On 14 September 2022, the residents of al-Mahatta neighborhood in Ras al-Ain/Serêkaniyê city discovered the dead body of a little boy, Yassin Ra’ad al-Mahmoud.

The Iraqi boy’s body was dumped in the yard of one of the neighborhood’s houses, not very far from the child’s residence.[1]

The forensic report concluded that the little boy had been brutally beaten, raped, and killed with a stone or a similar object.

On the same day, the Military Police of the opposition’s Syrian National Army (SNA), which shares control over the city with the Turkish military, arrested the murder suspect, Mustafa S.[2]

The next day, on the evening of 15 September, masked gunmen shot and killed the suspect in downtown Ras al-Ain/Serêkaniyê, while on his way from the Military Police Department to the Civil Police headquarters.[3]

The Military Police ordered the transfer of the suspect to the Civil Police headquarters after he confessed to committing the charges pressed upon him. The transfer order was the start of the case proceedings within local courts.

Notably, the extrajudicial killing of S. followed outrage and sweeping demands from locals to subject the suspect to Qiṣāṣ (a punishment analogous to the crime) in the hours after his arrest.

Moreover, while the identities of S.’s shooters remain unknown, several SNA commanders made statements to media outlets or on social media, indicating that the SNA killed the suspect without bringing him before court.

In this report, Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) investigates the murder of the little boy and the ensuing killing of the suspected perpetrator.

Following leads on the death of the suspect, STJ obtained the accounts of three informed sources, among them two SNA commanders. The commanders confirmed that S. was a former member of the Islamic State (IS) and that he entered the Peace Spring Strip— including Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tal Abyad, under the protection of The Northern Hawks Brigade, the faction that also greenlighted his access into the region.

Additionally, the sources stressed that commanders of several factions in the Liberation and Construction Movement (LCM) agreed to murder S. and that his death was planned in cooperation with the Military Police. They added that the decision to kill the suspect followed several fatwas (edict) from Sharia scholars within and outside the LCM, necessitating that he be killed publicly.

The Little Boy’s Murder

Inquiring into the murder, STJ reached out to a neighbor of the child’s family. The neighbor also lived close to the suspect and was among the people who reported the murder to the police. On the condition of his anonymity, the neighbor narrated that the child used to play in the street with other children while his mother was out selling bread for a living. He added that the suspect was seen talking to the little boy in the days before the murder, which explains how he managed to easily lure him into his house.

The neighbor narrated how the body of the little boy was discovered:

“It was in the afternoon. We heard people in our street saying that they discovered the dead body of a little boy. The boy’s body was dumped in the yard of an abandoned house, and he was raped. With other neighbors, I went to observe the location. We noticed a trail of blood that stopped at [S.’s] house. We knocked on his door and asked him to let us in. He refused. Therefore, we called the Military Police, and they showed up right away. Several fighters of the Northern Hawks Brigade accompanied the police. They scanned the house and discovered traces of blood near the sewage drain. S. confessed that he raped and killed the child and that he dumped his body and returned home to clean it up.”

The neighbor’s testimony corroborated the heartbreaking account of the little boy’s grandfather. In a video shared by local media outlets, the grandfather narrates that Yassin was late in returning home. So, he went out to search for him. He found a trail of blood on the ground, which led to the location of the boy’s dead body. The body was taken to the hospital. The doctor that examined the body revealed that he was raped before he was hit to death by a stone or a similar object. The Military Police came, examined the location of the dead body, and followed the blood trail up to S.s’ home, who immediately admitted to killing the child after raping him.

STJ contacted a commander of the Military Police. The officer recounted:

“When the people reported the crime to us, we headed to the location where the dead body was discovered. We followed the blood trail and reached the house of [S.]. He confessed to the murder. The man was under the protection of the [Northern Hawks] Brigade. However, the brigade did not protest the arrest at all, because the case had to do with rape and because of the anger that had taken over the people in the city, not overlooking the fact that the region is governed by tribal relations.”

Brigade Protection

While covering the murder, several local media outlets traced S.’s birthplace to Soran town, in Hama Province.[4] Additionally, the outlets reported that S. was a fighter with IS and that he was captured by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) of the Autonomous Administration. He spent five years in SDF’s custody and had arrived in the Peace Spring strip only recently.

For further information about S., STJ talked to one of his neighbors in al-Mahttah neighborhood. He narrated:

“S. arrived in Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê city two weeks ago, in early September. He rented a house in the street where I live. He had two or three visits by four or five fighters from the Northern Hawks Brigade. He told us that he was a prisoner with SDF and that he was recently released. He was planning to travel to Turkey.”

A second officer from the Military Police confirmed to STJ that S. was a former IS militant and that he entered the Peace Spring strip under the protection of the Northern Hawks Brigade. The officer said:

“The SDF released S. upon mediation from tribes. [The Sheikh Najib] armed group, affiliated with the [Northern Hawks] Brigade, helped him move into the region. The group had him under their protection and identified him as one of their fighters. [Commander Sheikh Najib] was certainly paid to do so, because he runs a human smuggling point in the area. Common practice implies that we interrogate any civilian who enters our region. However, S. was introduced as a fighter, so the Military Police did not interrogate him.”

The SNA’s Role in the Suspect’s Murder

The Military Police commander STJ interviewed said that a military police patrol arrested S. from his house in al-Mahatta neighborhood on the evening of 14 September 2022. The patrol was accompanied by fighters from the Northern Hawks Brigade.

The commander added that masked gunmen killed S. in the evening of 15 September, as he was being relocated from the headquarters of the Military Police to that of the Civil Police.

In addition to the police commander, STJ talked to a military commander within the LCM. He said that the commanders of the Tajammu Ahrar al-Sharqiya/Gathering of Free Men of the East, the Eastern Army/Jaysh al-Sharqiya and the 20th Division agreed on the necessity to kill S.—especially after several sharia schools within these factions issued fatwas making S.’s death an obligation.

The commander stressed that the Military Police was informed of both the agreement and the manner of the planned execution, adding that the police did not intervene to guarantee the safe transfer of the suspect on his way to trial.

The LCM commander also demonstrated the factional response to the child’s death:

“When the news about the little boy’s rape spread, evident anger spread over the fighters of the factions. They did not hide their desire to apply Qiṣāṣ to the perpetrator by executing him. To my knowledge, the commanders of the three factions [of the Tajammu Ahrar al-Sharqiya/Gathering of Free Men of the East, the Eastern Army/Jaysh al-Sharqiya and the 20th Division] referred to the sharia scholars [of the LCM] for an opinion. All the scholars necessitated the death of the perpetrator. Additionally, the three commanders asked for the opinions of sharia scholars from outside the LCM, including those working with the Northern Hawks and the Aharar al-Sham. These scholars offered them a similar answer. Therefore, there was a unanimous decision of the obligation to kill the perpetrator.”

The source added:

“The three commanders were not certain that the Military Police would kill the perpetrator, and were not satisfied with the only speculative life sentence that awaited him, worried that [S.] could either escape prison in the future or be released after paying money. Therefore, they informed the Military Police command of their intention to kill the perpetrator. The Military Police refused to hand him over to the commanders and thus an agreement was made that masked gunmen kill him on the way. Indeed, the Military Police patrol who accompanied the perpetrator was informed of the plan and of what was about to happen. The patrol remained on the sidelines and did not shoot at the gunmen when they intercepted them.”

He added:

“The commanders did not initially agree on declaring S.’s death. However, when news of the death spread , they made an announcement and claimed responsibility, saying that the SNA carried out the operation. They ordered the shooting and retaliation. With this, they garnered the support of the locals.”

After the death of S. went viral on social media, several SNA commanders posted the news on their official accounts and cited the SNA as the party behind it, including Abu Hatim Shaqra, commander of the Ahrar al-Sharqiya.

Image (1) – The tweet of Ahmed bin Issa al-Sheikh, the leader of the Suqour al-Sham Brigade, pleased with the killing of the suspect (The tweet was later deleted).

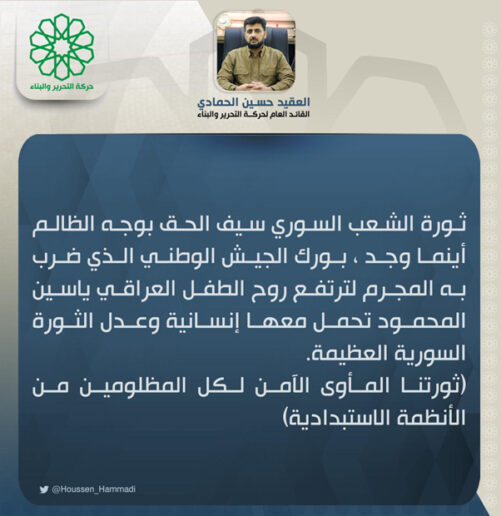

Image (2) – The statement of the Media Office of the Eastern Army congratulating the killing of the suspect. Published by Colonel Hussein al-Hammadi, the leader of the Eastern Army and the general commander of the Liberation and Construction Movement (Link to the original tweet, accessed on 08 November 2022).

Image (3) – The tweet of Abu Hatem Shaqra, the leader of the “Ahrar al-Sharqiya” and the deputy leader of the Liberation and Construction Movement. He admits that members of the National Army killed the suspect (Link to the original tweet, accessed on 08 November 2022).

Image (4) – The tweet of Jaber Ali Basha, the former leader of the Ahrar al-Sham Islamic Movement. He demands that the suspect be killed by crucifixion, outside the “delusional framework” of institutions. (Link to the original tweet, accessed on 08 November 2022).

The Suspect’s Death in the Law

Local Laws

The death of the suspect at the hands of the masked gunmen amounts to extrajudicial killing. Various factors play into categorizing the shooting of S. as a summary murder. First, the perpetrators are not law enforcement agents. Second, the suspect’s confessions before the Military Police did not make reliable and conclusive evidence of his perpetration of the crime of rape (sexual intercourse with a minor) and murder. To be considered, indicting confessions must be made before a specialized judicial body and be backed with sufficient evidence. Notably, the suspect was not brought before the court, which is supposed to assess and discuss available evidence and confessions and decide whether they are true or not.

Because no court was involved in the case, there is no proof that the Military Police did not extract the confessions by force and under coercion.

A third factor that cannot be overlooked, and which affects the integrity of the confessions and evidence referred to, is the suspect’s affiliation with the Northern Hawks Brigade. In this context, the confessions might have been fabricated by the brigade or another of the factions operating in the city to eliminate the suspect.

In addition to evidence and confessions, convictions are built on further investigation on the part of the specialized judicial body overseeing the case. Due procedures mandate that the assigned court investigates the merits of the case and the circumstances surrounding it to identify which legal frame to apply to the charges, considering the confessions relayed by the suspect are valid.

Investigating the intricacies of a case helps to properly characterize the criminal act and define the legal text applicable to it. For instance, if the suspect had planned the rape and subsequent murder, the suspect is then convicted of premeditated murder.[5] However, if the suspect resorted to murder after rape due to certain circumstances, the suspect is then convicted of homicide for an inferior motive[6]—having intercourse with a minor).[7] Such circumstances include the screaming of the victim or wounds or pain as a result of the rape, which threatens to expose the crime later, and thus the perpetrator killed the victim to obliterate the details of the crime of rape and to evade taking responsibility for it.

Regardless of all these violations of due procedures, passing and enforcing the death sentence against S.—had the factions given him access to a fair trial, remains beyond the scope of local courts. The courts, active in the Peace Spring strip, do not have the power to issue death sentences, because they have declared their commitment to the application of Syrian law. The Syrian law bans the enforcement of the death penalty unless the Special Pardon Committee (SPC) is asked to assess pertinent case files and give an opinion, and the president of the republic ratifies the verdicts issued. Both requirements cannot be met in the strip because it is outside the control of the Syrian government.[8]

Accordingly, since the death sentence is out of the question, the court, in the case it managed to convict S., should have opted for any of the imprisonment sentences prescribed by the Syrian Penal Code, including a life sentence.

Notably, the local factions counter-argument against the imprisonment, alleging that S. could have escaped or bribed his way out of detention, while it does not offer them grounds to kill the suspect, merely serves as evidence of their incompetence. This failure on the part of the factions has more dire repercussions when addressed under international legal frames.

International Laws

International humanitarian law (IHL), applicable during armed conflict, does not in principle prohibit non-state armed groups from issuing court rulings, including death sentences, against those convicted of criminal offenses. However, it sets strict and indispensable conditions so that these provisions do not turn into a violation of the IHL itself or amount to war crimes as defined by Article (8.2.c.iv) of the Rome Statute founding the International Criminal Court. The conditions are offered in Article common to the Geneva Conventions of 1949, which prohibits “the passing of sentences and the carrying out of executions without previous judgment pronounced by a regularly constituted court, affording all the judicial guarantees which are recognized as indispensable by civilized peoples.”

Notably, the non-prohibition aims to ensure an alternative to “summary justice” that exacerbates the suffering of people during and after the armed conflict. Therefore, the Additional Protocol II of 1977, in Article 6(2)—which reflects customary IHL—elaborated on the conditions of the trial. The article recentralized the legality of issuing sentences not in the requirement that the court be “regularly constituted” but rather in the requirement that the court provides basic guarantees of independence and impartiality, which in the context of a non-international armed conflict is at the heart of the interpretation of the court’s regular formation requirement.[9] These guarantees are what make the trial fair and thus the logical antithesis of the summary justice IHL seeks to counter.

Additionally, the parties to the conflict bear the responsibility to ensure that sentences are issued only through impartial and independent courts that can actually provide the offender with fair trial guarantees. These guarantees include the offender’s access to the necessary rights and tools of defense, the observance of the principle that an offender is not judged except in accordance with the legal text that criminalizes the act and specifies its due penalty, that the trial shall take place in the presence of the offender, and the presumption of innocence.

Moreover, the requirement of judicial independence entails that none of the procedures against the suspect, from arrest to sentencing, be subject to official or popular influence. The party responsible for forming the judicial body bears the responsibility that this influence does not fall on the court.

Furthermore, military commanders of non-state armed groups during armed conflict bear command responsibility if they knew or should have known that their subordinates have committed war crimes and did not hold them accountable. Similarly, the commander may be held criminally liable if he does not enforce the judicial system in his control to hold perpetrators accountable for war crimes.

In the context of the case under study, the armed groups involved in the execution denied the suspect access to a minimum of judicial guarantees. This qualifies S.’s extrajudicial killing to be a war crime of willful killing, within the perspective of Article (8.2.c.i) of the Rome Statute, which builds on the prohibition in Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions. This act, which may amount to a war crime, requires the responsible commanders of the armed groups involved in the case to take immediate measures to hold the shooters accountable.

Finally, the right to a fair trial for all suspects equally and without discrimination is a human right enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights “Everyone is entitled in full equality to a fair and public hearing by an independent and impartial tribunal, in the determination of his rights and obligations and of any criminal charge against him”. This right is also protected by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. In addition to the importance of combating impunity, STJ emphasizes that everyone shall be entitled to a fair and public hearing by a competent, independent and impartial tribunal established by law.

[1] “Al-Hasakah: The Rape and Murder of a Child Ignites Anger in Ras al-Ain” (in Arabic), Enab Baladi, 15 September 2022 (Last visited: 29 October 2022). https://www.enabbaladi.net/archives/604755

[2] “SNA Fighter Raped a Child and then killed Him” (in Arabic), Syria TV., 15 September 2022 (Last visited: 29 October 2022). https://www.syria.tv/182975

[3] “Mustafa Salamah: Murderer of Iraqi Child Yassin Killed in Ras al-Ain” (in Arabic), Syria TV., 15 September 2022 (Last visited: 29 October 2022). https://www.syria.tv/183121

[4] “Al-Hasakah: The Rape and Murder of a Child Ignites Anger in Ras al-Ain” (in Arabic), Enab Baladi, 15 September 2022 (Last visited: 29 October 2022). https://www.enabbaladi.net/archives/604755

[5] Article 535 of the Syrian Penal Code prescribes “the death penalty for homicide if it is committed: (a) Willfully”.

[6] Article 534 of the Syrian Penal Code prescribes “life imprisonment with hard labor for homicide if it is committed: for an inferior reason.”

[7] While local media outlets reported that the victim was 10-year-old, STJ could not verify this information to determine exactly which paragraph of Article 491 of the Syrian Penal Code applies to the case. The article provides that “Whoever has intercourse with a minor under 15 shall be punished with hard labor for nine years, and the penalty shall not be less 15 years if the minor is under 12.”

[8] Article 43 of the Syrian penal Code.

[9] See e.g., ICRC, Commentary of 2020, Convention (III) relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War, Geneva, 12 August 1949, § 714.