The exceptional challenge posed by the COVID-19 pandemic must lead health authorities of all areas of Syria to coordinate their response to save lives, and external actors such as the World Health Organisation (WHO) and governments to implement realistic measures and start dealing with state and non-state actors alike.

As the world is tackling the spread of the COVID-19, Syria faces additional challenges. Nine years of conflict have created conditions of vulnerability all over the territory, while some populations such as Internally Displaced People (IDPs) living in camps or in houses where sanitation is not adequate, and detainees as well as abductees are even more fragile. Given the hardship to implement recommendations provided by the WHO to the public and states, it is essential legal and de facto authorities make every effort to protect the population without leaving anyone behind, and work together in order to tackle the spread of the pandemic at the national level.

1. Hardship to implement basic measures

As the epidemic spread, the WHO has been assisting states and the public to protect themselves and delivered messages. The institution thus published sets of recommendations.

| WHO recommendations to authorities and health care workers working in humanitarian contexts: |

| 1. Limit human-to-human transmission, including reducing secondary infections among close contacts and healthcare workers, preventing transmission amplification events, strengthening health facilities 2. Identify and provide optimised care for infected patients early 3. Communicate critical risk and information to all communities, and counter misinformation 4. Ensure protection remains central to the response and through multi-sectoral partnerships, the detection of protection challenges and monitoring of protection needs to provide response to identified protection risks 5. Minimize social and economic impact through multi-sectoral partnerships.[1] |

| WHO recommendations to the public: |

| 1. Wash your hands frequently 2. Maintain social distancing 3. Avoid touching eyes, nose and mouth 4. Practice respiratory hygiene 5. If you have fever, cough and difficulty breathing, seek medical care early 6. Stay informed and follow advice given by your healthcare provider.[2] |

The most critical measures requested in order to curb the progression of the pandemic consist in social distancing and frequent hand washing. These measures, as simple as seem, are virtually impossible to apply in the vast majority of contexts in Syria.

a). A divided country

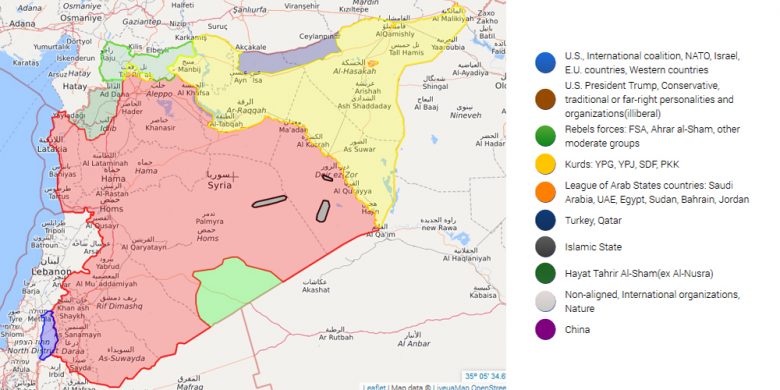

As a result of the conflict, Syria currently is under a variety of authorities, resulting in a divided country, where communications and coordination are kept to a bare minimum.

The Syrian government controls a vast part of the territory, from Aleppo city to Suweida, including the capital Damascus and Lattakia.

Northeast Syria is under the authority of several actors. While the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria controls a majority of the territory, Russia and the Syrian government are present in small areas. Operation Peace Spring, led by Turkey in October 2019, also resulted in the occupation by Turkey of the area between Ras al-Ayn and Tell Abyad.

In the northwest, the province of Idleb currently is under the authority of opposition armed groups and Hayat Tahrir al-Sham. The Idleb Health Directorate coordinates the health sector and works in collaboration with Turkey to prepare its response to the pandemic. The province of Afrin was subject to Turkey’s Operation Olive Branch in March 2018. Ever since, it has been occupied by Turkey, who is now responsible of the protection of its inhabitants. Euphrates Shield area, including Al Bab and Jarablus is also under control of Turkey, who is thus responsible for the protection of its inhabitants.

Current state of control over Syria. Credit: https://syria.liveuamap.com.

This fragmentation leads decisions to be taken at local levels and prevents a global management of the crisis to be implemented.

b). A dire economy forcing people to go to work

Devastated by 9 years of an expensive conflict, neither the Syrian state nor de facto authorities seem to be in capacity to provide Syrians with adequate social welfare subsidies. Other factors, such as fires affecting the wheat crops, Lebanon’s financial crisis initiated in August 2019 and the Caesar Act adopted by US Congress also added to an economy already significantly weak.[3] For Syrians, unable to count on the support of a Welfare state, and who have been hit by a hard economy and most of the time unable to build up saving for the past decade, it will be impossible to provide for the family while staying away from work for an extensive period of time, compromising the efficiency of any confinement measures undertaken by legal and de facto authorities.

c). Some specifically vulnerable populations

Among the Syrian population, two groups are especially vulnerable to a pandemic. Over the past nine years, the conflict has displaced civilians massively. In June 2019, UNOCHA recorded 6,1 million IDPs. More than a million of displaced people live in camps, where sanitary conditions are such that it is virtually impossible for the population living there to implement basic sanitary measures, including social distancing and hands washing.[4] IDPs who sought refuge at relatives’ or inadequate housing also face difficult sanitary conditions prone to the spread of the disease. Detainees and abductees represent another particularly vulnerable population. The practice of arbitrary arrests and detention has been widely reported by NGOs. The appalling sanitary conditions of detained puts them at high risk of contamination, with no hope of treatment on the part of the government.[5]

d). All over the country, a health system on its knees

Nine years of conflict have deeply ingrained fear and distrust among the population and legal and de facto authorities. This results in a lack of transparency on the part of authorities, wary of disclosing information pertaining to their health sectors, including the number of hospitals they can provide, and adds to the already concerning situation. Our understanding of the real capacities of government, Self Administration and Opposition health sectors are therefore summary, and relies heavily on a research led by the London School of Economics. [6]

In areas hold by opposition, heavy shelling campaigns by the Syrian government and Russia have destroyed numerous health infrastructures such as hospitals and medical centres. Idlib Health Directorate informed on 22 March 2020 that five patients were suspected of being infected by COVID-19. Since then, 900 tests reached a WHO partner in the area, and 5 000 additional tests will be sent over the coming week.[7] The authorities have implemented self-isolation measures such as closing mosques, schools and markets and instructed the population to self-isolate. However, in absence of financial assistance from the state, it is unlikely the population will be able to comply with these measures for an extensive period of time. In case of the spread of the epidemic, the health system of the area would rapidly be under pressure, as reports show there are currently in Northwest Syria only 166 doctors and 64 health facilities, “mostly operating with minimum-capacity infrastructure.”

In Northeast Syria, torn by Turkey’s Operation Peace Spring, the Self Administration announced on the 19th March the “closure of restaurants, cafes, malls, public places and small private clinics, with a mandatory curfew for all citizens except medical personnel, grocery store workers and food delivery truck drivers.” The region, accounting for over 4 million of the population, only has 11 hospitals.

In areas it controls, the government took measures including “the partial closure of borders, the suspension of the majority of unessential economic activities, the reduction of the public sector to 40% of its capacity through the introduction of a two-shift part-time system, and the closure of schools, universities, restaurants and other nonessential public facilities.” In these areas, systematic corruption, a dire economy and heavy sanctions imposed by the international community on Syria prevent a health system from being able to efficiently treat the population for a pandemic of the ongoing scale.

e). A dire need of funding and access

In these circumstances, it is essential for medical NGOs to be able to set up medical centres to be able to test the population, isolate patients tested positive with the virus, and treat them. This requires funding, and access, that is currently impeded for political and practical reasons.

A number of sanctions currently weigh on Syria. In December 2019, Russia and China vetoed the renewal of UN resolution 2165 adopted in 2014 that allowed cross-border aid delivery, forcing the UNSC to reduce by half the scope of the resolution, closing several crossings. Since 2011, numerous governments, including the US and the European Union, have also imposed sanctions on Syria, impacting all sectors, including that of health.

2. Obligations of states and non-states actors

As NGOs have repeatedly stated over the course of the past nine years, states and non-state actors must respect human rights.

a). Obligations of the Syrian Government

The right to health is an economic and social right recognized by the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), signed by Syria. Among other obligations, the Covenant mandates states to ensure health facilities, goods, and services, including the underlying determinants of health such as water available, accessible, acceptable, and of good quality.

Practically, the right to health commands the Syrian government to provide accurate information to its population. This includes ways of contamination, sanitary measures the population can take to protect itself, information related to the number of cases and available treatment. The government must also comply with the underlying obligation of non-discrimination, and ensure that patients are treated equally regardless of their ethnicity, religion and social class, entailing that corruption in the medical sector must be scrutinised and firmly banned.

b). Obligations of Turkey

Article 56 of the Fourth Geneva Convention provides that the Occupying Power has the duty of ensuring and maintaining, with the cooperation of national and local authorities, the medical and hospital establishments and services, public health and hygiene in the occupied territory, with particular reference to the adoption and application of the prophylactic and preventive measures necessary to combat the spread of contagious diseases and epidemics.

Article 14(1) of Protocol I also mandates the Occupying Power ‘to ensure that the medical needs of the civilian population in occupied territory continue to be satisfied’

In areas occupied by Turkey, including in Afrin province, Euphrates Shield area and Peace Spring area, Turkey must therefore ensure it takes every measure to protect the population. In order to comply with this obligation, it is essential for Turkey to acknowledge and coordinate the situation, first domestically, and then in Syrian areas under its control. Turkey must also comply with the ICESCR and ensure that health facilities, goods, and services, including the underlying determinants of health are available, accessible, acceptable, and of good quality. In areas under its control, Turkey must therefore apply the same principle of non-discrimination, and ensure the protection and treatment of the population regardless of ethnic, religious and political considerations. Similarly, practices Turkey has been carrying that impede the protection of the population, such as the interruption of water supply, must cease without delay.[8]

c). Obligations of Non-State Actors

Non-state actors such as NGOs, and de facto local authorities are similarly bound by human rights obligations, including the right to health, that they must make every effort to guarantee to civilians under their administration. This, similarly, requires the de facto authorities in opposition areas, such as Idleb’s Health Directorate and the Autonomous Administration’s Health Department, to be transparent about their real capacity and to provide the population and journalists with periodical update about the condition of their health system and the treatment of the patients. The authorities must also ensure that patients are treated equally regardless of their ethnicity, religion, gender and social class.

3. Dangers of exceptional measures for democracy

In most countries affected by the pandemic, strict exceptional measures have been taken by government in order to fight the spread of the virus. In this highly exceptional period, it is essential that government ensure these measures do not infringe citizens’ liberties and rights beyond what is strictly necessary. If and when exceptional measures, such as confinement, quarantine or curfews, were to be taken by legal or de facto authorities in Syria in order to curb the progression of the pandemics, it is of utmost importance to ensure that they are dictated only by the concern for the population and remain proportionate to the objective. Authorities must limit their decisions to these measures and to a limited period of time.

4. Conclusions

Countries heavily hit by the pandemic have accounted for thousands of deaths, while being able to rely on solid health systems, to mandate their population to confine and for them to oblige. In conditions such as Syria’s, the toll that might result of the spread of the virus could be abyssal.

As reactions from the US, who promptly closed their borders yet knows a striking increase of cases, showed, the spread of the epidemic knows no border or political inclination. In Syria and despite the war, people keep travelling, moving between areas hold by all legal and de facto authorities. The fight against the spread of the disease must therefore be organised on the national level and coordinated between all areas. It is essential that doctors all over Syria, regardless of the authority they rely on, cooperate and coordinate their action plan.

Recommendations

1). To the legal and de facto authorities

- Ensure that health facilities, goods, and services, including the underlying determinants of health such as drinkable water are available to the population without discrimination on the basis of ethnicity, religion, social class, gender.

- Ensure that health care workers from all regions coordinate their efforts to fight the spread of the epidemic regardless of political affiliations.

2). To donors

- Ensure that local NGOs and medical workers are trained for the management and treatment of COVID-19;

- Coordinate with de facto authorities and not solely the government in order to accelerate the dissemination of information, material and staff;

3). To the WHO

- Communicate with NGOs and de facto authorities and not only the government in order to accelerate the dissemination of information, material and staff;

4). To governments

- Implement an exceptional lifting of sanctions imposed to Syria that directly and indirectly affect the ability of the government and other parties to provide health support, in order to maintain a basic functioning of the health system, accompanied by a tight monitoring in order to ensure the funding are spent on the health sector and in a way compatible with the ICESCR;

- Reassess the legitimacy of sanctions affecting the health sector and civilian lives after the end of the pandemic;

- Implement a realistic response to the epidemic and start working with non-state actors, including de facto authorities in Northeast and Northwest Syria who implement health services.

5). To Syrian and International NGOs

- Provide factual information about all areas of Syria in order to evaluate the needs and the evolution of the sanitary crisis;

- Ensure that support provided by donors to tackle the crisis reaches all areas of Syria

6). To Syrian media

- Ensure an unbiased and transparent coverage of the epidemic in all areas with a focus on the people affected by it.

[1] Interim Guidance: Scaling-Up Covid-19 Outbreak Readiness and Response Operations in Humanitarian Situations, Including Camps and Camp-Like Settings, Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC), 17 March 2020, https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/system/files/2020-03/IASC%20Interim%20Guidance%20on%20COVID-19%20for%20Outbreak%20Readiness%20and%20Response%20Operations%20-%20Camps%20and%20Camp-like%20Settings.pdf.

[2] Basic protective measures against the new coronavirus, World Health Organisation, 18 March 2020,

https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public.

[3] Massive Wheat Crop Fires Threaten Syria’s Food Security, Syrians for Truth and Justice, 22 June 2019, https://stj-sy.org/en/massive-wheat-crop-fires-threaten-syrias-food-security/; Jihad Yazigi, Syria’s Growing Economic Woes: Lebanon’s Crisis, the Caesar Act and Now the Coronavirus, Arab Reform Initiative, 26 March 2020, https://www.arab-reform.net/publication/syrias-growing-economic-woes-lebanons-crisis-the-caesar-act-and-now-the-coronavirus/

[4] Humanitarian Update Syrian Arab Republic, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), 28 January 2020, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/FINAL%20VERSION%20HUMANITARIAN%20UPDATE%20NO.%208.pdf

[5] Syria’s Detainees Left Even More Vulnerable to Coronavirus, Human Rights Watch, 16 March 2020,

https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/03/16/syrias-detainees-left-even-more-vulnerable-coronavirus

[6] Gharibah, Mazen and Mehchy, Zaki, “COVID-19 pandemic: Syria’s response and healthcare capacity.” Policy Memo. Conflict Research Programme, London School of Economics and Political Science, London, UK 2020

http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/103841/1/CRP_covid_19_in_Syria_policy_memo_published.pdf

[7] Statement by the Regional Director Dr Ahmed Al-Mandhari on COVID-19 in the Eastern Mediterranean Region, World Health Organisation, 27 March 2020, http://www.emro.who.int/fr/media/actualites/regional-director-covid-19-statement.html

[8] Interruption to key water station in the northeast of Syria puts 460,000 people at risk as efforts ramp up to prevent the spread of Coronavirus disease, UNICEF, 23 March 2020, https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/interruption-key-water-station-northeast-syria-puts-460000-people-risk-efforts-ramp