Introduction

Language plays a very important role in human lives, as it creates identity and is a vital part of human connection, social integration, education, and development. However, many languages are at risk of extinction.[1] If languages become extinct, the cultural diversity in communities speaking them will decrease, fading as a result of the loss of traditions, memories, and unique patterns of thinking and expression associated with language and which are precious resources for a better future.[2] To draw the attention of the international community to the seriousness of language preservation, since 2000 the United Nations has designated 21 February of every year as International Mother Language Day — a day to both celebrate and remind the world of the importance of mother languages and the need to maintain them.

The reality of Syria’s diverse minorities and the different languages spoken within the country, which reflect Syria’s unique and rich multiculturalism, prompted us to prepare this report to address the importance of Syria’s mother languages. In this report, we will shed light on the international instruments guaranteeing those languages’ protection and reflect on how the Syrian government deals with the diverse languages of minorities in its territories. We will study the extent of the Syrian government’s interest in maintaining Syria’s mother languages and compare it to related international covenants and norms.

Additionally, we will cite the perspectives of Syrian opposition bodies and the actions they have taken regarding language in their areas of influence over the past few years. Finally, we will outline the solutions to maintaining Syria’s rich cultural mosaic, especially as it relates to language.

-

The mother tongue and the legal frame for recognizing it as a human right

We can define a mother language as a language spoken by particular people with unique features in terms of characters, vocabulary, grammar, sentence structure, and phonetics. A mother language can be written or passed down orally from generation to generation. Speakers of each language do not need to have a state of their own. Today, the number of globally recognized languages exceeds six thousand,[3] even as there are less than 200 countries in the world today. Besides, it is not necessary for a language to be confined to a specific geographical area. For example, the Arabic language is spoken in more than twenty countries, as is the case for English and French. The Spanish language is not only spoken in Spain, but in some European and Latin America countries. The Portuguese language is also spoken in several countries in Europe, South America (Brazil), Africa (Angola and Mozambique) and regions in Asia.

Since people use languages as a tool for communication and mutual understanding, depriving minorities from their right to use their ancestral language and forcing them to use another is both discriminatory and unacceptable. Doing so is incompatible with the principle of equality of rights and would likely lead to backlash from those affected because, as we discussed, a language is not only spoken words, but a form of identity and character which guarantees the preservation of their cultural heritage. Minorities across the world face great difficulties today in preserving their mother languages in both their public and private lives, especially those who are subjected to discrimination on an ethnic, religious and/or national basis.[4]

The international community became aware of the difficulty maintaining minority languages when it started setting rules framing human rights and regulating the relations of states between each other, as well as the relations of states with the peoples and minorities living within their territories. Article 26 of the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights obligated all signatory states to equalize all their citizens to ensure that they are effectively protected and not subject to discrimination on any basis, including by nation and language. The Covenant also affirms in Article 27 that minorities shall not be denied the right, in community with the other members of their group, to use their own language, considering language as one of the basic human rights.[5]

Several subsequent international documents – inspired by the aforementioned Article – emphasized and elaborated this issue, among them the Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities, issued by the United Nations General Assembly under Resolution No. 47/135 of 1992,[6] the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, adopted by United Nations General Assembly under Resolution 61/295 of 2007,[7] and the 1992 European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.

The number of the international conventions issued on this matter reflects the need for all states to commit to their duties towards the diverse languages of their peoples, especially as those conventions are inspired by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which is binding on countries that have ratified it, including Syria.

The commitment of states to what is stipulated in previous charters does not only mean that they should not practice repression against a certain minority, people, or component to prohibit them from using and developing their mother tongue, but that states shall also take adequate measures to create favorable conditions to enable persons belonging to minorities to express their characteristics and to develop their culture, language, religion, traditions, and customs.[8] Additionally, states should take measures in the field of education to encourage knowledge of the histories, traditions, languages, and cultures of the minorities existing within their territory. Thus, attempts by some states to eliminate minorities by forcibly integrating and melting them in another nation and language – mostly those of the ruling majority population – are unacceptable in the eyes of international law and would serve as flashpoints for outbreaks of violence and counter-violence.[9] In the following paragraph, we will cite policies and practices adopted by the Syrian successive governments in this regard, and the extent of their commitment to the aforementioned international charters and arrangements.

-

Deprivation of the use of mother tongue as a form of cultural genocide

The concept of genocide first emerged in the 1940s, in conjunction with the Second World War, by the Polish lawyer Rafael Lemkin. For Lemkin, genocide is not only, or even mainly, mass murder, since it based on ethnic, national, or religious considerations that distinguish it from other crimes against humanity and war crimes.[10] Lemkin also sees that cultural genocide, which is the systematic destruction of traditions, values, languages, and other elements that make one group of people distinct from another,[11] is one of the main forms of genocide.[12] Because of the importance of this concept and its representation in contemporary real events, such as the crimes of genocide against the Jews (the Holocaust), the temporary committee mandated by the United Nations to draft the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of 1948 had already included in its last draft the concept of cultural genocide, which contained the element of language cleansing, but it was then removed after a group of representatives of sixteen countries voted against that.[13]

Among those that refrained from legally recognizing the concept of cultural genocide were countries with colonial histories full of violations against indigenous peoples, such as Britain, the Netherlands, and Belgium, and others known for persecuting indigenous people or other peoples within their borders such as the United States of America, the Union of South Africa, Iran, and Turkey.[14]

What was striking during the discussions of the committee was that the Syrian government’s envoy at the time supported the idea of including the concept of “cultural genocide” as a form of genocide[15], in the Convention, stressing that the Syrian constitution guarantees respect for the cultural rights of minorities present on its territory and also guarantees their right to learn their mother tongue in schools.[16]

The constitution referred to here is of 1930, which became null in 1950, following the coup d’état of 14 December 1949, by Adib al-Shishakli which gave the power to Hashim al-Atassi. Then, a constitutional committee was formed consisting of thirty-three members led by Nazim al-Kudsi, and it indeed drafted a new constitution which was ratified on 5 September 1950.[17]

Unlike that of 1930, the 1950 constitution completely abandoned the constitutional rights of minorities to maintain their identity and their freedom to enjoy their right to learn their native language. The new constitution neither affirmed nor contained anything similar to the previous constitution’s Article 6, which stipulated that “Syrians are equal before the law and they are equal in enjoying civil and political rights and in their duties and assignments, with no discrimination between them in this because of religion, sect, origin or language.”[18]

The 1950 constitution instead provided in Article 1 that Syria is of Arab identity and the Syrian People are part of the Arab nation,[19] without paying any consideration to the other components of the Syrian people like the Kurds, Syriac Assyrians, and others. The constitution also provided in Article 4 that “the Arabic language is the official language in the state”. [20] The Kurdish language, for example, was completely excluded, in a practical implementation of Lemkin’s concept of cultural genocide. The 1950 constitution also indicated in its Article 3 “Islamic jurisprudence shall be the main source of legislation.”[21]

-

Policies of the Syrian governments towards the mother tongue of non-Arab components of society

Before delving into the policies enacted by successive Syrian governments, we will reflect on their legal framework and the actions that framework permits.

-

Legal frame

To determine whether a state fulfills its obligations towards the indigenous peoples and minorities in its territories, we should look to the laws of the country which are meant to stipulate the ability of minorities to exercise rights provided for in international charters and arrangements, including the right to speak, maintain, and develop their mother tongue. Constitutions in democratic states mostly provide for these human rights,[22] given that a country’s constitution is considered the father of all its laws, according to the principle of the hierarchy of laws. In order to determine the extent to which the Syrian state has fulfilled its obligations in this regard, we will look at the current Syrian constitution of 2012, which is a semi-reproduced version of its predecessor in 1973.

We note that the Syrian constitution did not mention the right of non-Arab components of the Syrian people to speak in their mother tongue, but rather stated in Article 4, which is copied from the previous constitution, “the Arabic language is the official language of the state”. This means that the Syrian Constitution failed to acknowledge the right of Syrian minorities to use their mother tongue or pass it on to their new generations through education. As such, the law creates inequality between the different components of the Syrian people, as the constitution favors the largest component of the Syrian people and ignores the others, contrary to what the constitution itself states in the third paragraph of Article 33: “Citizens have equal rights and duties”. How can citizens possess equal rights and duties when there is no right for the non-Arab components to learn in their mother tongue and they are denied the tools to maintain and develop their languages?

We find another example of discrimination in the Syrian Constitution’s preamble, where it writes that Syrians – with all their components and nationalities – are part of the Arab nation, and that the Syrian Arab Republic is proud of its Arab identity.

Since the aforementioned Syrian constitutions are inspired by the constitution of the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party, which stipulates in its eighth article that Arabic is the official language of the state and is recognized in the writing and the education of its citizens. It is worth mentioning that the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party has ruled Syria since 1963, and its eminency was guaranteed by Article 8 of the 1973 Constitution which stated that the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party was the leading party of society and state. Despite the exclusion of this Article from Syria’s most recent 2012 constitution, the party has enjoyed the same powers it has always enjoyed, and the Syrian People’s Assembly elections that took place in 2020 were the best witness to that.[23]

Article 9 of the 2012 Constitution guarantees “the protection of cultural diversity of the Syrian society with all its components and the multiplicity of its tributaries, as it is a national heritage that promotes national unity within the framework of the territorial integrity of the Syrian Arab Republic.” However, this language is nothing more than decorative text, because it is unacceptably broad and ambiguous. Despite its words, since its adoption, the Kurds in regime-held areas have not been allowed to teach their own language in government schools or to open schools specialized in teaching Kurdish. In the following paragraph we will address the practical application of the aforementioned constitutional articles.

-

The Practical application of the constitution articles

Successive Syrian governments, after the 8 March 1963 coup which led to the Ba’ath Party assuming power, took several actions against minorities’ languages in Syria, including marginalization, exclusion, eradication, and integration. For instance, over the past decades, Kurdish publications were banned. In 1987, the Minister of Culture expanded the scope of the ban to include audio-visual (video) tapes of Kurdish music and several decisions were issued prohibiting a Kurd from speaking the Kurdish language in official circles, as well as preventing them from listening to Kurdish songs at weddings and special events.[24]

According to some sources, the prohibition of teaching the Kurdish language in schools and universities was reaffirmed by a secret decree issued in 1989, and only few Kurdish materials were allowed to be published since then, including an Arabic-Kurdish dictionary in 2004.[25] However, in 2009, the Syrian authorities prevented the celebration of Newroz (the national day of the Kurds) in Kurdish areas, and thus arrested several Kurdish citizens for preparing for the festivities and brought them before the military judiciary.[26] Besides Newroz celebrators, the Syrian government has also arrested those who show interest in Kurdish culture, language, and art.[27]Moreover, editors of schools’ geography books since 1967 have omitted any mention of Kurds and officials at civil registries have pressured Kurds not to give their children Kurdish names.[28]However, in the period after Hafez al-Assad’s death in 2000 to the first years of his son Bashar al-Assad’s rule, the government became more lenient with the Kurds to satisfy them in part and prevent unrest and destabilization.[29]

We conclude that successive Syrian governments have not only denied Syrian minorities their identities and languages, but have deliberately tried in various illegal ways to integrate and dissolve those languages — especially the Kurdish language. It is worth mentioning that Syrian governments used less restrictive policies with other non-Arab minorities than those used against the Kurds. For example, Armenians and Assyrians were allowed to establish schools, clubs, and cultural societies in which to teach their languages.[30]

-

The policy pursued by the Syrian opposition regarding the mother tongue of the non-Arab components in Syria

In the first half of September 2016, the High Negotiations Committee (HNC) unveiled a plan to bring about a political transition in Syria and to end the five-year civil war in the country.[31] The plan consists of three main phases: six months of negotiations and a ceasefire, forming a transitional government with President Bashar al-Assad stepping down, drafting a new constitution, and holding elections supervised by the United Nations after 18 months of transitional rule. Although it was based on the commitment of the Geneva Declaration of 2012[32] to supposedly achieve equal opportunities and non-discrimination, the transitional plan’s formulation contradicts the establishment of this kind of inclusive society. More specifically, the first general principle of the HNC failed to appropriately confront Syria’s past imbalances and failed to lay the foundation for institutional reform:

“Syria is an integral part of the Arab World, and Arabic is the official language of the state and the Islamic culture represents a fertile source for intellectual production social relations between Syrians regardless of their ethnic affiliations and religious beliefs, as the majority of Syrians belong to Arabism and are religiously committed to Islam and its tolerant message that is characterized by moderation.”

HNC’ adoption of such a principle indicates its implied authoritarian policies, which embodies in a form described by Alexis de Tocqueville as the ‘tyranny of the majority’, in which obedience is enforced by constraint not by justice. Tocqueville proposed a distinctive human rights principle to refute tyranny in the name of the people by saying:

“A general law, which bears the name of justice, has been made and sanctioned, not only by a majority of this or that people, but by a majority of mankind. The rights of every people are therefore confined within the limits of what is just.”[33]

The HNC thereby gave a tyrannical status to the future Syria, which accordingly would give priority to specific religious and cultural groups over others. This not only undermines the creation of an inclusive, authentic society open to all forms of social identity, but also mimics the kind of discriminatory political environment created by President al-Assad.[34]

Since the Syrian opposition occupied, as Amnesty terms, the Kurdish-majority region of Afrin following Operation Olive Branch on 18 March 2018, local councils of the Ministry of Local Administration in the Syrian Interim Government – operating under the Syrian Opposition Coalition – replaced the Kurdish curricula of the preparatory and the following stages with curricula in which Turkish and Arabic are the most used. Furthermore, it gave Kurdish students classes in Kurdish in allotment hours, despite the fact that the Kurds constituted the overwhelming percentage of the population of the Afrin region before its occupation. The present curricula of the Interim Government is difficult for Kurdish students to understand, especially for those who do not speak Arabic.[35]

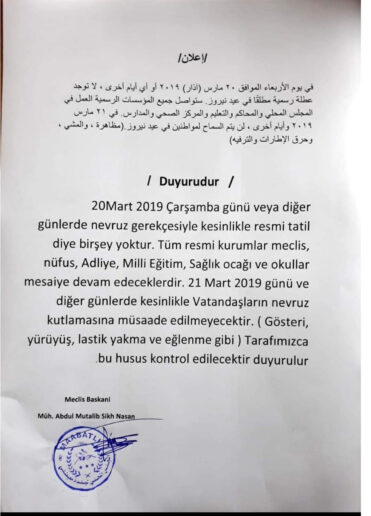

Furthermore, all statements, reports, and decisions issued by the institutions of the interim government in Occupation-controlled areas are issued in both Arabic and Turkish, without any regard for the indigenous Kurdish language. Traffic and institution signs were replaced by others written in Turkey and Arabic. Local councils issued driving licenses in Arabic and Turkish with the emblem of the Seljuk Empire (found by Tughril Bey. Seljuks are of the Turkish dynasty). The Turkish-established local councils in the area also issue orders prohibiting the celebration of Nowruz. One order, issued a mere day before Nowruz on 20 March 2019, by the local council of the town of Maabatli/Mabeta, prohibited celebrating Nowruz and was written in Arabic and Turkish.[36] All of these practices confirm the existence of a systematic policy to obliterate the Kurdish identity in this region in particular, and in Syria in general.

The Maabatli/Mabeta local council’s decision to prohibit the celebrations of Nowruz.

Credit: Rudaw Media Network and independent Syrian pages on social media.

-

Possible responses to maintain and develop mother languages in Syria

As we mentioned above, the diverse languages in Syria constitute a beautiful mosaic and are a vital part of our national cultural heritage, so we must maintain and improve them. Minorities have the right to be respected with their different characteristics and traditional cultures and to use, maintain, and develop their own languages. We have to abolish the exclusionary mentality of the Ba’ath Party, which sought to melt all Syrian languages into the Arabic pot. The issue of preserving and developing minorities’ languages is not a complex issue — relevant international charters and arrangements can guide the way and outline obligations for Syria to follow.

Accordingly, the coming Syrian government must avoid taking any action or behavior that would deprive indigenous peoples and minorities living in Syria from speaking their mother tongue. On the contrary, it must take measures and procedures to protect indigenous minorities’ cultural and linguistic identities, create the conditions for the promotion of these different linguistic identities, and ensure that children have adequate opportunities to learn their mother tongue. These duties should be provided for in the next constitution, in accordance with Article 27 of the International Covenant on the Civil and Political Rights of 1966, as well as Article 2 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities of 1992.

The coming government must also grant the right to indigenous peoples, such as the Kurds, Syriacs, Assyrians, Armenians and others, to revive, use, and develop their history, languages, oral traditions, philosophies, written systems, and literatures, and pass them on to future generations, as well as naming local communities, places, and people in their own language. This will require place-name restoration for the towns that have been Arabized by the successive Ba’ath and other Syrian governments. Governments must also grant indigenous peoples the right to establish and manage their educational systems and institutions and provide education in their own languages.

It is not sufficient to call for the right of peoples to revive their heritage, culture, and language. The state must help make those rights a practical reality, since they cannot be achieved by mere wishes. Communities will need material and technical support which the government, not individuals, has access to. Taking such measures by the coming government is consistent with what was stated in Articles 13 and 14 of the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

In addition, penal sanctions should be stipulated against anyone who commits acts that deprive indigenous peoples and minorities from enjoying their linguistic and cultural rights. Those actions aimed at melting and dissolving other nationalities and languages into a single national or linguistic pot should be considered criminal offenses. Furthermore, clear criteria should be established to distinguish between integration and assimilation, as the former is necessary to create a healthy society in which equality and pluralism prevail, while the latter undermines the collective identity of peoples living within the territory of the state. These legislative measures are supported by the commentary on the Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic or Religious and Linguistic Minorities, submitted by the Chair of the Working Group on Minorities of the Sub-Commission for the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights, Mr. Asbjorn Eide.

Taking the previous measures to preserve, develop, and protect the languages within the Syrian territory from extinction is consistent with the principle of equal citizenship. While the majority of the Syrian governments and opposition parties advocate for the principle of equal citizenship, few make plans or take serious steps to practically enact that principle. Instead, they use the term “equal citizenship” in local and international conferences and meetings only for media consumption and thereby receive support from the international community.

In this regard, in addition to the international documents mentioned in this paper, it is possible to benefit from the constitutions of countries that have undergone experiences similar to Syria’s. For example, the Iraqi constitution states in Article 4 that the Arabic and Kurdish languages are both the official languages in Iraq, and it guarantees the right of Iraqis to educate their children in their mother tongues, such as Turkmen, Syriac, and Armenian in government or private educational institutions in accordance with educational regulations. In another example, the South African constitution stipulates eleven official languages in the country and obligates the state to take practical and positive measures to improve the status of these languages and promote their use. The Spanish constitution states that the official Spanish language is Castilian, and the other Spanish languages are considered official within self-governing societies according to their regulations. On the other hand, the constitution of the Kingdom of Morocco considers the Amazigh language an official language alongside Arabic and provides for the creation of a National Council for Moroccan Languages and Culture, whose mission is to protect and develop the Arabic and Berber languages.

-

Conclusion and recommendations

After we became acquainted with the concept of mother languages, their importance, and the need to maintain and develop them — especially in Syria, which is characterized by the multiplicity of languages and cultures that make up its civilization — we believe that it is of the utmost importance to maintain that pluralism and develop it through robust measures. We must escape the Ba’ath Party’s mindset which forces Syrians, as well as all those living in what is called the ‘Arab world’, to be proud of using the Arabic language while it deprives minorities from exercising the cultural and linguistic rights that characterize their own identities.

In order not to let marginalization and the disrespect of mother languages destabilize Syria, we believe that the coming government, and the transitional governing body set out in UN Resolution 2254, must take measures necessary to maintaining the languages in Syria. They should:

- Constitutionally provide for the designation of other languages in Syria as official languages in addition to Arabic, at least in the areas where their speakers live, and oblige the government to take the necessary measures to achieve this.

- Refer to the responsibility of the state to provide the appropriate climate and the necessary support to maintain the existing languages in Syria, and to ensure the ability of minorities to teach their languages and help them maintain their culture.

- Criminalize the attempted integration of minorities’ languages and cultures into a single linguistic or national pot, and consider them as crimes of racial discrimination.

- Evaluate linguistic and cultural pluralism as a source of wealth and strength for the new Syria.

[1] According to UNESCO, linguistic diversity is increasingly threatened as languages die out. Data says that 40% of the world’s population does not have access to education in the language they speak or understand, despite tangible progress in the framework of multilingual education based on the mother tongue, on the International Mother Language Day, languages without borders, is this year’s theme for promoting peace and diversity, United Nations website, 21 February 2020, https://news.un.org/ar/story/2020/02/1049711 (last visited: 21 February 2021).

[2] “Safeguarding Linguistic Diversity”, the International Mother Language Day, UN, https://www.un.org/en/observances/mother-language-day , (last visited: 21 February 2021).

[3] Paragraph 18 of a report by the independent expert on minority issues, Rita Isaac, entitled “Promotion and protection of all civil, political, economic, social and cultural human rights, including the right to development”, the twenty-second session of the Human Rights Council dated 31 January 2012.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Syria ratified this covenant on 21 April 1969, see the status of ratification, https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/_layouts/15/TreatyBodyExternal/Treaty.aspx?CountryID=170&Lang=AR (last visited: 9 February 2021).

[6] Article 4 of the aforementioned declaration stipulates that ” States should take appropriate measures so that, wherever possible, persons belonging to minorities may have adequate opportunities to learn their mother tongue or to have instruction in their mother tongue.”

[7] Article 13 of the same declaration states: “Indigenous peoples have the right to revive, use and develop their history, languages, oral traditions, philosophies, written systems and literature and pass them on to future generations, and to name local communities, places and people in their language and preserve them.”

[8] Article 4 of the Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities of 1992.

[9] Paragraph 21 of the Commentary on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National and Ethnic or Religious and Linguistic Minorities, submitted by the Chair of the Working Group on Minorities of the Sub-Commission for the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights, Mr. Asbjörn Eide, as well as Article 8 of the UN Declaration on Rights Indigenous Peoples of 2007.

[10] R. Lemkin, ‘Axis Rule in Occupied Europe: Laws of Occupation, Analysis of Government, Proposals for Redress’, (1944), pp. 79–95.

[11] “Cultural genocide is the systematic destruction of traditions, values, language, and other elements that make one group of people distinct from another” – Elisa Novic, The concept of cultural genocide: an international law perspective, (Oxford University Press, 2016) <http://hdl.handle.net/1814/43864

[12] Leora Bilsky, Rachel Klagsbrun, The Return of Cultural Genocide?, European Journal of International Law, Volume 29, Issue 2, May 2018, Pages 373–396, https://doi.org/10.1093/ejil/chy025

[13] Official Records of 1st Part of the 3rd session the General Assembly, 6th Committee, Legal questions, summary record of meetings )21 Sept.-10 Dec. 1948) p. 206 <https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/604635?ln=en>

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid., p. 200.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Majid Khadduri, ‘Constitutional Development in Syria: With Emphasis on the Constitution of 1950’, Middle East Journal, vol. 5, no. 2 (1951), pp. 137–160. JSTOR www.jstor.org/stable/4322268

[18] The Syrian Constitution of 1930, Article 6.

[19] The Syrian Constitution of 1950, Article 1. “Constitution of the Republic of Syria: Preamble.” Middle East Journal 7, no. 4 (1953), p. 521 http://www.jstor.org/stable/4322546

[20] Article 4, Ibid.

[21] Article 3, Ibid.

[22] For example, the “Swiss Confederation” constitution of 1999, which was amended in 2014 stipulating in its fourth article that the national languages are German, French, Italian and Romansh, as well as the Belgian Constitution issued in 1831 and its amendments until 2012, which stipulated that Belgium consists of four linguistic regions: the Dutch-speaking region , The French-speaking region, the bilingual region of the capital and the German-speaking region.

[23] Denounced as theatrical and fabricated.. the Ba’ath Party swap the legislative elections in Syria, Al Jazeera Net, 22 July 2020, https://www.aljazeera.net/news/2020/7/22/%D9%88%D8%B5%D9%81%D8%AA-%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%B3%D8%B1%D8%AD%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D9%88%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D9%81%D8%A8%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A9-%D8%AD%D8%B2%D8%A8-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A8%D8%B9%D8%AB (last visited: 9 February 2021).

[24] For example, the decision of the Governor of al-Hasakah No. 1012 of 1986, which prohibited speaking the Kurdish language in the workplace, and Resolution No. 1865, which affirmed the previous decision and also prohibited singing in non-Arabic at weddings and holidays.

[25] Syria: Kurds in the Syrian Arab Republic One Year After the March 2004 Events, Amnesty International, 24 February 2005.

[26] “The annual report on the human rights situation in Syria for the year 2009″, the Kurdish Organization for the Defense of Human Rights and Public Freedoms in Syria (DAD).

[27] “The ninth annual report on the human rights situation in Syria for the year 2009”, the Syrian Human Rights Committee, 15 February 2021, https://www.shrc.org/?p=9564 (last visited: 9 February 2021).

[28] “Group Denial: Repression of Kurdish Political and Cultural Rights in Syria”, HRW, 26 November 2009, https://www.hrw.org/report/2009/11/26/group-denial/repression-kurdish-political-and-cultural-rights-syria (last visited: 9 February 2021).

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] The Syrian opposition announces a political transition plan to end the conflict, BBC Arabic, 7 September 2016, https://www.bbc.com/arabic/middleeast/2016/09/160907_syria_opposition_proposals (last visited: 10 February 2021).

[32] “The most prominent points of the Geneva meeting plan on Syria”, Al Jazeera Net, https://www.aljazeera.net/news/reportsandinterviews/2012/7/1/%D8%A3%D8%A8%D8%B1%D8%B2-%D9%86%D9%82%D8%A7%D8%B7-%D8%AE%D8%B7%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D8%AC%D8%AA%D9%85%D8%A7%D8%B9-%D8%AC%D9%86%D9%8A%D9%81-%D8%AD%D9%88%D9%84-%D8%B3%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%A7 (Last visited: 10 February 2021).

[33] Alexis de Tocqueville: “Democracy in America” translated by Amin Morsi Qandil, part one and two. Books World Publications, first edition, Cairo, the print date is not visible. P 228.

[34] “Inclusivity framework vital to achieving transitional justice in Syria”, Syria Justice and Accountability Center, 5 October 2016, https://syriaaccountability.org/updates/2016/09/20/inclusivity-framework-vital-to-achieving-transitional-justice-in-syria/ (last visited: 10 February 2021).

[35] Education in Afrin is at stake .. Kurdish students face additional challenges, Enab Baladi Newspaper, 11 October 2020, https://www.enabbaladi.net/archives/422180 (last visited: 10 February 2021).

[36] “Syrian armed groups and local councils prevent the celebration of Nowruz in Afrin, Rudaw Media Network, 19 March 2019, https://www.rudaw.net/arabic/kurdistan/190320199 (last visited: 10 February 2021).