Introduction

Since early 2022, the Turkish government has been enforcing harsher persecution and deportation measures against asylum seekers, especially Syrian refugees, arbitrarily detaining hundreds of them.

Along with these measures, Turkish authorities engaged in a chain of refoulement against Syrian refugees, arbitrarily returning thousands to deadly Syrian territories.

Some of the forcibly returned had in their possession legal documents that entitle them to stay in Turkey, including a kimlik (Temporary Protection Identification Document).

Both the anti-refugee measures and the illegal returns corresponded to a fresh set of policies led by the Turkish government to restrict the influx of asylum seekers. These policies include the government’s announcement that they will not immediately grant Syrians newly entering Turkey the Touristic Residence Permit. Instead, the newcomers will be first relocated to collective camps and be subjected to status “checkups”.

However, against the Turkish government’s claims that these policies are exclusively concerned with newcomers, testimonies obtained by Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) confirm that hundreds of Syrian refugees were transferred to these camps even though they do not belong to the target groups. The presence of encamped refugees in Turkey pre-dates these policies, and several refugees subjected to these new proceedings have been in the country for long durations of time, which should have made them illegible for the checkups.

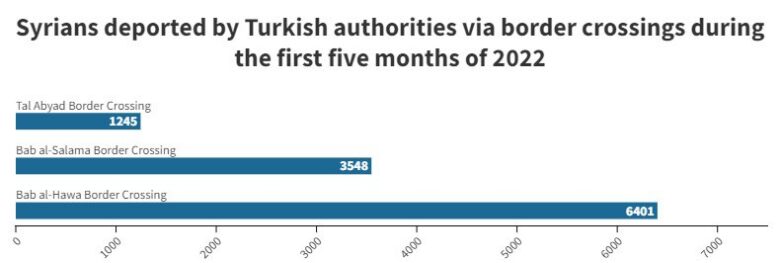

STJ traced the effect of these measures, compiling official figures published by the administrations of Syria-Turkey border crossings, mainly Bab al-Hawa, Bab al-Salameh, and Tal Abyad. STJ found out that approximately 11,000 Syrian refugees were forcibly returned in early 2022. Notably, the reported number does not include asylum seekers captured and returned while attempting to cross the border strip into Turkey illegally.

Monitoring the large-scale deportations, STJ published a lengthy report citing several testimonies and extensive evidence that corroborate the forcible return of over 155,000 Syrian refugees between 2019 and 2021.

This report was backed by another, documenting a new wave of refoulement at the onset of 2022.

Notably, several non-Syrians were deported to northern Syria, including persons who arrived in Turkey either seeking asylum or merely a transit location on their way to Europe. In August 2021, Turkish authorities deported 57 asylum seekers from Iraqi Kurdistan and nine Iranians to Azaz city, north of Aleppo. The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) was able to repatriate their citizens after several days, while Iran announced they managed to return their nationals on 1 January 2022, nearly three months after they were sent to Syria. Additionally, the Turkish authorities deported four Afghan asylum seekers to Idlib province in March 2022.

The deportation of non-Syrians confirms the arbitrariness underlying the application of Turkish measures, especially since several of the deported foreigners attempted to communicate with Turkish forces in charge to convince them they are not Syrians, but to no avail. The forces refused to listen or respond to their demands.

Strict Turkish Measures

On 11 June 2022, the Turkish Minister of Interior, Süleyman Soylu, announced that the government is opting for a strict package of measures against migrants in general and Syrian refugees in particular.

These measures include a foreigner residence limit in Turkish provinces, curtailing the percentage of non-nationals from 25 to 20 percent per neighborhood, and thus increasing the number of closed neighborhoods from 781 to 1200 across 54 provinces. Closures mean that foreigners will no longer be granted residence permits, including Syrian refugees.

In addition to residence restrictions, the Turkish government imposed navigational measures. Taxi drivers are granted authorizations to ask foreigners for proof of legal residence and travel permits. This regulation is purportedly set up to prevent the transportation of illegal immigrants.

In addition to neighborhood closures, minister Soylu said that [Turkey] is seeking to control the immigration flow. Syrians recently arriving in Turkey and wishing to remain there will be transported into a camp in Hatay province to examine their status.

The examination does not apply to Syrians traveling from Damascus, who will be immediately denied asylum or residence permits and returned to Syria.

Sources that STJ interviewed for the purposes of this report said that the Turkish government had designated several camps for detaining Syrian asylum seekers. The camp system is concentrated south of the country, including three camps in Kahramanmaraş, Urfa, and Kilis.

Protests in Maraş Detention Camp

On 16 June 2022, Syrian refugees held in the Maraş Camp, constructed in Kahramanmaraş, in southern Turkey, embarked on a protest against the ambiguity of the detention and deportation measures. The protest was dispersed by riot police and camp guards, who used water cannons and tear gas.

STJ obtained a first-hand account of the protest from a detained refugee:

“I used to live in Esenyurt area. On my way to work, the Turkish police stopped me and asked for my kimlik. I do not have a kimlik. So, they arrested and transported me to Tuzla center with nearly 40 other men. Two days later, they relocated us to Kahramanmaraş Province on board buses, protected by police. We were held at the Maraş Camp. They said that we will remain in detention while waiting for our turn to do the interview that decide what will happen to us. We are either allowed to stay and are granted a kimlik, or deported to Syria. During our stay in the camp, they brought in women and families as well. The number of detainees increased to over 1,500 persons. The conditions in the camp are poor. We get food, clothes, and medications at our expense. A car brings us the things we order. A large number of people did not have money, so they chose deportation to Syria due to the constraints.”

The witness added:

“The upheaval started when a young Syrian man began discussing the measures with the guards, saying they do not make sense. As they talked, the guards gathered and began beating the young man. In response, a number of young men tried to rescue him from the guards, who fired their arms in the air to disperse them. Then, several men attacked the guards and took two rifles. However, they immediately returned the rifles to the guards and the situation settled down. Then, we were surprised by the Riot Police. They entered the camp and fired tear gas and rubber bullets and opened water cannons on us. The clashes continued for two hours until the police withdrew and calm returned to the camp.”

On 16 June 2022, the governor of Kahramanmaraş addressed the protests in a statement: “Some disturbances erupted at nine (last evening, Wednesday) among a group of Syrians who were transferred to the Kahramanmaraş makeshift center. The security units intervened and took necessary measures. Calm was restored to the camp, and there are no problems now.”

Osmaniye Camp Is No Better

The Turkish authorities enforced similar constraints in Osmaniye Camp as in Maras Camp. Struggling in the woes of their uncertain fate, a group of Syrian refugees fled the camp.

The Turkish security forces in the city were mobilized and started searches for the escapees until they were all detained.

Several of the refugees were injured in the violence that accompanied the search operations.

Commenting on the incident on Twitter, the office of the Osmaniye governor said: A group of foreigners fled the Cevdetiye Makeshift Center yesterday, on Friday evening. The security and Gendarmerie intervened and brought the situation under control. They captured all the escapees, amounting to 35 persons.

In a related context, STJ documented an assault by Turkish citizens on escaping refugees before they were handed over to authorities and returned to the same camp.

Thousands of Refugees Deported Since Early 2022

Official figures posted by border crossings administrations reveal that the Turkish authorities have deported over 11,000 Syrian refugees since the beginning of 2022.

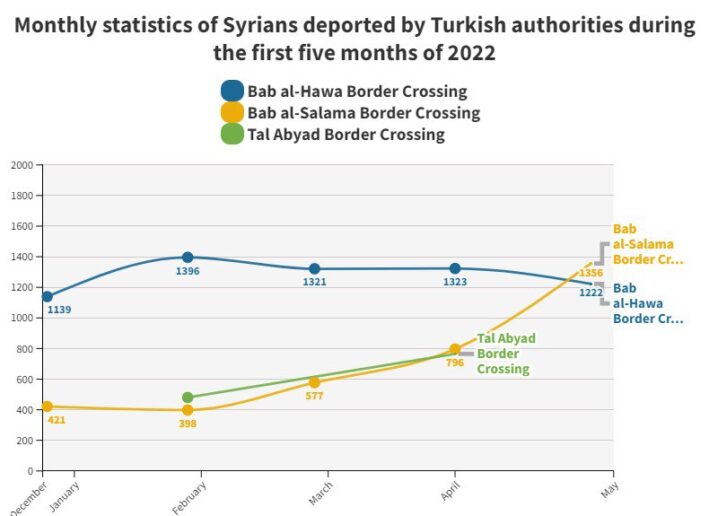

The deportations were carried out through three border crossings, with Bab al-Hawa crossing in Idlib witnessing the highest traffic, followed by Bab al-Salameh in Aleppo, and Tal Abyad in Raqqa.

Through Bab al-Hawa crossing, Turkey deported 6,401 Syrians in early 2022, with 1,139 returned in January, 1,396 in February, 1,321 in March, 1,323 in April, and 1,222 in May.

Through Bab al-Salameh crossing, 3,548 were deported, with 421 returned in January, 398 in February, 577 in March, 796 in April, and 1,356 in May.

Through Tal Abyad crossing, 1,245 were deported, with 480 returned in February and 765 in April. The crossing did not post figures relevant to the remaining months.

Conclusion

Restrictions against Syrian asylum seekers, particularly in Turkey, intensified over the past two years and were enforced in various forms, mainly:

- Limiting access to kimliks to provinces specified by the Turkish government. The Turkish government alleges that this regulation functions to ensure that refugees are distributed across all Turkish provinces, rather than centralized in certain ones.

- Hampering refugees’ access to kimliks. The Department of Immigration assigned an online portal for kimlik application dates. The portal poses language and technical challenges. While the larger number of refugees are not proficient in Turkish, the link to the portal is mostly dysfunctional. Refugees repeatedly try to apply for appointments and fail. Only a little segment succeeds in making reservations themselves after long periods spent waiting for the link to work, while brokers manage to make reservations over one or two hours.

- Giving refugees far appointments, knowing that issuing a kimlik is a two- or three-stage process. Refugees might wait for a period between three and nine months to obtain a kimlik or a certified document—a document showing all refugee-related information and valid for a single month. During the wait, refugees are denied access to allocated healthcare services, cannot rent a house, or subscribe to water, electricity, or gas.

- Freezing kimliks. In March 2022, the Turkish government deactivated thousands of kimliks held by Syrian refugees without prior notice. The Department of Immigration sent these refugees text messages informing them that their kimliks were dysfunctional for passing the deadline set up for home address updates. The department demanded they update the requested information even though several of the message recipients had already updated the data within the deadline.

These restrictions forced Syrian refugees to pay brokers exorbitant amounts of money, a minimum of which is 100 USD for officially registering their residential address and over 600 USD for obtaining a kimlik.

The high costs paid to brokers remain beyond the financial capacity of the majority of refugees, rendering them vulnerable to deportation under the recent intolerant governmental regulations.