In March 2018, Turkey and the opposition’s Syrian National Army (SNA) launched Operation “Olive Branch” into Syria’s Afrin region.

Large-scale human rights violations and displacement were recorded over the course of the military operation. While these were the direct consequences of the incursion, several less direct threats loomed large over the region, including breaches of property rights and critical changes in the demographic fabric.

During and after combat, SNA-affiliated armed groups called on internally displaced persons (IDPs) from across Syria to relocate to northwestern Syria. The armed groups induced the resettlement of thousands of IDPs in the region. The resettlements were greenlighted and assisted by the Turkish military and several humanitarian organizations. The IDPs came mainly from the northern countryside of Homs and Eastern Ghouta, in Damascus’s countryside.

Both IDPs and a large number of the families of SNA fighters were housed in the homes of Kurdish locals, who were forced to flee during the hostilities, or were coerced to abandon their houses by the factions that later controlled the region. Owners were threatened with arrest and told that they would be held liable should they refuse to leave their houses.

The civilian houses were used for resettlements after SNA-affiliated factions took control over the Afrin region and perpetrated large-scale and systemic property seizures, calling these properties “spoils of war”.

The seizures were only one dimension of the violations perpetrated against owners’ rights. The factions repurposed civilian structures and often turned them into investments. The locals’ houses were leased to IDPs.

Monitoring these practices, Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) has issued extensive reports corroborating that several faction commanders turned seized properties into high-profit investments. In a June 2022 report, STJ revealed that Muhammad al-Jasim (Abu Amsha), commander of the Suleiman Shah Brigade (also known as al-Amshat), was making millions of dollars out of local properties.

In addition to profiteering, STJ documented secondary seizures, whereby factions are expropriating several of the properties already seized in the aftermath of the 2018 offensive.

One of these factions is the Northern Hawks Brigade, which is affiliated with the Hayat Thaeroon for Liberation, operating in Kamrouk village, in Maabatli/Mabeta district, under the command of Hasan Hajj Ali, nicknamed Hasan al-Kheiriyah.

In early September 2022, the brigade forced 25 displaced families, originally from al-Rastan, in Homs’ northern countryside, to leave the houses they were assigned to upon arriving in the region. These houses originally belonged to Kurdish locals who were themselves displaced.

The testimonies STJ obtained for the purposes of this report demonstrate that the targeted families are denouncing the eviction orders because the faction intends to house its fighters and their families in them.

Notably, there are over 100 displaced families in Kamrouk village, who sought safety in the area from various parts of Syria, including the 25 families from Homs’ northern countryside. Additionally, there is a small segment of the original population, consisting of the elderly who remained in the area to protect their property, or families that returned after being displaced during hostilities.

Initial Seizures

To obtain details about the resettlement dynamics, STJ reached out to several IDPs from al-Rastan, who reside in houses originally belonging to Kurdish locals in Kamrouk village.

The sources stressed that they were admitted into these houses in May 2018, less than two months after the Turkish military and the SNA-affiliated factions took control of Afrin. They added that they were granted access to these houses by the Turkish military and the Sultan Murad Division, which was among the first armed opposition groups to establish a presence in the village.

Later, the IDPs obtained approval to remain in these houses from the Northern Hawks Brigade. The brigade took control over the village following a dispute with the Sultan Murad Division.

In early September 2022, a Kamrouk-based civilian IDP from al-Rastan provided STJ with an exclusive account of resettlement and housing conditions. He narrated:

“After we left al-Rastan, we were relocated to Afrin city. In the city, people told us that there is a depopulated village where we could live. Indeed, we went to the village. There were Turkish soldiers and fighters from the Sultan Murad Division. We told them that we were IDPs and had no place to stay. The Turkish soldiers allowed us to stay in the village’s houses. They searched the houses and dismantled some mines and explosives before they let us in.”

The source confirmed that members of the Turkish intelligence, demining teams, and interpreters accompanied the soldiers. The interpreters communicated with IDPs and verbally relayed to them the approvals to stay in the village’s houses. Later, several humanitarian organizations provided aid to a number of families. Commenting on the methods of relocation, the source said:

“All IDPs from Homs’ northern countryside were first assembled in Idlib city and brought onboard green buses. Immediately after that, several humanitarian organizations brought in large buses and encouraged people to move to Afrin. When we arrived in Afrin, fighters started to urge people to settle in the areas where their factions operated. Some IDPs chose certain villages and areas because they had relatives who were IDPs, who settled there earlier.”

In a second exclusive interview, the source narrated that the factions housed several displaced families from al-Rastan and other areas in seized homes and forced them to pay rents. He added that the residents had to pay 4,000 to 15,000 Syrian pounds in monthly rent to whatever faction controlled the area. The house rents gradually increased, reaching an average of 50 USD monthly.

Secondary Seizures are Common Practice

Even though the factions that initially controlled the Afrin region “presented displaced families with houses almost for free”— because the rents were quite minimal—the factions in control today continue to exploit the needs of IDPs.

In addition to forced evacuations or exorbitant rents, the IDPs struggle due to the factions’ recurrent clashes over financial resources.

Since 2018, Kamrouk village has been at the heart of the military front run mainly by the Northern Hawks Brigade, alongside the other factions stationed there. The brigade became the key player in the village after it signed an agreement with the Sultan Murad Division that led to the division’s withdrawal from the village. The brigade signed the deal to maintain a monopoly over the village’s financial resources.

Following the agreement, the armed groups operating under the Brigade made it a common practice to demand civilians to leave the houses where they lived, intending to house fighters and their families instead.

The evictions would happen every time the brigade’s active groups or their command in the village changed.

In an exclusive account, a third witness narrated:

“In 2019, after the Sultan Murad Division left the village, the Northern Hawks Brigade became our curse. The brigade unrelentingly tried to force us to leave the houses. It also threatened us into choosing between joining its ranks and surrendering our light weapons. We suffered lots of troubles, until Anwar al-Hassan, a Major within the Sultan Murad Division, intervened and resolved the conflict in the favor of civilians.”

The source added:

“Since August 2022, the Brigade has been undergoing several command changes. Several commanders have been substituted and relocated. The reshuffling followed the death of one of the brigade’s commanders in the area, Hassan al-Juma’a, and nicknamed al-Fardouneh. At the end of August, the village was put in the charge of two officials, sheikh Abu Abdulrahman Anjara and security officer Abu Ahmad Amniyeh. Nearly a week after they were assigned, they started asking us to leave the houses at gunpoint or threatening us with arrest, advocating that the brigade’s fighters and their families are more entitled to housing.”

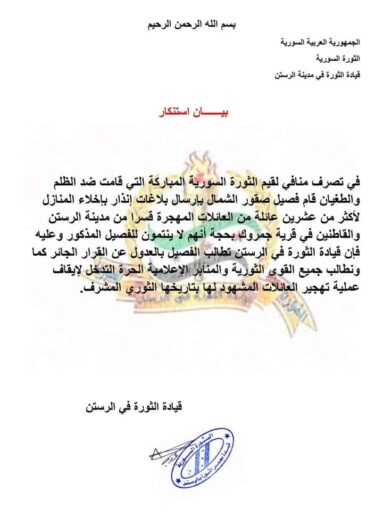

The families refused to leave the houses and issued a statement three days after the evacuation order, condemning the practices of the brigade (see appendix 2).

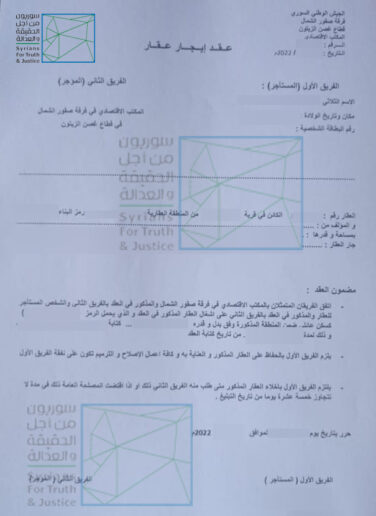

In response, the brigade resorted to fraud and attempted to trick the IDPs into signing surveys of relief supplies and household and utility contents, which are in reality rent contracts (see appendix 3). Several families signed the documents. However, the trick was later revealed and the remaining families refused to sign the contracts. In retaliation, the brigade threatened them with arrest in case they did not comply.

For a comment on the manipulation, STJ reached out to a member of one of the affected families. The source recounted:

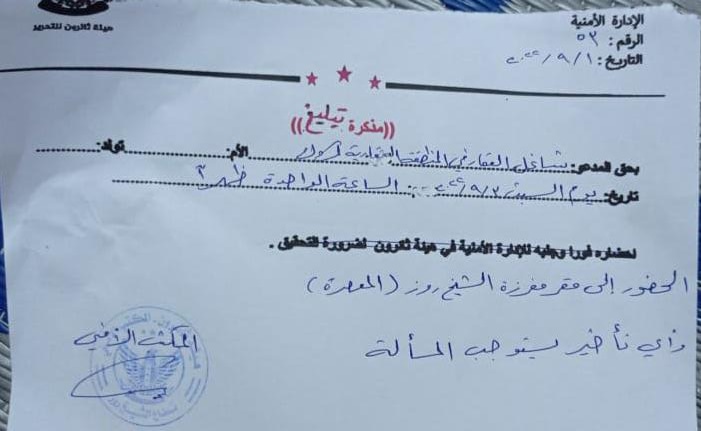

“After we refused to sign the rental contracts, the brigade threatened to arrest or sue us. On 1 September, the Brigade sent us an eviction notice and ordered us to show up at their headquarters, known as Sijin al-Ma’sara (al-Ma’sara Prison) at 1:00 P.M. on 3 September. They were trying to lure us into their post, which is far from the village to arrest us without having anyone around to protest. However, when the situation escalated among the people, and dignitaries and several commanders from the village and other areas intervened, the matter was resolved. A decision was made to maintain the status quo and the brigade withdrew the eviction orders temporarily.”

Appendix List

A warrant issued by the Security Administration of the Hayat Thaeroon for Liberation, under which the Northern Hawks Brigade operates, sent to a property occupant in Kamrouk village, in the Afrin region.

Statement made by families displaced from al-Rastan, in Homs’ northern countryside, condemning the notices they received from the Northern Hawks Brigades for refusing to join its ranks.

Exclusive photo obtained by STJ of the contract that the Security Office of the Northern Hawks Brigade forced some families to sign.