Executive Summary

Hostilities forced Samar al-Hasan, 40, and her family to flee their home in Ma’arrat al-Nu’man city and settle in a makeshift camp in Harem city, within rural Idlib province. Before the family fled, Samar’s husband was killed in a regime rocket attack on their neighborhood. Now, Samar lives with her children in her family’s tent, unable to afford taking care of her children or herself without help. One source of her financial troubles is the Syrian government’s refusal to give Samar her husband’s death statement, a document which would allow her and her children to access her husband’s will. The wrinkles on Samar’s forehead speak of her suffering since her husband’s death in 2018. Even as she wistfully recalls for Syrians for Truth and Justice the comfortable years she spent in Ma’arrat al-Nu’man with her husband, she knows they will never return.

A “death statement” formally documents the death of a person. Obtaining a death statement allows a widow to remarry – if she wishes – after the passage of her “Iddah”.[1] A death statement is also required to initiate a ‘determination of heirship’ procedure by the deceased’s heirs (incl. the wife, children, parents, and siblings).

In Syria, “death statements” are distinct from “death certificates”. A death certificate is the document that confirms the occurrence of death, issued by the responsible local authorities or the institution in which the death took place, such as hospitals and prisons, or by the “Mukhtar” – the village or district chief, who keeps a local civil registry. In contrast, a death statement is a legal document issued by the Civil Registry office, where the deceased’s records are kept, after recording the death on the basis of the submitted death certificate.

The Syrian government institutions, who are legally and officially authorized to issue death documents have been using death statements to blackmail the families of deceased Syrians emotionally and financially, especially those who were killed by the regime, died in detention, or perished in opposition-held areas. The Syrian government practices a similar double standard when handling the bodies of the deceased, discriminating on the basis of the deceased’s affiliation and the circumstances of their death. The government quickly and easily returns the bodies of those who die for the regime, while burying the bodies of those who are accused of opposing the regime and die in government prisons – naturally or under torture – in unmarked, and often unidentified, mass graves.

The head of the Civil Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Interior in Syria, Ahmed Rahal, stated on 8 August 2018 that the Syrian government documented 32,000 deaths between January and August 2018, and 68,000 deaths in 2017. Rahal confirmed that the Directorate registers deaths without inspecting their causes and circumstances. Later, on 14 November 2020, Ahmed Rahal gave an additional statement in which he declared the registration of 47,000 deaths throughout 2019, and more than 35,000 deaths from the beginning of 2020 until September the same year.

With the rising death toll in Syria, STJ believes that an accurate, transparent, and non-discriminatory approach must be adopted by the State when issuing death statements and certificates without hiding or altering the truth. The families of deceased Syrians should not be forced to choose between receiving a falsified, untrue, or incomplete death document or not receiving one at all.

STJ calls upon the Syrian government to issue death statements for all dead persons including those killed inside and outside its prisons. The Syrian government must provide the families of those who are already listed as dead in the Civil Registry with death statements and disclose the circumstances of their deaths occurring within its custody, without concealing the crimes and violations against them. Furthermore, the international community should also pressure the Syrian regime to open its prisons and detention centers to the UN as well as other concerned international human rights and humanitarian organizations to properly identify detainees, stop torture and executions, and end enforced disappearances in Syria.

Methodology and Challenges

The following report is the result of STJ’s pursuit documenting the struggle of particular Syrian communities to obtain death statements for their loved ones – an issue we have been monitoring since 2011. We support our research with statements from the relatives of missing and forcibly disappeared people from the provinces of Dara’a, Hama, Idlib, As Suwayda, Damascus, and al-Qunaitra. The majority of the witnesses we interviewed confirmed that the Syrian authorities refused to issue them death statements for their dead. The government does not declare the deaths which occur in its jails and conceals the bodies of those who die or are killed there, burying the bodies of the detainees in mass graves along with the truth of their death. Authorities refuse to inform the families of the deceased where their graves are and provide no information about the circumstances of their loved one’s death, which is often brought on by systematic torture, starvation, and deadly diseases spread inside Syrian detention centers.

This paper reflects on the Syrian government’s refusal to issue death statements to certain people who died during the war, and highlights the impact of this arbitrary act on the families of the deceased. Without confirming the death status and obtaining official death statements, families are unable to move forward not only emotionally, but legally. For example, we highlight the cases of women who find themselves in a particularly vulnerable position after being denied their husband’s death statement, often being denied access to their husband’s will or being unable to marry again.

STJ’s field researchers faced numerous challenges while collecting the information and the testimonies recorded in this paper, among them the tense security situation across Syria, in addition to the Covid-19 crisis and the subsequent restrictions imposed on some of the targeted regions, all of which limited the movement of the team.

Introduction

This paper underlines why families need to obtain documents proving the death of their loved ones. The failure to access a death statement affects:

- The deceased’s wife: if she wishes to remarry, Syrian law requires the widow to present a death statement to the sharia court after the passage of her “Iddah” (restricted by Article 123 of the Syrian Law of Personal Status to four months and ten days based on Islamic Law).[2] Additionally, the wife is required to conduct the dissolution of the marriage transaction, legally termed as the break-up of a marital union, at the Civil Registry where her records are kept.

- The deceased’s heirs: the Syrian Law of Personal Status of 1953 states that those entitled to inherit the property of the deceased are his sons and daughters, wife/wives, and parents. In the event the deceased has no children, the inheritance passes down to his wife/wives, parents, brothers, and sisters. The heirs cannot initiate the “determination of heirship” procedure without obtaining a death statement for the deceased. Consequently, they cannot access the deceased’s estate, including his money, real estate, vehicles, and pension.

Syria needs an inclusive, accurate, and non-discriminatory approach when issuing death certificates and death statements; however, today how an individual dies determines whether their family receives a death statement or not. Since the war began, concealing the true circumstances of an individual’s death has become a requirement for receiving a death document. Several witnesses confirmed to STJ that competent Syrian authorities required them to sign papers claiming that terrorist groups were responsible for killing their loved ones rather than the Syrian government. After most of the deceased’s families refused, they were denied death documents.

The Syrian uprising led to the death of thousands throughout Syria. Many were killed while taking part in peaceful protests and the military operations which followed, and others while in custody. In order to accurately record how they died and where they were buried, as well as provide their families some measure of justice and peace, STJ recommends:

Recommendations

- To call on the UN Security Council to push for a radical political solution in Syria. The Security Council must ensure a transition to a democratic system that involves all Syrians and respects UN decisions while pursuing accountability and truth-seeking processes.

- To bring the army and the security services under the full authority of the Syrian constitution and law, and ensure they are subjected to judicial scrutiny, as well as that of the incoming elected government, which is meant to both exercise authority and be accountable to the Syrian people through Parliament.

- To compel require the Syrian government to issue death statements for all Syrians who died in its prisons or in hostilities, without obscuring the true cause of their death or any human rights violations they may have suffered.

- To pressure the Syrian authorities to open its prisons and detention centers to the UN as well as other concerned international human rights and humanitarian organizations to properly identify detainees, stop torture and executions, and end enforced disappearances in Syria.

- To compel the Syrian government to disclose the location of the burial sites of those who died within its custody to their families and allow those families to retrieve their dead’s remains and rebury them in accordance with the customs and precepts of their religions.

How People Died During the Syrian War

Hundreds of thousands of Syrians have died during the ongoing Syrian conflict at the hands of varying perpetrators and circumstances, complicating the procedures of issuing death documents. However, as the Syrian government is the only party legally authorized to issue official papers, it has refrained from giving death documents to families whose loved ones were killed by it, or who died while fighting for other parties to the conflict. Refusing to issue needed death documents to the families of its victims or opposing parties, the government has the power to not only humiliate the families, but blackmail them emotionally and financially.

Syrians Denied Liberties, Lives, and Futures

While freedom is a natural law which cannot be modified, repealed, or restrained by humans, it is not absolute. States maintain their people’s freedoms within a legal framework. This provides state authorities with the power to deprive a person who commits a crime from his/her liberty. However, holding a person arbitrarily constitutes a violation to domestic and international laws. When authorities conceal the whereabouts of the people they arrest, or deny holding them in custody, it constitutes the crime of ‘Enforced Disappearance’ according to the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance.

Before 2018, government hospitals, including the military hospitals of 601, Tishreen, and Harasta, issued death certificates for people who died in them. However, those certificates, though official, were not admitted at governmental institutions, which only recognize death certificates issued by Civil Registries.

As of January 2018, the Civil Registry departments in Syria began updating the data of thousands of people who died in Syrian detention centers. STJ monitored the process closely and prepared several reports on the subject. Our first report, published 18 June 2019,[3] revealed that at least 700 death certificates had been received by the Civil Registry departments in the province of Hama in early 2019. The second report, published 1 February 2021, unveiled the secret issuance and registration of tens of death certificates for detainees held by the Syrian security services.[4]

Families often learned about the deaths of their detained loved ones accidently from employees while conducting regular transactions at Civil Registry departments. However, Syrian authorities refused to grant those families death statements for their dead. One of those family members, Ahmed al-Hamwi, 60, learned about his son’s death from an employee at the Civil Registry of Hama but is still unable to obtain a death statement for him. Ahmed told STJ in January 2021:

“A military checkpoint of the Syrian security services arrested my son, 23, on 11 September 2013. He was on his way from Hirbnafsah town, southern Hama, to Hama city to buy tires for our car. Soldiers at the checkpoint took him to an unknown destination. We could not learn his whereabouts or fate. In 2019, I was summoned to the Civil Registry of Hama, where I was told that my son had died in prison of a heart attack.”

The head of the Civil Registry of Hama gave Ahmed his son’s ID card after verbally informing him about his son’s death. Ahmed added:

“On 27 May 2019, I received a phone call from someone telling me to go to the Civil Registry department in Hama. I went there the next morning and waited for two hours to meet the head of the department. The head asked me to have a seat and started talking generally about my son until he reached the news of his death and uttered words that I will remember for the rest of my life. He said that my son died of a heart attack that struck him in prison. However, he did not mention the name of the prison, the date of my son’s death, nor the place of his burial.”

Shocked by the news, Ahmed al-Hamwi did not think then about requesting a death statement for his son. Later, he returned to the Civil Registry department after his son’s condolence ceremony to request a statement. However, he was surprised to discover that this simple request would become an insurmountable challenge:

“I met the head of the department and asked him to grant me a death statement for my deceased son. I was shocked by his response. He said that he did not know my son and did not know anything about what I was saying. I tried to remind him about our last meeting 10 days ago and showed him my son’s ID card, which he gave me, but he continued denying seeing me before or knowing anything about my son. I asked him: ‘why don’t you give me a death statement as long as you are sure that my son died naturally?’ He responded by telling me to leave his office.”

Not only did Ahmed al-Hamwi fail to obtain a death statement for his son who mysteriously passed away in one of the government’s detention centers, he was not allowed to retrieve his son’s body or investigate how he died. Ahmed added:

“After I left the head’s office, I walked from one room to another in the Civil Registry telling my story to the employees there in the hope they would help me get a death statement for my deceased son, but it was in vain. After I exited the Civil Registry, one of the employees followed me outside. He told me that the Civil Registry does not issue death statements for those who died in detention centers, on instructions from security services, and that I was asking for the impossible. He said that many others were verbally informed of the deaths of their sons in prison, and were not given their bodies nor death statements – bearing official stamps – for them.”

Ahmed al-Hamwi still refuses to believe that his son has passed away. He and his family are living in the hope that they will meet him someday.

Ahmed’s case is similar to Razan Moussa’s, 26, from al-Qunaitra, who failed to obtain a death statement for her husband. Razan’s husband died in a government-run detention center in 2015. Razan told STJ in December 2020:

“My husband was arrested by the Syrian security services in 2014 while attempting to cross the border into Lebanon illegally to seek work there. We tracked his whereabouts through a military mediator in Damascus, who informed us of his death in prison in 2015.”

Five years later, Razan wanted to remarry and travel. However, the registration of her new marriage required proof of her former husband’s death. She explained:

“In early 2020, I hired a lawyer to register the death of my former husband and thus obtain a death statement for him, so that I could register my new marriage. But that did not work out. The lawyer told me that it is not easy to obtain a death certification for my former husband since his death was unnatural. Consequently, the Civil Registry did not recognize the death of my former husband and the Syariah Court refused to dissolve my former marriage.”

Unlike Razan, one wife of a detainee who died in a government-run detention center managed to obtain a death certificate and statement for her husband by bribing employees in both a funeral home and the Civil Registry. STJ met the wife, who hails from the province of As Suwayda, in January 2021. She recalled the arrest of her husband, who participated in the peaceful protest movement in Damascus at the beginning of the Syrian conflict, saying:

“My husband was wanted by Syrian security forces for his opposition political activities. He was arrested in al-Mazzeh in November 2012. Since then, we have searched for him everywhere, including in security branches, who did not provide any information related to him and even denied any link at all to his arrest. We turned to many people for help, including the Sheikh Aql of the Druze, to mediate between us and the security services to know the whereabouts of my husband, but to no avail.”

The witness did not receive any information related to her husband’s fate until mid-2013, when a survivor from Branch 285, also known as al-Khatib Branch, told her that her husband had been his fellow inmate. Later that same year, on 24 August, the wife received a note from the Military Police Branch of Damascus instructing her to retrieve her husband’s body from Damascus Hospital.

“The note I received said that my husband died in June 2013 while detained at Branch 285 of the general intelligence. I immediately went to Damascus Hospital – as I was told by the note – but did not find my husband’s body nor a death certificate nor any other paper proving his death. I only found his name listed with five others as dead in the hospital records. An employee in the mortuary room told me that my husband died of a sudden cardiac arrest. He said that they bury corpses coming from the prisons in mass graves after they reach a certain number in the hospital mortuary.”

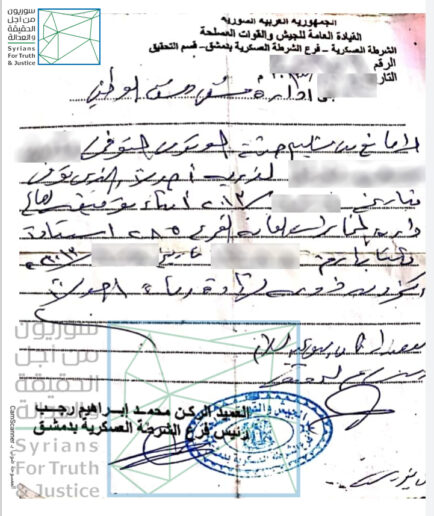

A formal written note directed from the Military Police Branch to Damascus Hospital allowing the surrender of the body of a man who died while incarcerated in General Intelligence’s Branch 285 to his family. Credit: STJ.

Afterwards, the husband’s family tried to obtain an official document proving the death of their son. Both the hospital and the Civil Registry refused to issue them such a document. The hospital even refused to disclose the site of the husband’s grave. The wife; however, succeeded in obtaining a death statement for her deceased husband after bribing an employee at the funeral home, allowing her to initiate a “determination of heirship” transaction:

“After my husband’s family failed to obtain a death certificate for him, I went to the funeral home and managed to obtain a death certificate for my husband by bribing an employee there, and was thus granted a death statement for him from the Civil Registry.”

However, the wife could not complete the “determination of heirship” transaction because security services summoned her to investigate how she obtained a death certificate for her deceased husband. Fearing she would suffer his fate, she fled to Lebanon with her sons and later took refuge in a European country.

The testimonies of Syrians like Ahmed al-Hamwi and Razan Moussa prove that Syrian security services do not abide by what is imposed by the Syrian Civil Code promulgated by Legislative Decree No. 26 of 2007. Article 38 of the Syrian Civil Code stipulates that deaths occurring in prisons and hospitals are registered in the Civil Registry based on death certificates issued by the heads of institutions or their deputies. Additionally, the Code’s Article 44 states that no deceased can be buried without a death certificate from a medical source and, in the event the area has no doctors and/or the cause of death is suspect, the mukhtar must collect information on the death and deliver it to the relevant judicial and administrative authorities before issuing the death certificate.

Furthermore, the Syrian security services’ failure to surrender the bodies of those who died under in custody to their relatives is only the last injustice committed against those in their jails. Detainees in security services’ prisons are killed in diverse ways, including torture, field executions, extrajudicial killings, and under execution sentences issued by exceptional courts, such as Syria’s notorious, but now inactive, Supreme State Security Court, and Syria’s still active Military Field Courts which have issued the death sentences of tens of thousands of Syrians before and after 2011. We also have evidence that security forces kill their detainees in secret collective hangings carried out under the cover of darkness. Amnesty International has reported that many detainees at Saydnaya Military Prison have been killed after being repeatedly tortured and systematically deprived of food, water, medicine, and medical care. Amnesty confirmed that the bodies of those who are killed at Saydnaya are buried in mass graves.[5]

Article 468 of the Syrian Penal Code criminalizes the violation or desecration of graves. The same article also considers it a crime to bury or cremate an individual without due process or contrary to the laws and regulations related to burial. If the burial or cremation is committed with the intention of concealing death, Syrian law states that the perpetrator should be imprisoned between two months and two years. In other words, the Syrian government’s burial of detainees contrary to religious and legal principles, as well as social customs, violates the Syrian Penal Code and constitutes a punishable criminal offence. In addition, by denying an individual the right to a proper burial and their family’s right to bid them farewell, the Syrian government also violates Article 19 of the Syrian Constitution which provides for the maintenance of human dignity for every individual.

To read the full report as a PDF, follow this link.

[1] The ‘Iddah’ is a waiting period of four months and ten days that a Muslim woman observes after the death of her husband.

[2] The amended Syrian Personal Status Law of 2020, the Syrian Lawyer Club, 15 March 2019, https://www.syrian-lawyer.club/%D9%82%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D8%AD%D9%88%D8%A7%D9%84-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B4%D8%AE%D8%B5%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AC%D8%AF%D9%8A%D8%AF-pdf/ (last accessed: 6 March 2021).

[3] New Notifications Declare Dead Hundreds in Syrian Security Services’ Detention Facilities, STJ, 18 June 2019, https://stj-sy.org/en/new-notifications-declare-dead-hundreds-in-syrian-security-services-detention-facilities/ (last accessed: 6 March 2021).

[4] “My Mother still Hopes He’s Alive”: Dozens of Syrian Families Told their Detained Loved Ones are Dead, STJ, 1 February 2021, https://stj-sy.org/en/my-mother-still-hopes-hes-alive-dozens-of-syrian-families-told-their-detained-loved-ones-are-dead/ (last accessed: 6 March 2021).

[5] Human Slaughter House: Mass Hangings and Extermination at Saydnaya Prison, Syria, 7 February 2017, https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/mde24/5415/2017/en/ (last accessed: 6 March 2021).

1 comment

[…] [xlix] Syrians for Truth & Justice, Arbitrary Deprivation of Truth and Life, (May 20, 2021), 3&5. Also available online at https://stj-sy.org/en/syria-arbitrary-deprivation-of-truth-and-life/. […]