1. Introduction:

In countries with diverse demographic makeups, debates on the rights of ethnic, religious, and linguistic minorities preoccupy a vast space of discussions about political and cultural life, as well as the future of individuals and communities.[1] Moreover, in such countries, the relationship between the State and these minorities is often complex and contingent on the role assigned to language and religion in the State in general and further on the way the national identity and culture have been historically defined. Language and religion are core elements of the national identity. Therefore, the efforts aimed at the construction of a national identity monochromatically based on a single ethnicity, language, or religion continue to result in deficient protection of the rights of minorities—the others. In addition to this disadvantaged status, minority groups might share a history of conflict with each other, as is the case in Syria.

In countries undergoing critical societal and political shifts, such as those that have survived civil conflicts or disputes, the relationship between the State and minorities represents a massive challenge. Parties to the conflict tend to assert the strong affiliation between the State on the one hand and the religion, culture, and language of the majority—the nationalist, religious, or denominational majority—on the other hand. This challenge is paramount in the case of Syria, where sweeping protests broke out in 2011 and later spiraled into a bloody armed conflict between the forces of the Syrian government and the opposition. Minorities, ethnic, linguistic, cultural, and religious, engaged in the conflict in various ways and were often rendered fuel and victims of hostilities.

In Syria, one of the most crucial preliminary steps for the political process to succeed is openness to negotiation among stakeholders. These include ethnic, religious, and linguistic minorities and all parties wishing to partake in developing Syria’s future constitution and playing a role in its political life.

Furthermore, the integration of Syrian minorities to help them have access to equal citizenship—pertaining to rights and duties—mainly requires the reformation of the State’s legislative and administrative doctrines. Such reform must be geared towards the recognition of the existence of minority groups and also of the country’s diversity. This recognition enables members of these groups to represent themselves as individuals and groups within the government and effectively participate in political life. Notably, the sought reforms can be realized through an embrace of the provisions of international conventions and treaties already ratified by Syria and those to be endorsed in the future, as well as amendments to the Syrian Constitution and legislation, while ensuring the participation of these minorities in the committees charged with preparing and drafting the constitution, representative institutions, and other consultative structures.

The application of a proportional representation system by the local administrative councils is one way to ensure minorities are reflected in executive decisions and represented in central and local governments. This system facilitates the redistribution of political power and helps to emphasize the national, religious, or cultural distinctiveness of these minorities as a primary component/s in Syria.[2]

Notably, this paper was developed around the topics discussed during a workshop organized by Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ). The workshop was held under STJ’s program, “Bridging the Gap between Syrians and the Constitutional Committee,” the activities of which have culminated in the release of several similar papers. The previous publications focused on transitional justice as a guarantee to achieving sustainable peace; gender-sensitive transitional justice as an essential requirement to support the transitional path; social justice and how its principles have degraded into merely theoretical texts in Syria; and the modes of effective involvement in political life.

In the workshop grounding this paper, STJ offered training on the rights of minorities and indigenous peoples in Syria and also the means for ensuring the fair representation of all the Syrian components in political negotiations and constitutional processes. Researchers, and activists working in northeastern Syria attended the workshop, along with legal professionals and minority rights experts.

The definitions of minorities and indigenous peoples, as stated in international conventions and instruments, and demonstrations of how to involve minorities in the constitution-writing process were among the topics covered during the workshop. The attendees addressed the state of minorities and relevant international obligations through the lens of human rights. Within these conceptual frames, they analyzed the status of minorities in Syria, their position in the Syrian constitution, how its texts approach minorities, and, thus, the treatment of minority issues it calls forth.

In addition to the inputs from the workshop, this paper draws from several research papers and reports on the rights of minorities in Syria and worldwide.

2. Syria as a Pluralistic and Diversity-Rich Country

Syria is a dwelling place for a plethora of religious and ethnic groups.[3] These groups have a wealth of languages and ties to multiple geographies. Ethnically, Arabs, the majority group, live alongside Kurdish, Armenian, Assyrian, Circassian, and Turkmen communities.

In terms of faith, Syria is also home to Muslims (Shia, Sunni, Alawi, and Druze), Christians, and Yazidi populations. Additionally, the country’s many cultural elements and socio-economic levels, which go well beyond religion and ethnicity, give its variety several more layers.

The modern territorial State of Syria was established by the French Mandate assigned in the aftermath of the First World War and the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire. The sovereign independent State, which replaced the French Mandate in 1946, was founded on the old colonial territorial arrangements provided for in the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 that were subsequently approved by the League of Nations in 1924.

The Syrian State was formed through these political and administrative arrangements, processes, and practices, which were reflected in the local social and cultural structures and later determined the composition of the ruling elites in the new State. In other words, the Sykes-Picot Agreement constituted the historic framework for the new sovereign authority in Syria. However, the agreement failed to dictate its identity. This authority lacked the legal, political, and cultural conditions necessary for building an identity.

In his book Syria: Revolution from Above, Raymond A Hinnebusch argues that the “Syrian state was, from its very birth, seen by most Syrians as an artificial creation of imperialism, undeserving of affective loyalty. In this vacuum, one attempt was made by the Syrian Social Nationalist Party to foster a ‘Pan-Syrian’ territorial identity distinct from Arabism, and some other political actors either fell back on sub-state identities or a wider universalistic ideology, such as Islam or communism. But, the dominant identity that would fill the vacuum would be Arabism and the most successful political elites and movements would be those which saw Syrian identity as Arab and Syria as part of a wider Arab nation.”[4]

Since independence was followed by the predominance of Arab nationalism, the Arab nationalist elite played an active role in establishing the unyielding association between the hegemonic ethnicity/majority and sovereign authority. The Arab identity of the State—which has been consistently affirmed in the official and semi-official discourse,[5] supported by the sovereign violence of the State’s military and security organs—has been the most prominent form of discrimination against the other components of Syria.[6]

3. The Syrian Constitution and Laws Marginalize Indigenous Groups

-

The Role of the Syrian Constitution

The origins of the current regime are rooted in the 1963 coup d’état by the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party, spearheaded by Hafez al-Assad, and the emergence of the then Arab nationalist tide. The regime also derives founding principles from the 1973 Constitution. This constitution established the power structure and state of affairs that followed the coup and made it the status quo.

The existing Syrian Constitution provides theoretical protection for several fundamental rights to which Syrian citizens, including those belonging to minority groups, are entitled.[7] These rights include participation in political life, freedom of expression, and freedom of association. In Article 34, the Constitution provides that “[e]very citizen shall have the right to participate in the political, economic, social and cultural life and the law shall regulate this.” In its Article 42(2), the Constitution also establishes that “[e]very citizen shall have the right to freely and openly express his views whether in writing or orally or by all other means of expression.”

A similar stance is maintained in Article 44, in which the Constitution guarantees that “[c]itizens shall have the right to assemble, peacefully demonstrate and to strike from work within the framework of the Constitution principles, and the law shall regulate the exercise of these rights.”

Further reference to the rights of minority groups and protected cultural rights in Syria exists in Articles 9 and 33. In Article 9, the Constitution guarantees that “[a]s a national heritage that promotes national unity in the framework of territorial integrity of the Syrian Arab Republic, the Constitution shall guarantee the protection of cultural diversity of the Syrian society with all its components and the multiplicity of its tributaries.” In Article 33(3), the Constitution stipulates that “[c]itizens shall be equal in rights and duties without discrimination among them on grounds of sex, origin, language, religion or creed.”

However, these articles continue to constitute a theoretical frame that is both overbroad and ambiguous. Since these articles were inscribed into the Constitution, the Syrian State did not recognize the diverse components existing in Syria, nor did it officially acknowledge their distinct historical, cultural, or geographical identities. None of the minorities in Syria are blatantly mentioned in the body of the Constitution, and the Syrian government took no steps to implement any of these articles.

At odds with these articles, the marginalization of ethnic minorities, including Kurds, Armenians, and Assyrians, in Syria continues, accompanied by several discriminatory practices that impair their rights. This is not to mention that the Constitution includes other texts that breach the dictates of the articles cited above. An exclusionary language overrides the Preamble, which reads: “The Syrian Arab Republic is proud of its Arab identity and the fact that its people are an integral part of the Arab nation. The Syrian Arab Republic embodies this belonging in its national and pan-Arab project and the work to support Arab cooperation in order to promote integration and achieve the unity of the Arab nation.” The Preamble does not only obliterate the distinct character of the other components in Syria or bring them all under the mantle of the Arab nationality. It also draws a distorted picture of Syria’s ethnic constitution. The words Arab and Arabic recur over 10 times in the Preamble alone. This bias creates the erroneous impression that the Syrian people is composed of the Arab component only. While this impression does not reflect the reality in Syria, it also estranges the rest of the components and gives rise to an atmosphere of negativity.

This exclusionary language persists in Article 3 of the Constitution. The article stipulates that “Islamic jurisprudence shall be a major source of legislation,” depriving the other religious groups in Syria of taking an active part in regulating public life. The same article provides that “[t]he religion of the President of the Republic is Islam.” The limitations this article projects on other religious groups are contrary to the equality bestowed on all Syrian citizens by Article 33 of the Constitution.

The same othering linguistic trend overrides Article 4 of the Constitution. The article states that “[t]he official language of the state is Arabic.” In return, the Constitution does not include any texts that openly recognize the right of other Syrian components to use their mother languages. Furthermore, the Constitution does not even establish these components’ right to teach their languages to younger generations. This gap warrants a state of inequality among the constituents of the Syrian people and condones favoritism towards the majority group in various respects, including linguistic rights. Article 4 is thus in stark contrast to Article 33(3), which establishes that “[c]itizens shall be equal in rights and duties.” This discrepancy begs the following question—how can citizens be equal while non-Arab groups are denied the right to speak or teach their mother languages and are deprived of tools to preserve and promote them?[8]

Additionally, Article 8(4) of the Constitution stipulates that “[c]arrying out any political activity or forming any political parties or groupings on the basis of religious, sectarian, tribal, regional, class-based, professional, or on discrimination based on gender, origin, race or color may not be undertaken.” Notably, given the nature of Syria’s demographic fabric, the discrimination and exclusion practiced against several components for decades, and the failure of existing parties, especially those that echo the rhetoric of the Ba’ath Party, to protect minorities in their political literature, it stands as only natural for parties and political clusters to emerge that concern themselves with advocating the causes of certain groups and communities that have demands that are religious and nationalist to a certain extent. However, Article 8 robs these groups and communities of an essential political tool that would have otherwise helped them protect their interests.

-

The Role of Syrian Laws

The gaps and inconsistencies in the Constitution are also rife in the remaining Syrian legal frameworks, including the Multi-Party Law. In Article 5(d), the law prohibits the formation of “a party based on religion, tribe, region, class, occupation, or on discrimination on grounds of race, sex, or color.”[9]

This paragraph raises several issues. First, it falls within the scope of the above-discussed Article 8 of the Constitution. Second, it counters the formation of parties on national, religious, or other grounds. The distinction the article attempts to make is ambiguous, as it does not clearly indicate whether the ban is on the formation of ethnicity- or religion-centered parties or those that advocate for the causes of religious or ethnic minorities. Therefore, the article has to be clarified so as not to be interpreted as being against the formation of nationalist parties.

Against its own dictates, the Multi-Party Law exempts parties affiliated with the Progressive National Front from licensing and considers them authorized by default. Additionally, Article 22 of the General Elections Law No. 5 of 2014 allocated the Ba’ath Party—purely Arabist—at least 50 percent of the 250 seats at the People’s Assembly, with party members admitted into the Assembly as representatives of workers and farmers.

Since Syria is a multi-nationalist, multi-ethnic, and multi-religious country, it is only reasonable for religious or ethnic parties or groups to emerge to advance the causes of the groups they represent and who have been marginalized and discriminated against on a nationalist, religious, or ethnic basis for decades. However, in its present form, the Multi-Party Law denies these groups, including the Yazidi community, appropriate representation. This is even though Yazidis exist in Syria as a religious community that has its own distinct doctrine and thus has the right to have an entity to represent its views and aspirations.

4. Some of the Syrian State’s Discriminatory Practices against Minorities

In their governance mechanisms, successive Syrian governments have relied on preferential treatment. This has undermined the affected groups’ access to equal citizenship and caused a proliferation of religious, sectarian, and ethnic divisions. The policies and legislation in force discriminate between citizens on the one hand and impose religious and sectarian alignments on them on the other. For instance, religious personal status frameworks vary according to the religious affiliation of citizens, leading to the application of different laws as well as differentiation between Muslims and non-Muslims on one side and between men and women on the other.[10]

Notably, the Syrian government did grant a few Syrian components access to a limited set of rights. However, this access lasted for limited periods, and the rights were at risk of being revoked whenever the authorities wished. These rights were always bound by several considerations. For instance, the government allowed some parochial schools to teach Syriac. This authorization, nevertheless, was based on the disciples’ right to speak the language of the church but not their right as members of a linguistic minority.

These parochial schools were licensed by Legislative Decree No. 55 of 2004 on the regulation of private and private-public education in Syria. The decree contains numerous articles and paragraphs that keep the parochial Syriac schools under threat of total closure. Article 57 states that these “[educational] institutions may not be part of a political or religious institution or association.” This article alone gives the Syrian authorities the power to shut down these schools if they so desire.[11]

Unlike the Assyrian community, which had constrained linguistic liberty, the Yazidi community had no rights whatsoever, constantly struggling with the woes of discrimination practiced by successive Syrian governments. Yazidis were denied performing their religious rituals, learning or passing down the teachings of their religion, building new places of worship, or renovating older ones like other Syrian religious groups and sects. Worse yet, Yazidis were coerced to attend Islamic education classes at schools and were subjected to Islamic Sharia-based personal status laws.[12]

Similar prohibitions shackled the linguistic rights of the Kurdish community. Kurds were banned from speaking, learning, or teaching Kurdish. Additionally, releasing publications in Kurdish was outlawed, while the names of many villages in Kurdish-majority areas were Arabized.

In a pretense attempt at fostering linguistic diversity in Syria, geared toward insulating itself from criticism, the Syrian government dedicated limited class hours to a few local languages at the language institutes affiliated with the universities of Damascus and Aleppo. However, the government still refrained from recognizing the taught languages as official or authentic. Article 9 of the bylaws of the Higher Language Institute at Damascus University lists only foreign languages upon referring to the institute’s departments, with none assigned to local languages.[13] In the official sphere, the government embraced local languages only once. This happened when the Syrian Ministry of Information allowed the broadcasting of bulletins in Kurdish, along with Arabic, Syriac, and Assyrian, through Sanabel Radio, launched in al-Hasakah city on 1 February 2015. Nevertheless, these steps were only symbolic gestures and implied no obligation on the part of the State. The government still did not take measures or pass legislation to offer minorities the opportunity to learn their languages at State-run institutes.

In addition to the domestic laws’ failure to oblige the State to protect minority rights, the Syrian educational system played a primary role in further widening the rifts within Syrian society. The adopted system neglected to a large extent the necessity of introducing the religions existing in Syria to students or even familiarizing Syrians from various religious and denominational backgrounds with each other.

5. The Syrian Opposition Equally Fails to Respect Diversity

The March 2011 uprising created a space for all Syrian components to express their visions and voice their demands through direct engagement in the protests or contributions to documents and statements addressing Syria’s future.

Additionally, entities across the opposition’s spectrum attempted to utilize representation management tools in their approach to all Syrian communities and social components and conveyed a sense of reassurance at the level of texts they adopted. Nevertheless, with the call for a political transition, the opposition failed to dispel the fears and concerns of minority groups. It was even a few steps behind the Syrian government in its handling of minority affairs. This was evident in both the High Negotiations Committee’s (HNC) 2016 transition plan and in how it approached Syria’s diversity.[14] The plan’s first principle states: “Syria is an integral part of the Arab World, and Arabic is the official language of the state and the Islamic culture represents a fertile source for intellectual production social relations between Syrians regardless of their ethnic affiliations and religious beliefs, as the majority of Syrians belong to Arabism and are religiously committed to Islam and its tolerant message that is characterized by moderation.”

With this rhetoric, the plan left the other components outside Syria’s boundaries and deprived them of the chance to take part in shaping the State in favor of a single group. Additionally, the plan prioritized certain religious and cultural groups at the disadvantage of others. This not only undermines the potential for the emergence of an inclusive and genuine society that is open to all configurations of societal identity but also reproduces the discriminatory political climate the al-Ba’ath Party has been cultivating for a long time.

In 2021, the Syrian Opposition Coalition (SOC) sought to renew its discourse on the management of Syrian diversity. It issued the Syrian Revolution’s Charter of Human Rights and Public Freedoms. Nonetheless, the Charter stood as a rigid document, echoing the language Syrians have constantly struggled with in successive Syrian constitutions. The Charter establishes rights to work, mobility, citizenship, equality, education, protest, and participation in public life. Furthermore, the Charter safeguards the rights to freedom of intellect and creed, among other rights and fundamental liberties, backed by international covenants and instruments, as well as Syrian constitutions.

Nevertheless, the Charter does not inscribe mechanisms that guarantee access to these rights and freedoms, address the rights of religious, ethnic, and linguistic minorities in Syria, or provide the means to safeguard their rights as groups entitled to rights that preserve their singular characteristics. The Charter is almost a replica of existing domestic legal frameworks. Item 11 of the paragraph on the right to education barely diverges from Articles 3 and 9 of the enforced Syrian Constitution, both of which stress the State’s respect for all religions and the necessity to protect the cultural diversity of the Syrian society with all its components and the multiplicity of its tributaries.

Therefore, the opposition’s efforts to manage diversity remain a matter of upholding formalities because they used an overly generalized discourse that offers little to no assurance to a large number of Syrians who have endured the effects of texts tied to the discriminatory practices of the ruling power for decades. Furthermore, the opposition’s discourse failed to overcome the shortcomings of the mainstream culture, at the heart of which lies the national identity, as it did not encourage the formation of a public mindset that is aware of, believes in, and embraces diversity.

Notably, the Syrian opposition’s failure to come up with an open discourse that advocates tolerance toward the other is reflected in the practices of affiliated armed groups in northern Syria, where they maintain effective control supported by the Turkish State.

In these areas, local authorities continue to promote Arabic and Turkish at the disadvantage of Kurdish—the language of the ingenious community—in a deliberate form of marginalization.[15] There is also a blatant denial of the rights of the Yazidi community. The operative armed groups have repeatedly banned Yazidis from performing their rites and intentionally destroyed their shrines or desecrated their burial places.[16]

Similar restrictions hamper minority rights in the areas held by the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS-former al-Nusra Front). The HTS banned Christians from ringing church bells or displaying crosses. It also seized church facilities and monasteries and transformed them into military centers.[17] Equally grave violations by the HTS are suffered by the Druze communities under its control.[18]

6. Muted Diversity at the Constitutional Committee

The barring of minorities and consequent disregard for Syrian diversity were not limited to texts adopted by several opposition entities. A similar lack of minority sensitivity is evident in structures established to realize a political transition in Syria. One of these structures is the Syrian Constitutional Committee (SCC).

The SCC was created under UN decision No. 2254 and was officially declared after the National Dialogue Conference, held in Sochi, Russia, in 2018. The SCC emerged under a Russian-Turkish-Iranian consensus as part of an international strategy to resolve the Syrian conflict. Structurally, the SCC has a Large and a Small Body. The Large Body has three sub-groups of 150 men and women, 50 representing and nominated by the Syrian government, the Higher Negotiations Committee, and civil society. The Small Body comprises 45 men and women, 15 nominated by the government from among its 50, 15 nominated by the Syrian Negotiations Committee from among its 50, and 15 from among the 50 representatives of civil society.[19]

The formation of the SCC was subject to vast debates and objections to the candidates and the components represented by the guarantor parties. The SCC became a space onto which were projected international interests, with hardly any regard to the efficacy or knowledge of candidates in the Syrian context or the country’s demographic or socio-cultural makeup.

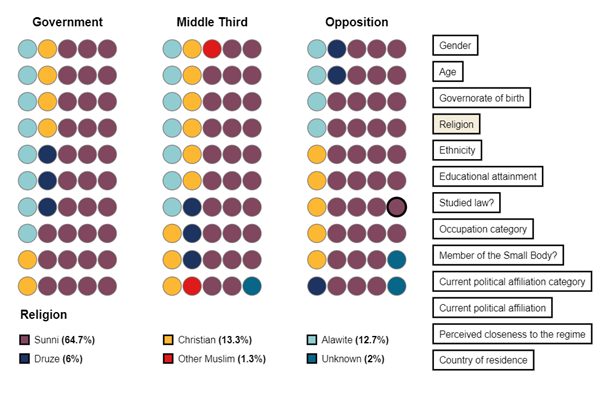

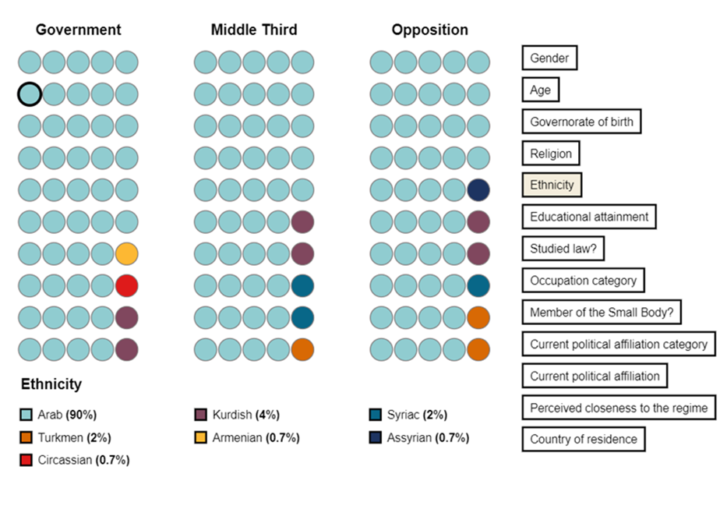

Notably, the SCC is remarkably balanced in terms of its religious and denominational components. It even “marginally over-represents Christians and Alawite Muslims at the expense of Sunni Muslims, according to national statistics presented in the World Factbook” (See infographic 1).[20] However, the balance is disrupted at the ethnic level, with the representation of all ethnic minorities combined amounting to only 10 percent. The representation scale critically tilted when it came to Kurds, making only 4 percent, which is less than half of their percentage of the Syrian population. Additionally, several Kurdish political components were entirely left out of the Committee (See infographic 2).

Infographic 1-Religious representation within the SCC (source).

Infographic 2-Ethnic representation within the SCC (source).

7. Recommendations

Drafting constitutions for countries rendered fragile by conflicts does not only seek to restructure their political institutions. More so, the process aims at the recognition of these countries’ historical and/or ethnic singularities and also to openly express the political, cultural, and symbolic distinctive facets of their sub-national entities.

Furthermore, participation in constitutional processes remains one of the democratic State’s central mechanisms to protect the interests of minorities through political operations initiated with the majority’s consent. This objective is the essence of the process of drafting a constitution. Therefore, over the course of drafting, it is necessary to represent all citizens, whether as political blocks or parties, and fairly consider their demographic distribution and cultural and religious orientations. Regarding the drafting of the future Syrian constitution and minority representation, participants in the STJ workshop recommended that:

- The future Syrian government must refrain from any conduct that would deprive minorities and indigenous peoples in Syria of their right to speak their mother languages. Instead, the government must preserve and promote these groups’ languages; take needed measures and actions to protect their cultural and linguistic identities; create the conditions for the promotion of those different linguistic identities; and ensure that members of these groups have adequate opportunities to learn and be schooled using their mother tongues. The government can achieve this by inscribing these steps as State duties into the future constitution and by undertaking to provide these groups with the resources needed to obtain those rights, in conformity with Article 27 of the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights as well as with Article 2 of the 1992 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious, and Linguistic Minorities.

- The future Syrian government must grant indigenous peoples and minorities, such as Kurds, Syriacs, Armenians, and others, the right to revitalize, use, and develop their history, languages, oral traditions, philosophies, writing systems, and literature, and transfer these down to their future generations. Additionally, the government must grant them the right to give communities, places, and persons culturally relevant names and mainstream the original names of the areas and towns that have been Arabized by the successive Ba’athist and other Syrian governments. Within this sphere, these groups must be given the right to establish and manage their educational institutions and systems and provide education in their languages. The government must adopt effective measures to fulfil these obligations. It is not sufficient for the government to provide for the right of these peoples to revitalize their heritage, culture, and language. The government must assist in doing so in practice since this requires not only the desire to empower these groups but also the material and technical support that States, not individuals, usually possess. Furthermore, measures set up to this end must be consistent with Articles 13 and 14 of the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

- The future Syrian government must stipulate penalties against individuals or groups who commit acts that result in the deprivation of indigenous peoples and minorities of their linguistic and cultural rights and ensure that such acts—aimed at the fusion and assimilation of diverse nationalities and languages into a single national or linguistic melting pot—are considered criminal offenses. Therefore, the government must establish clear and detailed criteria to differentiate between acceptable integration, marginalization, assimilation, and eradication to guarantee that integration does not become assimilation or undermine the collective identity of persons living in the territory of the State. Notably, integration is different from assimilation, since integration develops a common space marked with equal treatment and standing before the law, which also warrants pluralism. Such legislative measures are established in the commentary on the Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities, submitted by the Chairman of the Working Group on Minorities of the Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights.

- The future Syrian government must take the above-listed measures to preserve, protect, and develop the diverse languages in Syria under the principle of equal citizenship, advocated by the majority of Syrian governments and opposition, without any steps or plans to implement textually insinuated protections.

- The future Syrian government must particularly ensure that members of religious groups and denominations enjoy the right to religious freedom; respect for their cultural specificity; are not subjected to religious education or personal status laws that are unaligned with their beliefs; and are treated on an equal basis before the law, the courts, and within the framework of the Constitution. The government must also address other social practices and trends, including holidays, through which these groups have been discriminated against.

Within the context of constitutional processes and the integration of minorities, several constitutions were drafted in similar conditions as those Syria is experiencing. These include the Iraqi constitution,[21] which in Article 4 states that “the Arabic language and the Kurdish language are the two official languages of Iraq. The right of Iraqis to educate their children in their mother tongue, such as Turkmen, Syriac, and Armenian shall be guaranteed in government educational institutions in accordance with educational guidelines, or in any other language in private educational institutions.” For its part, Article 2 states that “[t]his Constitution guarantees the Islamic identity of the majority of the Iraqi people and guarantees the full religious rights to freedom of religious belief and practice of all individuals such as Christians, Yazidis, and Mandean Sabeans.”

Another constitution that Syria can build from is that of South Africa, which recognizes 11 languages as official, obliging the State to “take practical and positive measures to elevate the status and advance the use of these languages.” This is a progressive approach to linguistic freedoms, for the Constitution did not only grant minorities and indigenous peoples the right to speak their mother languages but also provided an obligatory frame that advocates for the promotion of these languages.

There is also the Spanish constitution, which states that the official Spanish language is Castilian, while considering the other languages official within self-governing societies according to their regulations. Furthermore, there is the constitution of the Kingdom of Morocco, which considers the Amazigh language an official alongside Arabic and provides for the creation of a National Council for Moroccan Languages and Culture, whose mission is to protect and develop the Arabic and Berber languages.[22]

[1] While the concept of “minorities” is a persistent challenge because it still lacks a consensus definition at the international level, STJ will apply to the Syrian context the concept promoted by the United Nations Special Rapporteur on minority issues in the report he presented to the UN General Assembly in October 2019. That is: “An ethnic, religious, or linguistic minority is any group of persons which constitutes less than half of the population in the entire territory of a State whose members share common characteristics of culture, religion or language, or a combination of any of these. A person can freely belong to an ethnic, religious, or linguistic minority without any requirement of citizenship, residence, official recognition, or any other status.”

For additional information, see: “Syria: A Brief Guide to Protecting the Rights of Religious Minorities”, STJ, 29 November 2022 (1 November 2023). https://stj-sy.org/en/syria-a-brief-guide-to-protecting-the-rights-of-religious-minorities/

[2] Electoral Systems: Proportional Representation. https://moodle.univ-ouargla.dz/course/info.php?id=526&lang=en

[3] Minorities and indigenous peoples in Syria, Minority Rights Group: https://minorityrights.org/country/syria/

[4] Hinnebusch, R. (2002). Syria: Revolution from Above. RoutledgeCurzon. P. 18.

[5] In 1961, the country was officially named the Syrian Arab Republic.

[6] For histories of the formation and development of the Syrian State since the end of WW1 see: Van Dam, N. (2011). The struggle for power in Syria: Politics and Society under Asad and the Ba’th Party. I. B. Tauris; Hinnebusch, R. A. (2023). Authoritarian Power and State Formation in Ba`thist Syria: Army, Party, and Peasant. Routledge; Maʻoz, M., Ginat, J., & Winckler, O. (1999). Modern Syria: From Ottoman Rule to Pivotal Role in the Middle East; Ziser, E. (2001). Asad’s legacy: Syria in Transition. C. HURST & CO. PUBLISHERS; Wedeen, L. (2015). Ambiguities of domination: Politics, Rhetoric, and Symbols in Contemporary Syria. University of Chicago Press; George, A. (2003). Syria: Neither Bread Nor Freedom. Zed Books.

[7] The 2012 Syrian Constitution: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/91436/106031/F-931434246/constitution2.pdf

[8] “Killing Mother Tongues as a form of the Continued Cultural Genocide in Syria”, STJ, 22 February 2021 (last visited: 6 November 2023). https://stj-sy.org/en/killing-mother-tongues-as-a-form-of-the-continued-cultural-genocide/

[9] Legislative Decree No. 100 of 2011, Multi-Party Law (in Arabic), Syrian People’s Assembly website: http://parliament.gov.sy/arabic/index.php?node=55105&cat=4399&

[10] “Syria: Gender-Sensitive Transitional Justice is an Essential Requirement to Support the Transitional Path”, STJ, 19 June 2023 (Last visited: 15 November 2023). https://stj-sy.org/en/syria-gender-sensitive-transitional-justice-is-an-essential-requirement-to-support-the-transitional-path/

[11] Yousef, S. “Syria’s Assyrians during the Reign of President Bashar al-Assad” (in Arabic), Elaph, 7 September 2010 (Last visited: 16 November 2023). https://elaph.com/Web/opinion/2010/9/593591.html

[12] “Yazidis in Syria: Decades of Denial of Existence and Discrimination”, STJ, 5 September 2022 (Last visited: 16 November 2023). https://stj-sy.org/en/yazidis-in-syria-decades-of-denial-of-existence-and-discrimination/

[13] Bylaws of the Higher Language Institute at Damascus University (in Arabic): https://www.damascusuniversity.edu.sy/arabicD/?lang=1&set=3&id=324

[14] Operational framework for the Syria political process in accordance with the Geneva Communique (2012), the High Negotiations Committee of the Syrian Revolution and Opposition Forces, September 2016.

[15] Dershoy, H. “The Kurdish language between the government and the Syrian opposition after 2011” (in Arabic), ASO Studies, 7 July 2023. https://asostudies.com/ar/node/343

[16] “Yazidis in Syria: Decades of Denial of Existence and Discrimination”, STJ, 5 September 2022 (Last visited: 18 November 2023). https://stj-sy.org/en/yazidis-in-syria-decades-of-denial-of-existence-and-discrimination/

[17] “Idlib’s Christians Disenfranchised Until Their Church Bells Ring Again”, STJ, 26 December 2022 (Last visited: 18 November 2023). https://stj-sy.org/en/idlibs-christians-disenfranchised-until-their-church-bells-ring-again/

[18] “Idlib’s Druze Complain of Persecution”, STJ, 24 November 2022 (Last visited: 18 November 2023). https://stj-sy.org/en/idlibs-druze-complain-of-persecution/

[19] Constitutional Committee, Office of the Special Envoy of the Secretary-General for Syria: https://specialenvoysyria.unmissions.org/constitutional-committee-0

[20] Shaar, K. and Dasouki, A. “Syria’s Constitutional Committee: The Devil in the Detail”, 12 December 2023.

https://ar.karamshaar.com/syrias-constitutional-committee

[21] “The Constitutional Process in Syria: How Can We Draw on the Iraqi Experience?”, STJ, 25 October 2023 (Last visited: 19 November 2023). https://stj-sy.org/en/the-constitutional-process-in-syria-how-can-we-draw-on-the-iraqi-experience/

[22] “Killing Mother Tongues as a form of the Continued Cultural Genocide in Syria”, STJ, 22 February 2021 (last visited: 19 November 2023). https://stj-sy.org/en/killing-mother-tongues-as-a-form-of-the-continued-cultural-genocide/