Background

On 11 January 2011, the United Nations (UN) Security Council issued Resolution 2504, relative to UN aid delivery to Syria. The resolution put another political tool in the hands of the Syrian government (SG), used to tighten its grip over populations across northeastern Syria and local authorities alike.[1] The resolution warrants the SG to establish a monopoly over the delivery of UN aid allocated to the region. Relief is transferred exclusively by the SG and from SG-held areas, in coordination with the UN Damascus Office, and UN agencies’ partners, including humanitarian organizations and associations.

Under the resolution, the SG’s monopoly stretches beyond aid, also covering development and service projects.

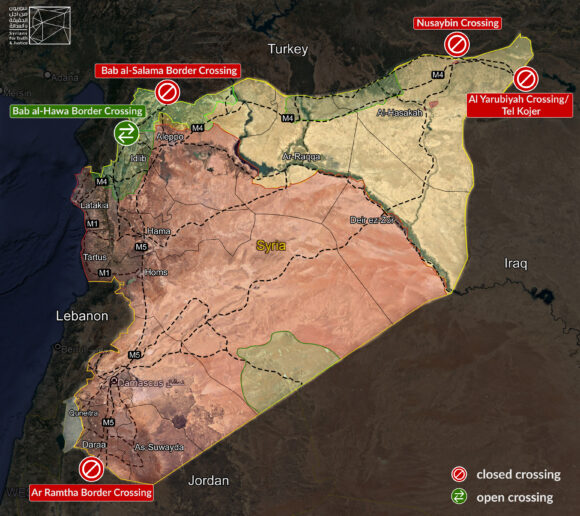

The political weaponization of aid delivery by the SG has been firmly established as the al-Yaroubiya/ Tal Koujar crossing remains shut, and when the Syria-Turkey Bab al-Salameh crossing was blocked following Resolution 2533, adopted by the UN Security Council on 11 July 2020. The resolution authorizes the UN to continue delivering aid to northwestern Syria only through Bab al-Hawa and through cross-lines marking the different territories of control across Syria.

Introduction

In this report, Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) documents the ongoing trends of exploitation and control governing UN aid delivery since January 2020, when al-Yaroubiya/ Tal Koujar border crossing was first blocked.

For the purposes of the report, STJ conducted extensive interviews in 2022 with two groups of aid workers. The first group encompasses three workers from UN agencies: the first supervised aid distribution in northeastern Syria, the second was an employee at an aid warehouse south of Qamishli city, and the third was a field supervisor who monitored local aid distribution teams.

The second group includes employees with local and international organizations operating in northeastern Syria, among them workers with the Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC), and SG-licensed local associations.

In July 2019, STJ published a report documenting how the SARC denied civilians in Daraa and Quneitra provinces access to UN aid. Deprivation of aid was grounded in several pretexts, including that some of the beneficiaries were subject to “security reports”, mostly blacklisting them, or for their former affiliation with armed opposition groups. Both pretexts are used against civilians even though the two target provinces signed “settlement” agreements with the SG in 2018 after SG forces took control with Russian military support.

Notably, the SARC’s exclusionary practices violate the principles of impartiality and independence. These principles stipulate that international organizations remain neutral, do not favor any side in the conflict, and maintain their autonomy of the political objectives of the sides involved in the conflict.

Image (1) – Map marking out the various territories of control, and active and inactive border crossings.

Testimonies Corroborating Aid Misuse

Information obtained by STJ demonstrates that the SG and affiliated security services in the cities of al-Hasakah and Qamishli have been diverting a portion of UN aid to members of the Syrian army, security agencies, the ruling Ba’ath party, and sometimes their families. This diversion is practiced at the expense of rightful beneficiaries, mostly internally displaced persons (IDPs) residing in camps across the two cities and their suburbs.

Two factors warrant such misuse. First, UN agencies’ official or semi-official reliance on SG-linked local partners to distribute relief allocations. Second, the transportation of the allocations through SG-controlled routes, via the Qamishli Airport or land roads.

Even though misuse is confirmed, it remains challenging to fathom the extent of aid appropriation. It is difficult to ascertain the percentage acquired by SG-affiliated Ba’ath Party branches, military, and security agencies because figures on the number of food baskets and medical supplies, especially those meant for combating COVID-19, which arrive in al-Hasakah province monthly, are contested.

However, based on the data collected for the report, STJ estimates that the number of baskets appropriated is likely in the “tens of thousands”.

Notably, the interviewed sources expressed their concern about the SG’s use of relief aid and medical supplies, especially COVID-19 vaccines, as a political weapon, while remedies or alternative delivery mechanisms remain lacking.

The politicization of aid is obvious, particularly when one compares the pace of vaccine delivery across areas of control in Syria. The first batches of the vaccines arrived and were distributed in SG-held areas and opposition-held areas, which access aid through the Bab al-Hawa border crossing. They were received faster in these areas than those held by the Autonomous Administration, whose deliveries are bound by the SG and are transferred through the Qamishli Airport. This comparison does not include the number of undisclosed vaccines which were distributed.

Local Organizations: A Primary Monopoly Tool

Several of the interviewees STJ met said that UN agencies’ reliance on local partners (licensed by the SG) is evidence of the manipulation of aid and attempted politicization of relief.

For aid distribution, the UN and the international organizations it backs depend primarily on the SARC branch in al-Hasakah, Al Birr Association in al-Qamishli, and the Armenian Association, which operates under the supervision of the Relief Subcommittee of the Armenian Church, in addition to a few local associations registered with the SG’s Ministry of Social Affairs and Labor. The SARC finances the logistics of registered local associations, after it divides the province into geographical sectors, and assigns each sector to an association. However, the SARC remains the largest distributor, in terms of the number of beneficiaries and the geographical scope covered.

In addition to recruiting SG-influenced local organizations for aid distribution, a report by the US-based Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), published in February 2022, revealed that UN had contracted with pro-Assad businessmen and local paramilitary groups to implement its projects in SG-held areas. The report cited names such as Mohamad Hamsho and Samer Foz, two businessmen known for their loyalty and close ties with the Syrian president. As for military groups, the report mentioned the Aleppo Defenders militia.

For their part, the Syria Justice and Accountability Center (SJAC) obtained documents showing the role of SG-affiliated intelligence services in directing humanitarian aid and manipulating its flow “to punish perceived enemy populations.”

In a related context, Human Rights Watch (HRW) published a report showing how the SG is “co-opting humanitarian aid and reconstruction assistance, and in places using it to entrench repressive policies.”

Distribution Statistics

An SARC distribution supervisor told STJ that approximately 70,000 families are registered on the SARC’s beneficiary lists in al-Hasakah province. However, he added, only about 85,000 relief baskets arrived in the province as aid allocations in 2021 and 2022. About 44,000 baskets were distributed up to late 2021, and 29,000 baskets were distributed over the first quarter of 2022. The supervisor added:

“A quarter of the reported allocations was not distributed, because security services withhold the larger part of aid in the province’s center. Each operative security service retains a share of aid, whether food or logistics, that are originally meant for affected families at the city center and makeshift housing units.”

Through field monitoring operations, STJ obtained information indicating that security services often repurpose the seized aid. The command of the National Defense militia confiscates over 40% of the allocations’ bulk. They then sell the “shares” on the black market and use the revenues to pay the salaries of volunteer recruits within their ranks.

In addition to military appropriation, STJ detected similar patterns of aid seizures within administrative SG circles. Every month, the SG-affiliated al-Hasakah Provincial Directorate (APD) informs other government departments to coordinate with the SARC, asking the organization to send monthly food baskets to government employees. The APD also maintains contact with the Office of Martyrs and the Ba’ath Party Branch to supply families of dead and wounded recruits of the Syrian army with semi-fixed shares of aid. Amidst this diversion, the APD ensures to fill its own warehouses with baskets. At a monthly rate, nearly 500 aid shares are distributed to security and administrative agencies.

In addition to interviewed sources, STJ collected field testimonies from residents and local relief workers in the area. The accounts revealed the names of other local entities involved in aid misuse. These entities create fake lists, alleging they are of families in need, to access aid. However, no exact figures were reported on the number of names listed, or the size of aid misappropriated.

Notably, at odds with allocations designated and delivered to the province, family beneficiaries have access to merely 25% of the total allocations once every three months, at a rate of 25% in al-Hasakah city and 75% in its suburbs.

According to statistics obtained by STJ, aid is distributed every three months at a rate of 1,255 allocations in Tall Tamr town and its suburbs, 1,600 allocations in al-Hasakah’s countryside, and 3,100 allocations channeled to over 12 neighborhoods within al-Hasakah city.

Additionally, a segment of the designated baskets is reserved for IDPs in al-Hasakah province at a rate of 2,000 allocations, IDPs from Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê at an approximate rate of 850 allocations, and 5,000 allocations in al-Shaddadi area, which encompasses Markadah, al-Arishah, and al-Shaddadi towns.

With this, the total the SARC distributes across the province amounts to 13,805 shares, covering only a fraction of the needs of the organization’s 70,000 registered family beneficiaries.

Restricting Projects to Specific Areas

Employees with Qamishli-based UN agencies told STJ that the agencies are encountering some challenges under the control of the Autonomous Administration, which presides over the larger parts of northeastern Syria, especially with obtaining permits to implement UN-led projects. In addition to permits, it remains difficult for agencies to assess needs in areas outside the SG’s control, which hampers relief efforts in these areas.

However, even when data on the size of need is available, projects continue to be focused in certain areas. During the draught which hit northeastern Syria between 2005 and 2010, most of the SARC’s relief activities, which were carried out in partnership with regional and international organizations, such as the Arab Organization for Agricultural Development and UN organizations, were concentrated in Arab-majority areas in the southern countryside of al-Hasakah and Qamishli, neglecting the Kurdish-majority areas, despite there being reports assessing needs there.

After 2011, UN programs widened the scope of assessment, seeking to meet the needs of struggling families across the entire region. However, some livelihood programs initiated by the UN Development Program are still concentrated in SG-held areas in the southern countryside of Qamishli.

Tools for Manipulating Aid

Several factors play into the SG’s politicization of aid, which it uses to win over populations in certain areas. The SG manages to repurpose aid into a mechanism of political pressure because the UN recognizes the SG as its main courier and coordinator. So long as the al-Yaroubiya/ Tal Koujar crossing with Iraq remains blocked, and the SG continues to predominate land routes.

According to testimonies obtained by STJ, the SG resorts to several practices to control, maintain a monopoly over, and manipulate aid:

- Pressuring UN Damascus offices to back certain merchants with tenders related to in-kind materials.

- Transferring cash to executive partners through official banks based on the official exchange rate, which is lower than the market rate. A dollar’s purchase rate is 3,955 Syrian Pounds (SYP) and the sell rate is 3,990 SYP on the black market, while the official exchange rate, determined by the Central Bank of Syria, was 2,814 pounds per dollar up to 2 April 2022.

- Limiting UN programs to specific associations that have links with relevant ministries, and thus facilitating these associations’ access to official approvals related to the programs.

- Amending laws to enable the SG to support some associations, or bar others, linked to the Ministry of Social Affairs and Labor. For example, church-related associations did not need permits from the ministry to enter into partnerships with the UN. However, the SG later made the permit obligatory and simultaneously denied associations access to it.

- Allowing security branches to exercise absolute authority over UN offices in Qamishli, which are exposed to several provocations, including focusing aid delivery in certain areas and taking bribes from associations that implement projects.

- Obliging UN programs to employ specific persons for security persons or personal gain, in addition to taking bribes and diverting aid.

UN Programs and Their Locations of Operation

UN agencies follow several aid distribution mechanisms, including in-kind deliveries, which constitute over 90% of the total volume of aid, cash programs, or electronic vouchers. A part of the in-kind aid is purchased from Damascus’s markets through tenders. The remaining portion is imported from the agencies’ financing departments located in several European countries, including Italy, Switzerland, and Denmark.

Several UN-linked agencies and organizations operate in the areas held by the Autonomous Administration, providing various types of services:

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) runs programs that mainly support the 900 Iraqi families in northeastern Syria, in addition to providing shelter and protection services in camps, which host both refugees and IDPs.

- The World Food Program (WFP) provides programs that support pregnant and lactating women in al-Hasakah province, granting them cash assistance. Additionally, the WFP provides food baskets to impoverished families, living in and outside camps through partnerships with a number of charities, including the Al-Mawaddah charity association.

- The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) provides water support across al-Hasakah province and supports infrastructure related to the water and sanitation network there through partnerships with relevant departments and ministries. Additionally, UNICEF provides monthly hygiene baskets to families in camps through partnerships with local associations, including the Al Yamamah Charitable Association. It also supports the education sector in SG-held areas and provides child protection services in camps.

- United Nations Development Program (UNDP) implements projects to improve the livelihoods of struggling families in northeastern Syria, especially in SG force-controlled areas in the southern countryside of Qamishli. The UNDP supports the beneficiaries to start their own projects, after offering them the necessary training.

- The World Health Organization (WHO) supports the health sector in SG-held areas and supports and supervises vaccine administration programs in northeastern Syria in cooperation with the Autonomous Administration. It also supplies SG-operated hospitals with necessary medications and medical equipment.

The SG’s Legal Obligations

The SG’s Constitutional Obligations

Providing public services to citizens is the State’s primary responsibility and fundamental to the social contract between the people and the State. These services revolve around human necessities, which preserve life and ensure dignity. Article 13 of the 2012 Syrian Constitution states that the “Economic policy of the state shall aim at meeting the basic needs of individuals and society. . .”. Pretexts such as exceptional, or similarly urgent, circumstances in the country do not exempt the SG from this responsibility because, according to Article 22 of the constitution, “The state shall guarantee every citizen and his family in cases of emergency, sickness, disability, orphan-hood and old age.”

Because the State is constitutionally obliged to provide basic needs to society and individuals, it must avoid the common practices documented in this report, including the manipulation or control of humanitarian aid, and its use as a tool to pressure the local population.

Should the State be unable to provide basic services for any reason, it should not use humanitarian aid provided by UN bodies or other countries discriminately, on any basis, including political loyalty. Additionally, the SG’s diversion of a portion of UN aid, as the report confirms, to members of the Syrian army, security services, the Ba’ath Party, and their families, at the expense of IDPs in camps and families most in need of such assistance, is a violation of the principle of equality, established in Article 33 of the constitution. The article states that “Citizens shall be equal in rights and duties without discrimination among them on grounds of sex, origin, language, religion or creed.”

Furthermore, the SG’s distribution of WHO-supplied COVID vaccines in its areas faster than in others, especially in Autonomous Administration-held areas, contradicts the principle of balanced development across Syria, enshrined by Article 25 of the constitution. The article prescribes that “Education, health and social services shall be the basic pillars for building society, and the state shall work on achieving balanced development among all regions of the Syrian Arab Republic.” The discrepancies in vaccine administration also breach Article 22 (2) of the constitution which provides that “The state shall protect the health of citizens and provide them with the means of prevention, treatment and medication.”

The SG’s Obligations under International Law

Under international law, the State bears the primary responsibility for providing the basic needs of the civilian population within its control. Therefore, “[e]ach State has the responsibility first and foremost to take care of the victims of natural disasters and other emergencies occurring on its territory. Hence, the affected State has the primary role in the initiation, organization, coordination, and implementation of humanitarian assistance within its territory.”[2] Based on this, the responsibility of the international community to provide humanitarian assistance to the population of a State remains a secondary obligation, which enters into effect only when a State fails to meet its primary responsibility.[3]

Although Article 3 common to the four Geneva Conventions, applicable to non-international armed conflict, does not explicitly address the issue of humanitarian assistance, which is this report’s subject matter, it does include a general principle that requires humane treatment of persons who do not take an active part in hostilities without any discrimination. This obliges all parties—and the State, as a primary official entity, ahead of all others—not to expose the civilian population to situations that threaten their dignity through lack of basic supplies, which may also result in psychological or physical suffering.[4]

Therefore, Syrian authorities are obligated to provide relief, allow, and facilitate delivery when unable to provide relief themselves, to the civilian population acting on the principles of humanity and impartiality and on the basis that relief work is carried out without any discrimination. This legal obligation is enforceable in all cases as a reflection of customary international humanitarian law.[5] Accordingly, because Syrian authorities had approved relief work by external actors, they have the duty to ensure the freedom of movement necessary for these actors to carry out their functions.[6] Freedom of movement is hinged on the fact that this aid is humanitarian and impartial, and on the basis that humanitarian actors distribute it without discrimination of any kind.

The Syrian authorities’ manipulation of humanitarian aid, as stated in the report, is a violation of their legal obligations, stemming primarily from adherence to the principle of State sovereignty. This principle is observed through the UN’s obtaining the SG’s approval and coordinating its functions with the SG as an external actor providing impartial humanitarian aid.

The Syrian authorities’ confiscation, establishment of a monopoly over, or dictation of pathways for humanitarian aid distribution does not only amount to manipulation and diversion of aid, in violation of the provisions of international law.[7] It also amounts to circumvention of international law, especially the rule necessitating ensuring the freedom of movement for humanitarian actors.

The Syrian authorities’ practices can be also observed as a deliberate misinterpretation and miss-application of the exceptional circumstance of an urgent military necessity, under which the activities of relief workers can be limited or their movements temporarily restricted.[8] Claims of military necessity should ensure that relief operations do not overlap with military operations in order to protect humanitarian actors, and should not be put forward arbitrarily, especially since roads leading to the areas targeted by these humanitarian operations, as mentioned in the report, or the areas themselves are under the control of the Syrian authorities. Therefore, preventing aid delivery to specific areas under the pretext of military necessity is futile, a groundless legal argument, and an abuse of legal rules, oriented towards exercising unfair discrimination against population groups under the jurisdiction of the Syrian authorities. Denying populations access to aid may amount to subjecting them to collective punishment, which is prohibited under the customary international humanitarian law.[9]

The Syrian authorities’ practices of manipulating, appropriating, and diverting aid, and, accordingly, depriving multiple segments of the civilian population of their right to access humanitarian aid, may amount to inhuman treatment as intended in Article 16 of the Convention against Torture. Lack of food and other supplies essential to the survival of the civilian population can cause severe physical and mental suffering, which constitutes a form of inhuman treatment as indicated by several rulings of the Commission on Human Rights.[10] Moreover, these practices are a blatant violation of the obligations of Syrian authorities towards ensuring the right of individuals and groups within their jurisdiction to food. Therefore, the duty of the State to respect this right obliges it not to take any measures that would block access to food. Additionally, its duty to protect this right obligates it to prevent any party from depriving civilians of this access, and its duty to implement this right obliges it to actively engage in measures and activities that enhance people’s access to their basic needs, especially food. Based on the report’s findings, in addition to the possible violations of international humanitarian law, Syrian authorities, including branches or parties involved in manipulation, acquisition, transfer and deprivation of aid, are considered agents of the State, and therefore it is the State that shall bear responsibility for their wrongful acts.

Recommendations

Because the Damascus-based SG’s power over humanitarian aid and its entry routes sustains corruption and disrupts the UN agencies’ control over their operations, STJ recommends:

- Applying pressure to reactivate aid delivery through al-Yaroubiya border crossing and assigning delivery to trusted and politically neutral local organizations to ensure indiscriminate access to relief for all Syrians.

- Investing in efforts to achieve a convergence of views, resolve disputes between the SG and local authorities, and ensure the independence of the humanitarian issue and relief of political polarization.

- Assigning the administration of development and service projects to independent organizations and associations, subjecting these organizations to UN monitoring, and tightening monitoring mechanisms.

- Reopening the al-Yaroubiya border crossing for UN aid delivery, working with independent organizations, and curtailing the control SG and SG-affiliated organizations enjoy.

- Urging international organizations and bodies that obtained the SG’s authorization to conduct an objective and transparent review of their work dynamics and assess the impact potential SG-led violations might have on their legal responsibility for those violations, in line with the provisions on the Responsibility of International Organizations.

_______

[1] Resolution 2504 extended the authorization of cross-border aid delivery mechanism from Turkey to Syria, only through Bab al-Hawa and Bab al-Salameh for a period of six months, excluding al-Yaroubiya crossing with Iraq and Ramtha with Jordan. While efforts to reactivate aid-delivery through the excluded crossings failed, access through Syria-Turkey crossings was also limited to only Bab al-Hawa in July 2021, blocking Bab al-Salameh.

[2] UN General Assembly Resolution 46/182 (1991, Annex, para. 4; see also UNGA Res. 43/131 (1988); UNGA Res. 45/100 (1990); UNSC Res. 1706 (2006), para. 12; UNSC Res. 1814 (2008), para. 17; UNSC Res. 1894 (2009), preambular para. 5 and 6; UNSC Res. 1906 (2009), para. 3; UNSC Res. 1910 (2010), preambular para. 16; UNSC Res. 1923 (2010), para. 2 and UNSC Res. 1970 (2011), preambular para. 9.

[3] UN Secretary-General, Report on the protection of civilians in armed conflict, UN Doc. S/1999/957 (1999), para. 51, as reiterated a decade later in the Secretary-General’s report on the same topic of 2009, S/2009/277 (2009), para. 7; see also S/2001/331, para. 51 and S/2004/431, para. 24.

[4] ICTY, the Proescutor v. Zejnil Delalic et al., Case No IT-96-21-T, Judgment, 16 November 1998, para. 543: “In sum, the Trial Chamber finds that inhuman treatment is an intentional act or omission, that is an act which, judged objectively, is deliberate and not accidental, which causes serious mental or physical suffering or injury or constitutes a serious attack on human dignity”.

[5] IHL Database, Customary IHL, Rule 55.

[6] IHL Database, Customary IHL, Rule 56.

[7] According to Article 70(3)(C) of Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions, included in Rules 55 and 56 of the customary international humanitarian law.

[8] According to Article 70(3) of Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions, which reflects the customary IHL, under Rule 56.

[9] IHL Database, Customary IHL, Rule 103.

[10] See e.g., Tshisekedi v. Zaire, No. 242/1987, para. 13 b; Mika Miha v. Equatorial Guinea, No. 414/1990, para. 6.4; Mukong v. Cameroon, No. 458/1991, para. 9.4.

1 comment

[…] the Syrian army, security agencies, the ruling Ba’ath party, and sometimes their families,” the report […]