- This publication was funded by Legal Action Worldwide. Its contents are the sole responsibility of Syrians for Truth and Justice and do not necessarily reflect the views of Legal Action Worldwide.

Background

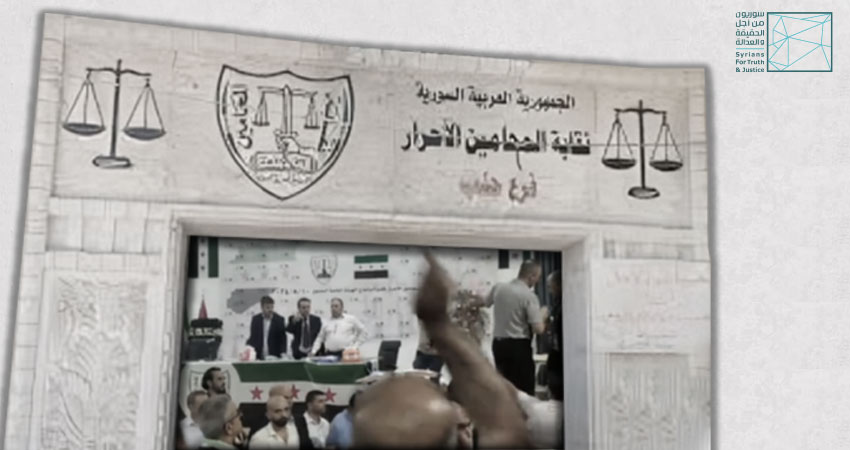

On 10 August 2024, a violent quarrel erupted during the meeting of the general assembly of the Free Bar Association, Aleppo branch, held in Afrin at the headquarters of the Turkish Gaziantep University. The main point of contention was the outcome of the July 2023 elections, which had been controversial due to concerns about their integrity, leading to a division within the Association. The meeting was disrupted by physical altercations and verbal insults among the lawyers, prompting police intervention to restore order. After the situation calmed down, the meeting resumed, and several decisions were made, including setting the date for the Aleppo Bar Association Council elections on 15 October 2024 and approving electronic voting.

Tensions arose when several lawyers questioned the legitimacy of the current council, alleging that it is supported by the Syrian Interim Government (SIG) and influenced by foreign powers. Meanwhile, others called for confirmation regarding the legitimacy of the elections. This conflict is part of a larger crisis affecting the Free Bar Association, particularly due to the SIG’s involvement in its affairs. These disputes reflect differing legal perspectives within the Association and are connected to the broader political tensions in northwestern Syria. In this region, the SIG seeks to bolster its authority and expand its influence, utilizing the military power of the Turkish occupation along with Turkish-supported factions of the Syrian National Army (SNA). Additionally, the SIG is trying to legitimize its control through electoral processes and organizational decisions.

The present paper summarizes conflicts within the Free Bar Association and the SIG’s interference in its activities. It also outlines the Turkish state’s responsibilities and discusses significant Syrian and international laws concerning the organization and independence of the syndicates.

The Free Bar Association in Syria was established in 2019 in response to the large-scale displacement operations conducted by the Syrian government during 2017 and 2018. Opposition lawyers recognized the need for an organization to coordinate their efforts and advocate for their rights. The Association was launched across nine governorates, including Aleppo, Homs, Hama, Latakia, Damascus and its countryside, Daraa, Raqqa, al-Hasakah, and Deir ez-Zor.

Disagreements and Divisions within the Association over Election Results

On 24 May 2023, the Central Free Bar Association issued Decision No. 32, setting the Aleppo branch council elections date for 24 June 2023. However, tensions escalated when the Aleppo branch, facing internal divisions, announced the postponement of the elections to 8 July 2023 and then again to 15 July 2023 due to the absence of some lawyers who were performing the Hajj pilgrimage.

On 9 July the Aleppo branch of the Free Bar Association issued Decision No. 210 to open four ballot boxes for the elections: a central box in the city of A’zaz, two boxes in the cities of Jarabulus and al-Bab inside Syria, and another box in Türkiye’s Gaziantep, as there are a significant number of Syrian lawyers in the diaspora. This decision was made after debates about using electronic voting, which some groups opposed in favor of physical voting with multiple ballot boxes. However, some lawyers objected to this distribution and insisted on using a single ballot box at the main Association headquarters in A’zaz to ensure the fairness of the electoral process.

In response to the ongoing dispute, several members of the Aleppo branch council and the Association’s general assembly announced their boycott of the elections scheduled for 15 July 2023. They cited repeated law violations by the acting council, such as setting up ballot boxes that contradict internal regulations and decisions of the General Conference and the General Assembly. Furthermore, lawyers pointed out that the council had exceeded its legal term, and its continued decision-making rendered it illegitimate. As a result, they refused to participate in the announced elections, although some later retracted their decision.

The elections took place as scheduled on 15 July 2023. Two main lists competed for the Association Council seats. The first list, led by lawyer Hassan al-Mousa, who was the head of the Aleppo branch, was called Renewal (Arabic: al-tajdeed). The second list, representing the opposition team, was called Integrity (Arabic: al-Istiqamah).

The results were almost equal when the votes in the two ballot boxes in A’zaz and Jarabulus were counted. However, the results changed utterly when the votes in the Gaziantep and al-Bab ballot boxes were counted. All members of the Renewal list won, except for one candidate from the Integrity list, lawyer Omar Tajan. This unexpected shift in the results raised doubts about the integrity of the elections, leading opposition lawyers to challenge the process and accuse the winners of manipulating the results.

After the election results were announced, the new members began their official duties. The only winner from the Integrity list stated that he would freeze his membership to protest the election’s conduct and results. This caused tensions to escalate, leading to several lawyers defecting from the Aleppo branch council to establish a new branch called the “Aleppo Countryside Branch.”

SIG Intervention Increases the Association Divisions

The SIG accepted the election results and supported the elected Aleppo Council. This has deepened the division among lawyers, with both rival branches calling for new elections for the central Bar Association in September 2023. As a result, two rival central bar associations have emerged: one led by lawyer Anwar Issa from the Aleppo Countryside Branch and the other by lawyer Mohammed Khair Ayoub from the Aleppo Branch.

The division between the two bars has further complicated the scene in northwestern Syria. This was especially true with the intervention of the SIG and its support for the central bar associations headed by Mohammed Khair Ayoub, which strengthened the latter’s legitimacy in the face of the Aleppo Countryside Branch. On 15 November 2023, the Ministry of Defense in the SIG issued Decision No. 308 to the Military Judiciary Administration. This decision stated that the powers of attorney from branches not affiliated with the bar association, headed by lawyer Mohammed Khair Ayoub, would not be accepted. This decision severely impacted the Aleppo Countryside Branch, leading to its officially unrecognized status and its inability to issue powers of attorney in the courts supervised by the SIG.

The measures taken led to increased tension within the legal community. Dissident lawyers from the Aleppo Countryside Branch organized open sit-ins to protest the SIG’s interventions. They called for an end to the crackdown on their activities and the recognition of their bar association as an independent legal entity.

In December 2023, lawyers Jamal Jassim, as a candidate for the General Conference of the Free Bar Association, and Saleh Abdullah, as a member of the General Assembly and a candidate for the elections in the Free Bar Association, filed an appeal before the Court of Cassation. They claimed that fraud had occurred in the elections. As a result, the court issued Decision No. 99 of 2023, which invalidated the elections of the Aleppo branch and dissolved the Aleppo Countryside Branch due to its illegitimacy. The court also decided to reinstate the previous council to manage the business until new elections were held.

On May 14, 2024, the Minister of Justice of the SIG issued Decision No. 29, which allowed for further intervention in the affairs of the Bar Association. This decision mandated the dissolution of bar associations that did not meet the required quorum and rendered their powers of attorney null and void. In response, opposition lawyers organized demonstrations and protests, especially after the Military Police Administration of the SIG supported the Ministry of Justice’s actions with a similar decision (Decision No. 189/S, issued on May 16, 2024).

The Aleppo branch council of the Association welcomed Decision No. 29; however, this sparked anger among other branches, subsequently issuing a statement objecting to the decision. They claimed it constituted an illegal interference in the Association’s affairs by an unauthorized party. The branches emphasized that the decision undermined the Association’s independence and rights. They also pointed out that the judiciary, represented by the Public Prosecutor, had approved this decision despite its apparent invalidity. The statement asserted that such powers belong solely to the Bar Association Council, per Article No. 46 of the Law Regulating the Legal Profession. Furthermore, the branches called for the rejection of this decision and demanded the complete independence of the Association, free from any governmental or judicial interference.

Unionism in Syrian Legislation

Since the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party took power in 1963, Syrian unions have lost their independence, especially after declaring a state of emergency. The government restricted their freedom and used them to strengthen control over various sectors. Instead of representing their members’ interests as free organizations, unions became linked to the Executive and the ruling Ba’ath Party. Union leaders were appointed based on the Party’s directives, and members were required to be part of the Party or support it, which turned the unions into tools for promoting government objectives and eliminated their ability to effectively represent the interests of workers. The government ought to legitimize this control by enacting several laws that stripped syndicates of their independence, making them part of the ruling regime’s institutional structure.

The current 2012 Syrian Constitution specifically addresses the issue of freedom of union activity in Article No. 10. It states that “Public organizations, professional unions and associations shall be bodies that group citizens in order to develop society and attain the interests of its members. The State shall guarantee the independence of these bodies and the right to exercise public control and participation in various sectors and councils defined in laws; in areas which achieve their objectives, and in accordance with the terms and conditions prescribed by law.”

According to the Constitution, the state is required to ensure the independence of unions, allowing them to operate freely without direct interference from the Executive or other authorities. The text above asserts that unions have the right to exercise public control and play a role in overseeing the government and participating in decision-making processes that affect the interests of their members. This reinforces the independence of union activities. The 1950 Constitution also affirmed the freedom of union organization, which meant that the SIG was obligated to uphold the freedom of union activities in the areas under its influence, as stipulated by the 1950 Constitution. This obligation arose from the government’s assertion that it would adhere to the Syrian laws in effect before 2011 as long as those laws did not contradict the 1950 Constitution.

Nevertheless, the 2012 Constitution allowed the government to control the work of unions and issue legislation that limits their work, as it asserts that the work of unions must be “per the terms and conditions specified by law,” which opens the door to legislation that limits this freedom. For example, Law No. 84 of 1968 on the Regulation of Unions and amendments granted the Executive broad powers to control the structure and work of unions. It imposed restrictions on how unions are formed and managed, which put unions under direct or indirect government control. The subsequent amendments to this law increased the Executive’s control over unions, as they stipulated that unions must comply with government policies, which led to them losing their original mission of defending the rights of workers or professionals.

In another example, Law No. 30 of 2010, Regulating the Legal Profession, treated the Bar Association as if it were one of the branches of the Ba’ath Party. It obligated the Association, in coordination with the Ba’ath Party’s regional leadership, to mobilize the masses to achieve the goals of the Arab nation (Article No. 4), which are the same as those of the Party.

The type of law discussed highlights how unions have become instruments of the Executive rather than independent organizations. It enables the Executive and the Ba’ath Party to interfere in union affairs and dictate their policies and directions. This situation contradicts the fundamental principles of union independence, necessitating unions to operate freely and make decisions without direct government intervention. Furthermore, this interference violates Article 10 of the Syrian Constitution.

Rather than canceling or amending laws to promote freedom of union activities per the standards established by relevant international covenants and charters or even implementing Article 154 of the current 2012 Constitution,[1] the Syrian authorities – including the Ba’ath Party – are attempting to introduce a unified legislative framework for professional unions. This approach undermines the independence of these unions and reinforces their subordination to the executive authority.

For instance, Article 48 permits the Prime Minister to dissolve the General Conference, the Council, or branch councils if any of these bodies “deviate from their tasks and objectives.” This opens the door to depriving the elected unions of their independence by allowing the executive authority to control decisions within the General Conference of the unions, effectively making them an administrative arm of the Syrian government.

Furthermore, the draft legislative instrument grants the State Council the power to adjudicate union disciplinary and conduct issues (as specified in Articles 39, 40, 44, and 52). However, the State Council’s jurisdiction traditionally extends only to public employees and individuals in similar roles in public bodies, not to unionists. By classifying unionists alongside public employees, this draft law fails to acknowledge their status as independent professionals, which is unacceptable.[2]

SIG Intervention and Türkiye’s Failure to Fulfill its Duties Threaten Unions’ Independence

International agreements recognize the right to form unions without interference or repression from the state or any ruling authority.[3] These agreements also guarantee the independence of unions, allowing them to be formed and managed freely and protecting unions and their members from discrimination based on their union activities. However, the SIG has violated these rights through its interventions, and we have outlined some details of these violations in this paper.

The SIG’s involvement in union activities directly threatens unions’ independence and their ability to represent their members’ interests freely and without pressure. This interference also undermines unions’ role in safeguarding their members’ professional and social rights, turning them into instruments for advancing the government’s agendas. These actions mirror the oppressive laws related to union activities in Damascus.

The independence of unions is crucial in any democratic system, as they play a vital role in ensuring that power is not concentrated in the hands of a few. Independent unions gain their legitimacy from holding free elections and safeguarding public and political rights. Therefore, the SIG’s meddling in the Free Lawyers Syndicate elections diminishes its ability to oversee those in power and uphold the rule of law, hindering progress toward genuine democracy.

It is important to note that the Turkish occupation authority has a dual responsibility for human rights in the northern Syrian areas under its control. It must avoid committing human rights violations in these areas and take adequate measures to prevent such violations by any other party, including the SIG. Therefore, Türkiye is responsible for safeguarding unions’ independence and their electoral processes in the northern Syrian areas where the SIG operates. According to Article 43 of the Hague Convention of 1907, Türkiye is responsible for maintaining security and order in the occupied territories, including protecting the independence of civil institutions, such as unions, from any military or political interference that could compromise their electoral integrity. Türkiye must ensure that these elections are conducted freely and fairly, without interference from supported local authorities or armed forces, and must prevent any political or military influences that could hinder the conduct of union elections or affect their outcomes. Furthermore, Türkiye must adhere to international standards, such as the International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention No. 87 of 1948, which guarantees freedom of association and the right to hold free elections. Türkiye can improve transparency by inviting international human rights organizations to oversee the electoral processes, thereby ensuring the independence of unions and protecting workers’ rights in these areas.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] The cancellation of Article No. 8 of the 1973 Constitution, which means that the Ba’ath Party is no longer considered the leading party of the state and society from a legal perspective. This change necessitates the amendment or repeal of all laws and regulations that grant the Ba’ath Party advantages over other political parties.

[2] For more information about the draft law, see: “Syria: A Draft Law for Professional Associations Strips Away their Independence and Strengthens the Power of the Executive Branch”, STJ, 29 August 2022;

or: “Syria: The Draft Law for Professional Associations is Still Pending”, STJ, 24 May 2023.

[3] See: Convention No. 87/1948 of the ILO (Article 2); Convention No. 98/1949 of the ILO; the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 23); the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of 1966 (Article 8); the European Convention on Human Rights of 1950 (Article 11); the American Convention on Human Rights of 1969 (Article 16).