-

Background

Twice in last March, Arab residents displaced from Shuyukh al-Fawqani district of Ayn al-Arab/Kobanî city in Aleppo, appealed to the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) to allow them to return to their homes they fled since 2015. This comes as the Syrian Democratic Forces’ Manbij Military Council (MMC) has allowed Kurdish people to return to neighboring villages. These appeals were just a new attempt to demand the right of return; the residents have earlier organized protests for the same demand; they were met with the authorities’ rejection on grounds of security imperatives.

In September 2014, when the Islamic State (IS) entered Shuyukh al-Fawqani, the village’s population was displaced in mass and never returned since then despite the IS’ withdrawal under fire from the international coalition and the SDF in 2015.

Testimonies obtained by Syrian for Truth and Justice (STJ) for the purpose of this report confirmed that dominant armed forces in Manbij denied displaced Arab residents a return and even visits to their villages, except in some exceptional cases. According to witnesses, military powers also used civilian houses in Arab villages for military purposes and continued to occupy them after the end of military operations in the area. The same powers allow Kurdish IDPs to return to their neighboring villages, as said by witnesses.

On 10 March 2023, hundreds of IDPs from the Shuyukh villages held a meeting to find a solution for their return issue, in the presence of tribal leaders/sheikhs and members of Manbij’s Clan Leaders’ Council – acts as a coordinator between the city’s tribes and democratic civil administration. Sheikhs and Council members pledged to work hard toward the return of IDPs in a short time, against a promise from locals not to attempt to access their villages without coordination with the SDF to avoid confrontations.

One of the attendees made a statement on behalf of the displaced population of the Shuyukh villages, in which he called the AANES to allow them to return to their villages. The statement recalled the repeated return requests the IDPs submitted to local authorities, for which they receive only promises. In addition, the statement denied the claims that their villages were military zones, citing cases of strangers taking over agricultural lands belonging to Arab original inhabitants – during their displacement – stressing that those strangers were civilians and did not belong to any political party.

| Syrians for Truth and Justice sent a copy of the report to the Manbij Military Council in early May 2023, requesting clarifications about preventing families from returning to their villages and areas. However, we have received none up to the report’s publication date. |

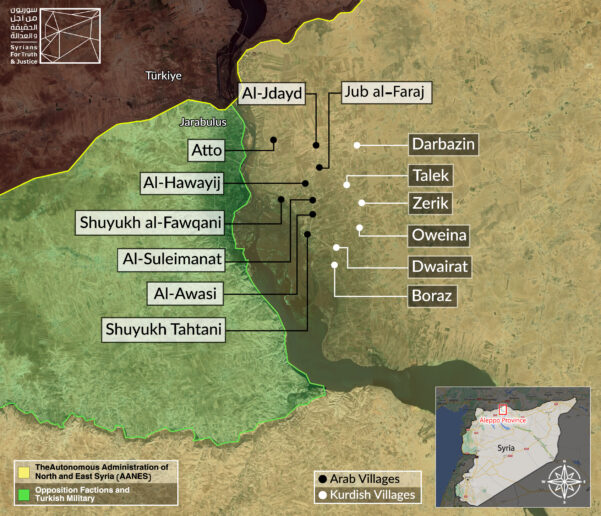

Image 1- A map showing the Arab villages, whose residents were denied a return, and the adjacent inhabited Kurdish villages. Credit: STJ.

-

People Displaced in Mass by Military Operations are Denied Return

Since the SDF took over Ayn al-Arab/Kobanî in the summer of 2015, it prevented Arabs of Arab and Kurdish-majority villages (adjacent to the Euphrates River separating areas of the SDF and the Syrian National Army) who were from returning home. The SDF justified the prevention by alleging that the villages are still full of mines or were security zones. However, testimonies obtained by STJ the purpose of this report, confirmed that the SDF pursued a selective policy, as it allowed certain residents to enter the villages temporarily to check on their homes and prevented others.

Notably, people displaced from the Shuyukh district are currently residing in Manbij and Raqqa, controlled by the SDF as well as Jarabulus held by the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA).

Sources met by STJ were unanimous in saying that people displaced from the two villages started submitting returning requests to the MMC and the Tribal Leaders’ Council in early February 2016. IDPs also organized protests for the same end but they were all repressed.

Mahmoud Alkhaled (a pseudonym), a displaced from Jubb al Faraj, testified to STJ:

“I hail from Jubb al Faraj village of Shuyukh Tahtani. When the conflict erupted between the SDF and the Islamic State (IS) in our area, we fled to Jarabulus while other locals headed to Manbij. After the end of the hostilities, we decided to return to our homes via a bridge that connects Jarabulus with Shuyukh Tahtani; nevertheless, we learned that the bridge was blown up by the IS. Thereafter, the SDF then issued a circular banning entry of civilians to the villages citing the existence of landmines and other explosive remnants of war. In 2017, we decided to return to our village through the Euphrates River, but we were warned that the SDF might target us, given we are coming from the areas of the opponent SNA. We tried to claim our right of return on every occasion. The latest justifications for the return banning were given by SDF official, who claimed that it is for security purposes and due to the fact that some of the IDPs supported the IS.”

On the mechanism for obtaining a permission to visit the villages, the source explained:

“Obtaining permission to visit the Shuyukh district requires filling out a form at the MMC headquarters, near al-Matahen Roundabout to the south of the city, with presenting an ID that proves the person is a local of the district. However, the MMC gives selective permissions and approvals on the pretext that the district remains a military zone.”

Qasem Thaher, (a pseudonym), a displaced from the village of Shuyukh Tahtani, testified to STJ:

“When the fighting began between the IS and the SDF, we left our homes and fled to Manbij, where we are still living because the SDF denied us the return despite the end of hostilities. In 2016, when things calmed down, we tried to return to our villages. However, the SDF checkpoints on the road did not allow people of Shuyukh Tahtani and Shuyukh al-Fawqani to pass. The checkpoint at the Qere Qozaq Bridge returned all IDPs.”

The source added:

“We made repeated attempts to return to our villages; in 2018, we tried to cross the bridge but the SDF fired on us and thus we turned back. In 2020, we went out in a big protest in Manbij, following news of bulldozing homes in al-Jadida village near Shuyukh al-Fawqani, to ask for clarifications as to why we denied return. The SDF met the protest with violence; it arrested dozens of participants and released them on the condition of signing a pledge not to demonstrate again.”

Mohammad Al Lohammad, a displaced from Shuyukh al-Fawqani testified to STJ:

“We fled hostilities in our village heading to Jarabulus. We stayed there for a short time before we went to Manbij where we resided until the battles against the IS concluded. In 2017, I decided with other young men to visit our village and see if it is safe to return with our families. However, SDF members at the Qere Qozaq Bridge checkpoint did not allow us to pass when they read on our IDs that we hail from Shuyukh al-Fawqani.”

Khaled al-Shuyoukhy (a pseudonym), a displaced from Shuyukh al-Fawqani confirmed to STJ that only certain people were allowed to visit the village and went on to say:

“The SDF allowed very few IDPs to visit their villages for hours only. However, none of Shuyukh al-Fawqani residents were allowed to enter it except for some notables who were permitted to visit it for a few hours. Furthermore, requests to bury the dead in the village are always rejected. On behalf of all IDPs of the Shuyukh district, I demand a visit of a UN delegation to the district. The delegation would examine the reality of the district’s situation and see if there are logical reasons to ban the return to its displaced population, whose number exceeds 60,000.”

-

Preventing the Return of Arabs in Particular

STJ heard matching accounts on the justifications provided by local military authorities for preventing displaced Arabs from returning to their villages. The authorities alleged that some of those displaced supported the IS against the SDF and that there were still left landmines in the area, which is frontline with the SNA. Meanwhile, ironically, the SDF allowed displaced Kurdish residents of neighboring villages to return.

In this respect, Yazan al-Shyoukhi (a pseudonym), a displaced from Shuyukh Tahtani residing in Jarabulus testified to STJ:

“There are Arab villages that have been evacuated due to the conflict, which are; Shuyukh Tahtani, Shuyukh al-Fawqani, al-Awasi, al-Jadida, Hawaij, Jubb al Faraj, and an-Atou. However, neighboring Kurdish villages did not see displacements, including al-Duwerat, al-Boraz, al-Awenah, Zark, Ta’alek, and Derbazin. Actually, only Arabs are denied a return.”

Ahmed al-Mustafa, a displaced from Shuyukh al-Fawqani residing in Jarabulus confirmed to STJ:

“The SDF continues to consider our villages as military zones despite the end of the military operations. We tried much to get the SDF to allow us to return, but the latter always refused. In 2018, we formed a delegation and went to Raqqa to meet the deputy commander of the SDF’s Euphrates Region, Najm Abu Ali al-Amiri. We had with al-Amiri a lengthy discussion during which the latter described the reasons why we still denied a return. He claimed that is because our villages are on the contact line with the SNA. We replied that the region has other villages, which are also contact lines but still inhabited. Thereby, he promised to forward our demands to the high command. It has been four years since then, we did not receive any response.”

In the same context, Khaled Al-Shyoukhi testified:

“On 20 April 2014, we were displaced from our village by the clashes between the SDF and the IS. However, when the SDF won the conflict and took over the area, it did not allow us to return, citing that the people of our village supported the IS. On 15 October 2017 and 17 February the same year, we submitted requests to the MMC to obtain return permission, but both requests were rejected under claims of left landmines in the village. On 19 June 2017, we formed a delegation and went to the MMC’s public relations officer, Haval Khalil Rasho. He told us that we cannot return to our villages, because we supported the IS during the conflict – this is absolutely untrue – and that there are fears of leaking the SDF’s military sites coordinates to the SNA in case of a return, especially since our villages are contact lines with the latter.”

-

Settling Kurds in Arab Villages

After years of being barred from returning to their villages, locals of the Shuyukh Tahtani and Shuyukh al-Fawqani were allowed to enter them temporarily to check on their property. Some locals were shocked to see Kurdish families residing in their homes and working in their fields. These locals inquired from the SDF about the reason for occupying their homes and fields, and the latter responded that the settled families are either those displaced from Afrin or relatives of fighters who fall in SDF battles.

Khaled al-Hammoud (a pseudonym) recounted to STJ:

“The SDF continued preventing us from returning home until 2022 when it permitted short visits to al-Awasi and Jubb al Faraj. Indeed, on 12 February, my father obtained a permit from the MMC to check on our home and land. My father was shocked to see strangers residing in the village’s houses, including mine and my brother’s. My father tried to inquire from those families how and why they were settled in the village; however, they told him to go to a military post in the village and ask there. In the military post, my father was told that the people who settled in the village are the families of fighters who fell in the SDF battles with the SNA and the Turkish Army or are IDPs from Afrin.”

The source added:

“On 20 April 2022, my father revisited the village under new permission from the MMC. He saw then the strangers residing in the village working in our fields. My father asked them how they assign themselves the right to do so, they answered that they took these fields as compensation for what they lost in Afrin after the Turkish occupation.”

According to the same source, more than 200 families from Afrin were settled in evacuated homes in al-Awasi, Jubb al Faraj, and Shuyukh Tahtani. A different source said the families remained in these villages for a few months and then relocated to other areas in Northeastern Syria.

Mohammed al-Mohammed (a pseudonym), a displaced from one of the Shuyukh villages residing in Manbij recounted to STJ:

“In 2018, the SDF permitted some notables to visit our village. The notables told us that some houses were used for military purposes, including mine; there were tunnels dug through them. Members of the SDF inhabit most of the houses in our village; actually, the whole village was turned into a military zone, under the pretext that it is adjacent to the contact lines with the SNA. However, this is just a mere flimsy argument.”

The source Qasem al-Thaher, suggested that the SDF aims at bringing about social and demographic change by denying the return to Arabs in particular. Al-Thaher explained:

“The SDF does not want us to return because it is working towards making our region of Kurdish identity. To this end, the SDF is settling Kurds in our homes and giving them our land to work in them. These practices will inevitably lead to a demographic change and thus they must be confronted and stopped.”

-

Legal Opinion

Prohibition of forcible displacement in situations of armed conflict is one of the main elements in international humanitarian law (IHL), which affirms that parties to a conflict must take constant care to spare the civilian population from the effects of hostilities. Thus, the recurring phenomenon of the displacement of the civilian population during armed conflict is the exception rather than the norm.

Nonetheless, evacuating civilians shall not considered a violation if it was an inevitable measure a party to a conflict must take to protect Nonetheless, evacuating civilians shall not be considered a violation if it was an inevitable measure a party to a conflict must take to protect civilians from an unavoidable grave danger. However, this lawful eviction must be a temporary situation during which the party to the conflict responsible for it must take all possible measures in order that the civilians concerned are received under satisfactory conditions of shelter, hygiene, health, safety, and nutrition and that members of the same family are not separated. Moreover, the property rights of displaced persons must be respected as well as their right to voluntarily return in safety to their homes or places of habitual residence as soon as the reasons for their displacement cease to exist.

Subjecting civilians to compelling factors, which leave them no other choice but to flee, is precisely the violation of the IHL. The compelling factors have several forms, which not only come under direct force; they may include threat, oppression, and abuse of authority.[1] The SDF’s seizing property in the areas that fall under its control contributes to complicating the process of the displaced civilians’ return and thus prolonging their displacement. Thereby, the SDF’s conduct goes against the lawful eviction conditions and is considered as an abuse of authority; one of the compelling factors.

The cases where forced displacement of the population or their continued displacement is claimed to be required by imperative military necessity are exceptional and must in no way be used to persecute displaced people. Furthermore, the alleged “imperative military necessity” must be must be subject to a careful and critical assessment of its necessity, legitimacy, and proportionality; meaning that the situation should be scrutinized most carefully as the adjective “imperative” reduces to a minimum cases in which displacement may be ordered. The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) emphasizes that imperative military reasons cannot be justified by political motives. For example, it would be prohibited to move a population in order to exercise more effective control over a dissident ethnic group. The discrimination against Arab families by denying them a return as confirmed by testimonies cited in this report reflects the situation defined by the ICRC. This discrimination is considered one of the forms of oppression and may amount to a crime against humanity if it is proven to have been committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack against any civilian population the in the sense of Article 7(1)(h) of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, which even classified the forcible transfer of population in itself as a crime against humanity.[2]

The displaced persons’ right to voluntary return in safety to their homes is guaranteed by international, most notably Rule 132 of the Customary IHL. However, the realization of this right required the controlling authorities in the displaced persons’ original places of residence to create the conditions and provide the means for their return, according to the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement. As such, the SDF’s invocation of security reasons or other military conditions to block the return of IDPs several years after the end of hostilities is not acceptable in the context of the imperative military reasons and is a failure by the SDF to enforce its obligations to create conditions for safe return.

In the same vein, seizing Arab IDPs’ property strengthens the possibility that the act of preventing the return of Arab IDPs could amount to a war crime. Under international humanitarian law, seizing private property is prohibited unless necessary for military operations.[3] That said, seizing the property of Arab residents as described by testimonies was not for military necessity. Settling SDF fighters in the IDPs’ homes is in no way necessary militarily. Moreover, compensating people displaced from other areas, such as Afrin, with IDPs’ private property is a clear violation of the IHL and the international human rights law (IHRL).

-

Syrian Law’s View

Practices of the SDF as described by testimonies cited in this report, not only violate international covenants and conventions but also the Syrian law in force and even the provisions of the AANES.

Confiscating private properties in the areas covered in this report and denying their owners access to them clearly violates Article 15 of the 2012 Syrian Constitution in force, which states:

“Collective and individual private ownership shall be protected in accordance with the following basis:

- General confiscation of funds shall be prohibited;

- Private ownership shall not be removed except in the public interest by a decree and against fair compensation according to the law;

- Confiscation of private property shall not be imposed without a final court ruling;

- Private property may be confiscated for necessities of war and disasters by a law and against fair compensation;

- Compensation shall be equivalent to the real value of the property.”

STJ has verified that none of the property confiscation victims was compensated. Preventing Arab owners from returning home and managing their properties, while allowing the Kurds in neighboring villages to do so, in addition to housing Kurdish families in the homes of Arab IDPs, constitutes a violation of the principle of equality stipulated in Article 33.3 of the current Syrian Constitution, which stipulates that “Citizens shall be equal in rights and duties without discrimination among them on grounds of sex, origin, language, religion or creed.”

The violations cited in this report violate the Syrian Civil Code No.84 of 1949 which affirms that no one may be deprived of his property except in cases determined by law, and in return for fair compensation (Article 770) and that the owner of a property has the right to all its returns, products, and attachments unless there is a text or agreement states the contrary (771). Furthermore, the Syrian Penal Code No. 148 of 1949 stipulates that anyone who does not carry a document of ownership or disposition and seizes either property in whole or in part shall be liable to imprisonment (Article 723). The same Code prohibits the entry of someone’s land or property without permission as it states in Article 557.1, “Whoever enters a house or dwelling of another person or structures annexed to the dwelling or house against that person’s will, as well as whoever stays in the aforementioned places against the will of whoever has the right to expel him/her from it, shall be sentenced to imprisonment for a period not exceeding six months.”

-

The AANES violates its own laws

Since the AANES’ Constitution, officially titled Charter of the Social Contract in Rojava (Syria) considers human rights international covenants and conventions as an essential part of it (Article 20), the practices and violations cited in this report shall be criminalized under it. Furthermore, Article 41 of the Charter states, “Everyone has the right to the use and enjoyment of his private property. No one shall be deprived of his property except upon payment of just compensation, for reasons of public utility or social interest, and in the cases and according to the forms established by law.”

The favoritism of certain citizens at the expense of others is a violation of Article 6 of the Charter, which stipulates that “All persons and communities are equal in the eyes of the law and in rights and responsibilities.”

Furthermore, the AANES’ Penal Code prescribes penalties for violations of property rights; it states in Article 141, “A penalty of imprisonment for one to two years shall be imposed on anyone who seizes property in whole or in part without carrying a document of ownership or disposition. The penalty shall be one and half a year to three years imprisonment if the act occurred by threatening or practicing violence against owners, by using a weapon, or by several persons collectively.”

The same Code considers the right to free expression and to peaceful demonstration a basic right of the population of AANES areas. However, the SDF violated this right when it dispersed peaceful protests with force arresting many participants and forcing them to sign pledges not to protest again.

[1] See for example ICTY, Prosecutor v. Radovan Karadžić, “Public Redacted Version of Judgment Issued on 24 March 2016”, IT-95-5/18-T, 24 March 2016, §§ 489-491.

[2] Rome Statute, Articles 7(1)(d) and 8(2)(e)(viii).

[3] ICTY, Prosecutor v. Gotovina et al., Case No. IT-06-90-T, Judgement (TC), 15 April 2011, § 1783.