Simav Hesen, QAMISHLI — Up until March 2023, Marwa, 30, had a routine. Every week, she and her sister took turns collecting water from a public tank in Hasakah city’s al-Nashwa neighborhood and carrying it home. That only changed after she experienced an incident of harassment.

Last March, Marwa set out to collect 100 liters of water—the quota for each household in her neighborhood—from the tank, which is filled by an international relief organization to provide water free of cost.

Marwa had carried the first 50 liters home and returned to the line of waiting women when the monitor, an employee assigned by the organization to supervise distribution, approached her and told her to “make way” for others because she already took her share, she recalled. She explained to him that she could not carry the full amount in one trip.

Continuing to wait, “I felt as though the monitor was trying to stand uncomfortably close to me. Then he caressed my hand,” Marwa told Syria Direct. Considering the incident “sexual harassment,” she “left and returned home, without getting the second batch.”

Marwa, like other women in Syria’s northeastern Hasakah city who were interviewed for this report, asked to be identified by her first name only.

Standing in line for water provided by humanitarian organizations or paying out of pocket to private water truck drivers is a feature of life in parched Hasakah city. For years, Turkey and the Syrian forces it backs have used water “as a weapon” by manipulating the flow of water from the Alouk water station in Ras al-Ain (Serekaniye), which pumps water to Hasakah.

In October 2019, Ankara and opposition Syrian National Army (SNA) factions launched Operation Peace Spring, targeting areas controlled by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). The attacking forces ultimately took control of Ras al-Ain (Serekaniye) in Hasakah province and Tal Abyad in Raqqa province.

With opposing forces in control of Hasakah’s water supply, a new task fell on the shoulders of women and girls in the SDF-controlled city: collecting water from public tanks distributed by humanitarian organizations as an emergency solution.

It also left them vulnerable to harassment and exploitation. An overview of gender-based violence in Syria, published by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) in early 2024, linked elevated incidents of sexual violence to water, sanitation and hygiene facilities, including toilets, bathing sites and water points.

During visits to four Hasakah neighborhoods—Gweiran, al-Nashwa al-Gharbiya, al-Mushayrfa and Khashman—where residents rely on public tanks for drinking water, Syria Direct spoke with women and girls who were transporting water for distances ranging from 10 meters to more than 100 meters.

When directly interviewed, women complained about many situations that arise when collecting water, including arguments breaking out in lines and restrictions on the quantity of water, but avoided mentioning whether they faced harassment, as in Marwa’s experience.

However, women in the Gweiran neighborhood said they do not allow unmarried girls to carry water to avoid indecent looks or catcalling in the streets, as one told Syria Direct. One 19-year-old said she only began fetching water after she married. “It’s a task for married women,” she said, without explaining further.

In the Khashman neighborhood, residents said women and girls alike “transport water from the tanks to their homes, but only after making sure the tanker driver and the organization’s monitor have left.”

Alongside field visits, Syria Direct surveyed 50 women in Hasakah city about their experiences. The questionnaire included a way to get in touch with the reporter, and many sources reached out to speak about their experiences.

Harassed by monitors

Three kilometers from al-Nashwa, where Marwa lives, residents of Hasakah’s al-Askari neighborhood wait for Monday every week, when public water tanks are filled.

Layla, 28, and her brother take turns fetching water and carrying it dozens of meters from the neighborhood tank to their home. One day, when she was about to leave her house, she happened across the local monitor employed by the organization providing water to al-Askari standing outside her door, she recalled. The man approached, asking if she lived in the neighborhood. When she replied that she did, he said “we will move the tank closer to your house,” she told Syria Direct.

Feeling that the monitor was overstepping, Layla pretended to call her brother, “so he turned around and walked away,” she said. She thought the incident was over, but when returning home from work a week later she found the tank had indeed been moved closer to her house. “It was an ugly feeling, the ugliest, when I saw the tank nearby,” she said. “What is the fault of the people [who would now be farther from it]?”

Since then, Layla takes precautions, only fetching water at the last minute and waiting for “the organization’s monitor to leave,” she said. She fears her brother could “create a problem if he picks up on the employee’s words.”

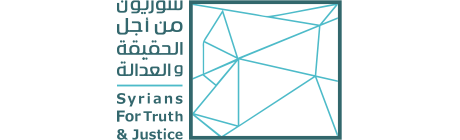

Of 50 women between the ages of 18 and 25 surveyed in Hasakah city and the nearby Serekaniye and Washokani displacement camps—also impacted by the water crisis—36 percent said they experienced “uncomfortable” comments from water service providers.

In Washokani, where people displaced from Ras al-Ain (Serekaniye) live, three women said they had faced “verbal harassment,” recalling phrases such as: “I’m interested,” “don’t you want me?” and “do you have a phone number?”

The results of Syria Direct’s survey intersect with what the Hasakah-based Salam Organization found when it conducted a risk assessment of women’s access to water, reaching 120 women and girls through its mobile awareness team.

“Thoughtlessness and a lack of oversight of the monitors” could be “a reason for the harassment and this treatment of female beneficiaries,” Aisha, 27, a displaced teacher from Ras al-Ain (Serekaniye) said. “The monitors working with the organizations ask many personal questions, such as: Are you married? Do you have a contact number?”

“There is exploitation and harassment of women and girls, especially the marginalized and economically vulnerable,” Daoud Daoud, Salam Organization’s chief executive officer, said. Increased water scarcity may “exacerbate these risks,” he added.

“When access to services is limited, the danger of sexual exploitation and abuse increases,” one protection specialist working with an international network implementing programs in northeastern Syria said. She declined to disclose whether her organization has received complaints of sexual exploitation or harassment tied to accessing water.

Exploited by water truck owners

Exploitation, in the context of the water crisis in Hasakah and other parts of Syria, is most often discussed in terms of price gouging. While the cost to fill a 30,000-liter water truck is around 25,000 Syrian pounds ($1.70 at the current black market exchange rate of SYP 14,560 to the dollar), customers in Hasakah buy 5,000 liters of water at a cost of SYP 35,000 ($2.40), three times what it cost in the summer of 2023.

For many women, exploitation takes another form: sexual exploitation and demands for services in exchange for water, as sources in Hasakah told Syria Direct.

The United Nations (UN) General Assembly, in Resolution 64/292 of July 2010, recognized “the right to safe and clean drinking water and sanitation as a human right that is essential for the full enjoyment of life and all human rights.” The UN Human Rights Council reaffirmed this right in Resolution 15/9, explaining it “is derived from the right to an adequate standard of living.”

Hasakah families spend an average of SYP 210,000 ($13.35) each month on water, filling 5,000-liter tanks six times. Each refill meets the needs of a family of five for around five days. Residents served by organization-funded public water tanks also occasionally purchase private water as needed.

In February 2024, after buying water from a private tanker, Layla began receiving phone calls after midnight from the seller. When she did not respond, he sent a voice message, she recalled, saying: “I only charged you SYP 10,000 for the water. Answer me.”

Layla said she had paid full price, and called the seller the next day to inquire further. He asked her if she was from a particular neighborhood, and when she told him he had the wrong person, “he apologized, saying he had the wrong number,” she said.

She accused the seller of “exploiting women’s need by offering water at a lower price in order to ask them for other services.”

Before that incident, Layla had to change her phone number after she was harassed by another water truck owner, who repeatedly tried to call her from different numbers and asked her to meet with him outside, she said.

Another woman surveyed for this report also said she was harassed by a water seller. He went as far as to suggest, instead of payment, to “spend an evening with you” or visit her at home. He also sent messages asking for pictures of her, alongside explicit sexual requests, she said.

Anas Akram, who works mornings distributing water to public tanks for one organization, then sells water in the afternoon, confirmed that some sellers exploited women. He cited conversations between water sellers while filling their vehicles, in which some openly discussed “providing water for free in exchange for spending time with the customer,” he said.

“The exploitation of women by water providers results from several factors, including socioeconomic discrimination and a lack of necessary oversight and legislation,” Rima al-Kalib, a social worker at the PÊL-Civil Waves organization in Hasakah city, said. Daoud, of Salam Organization, pointed to “a lack of awareness, and the fragile economic situation.”

In an effort to alleviate the city’s water crisis, the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) has implemented a project to draw water from the Euphrates River to Hasakah. Experimental pumping began in July, targeting the Gweiran, al-Zuhour, al-Aziziya, al-Talaea, al-Salhiya, al-Mufti neighborhoods, as well as part of Khashman, the AANES-affiliated Hawar News Agency reported.

Women in Gweiran interviewed for this report said water from the new project arrived only for a few days in July, then stopped.

The committee monitoring the Euphrates water project attributed the outage to encroachments along the 60-kilometer water line, as committee member Adnan Khaled told local independent radio station ARTA FM. Some 15 encroachments along the line had been found, he said.

A map shows the neighborhoods of Hasakah city reportedly targeted by the AANES project to pump water from the Euphrates River to the al-Aziziya water station (Wikimapia)

Barriers to reporting

In May, Aisha worked as a water distribution monitor in Washokani camp on a 20-day contract with an international relief organization. Her job consisted of monitoring, alongside an escort, the filling of water tanks in one sector of the camp by contracted tanker drivers and returning to an assembly point once all were filled.

One day, when her work was complete, she boarded the last water truck to return to the assembly point. “When I got into the car next to the escort, I felt his hand pulling my hand towards him,” Aisha said. “I pretended not to notice, thinking he didn’t mean it. But before I got out, he pinched my thigh.”

Organizations providing water in Washokani train monitors and water distributors in women and children protection policies, Aisha said. Monitors also sign a code of conduct that includes conditions stating they will be fired if it is violated. Water truckers are accompanied by an escort and monitor to ensure the tanks are filled completely, to prevent water being stolen or sold by the contracted driver.

Aisha told her female colleagues what happened to her, but they advised her not to file a complaint against the escort “so he wouldn’t lose his job and livelihood,” she said. She complied, afraid of being singled out as they “faced similar situations and had not complained,” she said.

She did not tell her family either, given a social reality that blames the victim rather than holding the perpetrator accountable in most cases involving women. “They wouldn’t believe that I did not cause his action,” she said.

Unlike Aisha, Salma, 21, did file a complaint against one of the people responsible for distributing water in Serekaniye camp, located in Hasakah’s al-Talaea neighborhood, last summer. “The organization responded, fired him and hired someone else,” she told Syria Direct.

Salma had faced “a lot of abusive words from water sellers in the camp” before the incident that ultimately drove her to file a complaint. That day, she “was doing housework without wearing a hijab, and was surprised to find one of the people responsible for filling water peeping while on top of the roof of my kitchen,” she said.

“There is no culture of reporting among women in the camp,” Salma said. “However, from interacting with the organizations through trainings, I know that it is my right to file a complaint against a service provider if he harasses beneficiaries.”

Still, many are afraid to report harassment. “The very word ‘complaint’ scares me,” Marwa said. “What if I complain, and they cut off service to the neighborhood? Our household doesn’t have the means to buy water periodically.”

On August 22, the reporter contacted the regional director of the organization whose employee Marwa said harassed her to inquire about how well its complaint mechanisms align with Hasakah’s social reality, as well as about the protection mechanisms for women who file complaints and training procedures for service providers. The organization did not reply by the time of publication.

An internal source in the organization later said that it rejects any allegation that any of its monitors harassed or sexually exploited beneficiaries.

The protection specialist, interviewed over Zoom, said her network has been advocating since last year for the use of complaint referral pathways between service provider organizations joining it on the basis of a “community complaint mechanism,” relying on local organizations operating in the region.

“While the network works to support humanitarian organizations and points of contact concerned with protection from exploitation, extortion and sexual harassment to ensure internal reporting and effective investigative procedures adhering to universal principles, it is not responsible for complaints and does not investigate them,” she said. Looking into individual reports “is the responsibility of the organization or humanitarian entity that employs the alleged perpetrator and is therefore responsible for these actions.”

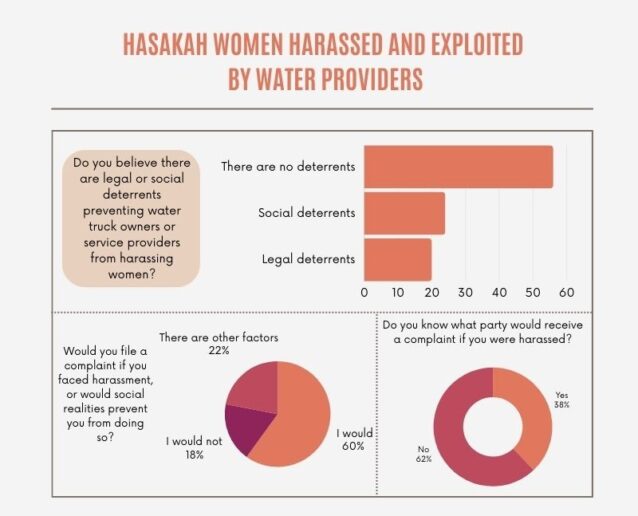

In neighborhoods where residents rely on public water tanks supported by organizations, women Syria Direct spoke to said they did not know what party to complain to if they were harassed, and had not received any information about how to do so.

It is also noteworthy that no phone number to call to make a complaint is circulated among residents or written on water tanks in Hasakah neighborhoods.

When asked, one woman in Khashman said she might complain to the owner of the house the water tank was located in front of.

Of 50 residents surveyed, 30 said they would file a complaint if they faced harassment. However, eight of them added comments indicating reluctance, including: “Someone would prevent me,” “I don’t know the authorities responsible for complaints,” “there is no swift response to complaints,” “there are social factors that stop me,” “I don’t know where to complain,” “customs and traditions would stop me,” “personal weakness and a poor financial situation are a barrier” and “fear of family, customs and traditions.”

The participants’ comments intersect with the views of those who said they would not report harassment. Some cited social factors and fear of the reaction of family members or husbands, while others said they did not trust that the relevant authorities would hold perpetrators accountable. “There is a fear of a problem happening, since the tanker owners are from here,” as one wrote.

“Not all organizations providing water services follow an approach based on raising awareness of mechanisms for reporting and complaints, and not all of them publicize protection measures,” Daoud said.

“Women may not be aware how to use available complaint mechanisms, or may not be aware of their rights,” al-Kalib added.

Efforts by civil society organizations and local authorities to protect women consist of “providing nearby water points, distributing water through tanker trucks and raising community awareness,” Daoud said. “There is still a shortage of funding and resources to scale up these interventions sufficiently to cover all areas at risk.”

Commenting on that, Bassam al-Ahmad, the executive director of Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ)—which collaborated with Syria Direct to produce this report—said “providing emergency response in basic services does not negate the need to simultaneously circulate protection [measures] to prevent harassment and exploitation.” “The commission of violations should not be justified by the severity of people’s need for the service.”

Al-Ahmad attributed harassment to an “absence of clear legal frameworks, complaint mechanisms and accountability for the perpetrator in a framework of promoting fairness and justice,” noting “the local authorities are directly responsible for protecting women.”

Article 308 of the AANES’ Penal Code, issued in 2018 and amended in May 2023, punishes those convicted of sexual harassment with imprisonment for between six months and two years, as well as a fine of SYP 500,000 (around $34).

The punishment under the Syrian Penal Code is lighter—three days’ imprisonment or a fine not exceeding SYP 75 (less than $0.01)—as stated in Article 508. These are “very light penalties for sexual harassment (verbal or physical), and are not commensurate with the seriousness of the act,” al-Ahmad said.

He emphasized the need to “conduct awareness campaigns through various available means, especially for women, through the media, workshops and others.” The AANES body responsible for water should also “meet with all tanker owners and water distributors and give them the necessary instructions in this regard,” he added, and threaten to “withdraw their permits in the event of violations of this nature.”

A complaint number should also be placed in a clear and legible place on every water tanker, with the owner obliged to do so, with an employee assigned to receive complaints and refer them to the relevant authorities, al-Ahmad said.

Because some organizations allocate resources to protect women and others do not, it is also necessary to “advocate with the donors to ensure that humanitarian and civil society organizations in particular allocate sufficient resources to protect against exploitation, extortion and sexual harassment,” the protection specialist said.

This report was produced in collaboration with Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) as part of Syria Direct’s Sawtna Training Program for women journalists across areas of control in Syria. It was originally published in Arabic and translated into English by Mateo Nelson.