas. Prioritizing relocation within the occupied territories offers higher guarantee to civilians’ return after the reasons that led to their evacuation have ceased to exist,[8] and also enables the Occupying Power to meet other obligations established in paragraph three of Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which states: “The Occupying Power undertaking such transfers or evacuations shall ensure, to the greatest practicable extent, that proper accommodation is provided to receive the protected persons, that the removals are effected in satisfactory conditions of hygiene, health, safety, and nutrition, and that members of the same family are not separated.”

Notably, the displacement of the civilian population that resulted from the Turkish incursion and the following practice amounting to a systematic direct or indirect prohibition of their return demonstrate that the Turkish Occupying Power deliberately transferred the civilian population from the areas it occupied. The transfers are a clear violation of paragraph one of Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention. The article is also a reflection of customary international law.

Concerning property rights, respect for the property rights of displaced persons is a rule of customary international humanitarian law. Respect for such rights is applicable under occupation, as inscribed in Article 46 of the Hague Regulations, which requires the Occupying Power to respect private property and prevent its confiscation. Preventing the original owner from exercising his or her natural property rights, including access to and entry into the property, is a form of loss for the benefit of the party restricting their rights. International humanitarian law has paid attention to potential agreements or arrangements with the authorities of the occupied territories by the Occupying Power as an effective means through which the Occupying Power can try to free itself from the obligations imposed on it by the occupation law.[9] Article 47 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, therefore, provides that: “Protected persons who are in occupied territory shall not be deprived, in any case or in any manner whatsoever, of the benefits of the present Convention by any change introduced, as the result of the occupation of a territory, into the institutions or government of the said territory, nor by any agreement concluded between the authorities of the occupied territories and the Occupying Power, nor by any annexation by the latter of the whole or part of the occupied territory.” Accordingly, any arrangements imposed or agreed upon by the Occupying Power with any local authorities in the occupied territories cannot justify the violation of the rights of the inhabitants of those territories, nor can they justify the abuse and exclusion of national law and official institutions and procedures that the Occupying Power is prohibited from altering, except to the extent that they may be in the interest of the civilian population.

Moreover, the fact that camps designated for forcibly displaced persons are located outside the territories of the Turkish occupation does not absolve Turkey, as an Occupying Power, of its legal obligations as the instigator of displacement in the first place. Despite this, the rest of the relevant parties, primarily the AANES, as the body exercising effective control over these camps, remain obliged to ensure the humanitarian needs of the forcibly displaced, particularly by facilitating humanitarian access and cooperation with humanitarian actors locally and internationally. This has been established in Principle 3 of the Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, stating that: “[n]ational authorities have the primary duty and responsibility to provide protection and humanitarian assistance to internally displaced persons within their jurisdiction.” The principle stresses that “[i]nternally displaced persons have the right to request and to receive protection and humanitarian assistance from these authorities. They shall not be persecuted or punished for making such a request.”

Given the adverse impact the Türkiye-U.S. and the Türkiye-Russia agreements continue to have on the lives of local communities in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî, the conditions for the return of displaced civilians to their home areas remain unmet under existing circumstances—especially in the absence of a safe and neutral environment and facilitatory confidence-building procedures relating to accountability measures against those involved in the civilian calamity and the restoration of rights to their lawful owners.

Muhyiddin Isso, executive director of the DAR-Association for Victims of Forced Displacement, believes that the effects of an international agreement can be undone only by another. Because such an agreement does not appear to be on the horizon, the plight of the forcibly displaced is prone to continue.

However, to mitigate the dire consequences of the two agreements, Muhyiddin necessitates that civil organizations resort to advocacy to channel the voices of the forcibly displaced to governments and international organizations and urge the provision of aid to displaced communities, especially those living in camps and makeshift housing centers. Additionally, he says that these organizations should also pressure the international community to pave the path for the safe, voluntary, and dignified return of the displaced, support their efforts to reclaim their seized properties, and hold perpetrators of these violations and crimes accountable. Such measures, he is convinced, must follow the removal of armed groups from cities and towns to guarantee the safety of returnees and ensure that they are not exposed to violations.

Like Muhyiddin, the independent political activist Hikamt Mohammad places stress on the removal of armed groups from Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî as a condition for the return of the displaced, in addition to the establishment of a civil administration from the local community and ensuring the safe return of the forcibly displaced under the auspices of the UN until a comprehensive political solution in Syria has materialized.

For her part, Butheina Aynder, the official of the Training, Education, and Monitoring of IDP Affairs Committee, underscored the vitality of providing IDPs with humanitarian aid and improving their living conditions while waiting to return to their home areas.

Journalist Shira Ousi, in her turn, said it is imperative for the key countries in the area, notably Russia and the U.S., to press the Turkish government into withdrawing from the territories it occupied. She also stressed the importance of intensifying efforts to convey the suffering of locals and IDPs to the Security Council and relevant rights groups.

[1] On 2 June 2022, the IHH transferred 139 Iraqi families from Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî to Türkiye, with the aim of returning them to their country. This was in coordination with the Iraqi Consulate in Türkiye’s Gaziantep and the Iraqi Displaced and Expatriate Office in Istanbul. 131 of the families were residing Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê. Notably, this was the second time for the IHH to transfer Iraqi families from the “Peace Spring” areas to Turkish territory, as it had previously transferred 57 Iraqi families from the area in September 2021.

[2] The first report reflected on the Afrin-Eastern Ghouta swap agreement and the second addressed the Four Towns Agreement.

[3] See Article 75 of the 2012 Syrian Constitution, available at: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/91436/106031/F-931434246/constitution2.pdf

[4] Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Uganda, Judgment, ICJ Reports 2005, p. 168, paras. 78,91.

[5] Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (Advisory Opinion), ICJ Reports 2004, p. 136, para. 89.

[6] Democratic Republic of the Congo v. Uganda, Judgment, ICJ Reports 2005, p. 168, paras. 78,91.

[7] ICRC, Commentary on Geneva Convention IV relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War (1958 edition), p. 280.

[8] Ibid.

[9] ICRC, Commentary on Geneva Convention IV relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War (1958 edition), p. 274.