On 25 January 2022, a video sent shockwaves across the internet, refueling the controversy over the large-scale property seizures the Syrian government (SG) is carrying out under the guise of urban planning and zoning projects. In the video, the local radio Ninar FM stops a woman on one of Damascus’ streets and asks her: “is the house where she lives rented or owned?”.

The question tore open a gate tightly shut on the suffering of several property owners in the Basatin al-Razi (al-Razi groves) neighborhood, adjacent to the facilities of the Syrian Council of Ministers. These owners were deprived of their properties under Decree No. 66 of 2012, which framed a new urban plan in the area, particularly the construction of “two zoned areas” in the southeastern part of Mazzeh and the southern parts of the al-Mutahlaq al-Janoubi (Southern Highway) in the capital Damascus.

The interviewed woman was one of these owners, she answered: “I had property, and they stole it from me!”

Agitated, the woman added: “I owned a house in the Mazzeh Bastatin (Mazzeh Groves) area. However, I was deprived of it. My house, the seven-star house, was seized”. She prided herself over her once spacious, well-constructed and furnished home.

She added:

“I invested every hard-earned penny to own a house in the Basatin area—the Mazzeh plots located behind the al-Razi Hospital. I am still confused, why would they, [referring to the SG-affiliated Damascus Province] authorize us to proceed with construction in the area, if there is a ban on housing construction there! Not to mention that we paid bribes to obtain building permits.”

The woman stressed that she paid those bribes in 1989, 32 years ago.

The woman continued her account, asking:

“Who is the entity responsible for my homelessness and property confiscation? My husband died from anger and bitterness over losing his property. We told Jamal al-Youssef [Director of the Zoning and Planning Department at the Damascus Province] that the law [referring to Decree No. 66] and the project execution are both untimely. We said that we are still living in a state of war and the country is nothing but a body of a struggling patient; can you do cosmetic surgery on the body of a sick patient? Is wartime the right time to reconstruct the country? This is madness, a sheer desire to displace average people, and to bring ruin on the sources of income of those who own small shops in the area and many of its people who live by the yield of the agricultural lands they have.”

The interviewer then asked the woman whether she was one of the owners whose properties were covered by Decree No. 66 of 2012.

The woman said:

“My house was within the [geographical scope] of Decree No 66 of 2012. Today, I am given a very under-valued annual rent compensation, of about 500,000 Syrian pounds (SYP)—the equivalent of 137 USD per year. After my husband died, the compensation, already very little, is being distributed to the heirs, leaving me only 100,000 a year, hardly 27 USD per year. This money, I have to say, barely covers my daily expenses given the acute rise in prices these days.”

The woman concluded:

“This is my country, my homeland, and I have rights here. Today, I live in a rented house of mud bricks, which is at the risk of collapsing over my head any moment! As if this is not enough, another zoning project is planned for the areas near the al-Muwasat Bridge, [where I live]. The project apparently will obliterate all houses in the area.”

Decree No. 66 of 2012

On 19 September 2012, SG President Bashar al-Assad issued Legislative Decree No. 66. The decree framed plans for the construction of “two zoned areas” as part of the master urban plan of Damascus city. The zoning was justified by the aim of “developing informal and squatter settlements” in accordance with the prepared detailed urban planning studies.

Article 1 of the decree demarcated the perimeters of the two zoned areas:

Zone One: An area southeast Mazzeh, constructed over real estates in Mazzeh and Kafar Sousah neighborhoods. Later, the area was called Marota City.

Zone Two: An area south the al-Mutahlaq al-Janoubi (Southern Highway), across plots annexed from Mazzeh, Kafar Sousah, Qanawat Basatin, Daraya, and Qadam neighborhoods. Later, the zone was called Basilia City.

The decree framed the two emerging cities with a set of regulations that differed from the relative and applicable zoning provisions of the Syrian Law, established in Law No. 9 of 1974.

Up to the issuance of Decree No. 66 in 2012, zoning projects in the target areas were subject to Law No. 9 which facilitated free confiscations of a third of the total area allotted for the construction of public structures.

In case the confiscations stretched to half of the designated area, Law No. 9 provided that concerned administrative entities pay compensation for the excesses. The compensation was to be defined at a later stage and according to the terms of the applied confiscation law.

Notably, unlike Decree No. 66, law No. 9 did not provide terms for “alternative housing” for those whose properties were confiscated.

The SG’s Hollow Justifications

SG officials claimed that the “zoning of these two areas” falls within the larger plans put in place for turning Damascus city into a financial and commercial hub, dictating that informal and squatter residential areas would be subjected to urban planning schemes.

To this end, the officials said that the Damascus Provincial Council (PDC) will reconstruct these areas, beautify Damascus, and cooperate with private companies by giving them construction permits.

However, the pretext on which the zoning plans are based remains contested, because there are various squatter residential areas, located close to the Mazzeh/al-Razi area, that continue to be unaddressed by the SG’s urban development projects.

The legal experts working with Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) believe that dedicating presumed zoning projects to some areas and ignoring others is grounded in the political affiliations of those areas. The experts posit that the SG excluded neighborhoods such as Mazzeh 86 from the zoning schemes and accompanying property confiscations because they are considered “pro-SG”, while neighborhoods in al-Razi and surrounding areas are labeled as “anti-SG” because they incubated non-governmental armed groups.

In addition to political affiliation, the SG has likely centered the zoning project in these areas because of their strategic geographical location within the capital. The two areas are adjacent to the Southern Highway which splits the capital’s southern strip from its northern one, without passing through the capital’s center. Apparently, the SG considers these areas the capital’s “first line of defense” against potential protests or military progress by anti-SG armed groups.

Violations of Property Rights Inscribed into Decree No. 66

Decree No. 66 was passed as an exception to the General Urban Planning Law No. 9 of 1974 which remained effective up to 2012.

Legal experts with STJ point out that the decree was likely enforced to enable the SG to confiscate the largest number possible of maqasims (sections of land and areas on which construction work has been done or will be done), and warrant the DPC to invest in the annexed areas “for free”, without clear confiscation criteria, top confiscation ceiling, or censorship.

Additionally, the decree enables the SG to designate several of the maqasims to the construction of public structures, such as places of worship, schools, and hospitals, annexing needed areas from the original owners’ properties without obliging executive entities to pay affected owners real or fair compensation.

The decree also provides the SG with legal grounds for relocating the residents of confiscated properties to alternative housing units, the value of which barely amounts to a quarter of the value of their original places of residence.

With extensive property appropriations, beyond the limits assigned by Decree No. 66, the DPC is committing a blatant breach of HLP rights, through which it continues to enrich the SG at the expense of original property owners.

The confiscations violate several property laws established across various legal texts. The seizures violate the operative Syrian Constitution of 2012, particularly Article 15, which provides for protecting public and private properties and prohibits confiscations without final court rulings.

The annexations warranted by Decree No. 66 also break Article 771 of the Syrian Civil Law, which states that no one is liable to be deprived of his/her property unless the seizure is carried out in line with the conditions set up by the law and the mechanisms it assigns, stressing that seizures should be implemented in exchange for fair compensation.

The terms of compensation put forward by Article 10 of Decree No. 66 are predatory. The article states that compensation must be worth the real value of the property before the Decree’s issuance date, ignoring any potential value increases effected by the decree and the zoning projects.

In other words, the DPC and their partners in private companies will appropriate homes and pay the owners little compensation, amounting to the pre-zoning prices. Then, the DPC and partners sell the properties by exorbitant after-zoning prices to people rather than the original owners, including investors. This is a legal breach and enrichment at the cost of the original owners.

Notably, the exploitative approach to confiscation and resale of properties is preceded by arbitrary value estimations of land plots and other properties targeted by confiscations.

Unlawful Confiscations

The Marota City project is an exhibition of unlawful property confiscations. The DPC manipulated the powers they are granted under Decree 66 and annexed large swathes of property, designating the confiscated plots to the expansion of the facilities of the Council of Ministers, the new building of the People’s Assembly, and affiliated administrative structures.

There is a twofold violation in these confiscations. First, the annexed properties are unauthorized by Decree No. 66, stretching beyond its scope. Second, the to-be-expanded structures do not fall under the label of public structures, as made clear in Opinion No. 133 of 1964 by the Advisory Department of the State Council:

“Public structures do not include buildings designated for official departments because these buildings are not municipal properties, nor are subject to municipal authorities; rather, they are state properties and are subject to special legal provisions.”

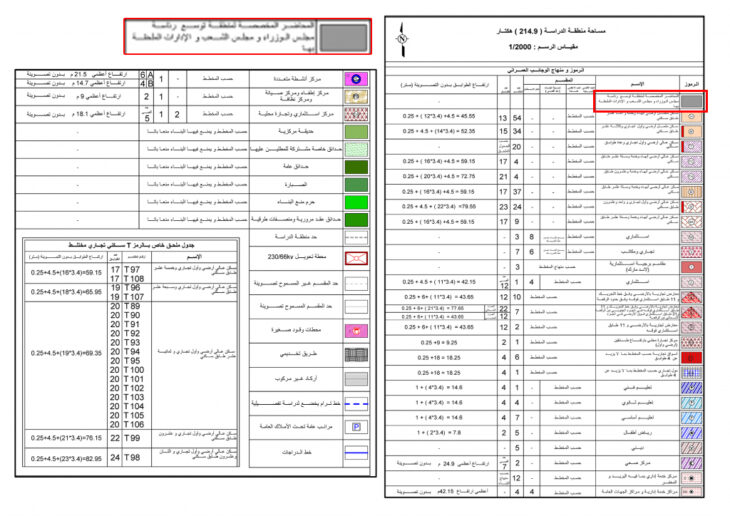

Image (1)- Copy of the design plan of Marota City and the distribution of its property sectors. In the top right corner, colored grey, are the plots of land confiscated and designated for the expansion of the facilities of the Ministers Council, People’s Assembly and their affiliated departments. Credit: The city’s Facebook page.

Image (2)- Copy of the urban schemes and sectioning of the Marota City, including codes and regulatory urban instructions. Credit: The city’s official page.

Alternative Housing Controversy under Decree No. 66

The decree obliges the DPC to provide entitled occupants within the to-be-zoned area with alternative housing, offering them compensation amounting to the value of an annual rent until they are handed the housing units.

Alternative housing is ratified by a decision from the Minster of Public Works and Housing.

However, the entitlement criteria inscribed into the alternative housing pertains only to occupants present within the to-be-zoned area when the regulatory decree is issued only, excluding, thus, internally displaced persons, refugees in asylum countries, and persons prosecuted for security reasons who are original residents in the area but were forced to abandon their properties due to political unrest and sometimes military hostilities.

It is important to note that the DPC annexed 50 sectors within these two areas for their interest and claimed ownership over them. Later, the Damascus governor transferred the ownership of these sectors, as state-owned shares, to the Damascus/Cham Holding, who established ownership over these shares in return for promises of granting the owners of annexed properties little compensation and alternative housing units.