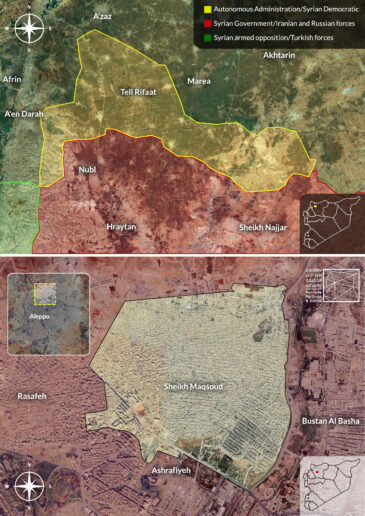

Correction: This report was amended on 12 April 2024. The number of primary checkpoints surrounding the Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafieh neighbourhoods is three, not four, as an earlier version said. The fourth, called Bani Zaid, is secondary.

Also, an updated map is included, as the previous version demarcated parts of the territories controlled by the Syrian government forces as falling within the scope of the AANES north of Aleppo.

The Syrian government forces have been keeping Kurdish-majority areas in the northern Aleppo province under a partial siege since September 2023.

The blockade is affecting communities in Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafieh neighbourhoods north of Aleppo city, as well as Tell Rifaat city and over 50 towns and villages in the al-Shahbaa region. These areas are run by civil entities affiliated with the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES).

Local sources interviewed by Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) said the military checkpoints of the Syrian government, primarily the Fourth Division—which encircle these areas and separate them from government-held regions—are obstructing the residents’ access to various essential supplies and imposing royalties on their entry. These supplies include food, medicines, and fuel allocations the area receives from the AANES.

The same sources stressed that due to royalties, which vary from checkpoint to checkpoint, the prices of some goods in the besieged areas have become twice those in government-held regions. The price inflation has exacerbated the financial woes of the predominantly Kurdish residents—especially the dozens of thousands of internally displaced persons (IDPs) who sought refuge in the al-Shahbaa area in the aftermath of Operation Olive Branch, which Türkiye launched into the Afrin region in northwest Syria in 2018. Notably, both the local and IDP communities are bearing the brunt of the blockade as they continue to struggle with abject financial and living conditions in the shadow of the ongoing conflict, as well as almost non-existent services, including healthcare, and international humanitarian relief.

The hampered and royalty-bound entry of vital supplies is but another instant of the intermittent blockades, of varying severity, that the government forces have begun to impose on the area since 2020. In 2022, the government forces tightened their control over the area’s entrances, banning all incoming supplies, including flour. Amnesty International described the stringent restrictions as a “brutal blockade” and called on the Syrian government to address the “dire humanitarian crisis.” The organization also stressed that “[t]his crisis is not only a moral imperative but also a legal one. The Syrian government has an obligation under international law to ensure its population has access to adequate food, medicine, and other essential supplies. By blocking such access, they are violating their rights.”

In this brief report, STJ sheds light on the crisis that continues to beset the local and IDP communities, who are battling with restricted entry of essential supplies. The report builds on four interviews STJ’s field researchers conducted with residents from the affected areas. All four civilian sources requested anonymity, fearing reprisals, considering that the areas’ residents have to cross military checkpoints to get medical services in Syrian government areas that are not available in their neighbourhoods.

The government checkpoint’s control over fuel entries had the most substantial impact on the lives of residents throughout the besieged areas. According to the sources, residents heavily rely on power generators and have thus been experiencing major power outages due to fuel scarcity.

Limited fuel supplies also adversely affected school activities and already scarce healthcare services in the al-Shahbaa area. In November 2023, schools and other educational centers suspended classes as fuel shortages paralyzed transport. In the same month, the Avrin Hospital, the only facility providing free services in the area, stopped 80 percent of its activities after it remained without fuel for a week.

Notably, the partial blockade coincided with unlawful Turkish airstrikes on energy infrastructure in northeast Syria. This restricted fuel allocations from reaching the cut-off neighbourhoods. In a statement to ANHA news agency, Deputy Head of the AANES-affiliated General Council of Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafieh Neighbourhoods, Arin Hanan, said that under these circumstances, the council managed to distribute “only 100 liters of fuel to each family” in November 2023.

Checkpoints Are Profiteering from the Blockade

Checkpoints Are Profiteering from the Blockade

Since 2019, a Kurdish civilian administration has been in charge of the Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafieh neighbourhoods located north of Aleppo city. The administration provides residents’ needs within a system of governance distinct from the Syrian government in the rest of Aleppo’s areas. The two neighbourhoods are home to nearly 22,000 families—approximately 80,000 individuals.

Notably, three primary checkpoints surround the Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafieh neighbourhoods. These are the al-Jazeera Carwash checkpoint, near the Armenian cemetery, on the Midya Weddings Hall Road; the Ashrafieh checkpoint near the Grand Mosque of Salah al-Din; and the Sikat al-Qittar (Railroad, also known as al-Awared) checkpoint on the Bustan al-Basha road. There is a fourth, but secondary, checkpoint, known as the Bani Zaid barrier, which is located near the al-Lairamoun roundabout. These checkpoints are operated jointly by the Fourth Division and the State Security Service (The General Intelligence Directorate).

Hisham Hajji,[1] a furniture carpenter in Sheikh Maqsoud Gharbi, said that these checkpoints “tighten their grip and restrict fuel supplies” every time there is friction between them and the AANES-affiliated administration in the neighbourhood. He added, “I only received 150 liters of fuel this past winter. Many residents had similar limited access to fuel. This also happened [in 2022].”

The checkpoints’ restrictions on fuel supplies rendered the two neighbourhoods’ informal electricity subscription system dysfunctional. The neighbourhoods mainly depend on fuel-powered generators, locally called amperes, owned by the residents or the neighbourhoods’ municipalities. This exacerbated the community’s financial burdens, especially as locals struggled with the Syrian government’s long-hour electricity rationing. Hisham said:

“[Owners] operated the generators five hours a week in return for 2000 SYP per ampere. That was an adequate price since the administration [in Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafieh neighbourhoods] provided the fuel. However, the measures imposed by the checkpoints caused the generators’ operation hours to drop from five to two hours. Then, owners managed to operate generators for three hours but raised the subscription fee to 3,500 SYP per ampere. Lately, the generators have been operating for four hours only in return for 4000 SYP per ampere.”

The informal electricity network’s subscription fee inflated as a direct consequence of the hike in the prices of unsubsidized fuel usually supplied by the AANES. Hisham said fuel was sold for 8,000 SYP per liter on the market before the siege. He added that with the start of restrictions by the checkpoints, fuel prices on the market “jumped to nearly 14,000 SYP per liter for the dark fuel [provided by the AANES] and 15,000 SYP per liter of the cleaner fuel [provided by the Syrian government].”

The consequences of the hampered fuel entries were not confined to price increases. Heating fuel shortages forced households to abide by harsh self-imposed rationing measures in the winter. These measures left the residents—including Hassan Barho’s wife and son—who had severe health issues,[2] especially helpless against the cold.

Hassan heads a family of five and escaped the Afrin region in 2018 to Sheikh Maksoud Garbi, where he works at a car parts store. Like Hisham, Hassan received only 150 liters of fuel in 2023, which failed to meet the needs of his wife, who has back and joint aches, and his son, who has quadriplegia. Due to their conditions, they both have to remain warm. Speaking about his son’s bed during the winter, Hassan narrated:

“Due to the lack of fuel and our tight finances, my son had epileptic seizures and needed treatment throughout the winter. We were forced to ration fuel and only turn on the heater briefly when my sick son woke up to warm the room a little. We had to ensure this small amount [of fuel] would suffice us for the longest time possible.”

According to Hisham, the Syrian government checkpoints are also restricting the entry of food and medicine, which boosted their prices by 80 to 100 percent compared to their prices in government-controlled areas. He said:

“The al-Jazeera Carwash checkpoint—the only checkpoint allowing supplies into the area—is imposing royalties on every item entering the two neighbourhoods. Therefore, if a parsley bunch is sold for 1000 SYP in the part of Ashrafieh held by the government, it is sold for 2000 SYP in the part of the neighbourhood controlled by the AANES.”

Hisham added that royalties imposed differ from checkpoint to checkpoint, stressing that the Fourth Division demands the largest sums of money:

“The merchants I dealt with told me that members of the State Security Service are asking for small sums of 2000 to 3000 SYP. However, the members of the Fourth Division accept only lucrative sums, which they demand based on the size of the industrial materials entering the neighbourhood. The Fourth Division, of course, is the highest authority at the checkpoint.”

In tandem with imposing royalties on essential supplies, the Syrian government checkpoints allow residents in Sheikh Maksoud and Ashrafieh to carry only limited amounts of cash upon seeking government-held areas. The warranted amounts hardly cover their needs. Elaborating on this, Hisham said:

“The checkpoints prevent civilians from carrying more than 500,000 SYP when leaving the neighbourhood. Until recently, the amount was 200,000 SYP [. . .]. This is presenting residents with challenges, especially when traveling to Aleppo for doctor appointments or treatment at State-run hospitals.”

The Blockade is Also Suffocating al-Shahbaa

The living conditions are equally abject in the al-Shahbaa region, home to over 91,000 people, among them 10,221 IDPS. The IDPs forced to flee the Afrin region during the 2018 Turkish incursion live in five camps across the area: 1,032 families in the Serdem Camp, 784 families in Berkhoudan Camp, 164 families in the Odeh Camp, 122 families in the Afrin Camp, and 109 families in the al-Shahabaa Camp, in addition to countless families who sought shelter in houses destroyed by the conflict.

Sharing the plight of locals in Sheikh Maksoud and Ashrafieh, residents in the al-Shahbaa are also grappling with royalties on the entry of fuel and other essential supplies, which is causing commodity prices to spike.

Shaker Mahmoud,[3] a taxi driver displaced from Afrin who now resides in Tell Rifaat city, said that the prices in the al-Shahbaa are 35 to 50 percent higher than those in the Aleppo regions controlled by the Syrian government. He added that the major challenge, however, is the limits the checkpoints have imposed on cash amounts that residents can carry upon leaving the area:

“The hardest thing is that we have to hide cash somewhere in the car while navigating the regime checkpoints headed to Aleppo from the al-Shahbaa. I had to do that when I took my injured wife to Sheikh Maqsoud for treatment. The government checkpoints allow [residents] to carry only 500,000 SYP. They permitted this amount only recently, for it used to be 200,000 SYP.”

Residents across the al-Shahbaa area are also struggling due to dwindling fuel allocations. Under the blockade, the family’s annual share of subsidized fuel fell from 400 to 200 liters. This left patients in the region prey to cold, as many cannot afford to buy unsubsidized fuel. One of these patients is Shaker’s wife, who underwent surgery for her broken kneecap and had to be kept warm all the time. Shaker narrated:

“We had to turn on the heater [. . .]. I bought six liters of fuel for 260,000 SYP. We kept the heater on for two to three hours in the morning and two to three hours in the evening. It is beyond our financial resources to consume larger amounts of fuel. I bought [180 liters] while my wife was injured. I am like every other IDP in the area, who have no means of support, are deplorably badly off and cannot afford healthcare if they fell ill and would end up dependent on others to even use the restroom.”

A’ziz Jamal,[4] an internally displaced fuel merchant based in Tell Rifaat, said the blockade also caused several commodities to disappear, such as residential gas cylinders. He added that the cylinder’s price rose to 350,000 SYP and that he had to “smuggle” cylinders from government-held areas as they remained unavailable on the market.

Jamal stressed that the status of IDPs in the al-Shahbaa is tragic, adding that the area would be on the verge of a “humanitarian crisis” if it were not for the few free clinics and humanitarian organizations that are helping the “poverty-stricken” community.

Notably, the enormous suffering of the al-Shahbaa residents was recently aggravated by water cuts, including drinking water. In February 2023, UNICEF allegedly stopped supplying water to the five IDP camps in the al-Shahbaa after it gradually interrupted its water services in the villages and towns across the area starting in 2021. Lack of water in the camps threatens to increase the spread of diseases, especially as the al-Shahbaa has already been struggling with low rainfalls, diminishing groundwater, and contaminated surface water.

[1] The source chose to use a pseudonym during an online interview on 22 February 2024.

[2] The source chose to use a pseudonym during an online interview on 8 March 2024.

[3] The source chose to use a pseudonym during an online interview on 9 March 2024.

[4] The source chose to use a pseudonym during an online interview on 10 March 2024.

Checkpoints Are Profiteering from the Blockade

Checkpoints Are Profiteering from the Blockade