The “Kayseri incidents” coincided with a series of deportations and racist attacks targeted Syrian refugees and their properties in several Turkish provinces, including Antalya, Adana, Gaziantep, Istanbul, Kilis, Konya, and Reyhanli. In response, Syrians in northern regions, which are almost fully under effective Turkish control, staged widespread demonstrations and protests denouncing the attacks and violence against Syrian refugees in Türkiye.

To recall, on 30 June 2024, Türkiye’s Kayseri experienced protests that escalated into widespread attacks on Syrian property following a rumor about a Syrian refugee harassing a Turkish girl. However, the governor of Kayseri denied this, stating that the refugee had actually assaulted a Syrian girl, not a Turkish girl, in the “Danışmentgazi” neighborhood and the perpetrator was arrested and the girl was placed under protection. The governor urged citizens to remain calm.

Despite the governor’s call for calm, the wave of violence did not stop but rather escalated. This included burning Syrians’ homes, smashing their cars, attacking their shops, and destroying their contents by hundreds of Turkish citizens. On 2 July 2024, Turkish Interior Minister Ali Yerlikaya announced via his account on the X platform that 474 people had been arrested in connection with the riots in Kayseri province. He explained that 285 of the detainees were accused of committing various previous crimes, including migrant and drug smuggling, looting, theft, and damaging property, and that they had previous criminal records. The minister urged Turkish citizens not to be drawn into what he called “provocations,” adding that “those who plot these conspiracies against our state and nation will get what they deserve.”

On 1 July 2024, northern and northwestern Syria experienced increased tensions following protests against the 30 June racist attacks and violence targeting Syrian refugees in Türkiye’s Kayseri.

The protests turned violent as demonstrators began destroying Turkish trucks in eastern rural Aleppo, leading to clashes with the Turkish army in the city of Afrin, northwest of Aleppo. The clashes resulted in at least four deaths and more than 20 civilians being wounded, according to a statement released on 2 July 2024 by the military police of the Syrian Interim Government (SIG), loyal to Türkiye.

The situation prompted the Turkish military, Turkish intelligence, and the Syrian National Army (SNA), which is under Turkish control, to mobilize. Turkish authorities shut down all border crossings with northwestern Syria. On 1 July 2024, the Bab al-Hawa border crossing in northern Idlib announced the suspension of passenger, patient, and truck movements on its official website. The al-Hamam crossing in north Aleppo and the Jarabulus and al-Rai crossings in eastern Aleppo were also closed, but they resumed operations on 3 July 2024. The closure also affected the Bab al-Salama border crossing, experiencing a partial halt in activities before being completely closed on 4 July 2024, according to an official at the Bab al-Salama named Abu Wael (a pseudonym), [1] who explained,

“On 4 July, the border crossing was closed entirely at the decision of the Turkish authorities. The closure lasted six days, including a partial closure, before it was reopened for commercial traffic, individuals holding work permits, and Turkish citizens”.

On 5 July 2024, Green Party MP Ömer Gergerlioğlu criticized the Turkish government’s policy and response to the Kayseri incidents. He stated, “70,000 Syrians were affected, and 21 shops were destroyed by racists,” while addressing the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) during a live parliamentary session in Türkiye.

On 17 July 2024, a group of the Felicity and Future Alliance submitted a request to open a parliamentary investigation into the recent incidents targeting Syrian refugees. The aim was to identify the causes, prevent similar incidents, and implement necessary measures. However, the proposal to open an investigation was rejected by the AKP and its ruling partner, the ultranationalist Nationalist Movement Party.

On 18 July 2024, Syrian civil society organizations issued a statement expressing their deep concerns regarding the notable rise in anti-Syrian refugee feelings in Türkiye, which has led to violent acts against them. They called on the European Union to cease its financial support to Türkiye for Syrian refugees and to promptly take steps to protect their rights.

In the same vein, this report provides details about the forced deportations of Syrian refugees in Türkiye. It highlights how many of them were compelled to sign “voluntary return” papers and were subjected to various human rights violations in deportation centers, including violence and neglect. These actions have occurred in the context of worsening humanitarian and legal conditions for Syrians in Türkiye due to numerous restrictions placed on their freedom of movement.

This report is based on six detailed, first-hand testimonies collected online by researchers of Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ). The testimonies were gathered using a secure communication application. They include accounts from five Syrian refugees who were deported by Turkish authorities to northern Syria before and after the Kayseri incidents.

The sources were informed that the interviews were voluntary and were told how the information they provided would be used, including in this report. All sources chose to conceal their identities or any information that might lead to them for fear of reprisals by the military factions controlling the area. This fear was heightened due to documented previous arrests of deportees upon their arrival in Syrian territory.

The report used testimonies and various open sources such as verified social media posts, deportation figures from official websites, and reports on the violence in Kayseri, the subsequent protests, and related deportations. Some of the information was included after verification.

Escalating Violations Against Syrian Refugees in Türkiye

The events in Kayseri came after a series of deportations of Syrians in the Turkish city of Gaziantep, which is the second largest city in Türkiye in terms of the number of Syrians under temporary protection. According to the Turkish Immigration Administration, Gaziantep is home to over 429,000 Syrians. Recently, there has been an increase in forced deportations of Syrian refugees in Türkiye. Even those with legal documents are being deported for trivial reasons, which goes against the Temporary Protection Regulation issued in April 2014.

Regarding the deportations to Syria during the Kayseri incidents, Abu Wael testified to STJ,

“No Syrians were deported from the Bab al-Salama crossing during the closure period following the Kayseri incidents. Deportations were redirected to the al-Rai crossing, where about 180 people were deported. In April 2024, deportations from the Jarabulus crossing increased to more than 2,000 people.”

The official added:

“Between the beginning of July and 8 July 2024, approximately 160 young men were deported from Gaziantep as part of the latest campaign. Most of them hold temporary protection cards (kimliks) issued by the Gaziantep Governorate, while some were deported for violating terms of residence due to the housing crisis and high rents. Among the deportees, fewer than 20 young men without temporary protection cards aimed to reach Europe.”

The Turkish government plans to distribute the deportees to various crossings and areas, such as Tell Abyad, Jarabulus, Bab al-Salama, and Bab al-Hawa, to relocate them to what it considers “safe areas.” However, according to the administrative official, the challenging living conditions in those areas are worsening the deportees’ suffering.

The Turkish authorities have decided to restrict the publication of statistics on forced deportation at border crossings controlled by the SIG. They only allow data on “voluntary returns” to be made public. This decision came after Syrian opposition websites reported on the number of people being forcibly deported, which the Turkish authorities did not approve of. Additionally, unlike other media reports, filming inside the designated crossings for forced deportations, including in the garages, is prohibited unless special permits are granted.

In February 2024, Turkish Interior Minister Ali Yerlikaya stated that approximately 625,000 Syrians have returned to Syria voluntarily due to improved living conditions in the cities of Jarabulus, al-Bab, and A’zaz, which are claimed to be within a “safe zone.” However, a recent report by Human Rights Watch (HRW) documented that these areas, including the city of Tell Abyad, where Syrian refugees are being relocated, are still not safe. “Türkiye’s ‘voluntary’ returns are often coerced returns to ‘safe zones’ that are pits of danger and despair,” said Adam Coogle, deputy Middle East and North Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “Türkiye’s pledge to create ‘safe zones’ rings hollow as Syrians find themselves forced to embark on perilous journeys to escape the inhumane conditions in Tell Abyad.”

On 18 July 2024, the Bab al-Salama border crossing posted on its official Facebook page that the total number of “returnees” to Syrian territory had reached 3,035 people.

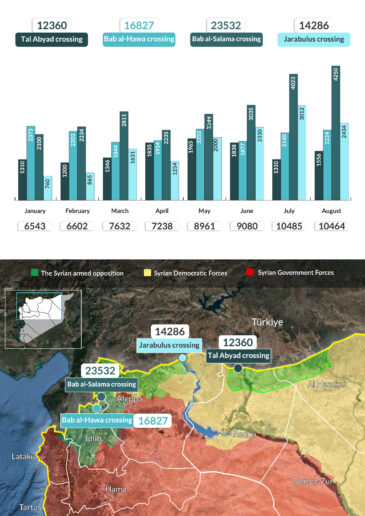

The chart below demonstrates the number of Syrian refugees deported over the first half of 2024, aggregated by border crossing:

Syrian Refugees Face Danger When Walking the Streets of Türkiye

Syrian refugees in Türkiye are facing difficult challenges. They are afraid to leave their homes and often get arrested and detained on the streets and at work. Many of them are forced to go back to Syria even though they have valid legal documents. Unfortunately, refugees in Türkiye lack legal protection.

Asaad al-Hassan (a pseudonym) has been living in Gaziantep since 2017 and holds a temporary protection card (Kimlik).[1] He shared with us his story of being deported against his will and the terrible conditions he experienced on 1 July 2024 saying,

“On my way home after a long day at work, I was stopped by a car from the Turkish Immigration Department near Iran Bazaar Street. The officers asked to see my identification papers and, after confirming that I was Syrian, instructed me to join around 30 other individuals who had been handcuffed with plastic restraints. Despite explaining that my papers were legal and my living status also, they disregarded my words and placed handcuffs on me. After about an hour, the number of detainees grew to about 50 people, and we were transported by a large riot police bus to a police station near the Şahinbey municipality. There, they collected our belongings and personal information before transferring us to the Martyr Kamil Hospital, where we were compelled to sign a medical report stating that we had not been subjected to torture or physical abuse. Subsequently, we were taken back to the police station and spent the night in a communal cell.”

Asaad added,

“On 2 July 2024, we retrieved our belongings and were taken to the Oğuzeli camp for Syrian deportees where we were placed in uninhabitable caravans and cement rooms. I was then coerced to sign a voluntary return document. When I refused, a member of the Turkish security forces beat me with a stick and forced me to sign amid threats and insults. The following day, on 3 July 2024, two officers – I could not identify their ranks – arrived with five large tourist buses, and we were transported to the Bab al-Salama border crossing.”

Mohammed al-Ahmad (a pseudonym),[2] a Syrian refugee in Türkiye who worked in a civil society organization in Gaziantep for six years, recounted that on 27 June 2024, while walking near the Sanko Park Mall with a friend, he was stopped by a car belonging to the Turkish Immigration Department and was forcibly deported to Syria. Mohammed shared his experience with STJ,

“A police officer asked me to show my temporary protection card (Kimlik) and told me to go to the immigration vehicle to check my personal papers. After checking the data, the officer informed me that I was wanted for deportation due to previously fingerprinting voluntary return to Syria papers. One of the officers asked to handcuff me and detain me. I objected to the order and told them that I was not a criminal and would not escape, so he left me in the vehicle without handcuffs. Then they transferred me to the Martyr Kamel Hospital to obtain a medical report confirming that I had not been subjected to torture.”

Mohammed added,

“I was taken to the Beykent police station where I was detained along with four other Syrian workers who were arrested from their workplace in the Gaziantep industrial zone. After five hours, we were forced to board a bus for the Ministry of Interior’s riot police. We were then taken to the Yeşilvadi police station where I found about 25 women with five children, all Syrians. A group was then taken to the Nizip area, and we were taken to the Beyli camp in Kilis where we were verbally abused by private security company employees. We were forcibly fingerprinted for voluntary return to Syria.”

He added,

“On 29 June 2024, at 7:00 a.m., we were taken to the Bab al-Salama border crossing. While there, they discovered an error in my personal information but ignored it. We were kept under the sun for an hour before being allowed to enter Syrian territory.”

In June, approximately 250 young men from Gaziantep were deported through the Bab al-Salama border crossing because they had violated Turkish laws. Their violations included changing their address without proper documentation and not obtaining a travel permit. Meanwhile, the Turkish Immigration Department has been refusing to issue work permits to young men from neighboring provinces like Kilis and Şanlıurfa, where there are insufficient employment opportunities, as stated by Abu Wael.

Deportation at Gunpoint

Malik Abdul Latif (a pseudonym),[3] a tailor who has been living in the Turkish city of Gaziantep since 2015, holds a temporary protection card (Kimlik) confirmed to STJ that his data is up-to-date and that he does not need to update it at the Turkish Immigration Department.

At 12:30 a.m. on 30 June 2024, he was startled by a sudden knock on his door. Upon opening it, he found two Turkish police officers who asked for his name and inquired about the occupants of the house. When he questioned the reason for their visit at such a late hour, they explained that they needed to verify the address of the house. He provided his and his family’s names and was then asked to show his temporary protection card. When he requested to see their identification due to concerns about potential fraud, they became agitated, started shouting and cursing at him, and eventually demanded that he accompany them while threatening him with a weapon. Malik shared the incident with STJ saying,

“I was taken by the police to the station in my home clothes without being given time to change or put on shoes. They filed a report against me for assaulting police officers, which was shocking. I requested to contact a lawyer, but they refused and confiscated my mobile phone. The next day, on 1 July 2024, my fingerprints were taken and it was found that there were no legal problems. However, I was transferred with 50 other young men from Gaziantep to Harran camp, where they told me that the other camps were full.”

At the Harran camp, Malik encountered approximately 200 young men, most of whom had legal papers but were in violation of laws related to setting up a home or working in a different state without permission. Some of them were awaiting trial despite having been released. Malik described the camp conditions as grim, citing contaminated water and inadequate food. Malik explained,

“Because we were not provided with healthcare despite our requests, we chose to be deported to Syria on the seventh day of our stay in the camp, on 8 July, through the al-Rai crossing. When I arrived in Syria, I visited a doctor in Afrin who told me that the illness in my body was due to contamination, which is poisoning of the skin and blood. We were only given two cans of small beans a day, along with half a loaf of bread and two glasses of water. Each glass contained only 200 ml, so we suffered severe malnutrition.”

The testimonies gathered for this report and recent incidents in Kayseri indicate that Syrian refugees in Türkiye are facing serious human rights issues. These include forced deportation, racist attacks, and neglect in detention centers. There is a significant disparity between Türkiye’s adoption of international agreements protecting the rights of refugees and the actual treatment of refugees.

Racist Street Attacks and Forced Deportations

In mid-June 2024, the husband of Syrian refugee Rama al-Abdullah was attacked by a racist while returning from work in the coppersmiths’ market in Gaziantep, Türkiye.[4] He was stabbed in the shoulder and taken to the hospital. After a week of stabilization, he completed his treatment at home. Rama al-Abdullah, a mother of three, shares her experience with STJ, saying,

“On 6 July 2024, I was rushing to the hospital with my child, who was having a severe diabetic attack, when a Turkish Immigration Service vehicle stopped me. At first, I ignored their request, but they caught up with me and arrested me. Despite my tears and explanation that my child’s life was in danger, they disregarded my pleas and asked for my identification papers. I could not present them, so one of the officers struck me with a plastic object on my back, causing intense pain, and I screamed. Other officers arrived and called for an ambulance for my child. After receiving treatment, my child’s condition stabilized within half an hour. Then, they took me and my son to the immigration vehicle, where they electronically fingerprinted me and informed me that my data had not been renewed. Despite my insistence that my papers were valid, I was detained along with other women and children. We were transported to the Bekand police station in Gaziantep and placed in communal and solitary cells.”

Rama added,

“On the morning of 7 July, we were taken to Shahid Kamil Hospital for a medical assessment. I asked for medicine for my child and told the doctors that I had been beaten, but they ignored me. We were then taken to Nizip camp, where we spent a terrifying night. On 8 July, we were taken to the Bab al-Salama border crossing, and I was deported to Syria despite having valid papers. I entered Syria and went to my friend’s house in A’zaz, while my husband and children remained in Gaziantep under my mother’s care.”

In another testimony, Khaled Al-Ali (a pseudonym),[5] has been a Syrian refugee in Gaziantep, Türkiye, since 2013. He explained that in 2017, he had an accident while working as an elevator installer. The accident resulted in the amputation of his foot and damage to his vertebrae, which left him unable to work. Khaled now relies on the support of his relatives and his sister’s income from her sewing job.

On 28 June 2024, a group of Turks conducted a racially motivated attack on Khaled’s neighborhood, smashing cars and shops owned by Syrians and throwing stones at the windows of houses. On this, Khaled recounted to STJ,

“At 8:00 p.m., I went out with my sister to sit at the door of the house and check on my neighbors. Suddenly, Turkish police cars spread out in the neighborhood and violently entered the homes of Syrians. When they reached us, they asked me if I was Syrian. When I said yes, they took my mother and siblings out of the house and ordered them to get on the buses. Three officers carried me and my wheelchair to the bus. Although I told them that I was injured and disabled, they did not respond. We were taken to the Yeşilvadi police station in Gaziantep.”

Khaled added,

“On 29 June 2024, Turkish authorities separated the detained Syrian families into groups. The first two groups were taken to Beyli camp in Kilis, while the others were sent to Oğuzeli camp in Gaziantep. The following day, a translator, accompanied by guards, instructed us to take a group photo and record a video expressing our voluntary desire to return to Syria. They threatened to beat those who refused. Despite explaining to the translator that I suffer from hemiplegia and have an amputated leg, he said, ‘Place your fingerprint here, or I will detain you and your family for a month.’ At 2:00 p.m., we were ordered onto buses, where we were handcuffed so tightly that our circulation was cut off. We were then taken to the Bab al-Salama border crossing.”

On 7 July, the Turkish newspaper Karar reported that authorities had transferred a Syrian family of six, which included elderly parents and two children, to a deportation center in Kayseri province in preparation for deportation, despite the family holding temporary protection cards. This action was taken after the family filed a complaint stating that their neighbors attacked them during the violence against Syrians in Kayseri. According to the newspaper, the neighbors threw stones at the family’s house. As such, the family was threatened with deportation due to the complaint they filed.

Türkiye Uses Syrian Refugees as a Bargaining Chip with Europe

Despite Türkiye ratifying several international agreements protecting refugee rights, many human rights reports confirmed severe violations of human and refugee rights on its territory. Earlier reports by STJ have documented instances of forced deportations of Syrians, including a wave of deportations in September 2023. Many of those deported had valid residency papers in Türkiye or belonged to vulnerable groups that should be protected.

Türkiye is a party to the European Convention on Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the 1951 Refugee Convention. The Turkish government denies forced deportations and describes its policies as “exemplary” in dealing with refugees. However, Syrian refugees continue to be subjected to racist rhetoric from opposition parties who use their presence as an electoral card, threatening to return them to Syria. This rhetoric has led to attacks and crimes that have not been impartially investigated.

According to the interviewed administrative official at the Bab al-Salama border crossing, refugees without temporary protection cards are issued one and revoked the same day at a designated deportation camp. Then, authorities force those refugees to sign voluntary return papers. These measures are often taken to increase the number of revoked temporary protection card holders, preventing them from settling their status in the future. This is happening despite the fact that Türkiye has suspended the issuance of temporary protection cards; this action aims to increase the numbers provided to the European Union and the United Nations. In 2016, the European Union and Türkiye reached a migration agreement to stop the flow of irregular migrants to Europe by supporting their settlement in Turkish territory. Since 2011, Türkiye has received around €10 billion ($10.8 billion) from the European Union to help refugees and host communities.

Syrian refugees are facing harsh policies in Türkiye that ignore the humanitarian and legal conditions meant to protect them. These violations are not isolated incidents but part of a broader pattern reflecting the increasing social and political tensions towards refugees in Türkiye. These tensions are exacerbated by political discourses that vilify refugees and use them as pawns in domestic and foreign policy.

_____________________________________________________________________

[1] The witness was interviewed online by an STJ field researcher on 10 July 2024.

[2] The witness was interviewed online by an STJ field researcher on 9 July 2024.

[3] The witness was interviewed online by an STJ field researcher on 9 July 2024.

[4] The witness was interviewed online by an STJ field researcher on 12 July 2024.

[5] The witness was interviewed online by an STJ field researcher on 13 July 2024.

[1] The witness was interviewed online by an STJ field researcher on 8 July 2024. He requested anonymity for security reasons.