-

Executive Summary

This report investigates the primary challenges facing Syrian women’s civil society organizations (CSOs) under the multiple authorities across north-western Syria. Building from the perspectives of women in the civic space, the report seeks to shed light on the needs of CSOs devoted to supporting and/or empowering women in the region; channel the voices of women activists struggling with a lack of rights and countless violations; list their opinions on the best mechanisms to respond to their urgent needs; and provide recommendations as to how to support their work.

For this report, Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) interviewed 19 women from various working spaces that focus on women’s affairs, including members of women’s CSOs, lawyers and legal consultants, and journalists and media workers informed of the activities of women’s organizations and feminist groups.

Based on the inputs from the interviewees, women’s CSOs in north-western Syria grapple with multiple barriers. These barriers start at the level of family and society, predominated by a mindset that fails to recognize gender equality in the workplace and other vital areas of life. Moving beyond the household and community, women also remain bound by restrictions on their mobility, dress code, and basic liberties imposed by men of religion, religious institutions, and fanatic groups in the region.

Notably, the authoritarian grip on women is not maintained only by the religious establishment and grows tighter under higher structures of power. Both the political and military authorities in the region cast a shadow on women’s presence and activities in the public sphere, threatening their civic and legal work and constraining especially endeavors aimed at women’s empowerment with stringent laws and regulations. Besides the entwined barriers posed by religious and military authorities, women’s CSOs also wrestle with funding. Saying that it continues to be the greatest challenge to overcome, the interviewees stressed the adverse impact insufficient funding has on the organizations’ work and their goal of enabling the women they support to participate in public life.

These barriers leave women’s CSOs and feminist groups in north-western Syria with a plethora of unmet basic needs, the lack of which continues to undermine their efficacy. Through an analysis of the interviewees’ statements, STJ concluded that the most urgent of these CSOs’ needs are security and protection. The respondents emphasized their need for special laws that safeguard their rights; guarantee they have equal rights with men; and also protect them from gender-based discrimination. In addition to law-backed equality, the respondents highlighted the necessity for building the capacities of women and related CSOs; and providing both women beneficiaries and employees with mental and healthcare services, and most importantly, with access to sustainable funding unbound by donor agendas.

These barriers and needs, which influence the activities of the women’s CSOs in north-western Syria, remain tightly connected to the larger context of the country. In 2023, the situation for women and girls was described as “worse than ever” as the conflict continued. Women and girls constitute around half of the 15.3 million people needing humanitarian assistance. Among these women, 4.2 million are of reproductive age. Contributing to the abject humanitarian status of these women is gender-based violence, which was pervasive throughout the year, as well as child marriage and digital violence which are on the rise.

Notably, several of the women STJ interviewed requested anonymity; they insisted that their personal information and the names of the organizations where they work be withheld for security purposes. Therefore, only the positions or professions of the respondents, as well as the specialties of their respective CSOs or groups, were cited in this report.

-

Background

Divided geographically, militarily, and politically by an over-a-decade-long conflict, Syria continues to endure a multi-layered humanitarian crisis with several abiding effects. The conflict has triggered one of the largest waves of internal displacement worldwide—over seven million people fled their original places of residence, according to UN figures. Additionally, hostilities have destroyed vital infrastructure and were accompanied by gross violations of a wide range of human rights established by international humanitarian law and international human rights law.

These repercussions have all exacerbated the suffering of the Syrian population, especially women, in the shadow of a struggling economy across the country. In 2023, while Syria was the third-least safe country universally, according to the Global Peace Index, over 15 million Syrians were registered as in need of humanitarian assistance.

While still wreaking havoc on the Syrian landscape, the war continues to have a disproportionate impact on the lives of women and girls who struggle in the throes of unabating and large-scale violence. Crimes targeting women are recurrently reported due to a lack of protection and support for the victims, but most importantly, rampant impunity and the absence of a legal framework that bans the multiple forms of aggression against women, including cyber violence.

In this hostile environment, women, especially those in the workforce or who are involved in the public scene, also wrestle with smear campaigns and threats both online and offline. At the same time, girls are still forced to drop out of school and coerced into puberty and early marriage.[1]

On top of the multiple repercussions posed by the conflict, the earthquake that hit Syria and Türkiye in February 2023 increased the population’s need for humanitarian aid and aggravated the woes of women, who have to overcome additional challenges in a high-pressure environment. The strain on women is a consequence of the vacuum left by family men—who were either killed, detained, or went missing—on the one hand, and the various controls curtailing these women’s essential liberties, including freedom of movement, access to the labor market, and the right to protection, on the other hand. These limitations derive from the ongoing hostilities as well as the normalization of gender-based violence warranted by the authorities, the religious establishment, and society at large.

| A 2023 study by the Syrian Civil Defense (White Helmets), based on interviews with 1,746 women in north-western Syria, revealed that the dire financial and living conditions in the region necessitate that women take an active part in working and supporting the household as a solution through which they can improve the realities of their families and society. However, the study showed that only 29% of the women interviewed had jobs, while the remaining 71% were unemployed. |

Notably, the several crises Syrian women struggle with today also have roots in the blatant discrimination against women in the Syrian legal frameworks, particularly the biases condoned by the Personal Status Law, the Penal Code, and the Nationality Law.[2] While these laws predate the conflict, the majority of the de facto authorities operating in various areas across the country and their affiliated legislative bodies have so far failed to seriously address discrimination against women, improve their conditions, or even legally establish and protect their rights. Women’s legal status thus remains vulnerable in opposition-held areas, despite the somehow divergent approaches to women’s needs adopted and the very modest legal reforms sought by local authorities in certain territories.

For instance, in early January 2024, the Syrian Salvation Government (SSG), affiliated with Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), issued the “Public Morals Bill.” The bill consists of 128 articles, one of which provides for establishing a “morality police.” Several activists expressed concern over the draft law that has bestowed a “legal status” on the idea of “propagation of virtue and prevention of vice,” which they believe will adversely affect already limited freedoms under the HTS’s rule.

Additionally, military operations have drastically changed the country’s control map. The alterations on the ground had a grave impact on all components of the Syrian society, giving rise to humanitarian, political, social, and civil challenges. Of the components most disadvantaged by the shifting borders of the map were CSOs, particularly women’s organizations and feminist groups.

-

Challenges Facing Women’s Organizations

Over the past five decades, the successive Syrian governments have continued to systematically marginalize women and deeply establish negative stereotypes about their social roles. To this end, authorities instrumentalized norms, customs, traditions, and religious rulings while enforcing prejudiced laws and economic policies. The situation underwent minor shifts with the start of the 2011 uprising. The nation-wide protests had a watershed effect; they created space for greater civic participation and the emergence of many women’s organizations and feminist groups, which seek to meet women’s humanitarian, social, political, and economic needs throughout the country.

During this phase in particular, women were intent on challenging society, predominated by a male-centered mindset and patriarchal powers, along with other systems of oppression and marginalization—which limit their reach to rights and freedoms; restrain their movements; and undermine their ability to work and actively partake in the various domains of life. Therefore, women managed to carve out spaces of their own and break down prevailing stereotypical patterns on the path to claiming their essential role in society and the State.

Nevertheless, on this journey of determination, women’s CSOs had various fences to break through; some were erected by the ruling powers, others by society and religious institutions. These institutions did not relent as women’s organizations also struggled to overcome funding-related challenges that play a primary role in limiting their growth and development.

-

Defenseless in the Shadow of De Facto Authorities

Two military and administrative entities share control over north-western Syria—HTS, designated as a terrorist group, and its affiliated SSG, on the one hand, and the Türkiye-backed opposition’s Syrian National Army (SNA) and its affiliated Syrian Interim Government (SIG), on the other hand.

Both groups suppress the voices of activists and ban their activities if they run against their interests, mirroring the policies of the central Syrian government. Struggling with similar restrictions, several women’s CSOs opt for secrecy or maintain a low profile, which renders their work invisible and under-documented. For insights into the repressive practices of the authorities in north-western Syria, STJ interviewed a lawyer in a law and consulting office in Idlib province. She said:

“The authorities restrict freedom of expression and association for women and girls, threatening them with violence and punishment if they do not adhere to their rules and norms. Because women lack protection from instigation in north-western Syria, women and girls are constantly exposed to hate speech, harassment, intimidation, and incitement [to violence] by the authorities, which use social media, mosques, and public spaces to spread their propaganda and ideology.”

For her part, a worker with one of the region’s organizations highlighted that the authorities’ tightening grip has forced CSOs in north-western Syria to often limit the scope of their work to supporting women without breadwinners, thus helping them to start small projects, or encouraging those with home-based craft businesses.

The restrictions at the organizational level are but one of the many factors preventing women from seeking employment or even participating in public affairs. Other factors include the authorities’ failure to meet their duty of protecting women. Several activists told STJ that they are often targets for threats due to their work. One Aleppo-based activist said:

“I went through a violent experience once while working on a project. One of the project’s beneficiaries threatened to kill me if I refused to put the name of a specific woman on the list of aid recipients. Naturally, the organization I worked for then failed to address the situation. An official complaint was filed with the administrative courts. However, it led to no action. This type of violence is recurrent, especially at the start of each project.”

In addition to verbal threats, other activists narrated their experiences with digital violence. A feminist journalist said:

“Several women activists face cyber and sexual violence, online and offline, by individuals who attempt to silence and defame them and denigrate their work. I am speaking out of a personal experience that I went through after I applied to get authorization to report on arrests against women in Afrin and the violations perpetrated by the armed groups. My application was denied, of course.

| On 26 July 2023, Front Line Defenders published a statement in solidarity with Hiba Ezzideen Al-Hajji, a woman human rights defender and CEO of the feminist organization Equity and Empowerment, who was targeted by a malicious online defamation campaign because of her work on women’s rights. The smear campaign persisted offline as well, whereby she received death threats. The organization called on de facto authorities in Idlib, namely the HTS, to stop targeting human rights defenders. |

Notably, in its June 2023 report, the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic (COI) said that “the HTS and some SNA factions have on occasion intimidated and restricted certain outreach and awareness raising activities related to violence against women, or activities addressing topics such as child and early marriage. Some women’s rights activists have faced harassment and negative speech from local religious authorities.”

Providing STJ with additional information on the practices of the SIG and affiliated entities, an Aleppo-based lawyer at a legal and Sharia consulting office said:

“The SNA does not respect the rights of women and girls and exposes them to violence, abuse, and discrimination. The SIG also imposes a conservative, patriarchal culture on women and girls and restricts their freedom and independence. Women who work in institutions and organizations that do not comply with the SIG’s or armed groups’ mandates are attacked and face accusations of terrorism, treason, or cooperation with Kurdish forces.”

As the SIG continues to force its ideology on the activities of women’s CSOs, the SSG puts massive hurdles in their path in its areas of control. Several activists and media workers talked about the difficulties CSOs face in obtaining the approvals necessary to carry out their activities. An Idlib-based activist said:

“The greatest challenge lies in applying for authorization from the HTS-affiliated SSG. The authorization is somewhat expensive for these initiatives and volunteer teams, especially at the beginning of their formation. There is also the fact that a segment of the society disapproves of women’s work and that authorities do not support women.”

It is not only the high costs of the authorization that stand between women and their jobs. Women in the media field are denied approvals because journalism is deemed a profession “unfit for women.” In a 2023 report, Al Jazeera captured the challenges facing female media workers in north-western Syria. One journalist told the channel that the authorities refused to grant her a press card because she is a freelancer. Without the card, she has to apply for the hard-to-obtain authorization for every incident she intends to write about or film. Additionally, she said that female media workers are not allowed to cover stories from shelling and clashes’ sites first-hand.

The systematic discrimination the de facto authorities practice against women in north-western Syria stretches beyond the labor market and into academia. In 2023, the SSG-affiliated Idlib University opened the Faculty of Political Science and Media. The new faculty aims to accommodate “journalists who have covered the events of the Syrian revolution since it began and who deserve to obtain an academic qualification.” However, the targeted group of activists did not include women, who were prohibited from enrolling in the new program. Justifying the ban on women’s registration, Adel Hadidi, the dean of the new faculty, told Syria Direct that women are not taken in by the university because it lacks “the necessary infrastructure to allocate a special department for women,” as the SSG prohibits mixing between sexes in all programs at Idlib University.

Additionally, the de facto authorities’ approach towards the overall needs of women, and the women’s CSOs and feminist groups in particular, only contributes to the hostile environment in the region. Rampant insecurity and lack of safety in north-western Syria—due to continued shelling and airstrikes by the Syrian government forces and the Russian military on the one hand, and the internal disputes among the factions across the region on the other hand—have forced all CSOs, especially women’s organizations, to centralize their activities around rapid response rather than long-term projects. Several activists emphasized this drawback. One of them said:

“Women’s CSOs face various challenges, including having to work during persistent shelling and displacement, which continue to destabilize their activities. Additionally, the recent earthquake had a dire impact on the activities’ sustainability. Furthermore, some of the organizations that operated in quake-hit areas lost assets and documents, while others relocated to different areas. This influenced their initiatives and outreach and forced them to start building their popular base from scratch in new places and contexts [. . .]. Also, female employees working with women’s organizations have difficulties traveling and moving around due to shelling and the spread of extremist Islamist factions that pose a barrier between women and work inside Syria.”

The hardliner groups do not only deny women access to education and hamper their work. More drastically, these armed groups’ failure to comprehend the crushing financial circumstances of women and the roles many of them had to play, against their will at times, especially those who lost their breadwinners, continues to pose a major threat to their lives. In 2022, Fatimah Abdulrahman Ismail received a bullet to the head that killed her. Fighters at an HTS-affiliated checkpoint shot and killed Fatimah, a mother of three, as she ‘smuggled fuel’ between the territories controlled by the HTS and those run by the SNA. Fatimah lost her life over only three Turkish liras she made in profits from fuel price differences between the two areas.

-

“I Had No One to Defend Me”: Women are Prey for Social Norms

In north-western Syria, women are born into a patriarchy that dictates their movements, actions, and dress code both at home and outside, thus restricting their ability to hold leadership positions and make decisions. Manifestations of the patriarchy are even observed in women’s organizations, where managerial positions are sometimes still held by men. A male-dominated workplace is warranted, especially in the total absence of gender equality, a situation that perpetuates gender-based discrimination.

| Terms and concepts, including feminism, gender sensitivity, freedom of belief, and sexual orientation/gender identity, among others, which recently have been central to civil society, including in Syria, remain frowned upon by the de facto authorities in certain territories and are most often condemned and used as a pretext to crack down on CSOs embracing the values they represent. |

Social norms undermine the status of women and devalue the efforts made to empower them. This negatively influences women’s demand for their rights and engagement with women’s and feminist civil organizations, affecting women employees and beneficiaries alike. Additionally, gender-based discrimination continues to deprive many women of their right to representation; participation in leadership roles; and access to opportunities and resources on an equal basis with men. Speaking of the challenges stemming from gender inequality, the executive director of a north-western Syria organization, which provides women relief assistance, basic services, healthcare, and psychological support while also empowering them socially, legally, and politically, said:

“The problem starts with the patriarchal ideology, which refuses to view a woman as a fully developed being or a citizen equal to men in rights and duties. For instance, many women hail from families that reject the idea of letting their female members leave the house and believe it is not a priority. Additionally, numerous families prefer that women only go outside occasionally due to rampant insecurity [ . . .]. The local community has become more accepting of the work of women’s or feminist organizations, maybe because people have observed the real benefits brought about by these organizations through providing women with job opportunities and helping them support their families financially as high rates of unemployment prevail among men across north-western Syria. However, this does not mean that society is merciful, as it accepts women in the workforce without hinting at issues such as equality or discussions about gender issues and women’s rights.”

Underscoring the statements of the above-cited interviewee about gender inequality in the workplace, a former employee with a second north-western Syria organization that supports women financially said:

“It is a common fact that our communities are largely patriarchal and lack equality between men and women; they always grant men more rights, such as higher pay [. . .]. During my work for the organization, I was treated differently from my male co-workers; I never felt my work was valued, and I struggled on every level. However, I had no one to defend or stand by me.”

Beyond workplace struggles, several activists spoke about how male family members controlled their decision to work with women’s CSOs and “how fathers and husbands have the final say as to whether their daughters or wives could go to support centers.” Notably, in north-western Syria, women’s engagement with CSOs, both as employees and beneficiaries, cannot be separated from how they interact with and in the public sphere in general. The public is a space governed by laws that are a nexus of the dictates of the family and authorities. These laws demarcate the boundaries of women’s presence and involvement in any space outside the home.

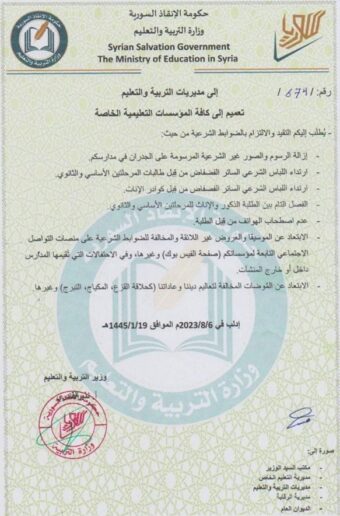

In addition to these laws, the boundaries are shaped and rendered firm by community campaigns that deny women their ability to make decisions independently. For instance, in August 2023, the SSG-affiliated Ministry of Education issued a circular demanding that all private educational centers abide by seven regulations derived from Islamic Sharia—three of these were specific to women, staff members and students. Women are obliged to stick to the Sharia-complaint dress code and wear loose-fitting and full-coverage clothes. Furthermore, women were instructed to keep away from “trends that go against the teachings of [the Islamic] religion and norms,” including wearing makeup.

Image 1-Copy of the circular issued by the SSG-affiliated education ministry in Idlib

-

“The School Director Kicked Me Out After I Refused to Wear Niqab”

In addition to the pressure imposed on women by social norms, women’s SCOs are often attacked by men of religion and imams, who condemn, in the strongest language, activists and even ideas that defy male authority. During a sermon, considered one of the reasons why assaults against women activists in Syria are condoned, Sheikh Ausama al-Rifa’i, head of the Syrian Islamic Council, said:

“In this region, there is strong mobilization by the colonialist circles—the circles of infidelity and depravity in the West, in the entire West. They have gathered armies and sent them into our countries to lead our youth astray from their morals and values [. . .]. Are you aware that there are women, who speak our language, who are actually from our country and cities, getting recruited by the UN and other centers of perversity, the centers of blasphemy and depravity? They are here to spread, especially amongst our girls, notions of what they call women’s liberation, what they call gender [. . .]”.

The religious discourse is supposed to be geared towards encouraging equality, promoting women’s rights, and supporting empowerment policies to ensure women’s participation in political, social, and economic life. Nevertheless, in reality, the religious rhetoric in north-western Syria has only had a contrary effect, adversely impacting the activities of women’s CSOs. This rhetoric represents an unremitting challenge ahead of gender equality, as Islamic scholars continue to reinforce the societal and cultural barriers women have always battled against, forcing them to succumb to traditional roles projected on them; preventing them from breaking away from dependency; and defaming any women who attempt to emancipate themselves from their pre-customized moulds. On this, an executive director of one of the CSOs operating in the region said:

“De facto authorities use religious discourse to agitate the community against women. There are restrictions on women’s mobility and dress code. Even though these controls are decreasing over time, they are still used against us. For instance, there are no hijabless women in Idlib. This is not to mention the limitations imposed on women’s work and participation in political and legal fields.”

For her part, a worker with an Aleppo countryside-based organization that offers girls’ empowerment programs said:

“We struggle with mobility, especially as transportation fares went soaring, and also due to the tight policing we are subjected to by the fighters on HTS’s military checkpoints. They constantly demand that we move around with a mahram (male companion), for society and the controlling government refuse the notion of women traveling alone regardless of what time of the days it is.”

Having a similar experience, one activist said:

“I was often harassed for not wearing Sharia-compliant clothes. When I was still teaching, the school director expelled me because I refused to wear a niqab (face cover) and abaya (long loose garment).”

In north-western Syria, bans on women’s “mixing with men” within various work domains; “traveling without a male companion”; and non-compliant dress; and accordingly, the persecution of women that do not adhere to Sharia-mandated clothes, fall under a set of Islamic Sharia rulings that control all aspects of a woman’s life. These rulings are recurrently materialized by the de facto authorities, which established several religious security services, including the HTS-founded morality police, or Jihaz al-Hisba, initially called Sawaed al-Khair (Goodwell Corps) and later Jihaz al-Falah (Salvation Service). The latter assigned itself as the “guardian of virtue” and often addressed men through public messages, which stressed their duty to protect the “honor” of women, making a direct connection between a woman’s virtue and how she dresses.

Image 2-Banner displayed by the HTS-affiliated Salqin Directorate of Endowments in Harem city, during its 2021 campaign “guardians of virtue”.

The SSG dissolved the morality police Jihaz al-Falah in late August 2021. However, in early 2023, it declared it would re-operate its Public Morality Protection Police, which will resume duties under the interior ministry.

-

“All Judges are Men”: Patriarchal Laws and Judiciary

Neither the law nor the judiciary are exceptions in north-western Syria, for both are governed by similar patriarchal power dynamics, like social norms and religious rhetoric. This was corroborated by several legal professionals, who uncovered some of the intricacies of the law enforced in the region and how it fails to bring justice to women or support them. A legal consultant who works with a humanitarian organization said:

“Theoretically, it is the Syrian government’s law that is being applied in Azaz and almost the entirety of the territories held by the SIG. In Idlib, Sharia rulings are enforced, and the application of these rulings is often bound by the whims of the official in charge of enforcing the law, namely the judge himself, with judgment affected by his familiarity with jurisprudence, knowledge, and level of commitment to remain objective. Naturally, it would have been best to regulate the applicability of the Islamic Sharia rulings rather than leave it to the judge’s discretion. This could have guaranteed that the general rulings are unified and, in turn, give similar rights to all.”

According to the above-cited COI report, of June 2023, “Widows and women in general in Idlib are not formally prevented from moving or travelling without a male mahram. One exception is however access to sharia courts in areas controlled by HTS. Physical access to these courts is conditioned on being accompanied by a male, including in courts where personal status issues such as marriage and divorce are adjudicated. The practice is also enforced in criminal courts, unless the woman herself is a defendant. As a plaintiff, she would need to be accompanied by a male relative or guardian.”

As an extension to these discriminatory and restrictive laws, the Bar Association in Idlib and its suburbs issued a circular in 2023, demanding that lawyers “refrain from meeting with female clients outside the courts without a mahram” to prevent “unwarranted mixing”. The association justified the decision, saying it was because “several lawyers have committed Sharia breaches and frequented cafes with women, who hired them without a mahram.”

In addition to their conditioned access to courts, women suffer due to the fact that “no female judges have been appointed to these courts, and female lawyers face the same challenges as other woman in terms of attending court sessions, and therefore do not represent clients in these contexts. Widows and female heads of household are also reported to face high levels of sexual harassment when trying to access other administrative or judicial procedures, ” according to the same report by the COI.

Addressing women’s presence in the judicial field, the legal consultant cited above stressed that there is a high discrepancy between female legal professionals’ access to courtrooms and the roles they are assigned in the different control areas in north-western Syria:

“In the SIG-held territories, there are female judges and lawyers. However, in the SSG-held areas, there are female lawyers only. Women do not work as judges, nor with the police or in prisons.”

For her part, a lawyer who works at a legal and Sharia consulting office in Aleppo said the lawsuits filed by women are highly taken for granted, especially since women are not assigned primary roles within the judicial system:

“The majority of women-related cases are either Sharia-based or civil, for the region is not controlled by an authority or a legal system that is founded on democracy, plurality, and equality. Also, the courts here do not respect the rule of law and human rights standards. They often neglect or reject complaints filed by women and girls. Only very few women work within the legal system in north-western Syria, and most of these are lawyers at the Sharia courts. Women are neither encouraged nor supported to take up positions as judges, lawyers, or public prosecutors because these roles are seen as unfit for women.”

Within this context, the lawyer working with the Idlib-based legal consulting office said:

“All judges are men, biased, and discriminate against women and girls. Courts do not uphold the due legal process and these girls’ and women’s right to a fair trial. They are often deprived of legal representation, evidence, and appeals. Additionally, courts make harsh and disproportionate rulings against women and girls, including lashing, stoning, or death for alleged crimes such as adultery, disobedience, or lack of compliance.”

Another lawyer who works for an Idlib-based legal organization said:

“I can say that the judiciary is fair to women only in a little over 40% of the cases in northern Syria. Of course, this is should the woman succeed in filing a complaint without facing difficulties or other barriers that force her to remain silent [. . .]. Several of my coworkers work at the courts. They are not judges. They are lawyers because the role of a judge is exclusive to men. As if a woman is an ‘awrah (an intimate part that must remain covered) and must not be a judge.”

-

“We Need Sufficient Funding that Guarantees Sustainability”

In addition to the societal, political, and religious challenges discussed above, women’s CSOs in north-western Syria also struggle with the sources of funding and the policies governing their access to the funds. Funding that is conditioned by specific donor ideologies has devastating effects on women’s organizations and feminist groups, as emphasized by several of the interviewed activists. The activists said that such conditioned funds limit the CSOs’ freedom to work on programs they believe are more effective and necessary for beneficiaries than those forced by donors. The activists added that CSOs are sometimes directed to implement projects that address unrealistic needs; do not comply with the beneficiaries’ real demands; or even fail to remedy the decades-long marginalization they have been facing.

Furthermore, several women’s groups in Syria are unable to have official registration and, accordingly, do not have bank accounts, even if they are fully active in the areas where they operate. Without registration, these groups cannot sign contracts with donors or receive the funds necessary to operate. That is not to mention that unsustainable and insufficient funding does not provide these groups with the sense of security that would drive them to pursue the projects they have planned.

Additionally, in matching observations, several activists revealed that CSOs often engage women’s organizations and even tend to increase the number of their female employees only to meet quotas and keep an appearance of gender justice to obtain funding. However, in practice, these organizations do not prioritize women’s rights.

Addressing some of the consequences of the donor policies on beneficiaries, one activist, working at a women’s vocational training center (where they learn sewing, hairdressing, and first aid), in addition to conducting several awareness-raising sessions for women, said that the number, programs, and financial capacities of women’s CSOs and feminist groups currently operating in north-western Syria are insufficient to cover the needs of women there. She added:

“The spatial distribution of these organizations causes some areas to be neglected, especially with the proliferation and emergence of several new camps. These camps were established after the earthquake in locations that are relatively remote from these organizations’ operations. Additionally, while some regions are accommodated by numerous organizations, other regions lack any organizations or have one in best-case scenarios that would have to attend to needs in a large geographical range [. . .]. We need adequate funding to ensure the continuation of work and to constantly develop team capacities through training in keeping with the requirements of our activities, working conditions, and specializations [. . .]. Furthermore, there is a need for a secure environment and also for relaxing the complicated measures of security clearance that women’s organizations have to obtain to be able to implement their projects.”

In relation to funding as well, there remains a huge gap between the concepts of equality and empowerment—the donors ask grantee organizations to incorporate into their policies—and the applicability of these concepts on the ground, given that they are rarely put into practice. One lawyer who works with a media association spoke about prevalent discrimination between men and women and how gender inequality continues to be unaddressed by several women’s organizations. She said:

“The Syrian affair has given rise to numerous societal complications, the primary victims of which are women. Therefore, UN entities and donors continue to demand the empowerment of Syrian women, whether socially or politically, and even if in a nominal manner. However, in non-governmental civil organizations, men tend to take up senior positions and are allocated the highest salaries just because they are men. As for women, they are paid poor wages. Notably, Syrian women were not given a real opportunity to participate in shaping the course of the Syrian cause. For instance, male and female workers in the majority of the organizations active in the liberated territories keep saying that women robbed men of job opportunities. Nevertheless, in reality, men, especially those living abroad, are assigned to most of the key positions. They are granted lucrative salaries, while the salaries allocated to women working inside Syria hardly pass the 250 USD mark. Due to this, some organizations opt for hiring five or six women inside Syria because their salaries combined would still be less than the salary reserved for one of the men in the higher posts. This is unfair because women are deprived of equal access to leadership positions in all fields.”

-

The Needs of Women in the Civic Space

The respondents agreed that their most urgent needs are safety and protection. Elaborating on this, a media freelancer said:

“The true influence of the organizations working on women’s empowerment lies in changing the lives of women and girls to the best and enabling them to claim their rights, freedoms, and dignity, as well as encouraging them to participate in public life in the political, civic, and developmental areas. However, this influence remains subpar due to the restrictions, pressures, and violations that limit the work of these organizations and prevent them from offering needed practical support.”

These demands were stressed by a second activist, working with one of the region’s CSOs. She said:

“Above all, as workers in the field of women’s empowerment, we need protection. We must protect ourselves first because our organizations fail to protect us. When a problem happens, they blame the issue on us. Protection can be attained by providing us with crisis helplines that connect us with concerned entities should we face any troubles, especially women who do field work.”

In addition to protection, the respondents said that female employees with women’s CSOs and feminist groups also urgently need equal rights, including equal access to administrative leaves and other work-related rights. On this, a woman working with an Idlib empowerment center said:

“Women in numerous organizations are denied access to their right to leave [. . .]. For instance, several women’s organizations support nurses and medical staff. However, they deprive their own staff members of their authorized days off, whether administrative or sick leaves.”

For her part, the executive director of a north-western Syria CSO placed stress on visibility and necessitated that woman working in the field be sufficiently represented internationally. She said:

“Women working in the field of empowerment must be protected by providing them with a safe working environment. This is where the role of civil society starts, as it should raise society’s awareness of why these women must work to guarantee that they engage in their activities in a space that accepts their work at least. Furthermore, financial independence certainly is a crucial factor for them to continue working. Most importantly, women have to gain fair access to representation at international forums, which I believe is the role of the international community and political and civil entities, such as the European Union. [The international community] must ensure an exclusive and fair representation of these women so they can speak about their issues and channel their voices.”

In matching observations, several respondents highlighted the scarcity of women’s organizations and feminist groups in north-western Syria, emphasizing also the insufficiency of the support they offer to empower the women they target, especially given the lack of sustainable funding; deficient coordination and skill exchange between the organizations; and the heightened insecurity in the region. Expanding on this, an Aleppo-based freelance journalist said:

“The number of organizations and associations, particularly those concerned with women’s affairs, currently existing in Syria is insufficient to cover the women’s needs, especially as women and girls aged above 16 years continue to wrestle with several problems and challenges, such as poverty, illiteracy, displacement, violence, discrimination, and lack of access to basic services [. . .]. There is also a need to improve the quality and increase the diversity of the services provided by women’s organizations to accommodate the varied and changing needs of women and girls.”

Another media worker highlighted the importance of building the capacity of women working in the field of empowerment. At the same time, several activists said that working women in north-western Syria are in dire need of health care, prioritizing psychological support, which is “rarely offered” and often deprioritized when organizations carry out need assessments.

-

Recommendations

Based on a thorough analysis of the challenges, gaps, and urgent needs reported by the interviewees as hampering women’s CSOs and feminist groups from optimizing their work and reaching their potential, STJ came up with several recommendations to each of the parties contributing to these organizations’ struggles:

- De facto authorities:

- Create safe spaces for women to work and thrive, and end any measures that hinder programs promoting respect for the rights of women and girls.

- Stop reinforcing legislation that limits women’s freedom and gives immunity to those who commit violations against them, and instead make decisions that guarantee the protection of women from any form of violence or abuse and hold those who refuse to comply accountable.

- Provide women access to job opportunities within the institutions they have established in a manner that complies with required international standards, on the condition that their presence in these institutions is real and not merely titular.

- Abolish restrictions on women’s mobility without a male companion, ensure that female lawyers and legal representatives can access all places necessary to represent female and male clients, and guarantee their freedom of movement.

- Ensure that women and girls have equal access to jobs and learning opportunities, as well as equal rights within the workplace, including equal pay.

- Advocate education in schools and universities on women’s rights and gender equality and inscribe these notions into curricula to encourage early awareness of gender issues and foster a culture that rejects gender-based violence.

- International community and donors:

- Guarantee the sustainability of funding and programs designed to support and empower women, ensure that they are gender-sensitive and meet the needs of working women and beneficiaries while free from any propaganda, and involve women in project planning and implementation.

- Encourage and support CSOs to conduct studies and research that promote a culture of gender equality and refrain from imposing any projects that might be alien to the region or do not meet the real needs of women.

- Support projects aimed at documenting gender-based violations against women and initiatives seeking to empower women to have an active role in Syria’s future political, economic, social, and cultural life.

- Support projects aimed at raising society’s awareness of the need for gender equality, the equitable participation of women in all spheres of life, and the elimination of all forms of discrimination against them.

- Monitor the work of grantee CSOs, particularly those empowering women and raising awareness of their rights, to ensure they are safeguarding women’s rights, especially their female staffers and volunteers, in terms of both task distribution and pay.

- Civil society organizations:

- Study and review Syrian laws, administrative directives, and decisions made by the de facto authorities to identify their shortcomings—especially those that encourage negative discrimination against women and bolster the status of men in society—and propose legal frameworks that establish complete gender equality.

- Intensify projects that enable women to play their required role in public life and raise community awareness of gender equality. Additionally, promote a culture of gender equality, alter the social and cultural patterns of conduct projected on men and women, and eliminate biases, customs, and all practices based on the belief that men are superior to women or on the stereotyped roles of men and women.

- Reach out to and engage in dialogues with religious leaders and institutions and affirm that gender equality does not conflict with religious teachings aimed at justice.

- Ensure that women are genuinely involved in organizational operations, that their participation is effective and influential, especially in strategic decision-making, and that they are not hired only formally to attract funding.

- Document women’s rights violations without discrimination and share information collected with concerned international actors.

[1] Arja, Hadeel. “The Shocking Practice of “Forced Puberty” in Northern Syria’s Camps”, Daraj, 30 May 2023. https://daraj.media/en/108714/

[2] “Women in Syrian Law: Political and Legal Discrimination and its Social Background”, SCM (Last visited: 23 December 2023). https://scm.bz/en/women-in-syrian-law-political-and-legal-discrimination-and-its-social-background/