Background

The events which the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou witnessed in March 2004 were a turning point, as they reshaped the relationship between the Syrian Kurds and the Syrian authorities, for the Kurds have unfailingly suffered from marginalization, discrimination and alienation at the hands of the successive governments which held the reins of power in Syria. It was the first time that such large-scale protests be organized by the Kurds; both the intensity and the momentum of which bothered the Syrian authorities that, for their part, answered with excessive repression. Casualties, as most recent records indicate, amounted to no less than 36 dead persons, mostly Kurds, and the injury of more than 160 others, in addition to the security services’ arrest of more than 2,000 Kurds (most of whom were pardoned later on), the torture and the maltreatment of whom was documented by several reports.[1]

On Friday, March 12, 2004, the events in the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou, al-Hasakah province, kicked off, spurred by immediate clashes between the fans of the Deir Ez-Zor-based al-Foutoua team and those cheering for the local team of al-Jihad on a football match during the Syrian League, stones and edged weapons were used. The armed friction necessitated that the Syrian police forces and security services intervene, which shot at the angry fans with live bullets, especially the Kurdish ones, gunning down no less than six persons. The next day, on March 13, 2004, the event swirled into massive and wrathful protests, swiping over many Kurd-populated cities and areas throughout Syria, especially in al-Qamishli/Qamishlou, Amuda, Ad Darbasiyah, Sari Kani/Ras, Kobane/Ayn al-Arab, Afrin and the Kurdish neighborhoods in Aleppo city — Ashrafieh and Sheikh Maqsoud, and the ones in Damascus, including Wadi al-Mashari and the al-Madinah al-Jamiea/the University City, in addition to Terbeh Sbiyeh/al-Qahtaniyah and Dêrik/al-Malikiyah among others. The fight and the protests that ensued were later on called the al- Qamishli Events or the Qamishlou Uprising, during which several people fell dead, dozens were injured and hundreds were arrested.

What aggravated the situation further was some sides to the authorities’ relaxed attitude towards shooting unarmed citizens in other places, followed by the arbitrary arrests of hundreds of Kurdish youths and a months-long siege, the acuteness of which lessened after the first few days from the stadium’s incident, imposed on the neighborhoods and towns incubating a Kurdish majority. Worse yet were the news reporting that Arab villages and tribes, adjacent to the Kurdish villages, were being armed, which were also to be deployed in repressive activities and catalyzing terror.[2]

Contrary to the news, which spread over the first few days, reporting that children were trampled[3] to death following the clashes at the football pitch, the incidents have, later on, been proven as untrue even though protestors where shot at on the match’s day and the days that followed.

Analysis, addressing the long-term reasons for the events, varied; however, many of them, at the time, pointed out that the protests, in one way or another, were tightly linked to the ongoing war in the neighboring country, Iraq, for offsetting Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq in April 2003 has given rise to Deir ez-Zor tribes and the Arab political powers’ feelings of severe indignation concerning the policies of the Kurdish parties in Iraq, which turned into resentment of the Kurds in Syria, the majority of whom are based in the al-Hasakah province, the city of al-Qamishli in particular.[4]

The statistics on the number of casualties and detainees at the time did not match, for the Kurdish sources reported that about 40 Kurds died while the official Syrian sources estimated the number of fatalities with about 25 persons.[5]

Concerning the detainees, the al-Qamishli Events triggered a large-scale arbitrary arrest campaign, which targeted hundreds of Syrian Kurdish youths, children included, who got released in batches after being held in detention for varying periods.[6] On March 30, 2005, the Syrian Arab News Agency/SANA reported the issuance of a Presidential Amnesty Decree involving all the Kurds who have been detained as a result of the al-Qamishli Events in 2004, adding that the number of persons detained amounted to 312 prisoners.[7]

Besides the unfair arrest of dozens of the Kurdish students of Damascus University, many were permanently dismissed from the universities throughout Syria. On March 18, 2004, an “investigative committee,” formed by the University of Damascus, made several decisions, based on Article No. 134 of the Rulebook of the Universities Organization Act, providing for the permanent dismissal of the Kurdish university students —21 male and female students, in addition to the dismissal of several students from the University City in Damascus.[8]

In this report, Syrians for Truth and Justice/STJ seeks to document and describe the merits of the al-Qamishli/Qamishlou Events in 2004 on the one hand and to put a spotlight on the torment of several victims of these events on the other, those who got wounded and others who got detained for various durations by the Syrian security services.

In terms of methodology, this report is based on a total of (13) testimonies and interviews: (6) interviews were conducted in person with eyewitnesses by STJ’s field researchers; the other (7), nonetheless, were conducted with the eyewitnesses online. Concerning the geographical location, the testimonies and interviews, for their part, cover several Syrian areas, where the eyewitnesses are based, starting from the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou, Ad Darbasiyah and Sari Kani/Ras al-Ayn, as far as al-Hasakah. In addition to this, many reports and sources are referenced here, which have all documented the 2004’s events.

First: Al-Qamishli Events in the Eyes of Locals and Witnesses

The al-Qamishli Events, dating back to 2004, took a toll on numerous Syrian Kurds, who fell either dead or wounded, as reported by the eyewitnesses interviewed by STJ. Fifteen years have passed since the events, but many are yet tormented by the repercussions, physically and psychologically.

1. Would Masoud Barzani Give You His Leg, if Yours is Lost?

Khoushyar Ramadan Hussain, born in the city of al-Qahtaniyah/Terbeh Sbiyeh, al-Hasakah province, in 1984, was shot during the protests that broke out in the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou in 2004, leaving him with physical damage that is to accompany him to the rest of his life. Going back in time, he narrated the following to STJ[9]:

“On March 12, 2004, I was home on a break from the military service. I knew that some sort of fight has taken place in al-Qamishli’s stadium. I was thrilled to go there, but my father did not allow it. The next morning, we heard that a massive protest was sweeping the streets, performing a funeral ceremony for the people who died in the city of al-Qamishli during the stadium’s clashes. It took me no time, I headed there and joined the protestors. We were near the city’s granaries. I recall that the buses stopped moving, for the shooting was heard. Some buses started even to withdraw. I got off the bus; the people in my company also got off. We all resumed on foot. We joined the protest, walking beside the protestors. We reached the Customs Building, with the dead people’s processions and approached the Fodder Directorate. I still remember that at every government department, there was armed personnel, and they were shooting. However, we, the protestors and me, were all excited and boiling. We brought down the regime’s photos and flags. We walked with the processions as far as the granaries. There, the personnel started to shoot in the air. I did not see anyone getting hurt near the grain silos. Shortly, however, the protestors found their way into the granaries from the northern side. About half an hour later, we could hear the bullets; they cracked behind us. The youngsters looked back, only to see a military vehicle. It came from behind, entering the Rmelan Garage/governmental entity. They opened fire on the protestors. We, in turn, darted towards the garage. One of the personnel fell to the ground. Upon attacking him, the other soldiers congregated and aimed at us.”

Firing live munition on the protestors rendered many of them wounded. A girl fell to the ground, whom Kkoushyar dragged and placed in one of the houses there. What he never contemplated, back then, was that he will be injured himself. He was rushed to the al-Rahmah/Mercy Hospital in the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou. The hospital was crowded, so he was transferred to the Nafedh Hospital, where the doctors informed him that the bullet hit the sacroiliac joint and entered the abdominal cavity, causing damage to both the colon and the bladder. Commenting on this, Khoushyar said:

“I spent about 20 days at the Nafidh Hospital and another 20 at the National Hospital. Regarding the others, who had less severe injuries, they were being treated at houses. I, however, was hospitalized along with four or five other injured to the al-Rahmah Hospital, which was overcrowded at the time. My condition being somehow risky, they took me to the Nafidh Hospital. I remember that I did not lose conscience in the operation room, for one of my paternal uncles was among the anesthesia team. Two days later, they reported my situation to my division. In the hospital, two guards were deployed at my door. None of the human rights organizations was allowed to enter my room, not a person was allowed in without their permission being a Military Service recruit.”

Khoushyar spent 20 days at the Nafidh Hospital in the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou before he was transferred to the National Hospital. Before taking him to the latter, he was led to one of the security branches even though the doctors told the personnel that he is not fit for such measures. At the branch, he was asked questions that he no more remembers. Then, he was transported to the National Hospital. On this note, he added:

“I spent 20 days at the National Hospital, during which I was interrogated by the Syrian security services. They wanted to know what brought me to this state. I did not tell them the truth and the good thing was that the incident happened on a day different from the day off I took from military service. I told them that I was heading to get a train ticket to go back to my division because the buses were all out of service that day. They accused me of lying, so I said: ‘It is up to you; you can write the report as you wish.’ They did write the report, and, 20 days later, they transferred me to the Deir ez-Zor Military Prison. Back then, I was using a crush, and I could not walk properly, for the bullet had hit the colon, bladder, ureter and the sacroiliac joint. I was held captive for two days in the Deir ez-Zor Military Prison. They, then, took me to Aleppo city, wearing my military uniform, where we stayed for a night. I spent another night at the Balloneh Prison in Homs. Next, they took me to the Military Police Department in the al-Qaboun neighborhood, Damascus city. And again, they retransferred me to the Tishreen Hospital Prison. It was not inside the hospital’s building, for there was a prison, annexed to the hospital, with patients in it. They, then, transferred me to the city of Daraa, from where they took me to the town of As Sanamayn. The constant movement caused further damage to my joint. Another wounded, whose name I won’t disclose, accompanied me. His injury was so severe that his colon and intestines were outside his body. He had to defect in a bag, for the doctors told him that his colon must remain outside for two months to get better, and then be returned inside, into its place.”

With the wounded man, Khoushyar arrived in the Deir ez-Zor Military Prison. The personnel ordered him to take off his clothes, getting ready for beating. His injured companion showed the personnel his intensities hoping that he will not be subjected to punishment, for they have been already beaten throughout the journey from one prison to the other. They also got infected with lice at the Balloneh Prison in Homs. When Khoushyar arrived into his regiment in Daraa province, his health had already deteriorated and kept aggravating in time. The commander of the military regiment did not give him the permission he needed to be transferred to the hospital though he could not eat. The operations he underwent in the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou were also badly affected while he was being moved between the security branches. He said:

“I was yet in the operation room when they ordered transporting me to the National Hospital. And I do remember that when they transferred me to the Deir ez-Zor Military prison, my dad protested and had a fight with them. He asked them to transport me aboard an ambulance to Deir ez-Zor and that two patrols accompany me. He also told them that he shall pay all the costs and the expenditures of the two patrols, covering food, fuel and other purchases. However, they refused. One of them even intended to insult my father. He said to him: ‘We are taking your son from here to the Military Hospital in Deir ez-Zor. From there, we will take him to Aleppo aboard an ambulance.’ Unfortunately, none of these happened, for I was transported onboard military vehicles with prisoners, escapees and those charged with crimes. The other thing that I did not mention about the matter is that I was in a dire need for blood transfer at the National Hospital, so two of my friends came and one of them donated blood. But, alas, on their way out of the hospital, they were arrested by the Syrian security forces and spent about a month in prison. I also recall that when I was injured, two of my maternal aunts saw me falling to the ground. They searched for me at the hospitals, believing that since I was a soldier, I would be transferred to the National Hospital. They, accordingly, headed there. They, however, were denied entry by the militants and were told that there are no wounded at the hospital. The soldiers held up weapons to their faces, telling them: ‘If you won’t leave, we will shoot you.’ They stayed until a doctor came and informed them that the hospital has been emptied and prepared to hospitalize injured soldiers only.”

Having waited for a long time, the commander of the regiment approved transferring Khoushyar to the al-Mazzeh Military Hospital, Damascus city, where the doctors deliberately took long to address his condition, knowing that it was worsening and his left kidney was failing, about to stop. He was, as a result, moved to the Harasta Military Hospital, where a doctor, who Khoushyar described as ‘good,’ examined him and took care of his health. The doctor recorded all the health-related issues that Khoushyar suffered and pointed out to the ill-treatment he was subjected to at the al-Mazzeh Military Hospital. He also reported Khoushyar had a special condition and that he was being tortured while being transferred between the different prisons, adding that he spent ten days moving between the al-Qadam district, where one of his maternal uncles lives, and the al-Mazzeh Military Hospital, for every morning he would show up at the hospital where he will be faced with hundreds of applications and obstacles, only to be refused hospitalization in the end. Khoushyar continued to say the following:

“The commander of the regiment refused to transfer me to the al-Mazzeh Military Hospital until my father and mother came to the division and implored to the Brigadier General. I spent a long time at the Harasta Military Hospital, almost eight months. Then, the Medical Committee demanded that I be demobilized, reporting that I was no more capable of performing military service, as I became almost disabled. Nonetheless, the officer in command of my regiment did not approve my lay off. I also remember that I was being summoned to investigation every 15 or 20 days. I suffered thus for a whole year. The investigations, however, were mostly conducted at a military center near the Jisr al-Raess/President Bridge, Damascus city. This is not to mention the harassment and the vexations I was subjected to by the personnel and the officers in my regiment. Once, I filed a day off request and there were five gathering officers. They said: ‘You soldier, what you get to understand of the state you have reached, would Masoud Barzani or Abdullah Öcalan present you his leg if you lose yours?’ I remember saying: ‘What do Masoud Barzani and Abdullah Öcalan have to do with this?’ They then started insulting me and said: ‘Off you go, or we shall annoy you further.’ The investigations continued until my forced demobilization order was issued. But they did not lay me off immediately, for I was demobilized two months after my comrades were demobilized.”

Khoushyar pointed out that he went through hell during the investigations, especially since his health was poor. He used to relay on one leg and use a crush while the detectives accused him of setting fire to the governmental directorates. He was also repeatedly asked if he was a member of so-and-so parties and who his friends were. About this, he said:

“I was supposed to perform military service for two years and a month, but I was kept for two years and three months until the investigations with me finished. I remember that when I went with my friends to take my demobilization document, I could not find my name among those who were supposed to be demobilized. Back then, I contemplated escape, but my family did not allow me. I was scared that they would keep a hold of me or accuse me of crimes, such as murdering a soldier during the events. My health was not that stable as well. My joint needed an operation, but the doctors insisted that I did not need one as long as I was able to walk single leg.”

Khoushyar is yet suffering the repercussions of the injury, for he cannot walk long distances, and he cannot lift heavy weights. Despite his demobilization, one security branch continued to interrogate him. Commenting on this, he said:

“In 2008, I made my mind and decided to leave Syria because my health was poor and also for security concerns, as I had no hope left that the Kurdish dilemma is to witness any changes in the Syria. A thing that I would like to stress is that the investigations were arduous, not to mention the harassment my family suffered every time they paid me a visit at the National Hospital. I also remember that one of the Arab human rights activists, who came to visit me, had to disguise as a nurse and a doctor to enter the hospital.”

The eyewitness Khoushyar Ramadan Hussain. Photo credit: The witness himself.

2. “There was that young man, whose face was split in half by a bullet”

Abdulsalam Omar, another eyewitness who got injured during the stadium clashes in the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou in 2004, born in the city in 1987. He stressed that he is one of the Syrian Kurds denied the Syrian nationality, owing to the special census of 1962[10], which the Syrian government conducted. He specifically belongs to a class of Kurds that came to be known as the Ajanib[11]. To the day, one of the bullets, the Syrian security personnel shot at him, is stuck in his body. Remembering the clashes’ day, he recounted to STJ[12] the following:

“I was at home when I heard that a fight broke out between the Kurdish fans and those coming from Deir ez-Zor and that the government has backed the attacks the al-Foutoua fans embarked on against the Kurds. I also heard that children died due to the stampede; others, however, were wounded on that day. I saw masses of people streaming to the streets from the al-Antariya area. The families of the dead children darted to the streets, and the neighborhood’s residents joined them, I also joined the congregation. In the neighborhood were signs associated with the Arab Socialist al-Ba’ath Party and photos of the late president Hafez al-Assad. I remember that we broke the signs down and shredded the photos. And then, we headed towards the granaries, where several policemen were positioned. The people stoned them, but the policemen retaliated with fire. We immediately alienated ourselves from the source of the bullets and headed to the Train Station. The masses were outraged. Many young people stormed the station and brought out a military vehicle, which they said belonged to the Station’s director. We rendered the car malfunction. We also turned into pieces the president’s photos, in addition to the flags and signs of the al-Ba’ath Party and the state. There were computers also, we shattered these too. We headed to the nearest police station in the al-Antariya next. We let ourselves in the station and there was no personnel inside. The police uniforms were hanging there, for the policemen have presumably put on civilian clothes and abandoned the station. We sat the station ablaze and went on the main street, from where we headed to the city market.”

In the company of the protestors, Abdulsalam arrived at the Fodder Directorate in the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou and the Rmelan Garage/Governmental Entity. They were taken aback, for there was not a soldier there. The masses, for their part, started shattering the vehicles in the garage and set fire to the Fodder Directorate. The people, then, went back home. Abdulsalam going deeper into the details of that day narrated the following:

“The next day, on March 13, 2004, I woke up to find that Armageddon was breaking out in the city. Most of the people were on the streets; none of them stayed at home but those loyalists to the Syrian government. All headed to streets, towards the market again. I also joined them. On our way, we set fire to the Fodder Directorate and resumed the march to the market. We passed by the Customs Building, and near one of the filling stations there, from one of the side streets, a car appeared, with personnel in military uniform on board. They were armed with Russian rifles. Seeing the car, we started throwing stones at it. It was with live ammunition that they answered. A guy beside me was shot in the face, the bullet split his face into two parts, for a gap was formed in his face. We escaped immediately. A door to one of the houses was open, and the owner asked us to let ourselves in and hide. We entered the house, which owner was an Arab. We were surprised for the house was overcrowded with fugitives, who fled the security forces. The house owner wanted to serve us tea, but my friend said that we had to leave the house for the security personnel have left the area. We went out to see the man shot in the face, lying on the ground, three steps away from us. We rushed to help him and hid him at one of the houses, after which we knew nothing about him.”

Abdulsalam traced his way back towards the Customs Directorate in the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou, where he saw the protestors hiding in the corners while the security personnel fortified inside the building. The protestors stoned the building, which the security personnel answered by shooting, rendering several of them wounded. According to Abdulsalam the Customs Building consisted of three floors and no one dared to approach it, the reason why they limited themselves to stoning the personnel and harmed none of them. He added:

“With other young men, I jumped over the Customs Building’s fence, going further inside it. We tried to open its door with our bodies. We wanted to reach the militants who were shooting the people. While we tried to push the door open relying on our bodies, I was shot in the back. I could not breathe and my eyes almost saw nothing but darkness. The young men dragged me to somewhere at the back of the building, where we could shield ourselves, for the militants could have never managed to shoot us there. I resumed breathing and went out of the Customs Building’s courtyard. I touched my back; it was bleeding. A young woman beside me started yelling that this young man is also wounded, [referring to me]. I told her: ‘No, no! It is just a piece of glass that hurt my hand.’ I could not tell them the truth that I have been injured, for they were scared to take me to one of the government’s hospitals, as the rumors said that the personnel were putting the wounded to death there as well. I went back home and stood before the mirror trying to understand what happened to my back. I noticed that it had bled a lot and my shirt was stuck to it, blocking the streaming blood a little. My family noticed what happened to my back, and my father started questioning me into the matter. I remember telling him: ‘I do not know; it is just a piece of glass that hit me.’ I could not summon the courage needed to tell him that it was a bullet. My poor father, he was forced to believe me, for there was not a place where he could hospitalize me to. My family, then, bandaged the wound. On that day, no one could leave his/her house for a curfew was declared. The patrols and the police were arresting any Kurd they would come across on the streets, whether he has or has not done anything. As for my back, I suspected that it was a bullet in the beginning, but the wound healed a few days later. Convincing myself that it was not a bullet, I forgot about the matter, even when I left Syria to Sweden in 2011.”

In August 2018, Abdulsalm felt an ache in his chest and immediately sought doctors, one of whom told him that his chest was alright, but that there was a piece of metal in his back. The doctor asked him if he had been injured or shot in the back. It was then when Abdulsalm recovered his memories of 2004 and especially those dating back to the short time before his departure to Sweden. He said:

“I asked the doctor if it was necessary to remove the bullet, and he said that getting it out would cause me a lot of pain. I was lucky, he said, for the bullet had back then crushed against my strong bones. Were they weak, the bullet would have had penetrated the bones into my chest, becoming deadly.”

The scar caused by the bullet that Abdulsalam received on the protests that followed the clashes at the stadium in the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou in 2004. Taken in: February 2019. Photo credit: STJ.

3. “The Personnel Fired Intending to Harm Us”

Mohammad Ameen Hamzah is not much better than Abdulsalam, for he also got shot during the Stadium Events in the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou in 2004. Mohammad was born in al-Qamishli/Qamishlou city in 1986, and he is yet suffering the effects of the injury he sustained back then. He, below, recounts to STJ[13] what happened on the day that followed the clashes:

“On March 13, 2004, I took part in the protests which took over the streets, taking a stand against what happened at the al-Qamishli stadium on the previous day. While near the granaries, we saw a vehicle boarded with Hajanah Forces/Border Guard[14]. The personnel got off the vehicle and started to randomly aim at us using a machine gun. I do not recall the exact time, but I think it was around 11:30 a.m. or something like that. They aimed in our direction, meaning to injure us. As for me, I was shot in the back of my head, where the bullet finally rested near my right eye. It is still there. I remember that when I first got injured, I was not sure it was a bullet, for some youngsters were using a slingshot, and I thought it was a stone that hit me since the pain was little. I was not aware and never expected it to be a bullet. Upon touching my head, however, I found blood. My legs started to feel numb, my arms as well. I lost power and could not feel anything after that. A month and 15 days later, I was transferred to the al-Rahma Hospital. I remember that my right arm was locked to the bed, so I would not escape. There were two soldiers as well, one on my left and the other on my right side. They gave me too many medications, due to which my stomach burst up. They interrogated my father, asking him about the reasons for my joining the protests against them. When I woke up from the coma, I was the last to leave the hospital among the rest of the people who got injured on the protests. My health was extremely poor; they subjected me to physical therapy, which lasted for about six months. I am yet suffering from difficulty at movement when it comes to the right part of my body.”

Once out of the hospital, security personnel came to recruit Mohammad Ameen, forcing him to perform military service, despite his bad health status. He failed to get a lay off document, which to get he was excessively tormented. He was ordered to refer to the city of al-Hasakah to obtain the remaining documents, where the employees told him that he had to go to Deir ez-Zor province and then to Damascus city. Mohammad Ameen still remembers how his affairs were being hampered and how it was difficult for him to obtain the demobilization document. He had to suffer all of these things, Mohammad Ameen thinks, because he was one of the people who got wounded during the events of the al-Qamishli/Qamishlou city. He added:

“I was left no future in Syria, for after I was demobilized, I tried to find a job. However, everyone was telling me that my name was marked in red, due to which I would not be capable to work. So, I made my mind and decided to leave for Norway.”

In early 2012, Mohammad Ameen decided to move to Norway, hoping to receive proper treatment there. However, and to his disappointment, the doctors informed him that they cannot address his case and that the bullet is to last in his head. They explained that if they were to remove it, he might risk a total paralysis, and both his legs and arms might get affected.

4. “Four Died, We were Told. I believe the Number Rose to Six”

Hamza Hamaki, another eyewitness born in the city of Çil Axa/Twakal, al-Hasakah province, in 1986. Besides working in the field of media, Hamaki belongs to the stateless Kurds, under the class of Ajanib. He narrated to STJ[15] what he bore witness to during the stadium events in the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou in 2004:

“Upon arriving in the local stadium on March 12, 2004, a problem could be easily noticed and the people were many. The match has had already started or was about to start. There were about 300 persons outside the stadium, and we have all just bought the tickets. Back then, everyone from the area was thrilled to attend the match, as it was a top contest. It was a matter of a few seconds, and we started hearing high-pitched sounds, accompanied by abnormal clang, coming from the stadium. We tried to see what was going on through the congregating people. They told us that clashes have broken out between the spectators inside. The guards immediately responded and distanced us a little. They tried to open the gate to the stadium, but due to the density of the people inside and outside, no exit or entry was available. I remember that dozens of people were injured in the head, for they were being stoned. Later on, a friend of mine told me that the fans of the al-Foutoua team had filled water canteens with black pebbles before coming into the stadium. They used the pebbles to stone the fans of al-Jihad team from afar. Fifteen minutes later, the Law Enforcement troops, wearing black, came in. They first kicked us out. We headed to al-Quwatli Street near the stadium and then returned to the place in front of it. They kicked us away once again. A dispute between us broke out, and we showered them with stones. At the time, people were leaving the stadium. My friend and I parted ways as well. We lost each other during the clashes. The problem kept aggravating until it was time for me to return to work, at a hotel in the city of al-Qamishli. It was dark by then, a little after sunset.”

When he returned to the hotel, where he works, Hamza was informed that his friend was shot and that he was treated at the house of a doctor. The workers at the hotel told Hamza that it is better he does not tell anyone, so the security personnel would not summon him. Hamza mentioned that he failed to see his friend Suleiman for 15 to 20 days until the latter showed up at work one day, but he was incapable of doing the work anymore. Hamza added:

“Suleiman’s underarm was injured. He told me that when the clashes began in front of the stadium’s door, there was a policeman, who stood more than a meter away from him. The policeman aimed his rifle at Suleiman, who held his arm up, allowing the bullet to hit his underarm and then exit his body through the back. The next day, four died, we were told. I believe the number rose to six. On that day, when the dead were to be buried, a large-scale protest was on the street. I joined the protest in the morning, around 11 a.m. when it reached the alleys behind the al-Wihdah Street, near the al-Qamishli Hotel. We headed towards and almost reached the al-Sabe’ Bahrat roundabout. And then, we headed to the Customs Building on the Qadour Baik Neighborhood, on the main street. Soldiers were stationed on the building’s rooftops. A number of youths were trying to storm the building; they actually managed to get in and burn few documents inside the building. I remember that the soldiers were shooting in the air as to scare the people off. In the afternoon, we saw the armored vehicles entering the area from the direction of the city market. The shooting, at the time, became random, and the people dispersed and sought the side-streets. We entered one of the houses that opened their doors to the protestors, only to be shocked that about 50 to 100 persons have already been seeking protection in that house, despite its being small. The upper part of the house was surrounded by a brick wall, from behind it we could see random live bullets hitting it. A number of young people chose to stay on the streets and stood before the armored vehicles, many of whom were being targeted as we came to know later. I saw it with my own eyes, a man was shot. He fell to the ground in front of the door to the house where I was hiding. He fell to the ground, and two young men immediately carried him up and hospitalized him. On the same day, a large-scale protest was held on the al-Antariya Neighborhood. Another protest was organized near the granaries and a third in a different place. Each of these protests comprised about 10 to 15 thousand persons.”

Eyewitness Hamza al-Hamaki. Photo credit: The eyewitness himself.

Second: Massive Losses due to Looting and Pillage

In north-eastern Syria, even the shops that belonged to the Kurds did not survive the looting and pillage at the hands of the Syrian security personnel and a number of Arab young people. Several of the eyewitnesses, whom STJ interviewed, reported that the Syrian security services urged Arab young people to sabotage and rob the shops owned by Syrian Kurds, as to overwhelm them.

1. “I Saw it with My own Eyes; Several Shops of Kurds were Set Ablaze after being Looted”

Jindar Abdulqader, another eyewitness born in the city of al-Hasakah in 1985, told STJ[16] that he was present during the stadium’s events in al-Qanishli/Qamishlou city in 2004. He also pointed out to the looting incidents that targeted several shops the ownership of which belonged to Syrian Kurds. He said:

“On the day of the match between al- Foutouah and al-Jihad football teams, like many other youths from the city of al-Hasakah, I headed to al-Qamishli city to watch the game. We actually arrived late to the stadium. When we reached the place, a clash between the fans of the two teams has had happened and had partially subsided. We were told that three children died due to shoving, and many other people who pushed against each other were injured. The fans of the al-Foutoua team went down to the middle of the pitch, where the Law Enforcement troops were also positioned, just at the center. They asked us to leave the stadium when we reached the seats. We noticed that something strange was taking place; the situation was really bad. It was when the regime’s personnel ordered us out of the stadium. Out there, we saw how many people were injured. I also believe that the whole stadium was being cordoned. The people, then, started stoning the personnel and the fans of the al-Foutoua team, which were inside the stadium. This continued for 15 or 20 minutes. The people, next, sabotaged the stadium’s gate, the one located at the side of the al-Siyahi Neighborhood. We wanted to leave through the stadium’s gate, but the number of the people was massive, and the space at the gate was thus jammed. The Law Enforcement troops arrested me, and held captive other two young men. They led us to the pitch and started to severely beat us with the canes they held. Their commander, then, demanded that we be taken. But where to? To tell the truth, we did not know where we were being led. Lucky me, one of the personnel dragged me by the hand and whispered to my ear: ‘Walk with me and say no word.’ He held to my arm until we reached somewhere near the stadium’s gate, located on the opposite side to the bakery. He said: ‘Run a way, and never approach this place, because if they are to arrest you again, you will be in trouble.’ I left through the door, but returned with several young people. Once again they started stoning the Law Enforcement troops. The situation remained thus until the latter managed to exit the stadium through two doors. It was then when they started attacking us. I saw it with my own eyes, they shot live bullets at the people on the street where the Nour ed-Din Zaza Hall is located, on the opposite side of the stadium’s main gate.”

Jindar continued his account of the incidents, adding:

“When we escaped, they shot at us. They rendered two young men injured. The regime’s personnel attacked us, the reason why no one could return to hospitalize the two injured young men. I saw it with my own eyes how the personnel trampled one of the young men; I was not sure if the bullet has hit him in the head, the belly or the chest. I headed to the Kournaish Neighborhood, where relatives of mine stay. I had a glass of water and then sought the bus station. I went back to the al-Hasakah city.”

The next day, the people of al-Hasakah were dissatisfied with what happened in the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou, especially since many young people and children were rendered injured. This urged the city’s people to protest. A number of young men and women went on the streets in the Masaken al-Salhiyah area and called on other people. The number of the protestors increased, for the shop owners and the pedestrians on the main street also joined them, in addition to women, children and elderly. The protestors, then, headed to the city market through the al-Tair/Bird Roundabout, where several of the Law Enforcement troops took position, forcing the protestors to change their direction, as they sought the market. Jindar continued, adding:

“Arriving at the al-Mufti Bridge, we came by many Law Enforcement troops, in addition to firefighters, who used water to coerce the protestors into withdrawal. However, the people did not back down and, rather, attacked the personnel. Two of the firefighters were held by the protestors, who were beaten and released without severe injuries. The protestors next headed to the City Garage Roundabout and then to the Marshou Roundabout. From there, they headed to the al-Qamishli Street, leading to the al-Raess/President’s Square. On the way, the protestors broke down advertorial signs and smashed car windows. We then reached the place in front of the Farmers Union. There, the building’s guards shot at the protestors, rendering several wounded, three young men and a girl included. The shooting increased, and a young man, whose name I cannot remember, fell dead. The protestors held the wounded and rushed them to the Issam Baghdi Hospital, which refused to receive the injured. Accordingly, the people took the wounded aboard cars to the houses of doctors, as to provide them with treatment. We, however, turned back from the Farmers Union to the Issam Baghdi Hospital, passing through the neighborhoods of the Christian citizens. And then, we headed to the al-Sena’a/Industrial Roundabout, referred to as the al-Tair Roundabout. Finally, we returned to the al-Salhiyah Neighborhood.”

One hour later, the Law Enforcement troops took positions on the main street at the al-Salhiyah Neighborhood and stayed there as to prevent the people from embarking on further protests. They spread, according to Jindar’s account, along the main street in the al-Salhiyah Neighborhood, as far as the al-Sabea Min Naissan/7th of April Bakery. Going further into details, Jindar added:

“Several of the al-Ghazel Neighborhood’s residents, mostly Arabs, joined the Law Enforcement troops and attacked the Kurds. No one was left on the streets, and the people have all closed their shops. These residents robbed many of the Kurdish people’s shops, including a cellphone shop, Faris for cigarettes and many clothes shops. The shop owners’ loss was massive. Some of our neighbors, who had shops on the main street wanted to stand before their shops to protect them from looting. And it was then when the Law Enforcement troops started shooting the people, hitting a young man in the belly. The armed man who opened fire was an Arab and his house was located at the al-Salhiyah Neighborhood. He was famous there, for his mother was a Kurd and his father an Arab. The young man with the injury, however, was hospitalized and the bullet was removed. He got better by time. In the next days, I saw it with my own eyes; the Kurds’ shops were being set ablaze and their contents stolen. Other shops’ windows and locks were broken, several others were closed down. A while later, the Law Enforcement troops and their patrols raided numerous of the people’s houses, arresting several young men, including Abdullah Badrakhan, and others from the al-Salhiyah Neighborhood, whose names I do not recall now. Many of them were held detainees, and some of them spent one to two years in the prison, where they were severely harmed and tortured.”

2. “The Law Enforcement Troops were the Ones Urging Arab Young Men to Rob the Kurds’ Shops”

In his testimony, Hassan Alou, a stateless Syrian Kurdish man, classified as a foreigner, born in the city of Sari Kani/ Ras al-Ayn in 1990, told STJ[17] that he bore witness to numerous incidents of looting and pillage in the city of Sari Kani/Ras al-Ayn in the aftermath of the stadium events in the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou in 2004. He said:

“I was 14 years old when the stadium events took place, and we used to own a clothing shop near the al-Bareed Roundabout. A number of Arab young men sabotaged the Kurds’ shops, including the one we owned, for it was robbed and quarter of its goods was stolen. If it was not for our Arab neighbor, who prevented them, they would have stolen all the goods. Back then, the value of the stolen items amounted to 250 thousand Syrian Pounds. It is important to mention, that the value of goods at other robbed shops was estimated at millions, including two belonging to the Malla Darwish family. The Law Enforcement troops were inciting these Arab young men to sabotage and loot the Kurds’ shops.”

Stressing the previous testimony, Sardar Malla Darwish, born in the city Sari Kani/Ras al-Ayn, confirmed that one of the shops they owned in the city was also subjected to looting and pillage on the days that followed the stadium events in the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou in 2004. He told STJ[18] the following:

“On March 13, 2004, following the funeral ceremony of the people who died during the stadium incidents, the residents of Sari Kani/Ras al-Ayn city broke on a protest, following in the steps of other Kurdish cities. Back then, they smashed down the statue of Hafez al-Assad; they also tore to pieces photos and symbols of al-Ba’ath Party at all the city’s governmental departments. When a number of people wanted to attack places such as the Filling Station and the Agricultural Bank, a group of other young men and I prevented them from doing it. This was followed by a large-scale arrest raid in the city, conducted by the Military, Political and State Security Services. Some people were detained and transferred to the city of al-Qamishli, where they were held for more than a month. Others were transferred to the city of al-Hasakah, while another batch was taken to the Sednaya Military Prison. I remember that once we returned home, around 2:30 p.m., my father received a phone call from a doctor at the al-Salam Hospital, located opposite to my father’s shop on the al-Kanaess/Churches Street, telling him that the Arab residents are on the street and want to loot the shops. An hour later, my father was informed that his shop was emptied of everything and was looted before the eyes of the al-Ba’ath Party’s Division Secretary Ayman Attiyeh, from the al-Edwan tribe, and Abu Wael Houkan, the Head of the State Security Detachment and other officers. At the time and in retaliation to the protests held by the Kurds, a group of Arb youngsters gathered at the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party headquarters, who were immediately armed by the regime under the cover of the State Security Service and the party’s division. The affair was, back then, entrusted to awful persons from the al-Edwan Tribe, such as Majid al-Helo, who, inside the very division of the party, said that the Kurds have pissed on the statue of Hafez al-Assad, and we shall take revenge, as we heard at a later date. These persons were known for their fondness of Saddam Hussein, given that the city of Sari Kani/Ras al-Ayn is a home for various ethnic groups, including Arabs, Kurds, Assyrians, Turkmens and Armenians and is a mixture of diverse components.”

Sardar added that many of those who took part in the looting and pillage in the city of Sari Kani/Ras al-Ayn were identified and belonged to the city’s residents, of whom was Ezz Eddin al-Furati, from the al-Edwan Tribe. As Sardar’s account indicates, the Law Enforcement troops and several young Arabs headed to the al-Kanaess Street, aiming at looting, where they left all the shops possessed by Assyrians and targeted the shop owned by Sardar’s father and the one belonging to the his aunt’s son, Abu Salar. He added:

“They smashed my father’s window shop, designated for selling watches, and they robbed him out of goods, the value of which is estimated at about a million or a million and two thousand Syrian Pounds. Abu Salar’s, however, was a goldsmithery shop. There was a gold cutting machine, which they tried to dismantle, but they failed to do so, as they were prevented by a group of Arab men, belonging to the Arab Harab Tribe. The positive thing is that some Kurds and Assyrians, in the company of the Bishop, went to the Arab al-Ba’ath Party Division to calm the situation, but a group of Arabs there, who could feel the taste of power being armed, refused the attempt at pacification. And then, the Law Enforcement and security personnel came, and the city was cordoned for a while. It was then, when an arrest campaign started. Several days later, my father went to his shop, and did not allow us out, for he heard that the regime was arresting young men. Concerned about us, my father presented as a gift the remaining watches to the personnel of the Military Security Service, as to spare us the arrest. I, myself, was prosecuted by the Military Security, but they turned a blind eye to me. However, the State Security Service kept trying to arrest me, and I sought a hiding place at my paternal uncle’s house for 20 days. It was a constant state of anxiety that we lived through, waiting for the raids at night and sleeping in the daylight. They arrested three of my paternal cousins. In the end, I decided to surrender myself to put an end to anxiety. I actually did. I spent two days in detention, during which I was subjected to beating. I, then, was let out. Once, a well-known personality from the city, whose name I do not prefer to mention, showed up and told my father that what happened to me was the price of his being a pro- Barzani.”

Sardar’s family did not wait long before they filed a lawsuit against the robbers, involved in the looting and pillage of his father’s shop in Sari Kani/Ras al-Ayn. Despite the massive efforts they made, the complaint they lodged was registered as against persons unknown, and later on it was totally closed. Sardar pointed out that a state of tension reigned between the Kurds and the Arabs in the city due to the happenings, adding that some of the robbers used to bring the watches they have stolen to his father’s shop for repair.

Third : “Mass Dismissals at the University of Damascus”

Following the stadium events witnessed by the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou in 2004, several young Syrian Kurds held protests in Damascus, in refusal of the incidents. The spark of protests reached the University of Damascus, owing to which numerous Syrian Kurdish university students were dismissed, either ultimately or temporarily, and many others were detained according to the testimonies obtained by STJ.

1. “12 Students Dismissed Once for All”

Ibrahim Murad, born in the town of Tabky, near the city of Dêrik/al-Malikiyah, told STJ that he was a student at the University of Damascus when the events of the stadium broke out on March 12, 2004. He recounted the following to STJ[19]:

“The news from the city of al-Qamishli had already reached us by then, so we congregated, the Kurdish students at the University of Damascus. We started watching over how the matter would turn out and decided to take a stand and protest in solidarity with the Kurds and the wounded. The protest was held around 10:00 p.m. on March 12, 2004 on the Umayyad Square, Damascus city. It was the first time we held such a protest. Once the protest was dispersed, we returned to the University City for the night. We negotiated with the University’s security and officials as to put an end to the massacre taking place in al-Qamishli. We faced many difficulties, for there was a large number of us, the Kurdish students [I mean]. We ended up forming a committee to represent us. The Committee met the University’s official and that of the University City, in addition to the official in charge of the students’ affairs. Most of the students who met the officials were ultimately dismissed from the university later on. The next day, we continued protesting and the number of arrestees, held captive during the Damascus University’s protests, amounted to about 500 male and female students. They wanted to arrest all the Kurdish students to terminate the protests. The students were released 15 days later. The protests resulted in the ultimate dismissal of 12 students and the temporary dismissal of 9 to 10 male and one female students. Urged by the consequences of the protests at the University of Damascus and the incidents of al-Qamishli, I came to the Iraqi Kurdistan to pursue my education. And I am still living here to the date.”

2. “You Must Confess Being a Terrorist Organization”

Haman Ali is another witness, born in the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou in 1981, who was arrested by the Syrian security personnel for participating in the protests in the city of Damascus that broke out to condemn what was happening in the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou. He recounted to STJ[20] what happened back then:

“In 2004, I was a university student at the Media Faculty/University of Damascus. When the events of the stadium broke out in the city of al-Qamishli, all the communication means between Damascus and al-Qamishli were cut, we had no idea what was going on back then. That year, I have had rented a room at the al-Ikhlass Neighborhood/ al-Mazzeh, opposite to the Faculty of Medicine. One of my friends, Shahin Barazanji, and I used to repeatedly visit the university dorms, for we had many friends there. They decided to hold on a sit in, demanding information on what was going on in the city of al-Qamishli. We sat in silence at the square of the University City, opposite to the dorms, where a statue of Hafez al-Assad was erected. We sat there, more than a 100 male and female students, all silent. The administration of the university and that of the dorm came asking about the reason to the sit in, we answered that we wanted to know what was going on in the city of al-Qamishli and that we were worried about our families and relatives, being ignorant of what was going on. There were many rumors, and we wanted any official side to reassure us. They asked us to disperse the sit in. The next day, we gathered again without in advance planning or arrangement. We sat in the square of the University City, doing this for two or three days. Ba’athist students from Daraa and other areas organized a demonstration and attacked us, raising the “long live Syria; long live Bashar al-Assad” slogan. They intended to cause a problem, so we would respond and clash with them. However, we did not speak and each of us went on his/her separate ways.”

On the fourth day, a group of Kurdish students congregated again outside the University City, as they decided to move towards the building of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers in Damascus city, shouting slogans all the way there. The slogans, Haman said, were not anti-government; rather, their content was about the desire to know the truth. Reaching the Umayyad Square, in the center of Damascus, they were taken aback, for the road was blocked. Students, affiliated with the university administration, told them to trace their way back and that the matter will be resolved. Haman added:

“We informed them that were heading to the Presidency of the Council of Ministers to voice our dissatisfaction and complaints, which is a normal thing to do while the people in al-Qamishli were dying and that we had the right to know the reason. Once again, the students were dispersed. We went back and heard that the people of the Wadi al-Mashari/Zorava, the majority Kurdish neighborhood in the city of Damascus, were holding a protest and have already arrived in the area of al-Rabwah. We rushed there and saw the people standing in front of the al-Rabwah bridge. We intended to join their ranks, to be shocked by the Law Enforcement troops attacking the protestors and the students. They hit them. The students stoned them back. However, the troops charged towards us and arrested a number of students. We escaped to a place behind the area’s restaurants. We survived the arrest but heard that they have arrested 15 students, and may be more. From that day on, the security personnel arrested every Kurdish student they caught at the gate to the University City. On that night, or the one after, I do not recall exactly, we heard that the Law Enforcement troops raided the Wadi al-Mashari Neighborhood, especially since the people there did not stop protesting back then. My aunt’s son was one of the protestors and told me that the security personnel wore civilian clothes. Among the protestors, there were security forces also in civilian clothes, who helped in arresting the protestors and surrendering them to the Law Enforcement troops.”

Later on, Haman knew that the security personnel arrested about a thousand persons during the raids against the Wadi al-Mashari/Zorava, the majority Kurdish neighborhood. He pointed out that the arrests targeted several university students, not to mention that many were dismissed from the university, including his friend Shahin Barazanji, Berivan Issa, Mannar Nassi and Masoud Meshou, who were dismissed based on security reports filed against them. Commenting on this, Haman said:

“We gathered on the al-Salhiyah Street once, near the building of the People’s Council; there were dozens of us. The Security personnel came and dispersed us without violence. However, they did not allow us to continue the sit in. At the same time, the students were making action. Some of them tried to find a movement of the Kurdish students at the University of Damascus, which already existed before the events and aimed at helping the new Kurdish students, as well as organizing them cultural and entertainment-based events. Nonetheless, during the incidents, they tried to further organize themselves. As a result, one of the young men, called Shvan Abdou made a statement, through which he announced the formation of the Kurdish Student Union in Syria. The statement addressed the oppression, the killing and the willful targeting of the civilian Kurds in al-Qamishli and other areas. The statement resulted in commotion, and the security personnel attempted knowing who was behind it. One day, Shvan came to the University City and the situation have been relatively calm, 15 days later. But still, many young people were already arrested, to the extent that even a number of the Kurdish soldiers who approached the City’s front, were also getting arrested. While Shvan attempted to enter the University City, he was arrested by the security personnel. They subjected him to an inspection and found a memory card in his possession. Shvan tried to flee to attract the attention of the Kurdish students and to make them know that he was arrested. A friend of ours, Mohammad Ameen Shukri, saw him. Shvan told the latter to inform his friends of the necessity to take care and be cautious so they would not be arrested.”

Following Shvan’s arrest, Haman was also arrested by the Syrian security personnel, accompanied by a number of his friends on March 27, 2004. The security personnel raided one of his friends’ houses in the area of al-Tabaleh, Damascus city, and led him, along with his friends, including Ramadan Khalil and Hassan Bakou, to the Air Force Intelligence Branch in the al-Mazzeh Neighborhood. On this note, Haman said:

“When they arrested us, they blindfolded, assaulted and beat us all the way. They made much fun of the Kurds and deposited us in solitary detention. I remember that I heard the voice of a woman, who was being extremely insulted, for they were calling her by abusive names. She spent one day only there. She was from the Wadi al-Mashari/Zorava and was, besides the excessive insults, abusively treated. We were held in detention for nine days. A high profile officer, the rank of whom I could not tell, however, supervised our interrogation. Later on, when they posted a photo of him, I came to know that he was Jamil Hassan. Today, he holds a key position at the regime’s intelligence services. Back then, he told us that we must confess being a terrorist organization. We told him that we were nothing like an organization. He said that an explosion took place in al-Qamishli behind the Municipality, and we should admit responsibility for it. We answered him that we knew nothing about the explosion. At a later date, we were informed that a sound bomb was blown up behind the Municipality, in the Jaqjaq River. It seems that the regime was responsible for the deed as to make ado. Then, they came for a second interrogation, but we did not confess a thing.”

During his detention period, Haman was subjected to beating and insults. But to his surprise, he saw that his friend Shvan was being held detainee in the cell next to him, and on his door, denied food and water, was written, while he was ordered to stand up for three successive days. Haman added:

“I communicated with Shvan through signs. He pointed out, also in signs, that he did not say anything against us. So, we were not coerced into saying anything. At the time, we spent three days on foot, deprived of sleep in detention. There was a guard at the end of the corridor, watching us over, so we would not sit down. At dawn, the guard would sleep and the place would grow quiet. I used to lay down. There were only two military blankets, and it was freezing. The next day, we were taken for interrogation. They focused on the protests and the sit in, as well as who was behind them. We said that we were getting out on the streets voluntarily, and nothing was organized. We were interrogated for three days, for they were adopting a psychological method with us. One would beat us; another would attempt to get information and confessions, by being nice. We were, of course, blindfolded and ordered on the knees. I remember that they subjected my friend Ramadan Khalil to a torture method called Doulab and hit him with a cane. They did not cause him a [physical] damage, but they beat him until he lost conscience. They, then, brought him into the room and got us food, after denying us any meal for two days. They seemed afraid that Ramadan might commit suicide or something like that; it was for this reason that they brought us food. Ramadan got ill, because he was really underweight. We also caught fever as it was extremely cold. I remember that some militants would insult us, saying: ‘Do you want to establish a Kurdish state?’ Others would say: ‘You are agents of Zionism and America, and you have raised the U.S. flag in al-Qamishli.’ We certainly could never argue with them while they could do anything they liked with us.”

Nine days later, Haman and his friends were released, after being shown up before Jamil Hassan, who literally told them the following: “Do not think of yourselves as heroes, if we wished we would have made you confess. You must show up here every 15 days.” According to Haman, who never went to the branch again, his friend Ramadan referred to the branch regularly, getting insulted for hours before going back home.

Fourth: Arbitrary Arrests

The al-Qamishli events of 2004 corresponded to a large-scale arrest campaign, which involved Syrian Kurds in various Syrian areas, limited not to young people, for also children, not yet 18, were also held captive, as well as elderly. The arrestees were detained for different durations and some of them were taken to the Sednaya Military Prison, where they bore witness to the worst and most brutal times of their lives, which they said will remain engraved in their memory for ever.

1. “You, Halabja People, Do You Expect Us to Throw Roses at You”

Abdulqader Mohammad Ali is born in the city of Sari Kani/Ras al-Ayn in 1955, a stateless Kurd classified as a foreigner. Since 1992, Ali has been working as an international referee, acknowledged by the FIFA, but still he was held a detainee at the Syrian security services’ detention facilities against the backdrop of the events of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou in 2004. There, he was subjected to all kinds of torture. Speaking to STJ[21], he narrated the following:

“On March 12, 2004, I was assigned the referee of a match between the Tishreen and al-Hurriya teams in the city of Latakia. Back then, I was a field judge. The referee, monitoring the game, told me that the match in the al-Qamishli did not go very well, and many incidents have taken place there. I continued the match. Once it finished, I contacted my family because my son Azad, 13 years old, wanted to attend the match at the al-Qamishil stadium, but I did not allow him. As he insisted, I let him go. When I contacted my family, they told me that Azad did not call. I, then, communicated with some acquaintances in the city of al-Qamishli; they also said that they did not see Azad, adding that the area was a hell of anger and no one has any news about Azad. I rented a car and headed home, to Sari Kani/Ras al-Ayn. It was almost at dawn when I arrived in the area. I could not find my son anywhere there. Around 7 a.m. I decided to go to the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou, a security forces patrol stopped me. The officer in command of the patrol, who knew me very well, was a lieutenant called Nawras. We were familiar with each other, so he tried to prevent me from going to the city of al-Qamishli. He said that 12 patrols were spreading along the road to Ad Darbasiyah and another 25 were posted along the road to al-Qamishli. I went back home, but did not have enough patience. I kept calling my acquaintances in the city of al-Qamishli to get the latest news. It was a matter of seconds, when a number of young people started gathering around me. I told them that we at least have to do something to ease the burden of the al-Qamishli. We closed a number of shops belonging to Kurds in the city, and before reaching the city market, our number grew to over two thousand persons.”

The people started protesting at the city center, some of whom attempted to smash down a sign of an Arab doctor; others, however, prevented them from doing it, but it was of no use. He was also informed that another group of the protesting people had set to fire the al-Shabibah/Youth Library, a committee affiliated with the Arab Ba’ath Party. He was informed that Azad, his son, was one of them. On this, he proceeded to say:

“Meanwhile, we headed to the Sari Kani/Ras al-Ayn City Police Station. We found no one inside the station, and we could have stormed it and taken the weapons. But we did not opt for that. We attacked the security personnel detachment. The protestors wanted to storm the house of the area’s manager, but I prohibited them from doing it. Then, we sought the road leading to the city of al-Hasakah. There, a statue of Hafez al-Assad was erected. We sabotaged the statue. In the evening, the protest was dispersed, and everyone went back home. We, however, placed guards everywhere, just in case. The next day, in the morning, a Mardali[22] family called me, saying that the Kurdish shops were being robbed. I inquired into the matter, saying how come? They told me that they have started looting the shops and have targeted my brother’s. He owned a goldsmithery shop on the al-Kanaess/Churches Street. I told them that I was coming. They advised me to take the side streets to reach the place. I actually did. I went to the al-Kanaess Street and reached one of the houses, where the Qadi Aishi family lived. The house was close to my brother’s shop. The owners of the house tried to force me inside their place, fearing that I might be harmed in any way. I saw those who were attempting to rob my brother’s shop. When I approached them, I was taken aback, for the head of the State Security Detachment and the Secretary of the Division where in the middle of the crossing that led to the al-Kanaess Street. A person from the al-Helo family was applying TNT to the locks of the shops and smashing them down. The latter person was a civilian citizen, he was from the very city of Sari Kani/Ras al-Ayn, from the al-Edwan Tribe in particular. I reached my brother’s shop, and someone was trying to break down the gold cutting machine. I beat him really hard. I took a cane from one of the people there and started hitting him. I even spit on the head of the State Security Detachment and the Secretary of the Division, but no one dared to come near me. I heard someone saying: “You, Halabja people, do you expect us to throw roses at you,” indicating that the Kurds deserve being killed. I also beat him hard, broke his arm and headed back home.”

It was not that long, when Abdulqader was informed that his father’s shop in the city of Sari Kani/Ras al-Ayn city, where they sold textile, has also been set ablaze, in addition to the many shops that were looted and subjected to pillage. Arriving at his house, Abdulqader noticed that many people were cordoning his house. He tried to fight them, but he fell to the ground. He was then taken to the State Security Service, where he stayed for three days. There, he was subjected to harsh beating and was then transferred to the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou. Commenting on this, he said:

“When they transferred me to the city of al-Qamishli, both my hands and legs were tied. I was also blindfolded. I saw no one for three months, for they placed me at solitary detention. I was tortured three times a day. They would insult me every time, saying obscene things about Mala Mustafa Barzani, then my mother, sister and wife. I suffered thus for six months. They blindfolded me for the whole duration. They removed the cover on my eyes only once. It was when they brought my son Azad, 13 years old, and tortured him right before my eyes. They, then, transferred him to the province of Deir ez-Zor.”

About the detention in the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou, Abdulqader added the following:

“They fed me bread while my hands were cuffed. They would say: ‘Hurry up, for the wife of your leader is waiting for me’ or ‘your wife is waiting for me’. During my detention, they brought children from the city of Sari Kani/Ras al-Ayn several times. They were about ten years old. They forced the children to confess that I was training them in the Mount Abdulaziz area on conducting explosions and similar acts. The children themselves confessed to me when I was let out. I forgave them, because I knew that they were coerced into saying this. I also remember how they used to hang me by the legs. They shocked my right ear with electricity. They used profane language with me and wondered from where I was driving all the force I had while I repeated how coward I was to myself. I also believe that it was acid what they forced me to drink, causing me a heart attack. They once thought that I was dead, so they took me to the city of Sari Kani/Ras al-Ayn and abandoned me on the street where my house was located. I then started receiving a treatment.”

It was not Abdulqader alone who was detained by the Syrian security services, for both his sons, Azad, 13 years old, and Walat, 15 years old, were also held captive in the city of Sari Kani/Ras al-Ayn for participating in setting fire to the al-Shabibah Committee. According to Abdulqader, Azad was detained for three months by the Air Force Branch. He was imprisoned until the director of the branch asked his troops to bring Azad before him and allowed the child to call his mother, asking her to come and take him. Abdulqader continued his account, saying:

“I was detained for six months. My son Walat, however, was imprisoned for two months. When he was released, his mother was coerced into hiding him somewhere in a village for months. Though I was released, the memory of one of the persons detained with me, called Farhad, is yet stuck to my mind, for the man died one week after he was subjected to torture.”

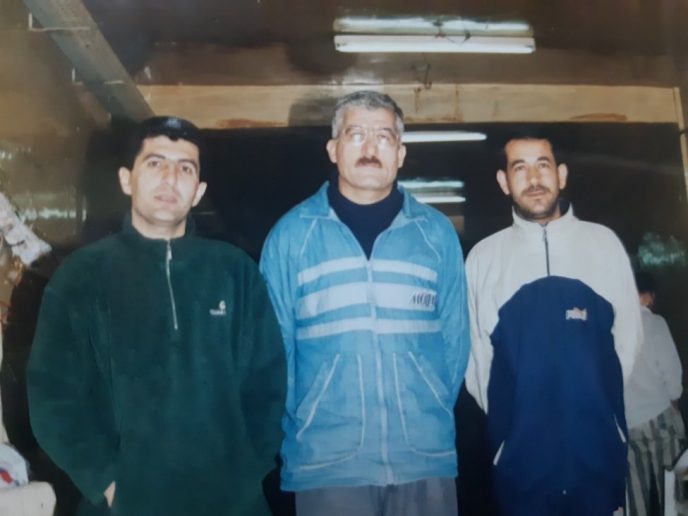

Eyewitness Abdulqader Mohammad Ali to the right of the photo. Credit: The eyewitness himself.

2. “One of the Detainees Died due to Torture”

Mahmoud Jamil Abdulhalim, born in the city of Ad Darbasiyah, al-Hasakah province, in 1961, was also detained by the Syrian Security Services for taking a part in the anti-government protests on March 12, 2004. He was arrested on April 8, 2004 by the State Security in the city of Sari Kani/Ras al-Ayn, from where he was transferred to the State Security Detachment in the city of al-Hasakah and then to the city’s central prison. He was next moved to the Sednaya Military Prison in Damascus where he spent 72 days before he was transported again to the Adra Central Prison, which is also located in the capital, to be released on April 1, 2005.

Abdulhalim believes that his detention was extremely unfair, as it filled his wife and children with fear. About this, he narrated the following to STJ[23]:

“On April 8, 2004, at 2:45 a.m. gunmen affiliated with the State Security Service and the Law Enforcement raided my house in the city of Sari Kani/Ras al-Ayn, after they surrounded all the exits of the street where I lived. I saw seven persons at least inside my house, two of them were face covered. They cuffed my hands, blindfolded me and deposited my in their car, which was parked outside. They hit me in the car. We reached the State Security Branch in the city in 15 minutes, which back then was headed by Basil Koujan, dubbed Abu Alaa. I was beaten until morning. I was severely hit, all over my body. I was insulted and flouted. They also interrogated me and accused me of inciting young people to hold anti-Syrian government protests and commit acts of sabotage, in addition to insulting the Syrian president Bashar al-Assad.”

A few hours into his detention, and putting him to an initial investigation, the forces of the State Security in the city of Sari Kani/Ras al-Ayn transferred Mahmoud Jamil Abdulhalim to the State Security Detachment in the city of al-Hasakah, where he bore witness to horrifying things. He said:

“On the morning of April 8, 2004, I was transferred to the State Security Detachment in al-Hasakah; I was taken there in the company of other detainees while blindfolded. Once we arrived, they forced us to take our clothes off and started beating us all over our bodies. I stayed there for a single day, being tortured every 45 minutes. Of the torture methods I was subjected to was the Ironing Board way. You get vertically tied down on a piece of wood that looks like an ironing board while lying on your stomach. They then start beating you everywhere. On the same day, the Detachment informed the family of detainee Farhad Sabri, 29 years old from the city of al-Qamishli/Qamishlou, of his death. He lost his life due to torture two days before, which the detained doctor Doursen Oskan, who examined the deceased’s body, confirmed. In addition to this, I could hear the shrikes of Kurdish women all the time on that day, being brutally tortured in the prison’s neighboring cells, among whom was a young woman, in her thirties, called Sherin from Dêrik/al-Malikiyah.”

The next day, on April 9, 2004, Abdulhalim was transferred to the Central Prison in the city of al-Hasakah, where he spent five days and was subjected to investigation twice by the National State Security Committee in Syria. At the time, the committee included Hisham Bikhtiyar, Ali Mamlouk and other officers of the Syrian intelligence. On April 13, 2004, with dozens of other detainees, he was transferred to the Sednaya Military Prison, Damascus, where he stayed for 76 days. There, he went through the harshest of days. About this, he narrated to STJ the following:

“We were transported aboard Zeal military vehicles, each containing about 35 detainees. They blindfolded us and cuffed our hands back. The journey continued for 14 hours, the reason why most of us thought that we would be assassinated in the end. It was thus until we reached the gate of the Sednaya Military Prison. They dropped us off and led us. They beat us every step. On both sides of the entrance, there were jailors using different tools to beat us. On each floor, there were different methods of beating. On the first floor, we received bunches. On the second, however, I was hit on the soles of my feet, a method called Falakah; they also slapped me hard on both sides of my head which pierced my eardrum. On the third floor, I was scourged after they placed me in a tire of a tractor. I was tortured for seven hours in a row, before I was taken to the detainees’ rooms called mahja’a/ prison cell. The room where I was deposited was called the retribution cell; it was on the third floor. The room was eight meters long and eight meters wide, and totally lightless. Each room contained 35 to 40 detainees.”

The photo shows an identification document specific for the military prisons. On May 8, 2004, the witness Mahmoud Jamil Abdulahlim was issued a certificate in the Sednaya Military Prison. Photo credit: The witness Mahmoud Jamil Abdulhalim.

In the Sednaya Military Prison, Abdulahlim said, neither the rights nor the dignity of humans is shown regard, and the sole goal of having such a prison was triggering fear in the hearts of the detainees and devastating them spiritually and psychologically, for those in charge resorted to different means of torture, which he enlisted below:

“We were tortured three times a day, after breakfast, after launch and after the dinner meal. Each time, they would choose five persons from each dorm. I, for example, would be tortured once at least every day, not to mention the group punishment, where we would stand next to the wall, facing it. Then, we would be hit by a scourge, while being showered by insults, targeting our families and the Kurdish symbols. The prison’s blankets were infested with lice. The food was bad and inadequate. Every morning, we would get a loaf of bread, three olives and a spoon of yogurt. At noon, nevertheless, we would have bulgur or pasta. The food was always full of pieces of stone that broke the teeth of no less than three people at each dorm. They allowed us to bathe for the first time, 18 days after we were brought into the Sednaya Military Prison. We were forced to get nude and stand for half an hour, screaming and pleading of cold, tortured until it was our turn to bathe, which usually takes us less than ten minutes. After it, they would gather us, while still nude, in the corridor for another half an hour, where they would open all the windows up. Many detainees would get the flue or diarrhea. We, then, would be subjected to group torture until we reached the dorms. We would be tortured individually inside the dorm at times; on others, we would be tortured in a room designated for that end. They continued torturing us until the Qatari Aljazeera channel broadcasted an interview with the President Bashar al-Assad on May 1, 2004, on which he said that they have proven that no external power had played a role in the events and that the Kurds are part of the Syrian national fabric. After the interview, they stopped torturing and insulting us.”

The witness added that following the interview a large-scale voluntary initiative, which Arab and Kurd lawyers embarked on, was launched in defense of all the Kurdish detainees after they visited the detainees at the prisons and were given powers of attorney.

After 76 days of detention at the Sednaya Military Prison, Mahmoud Abdulhalim and dozens of detainees were transferred to the Adra Central Prison, located in the capital Damascus too. There, he was held captive for other 278 days. He summarized his life there, saying:

“On June 27, 2004, we were transported to the Adra Central Prison. There were about 237 detainees. We were all deposited at the Drugs Ward, which contains drug dealers and abusers. We were forced to share the same cells with them. On July 17, 2004, over 100 detainees, nine children included, were released, for a presidential Amnesty Decree was issued on the anniversary of President Bashar al-Assad’s inauguration. However, about 130 detainees and I were not included in the pardon. We were stuck in the same ward till mid-September 2004, for a dispute rose between us and the other prisoners, who were accused of drug dealing and abuse. We held a group protest for hours, demanding that we be moved to another ward. They actually did it, we were taken to a different ward.”

A photo of the witness Mahmoud Jamil Abdulhalim in the middle, accompanied by other two detainees at the Adra Central Prison in the Syrian capital Damascus. Taken on: December 20, 2004. Photo credit: The witness Mahmoud Jamil Abdulhalim.