“Syrians for Truth and Justice” organization, with the support of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), facilitated and organized several dialogue sessions, under the title of (“The Road Towards a New Syrian Constitution: How to Benefit from the Experiences of Other Countries?”). The aim of these dialogue sessions was to inform a diverse group of Syrians about the experiences of four different countries, some of which appear to have succeeded, to a great extent, in properly addressing the issue of diversity and inclusion during their constitution-drafting process, and others whose experience were not as successful, if at all. In some of these experiences, the failure to comply with the fundamental principles of the rule of law was even a politically motivated deliberate step towards discriminately excluding certain groups and systematically depriving them of some of their fundamental rights not only as groups but also as individuals.

The idea of these dialogues came as a continuation of an earlier effort in the form of a series of meetings that started in 2020, under the title of (“Syrian Voices for an Inclusive Constitution”), which aimed at promoting a more inclusive constitutional drafting process and ensuring the fair and proper representation of marginalized groups, communities and minorities. Subsequently, a set of papers were published in that regard. These papers respectively focused on the following themes:

- “The Formation and Responsibilities of the Syrian Constitutional Committee”

- “Syria’s Diversity Must be Defended and Supported by Law”

- “Transitional Justice and the Constitution Process in Syria”

- “Governance and Judicial Systems and the Syrian Constitution”

- “Socio-Ecological Justice and the Syrian Constitution”

In the 2021 sessions, the target groups were distributed mainly in the northeastern and western regions of Syria, considering gender and ethnic diversity – women were involved alongside men, and Kurds alongside Arabs, Yazidis, Assyrians, Armenians, Syriacs and other different ethnic groups. Emphasis was placed on individuals who had not participated in any similar meetings on constitutionalism and the constitutional drafting process in Syria.

This paper addresses the Lebanese constitutional experience. It is the second in a series of four such reports, approaching Lebanon, Turkey, and Bosnia and Herzegovina. (Read the Iraqi experience here).

In these papers such experiences will be introduced and some of their relevant aspects will be projected on the Syrian context. An objective comparison between each of these experiences and the Syrian on specific issues, will facilitate a better and more informed deliberation and consequently come up with more relevant recommendations as to how a more balanced and inclusive new Syrian constitution could ideally be drafted.

After several fruitful discussion sessions between participants and a few renowned academics and experts on the topic, “Syrians for Truth and Justice” has dedicated this paper to discussing the constitutional experience of Lebanon.

Looking at the political reality in many countries around the world and the most significant events in their history, such as wars, internal conflicts and revolutions that followed their emergence as independent states from colonial powers or after the fall of some empires, it becomes obvious that the newly forged artificial national identities in many of these countries with their current political borders does not inclusively represent all groups within their societies. As such, these identities did not reflect or conform to the desires of all the peoples residing in those regions; on the contrary, it seems that in most cases such identities exclusively reflect or represent that of the dominant majority or the most powerful group. Moreover, such an identity, be it ethnic, cultural, political, or religious would often case be (forcefully) imposed on the rest of society, while attempting to erase the original identities of the other groups and minorities with the aim of assimilating them into the single national identity of the majority or the most powerful. This tyrannical behavior would eventually lead to prolonged violent conflicts. In that regard, we are still witnessing the consequences of systematic acts or policies in the form of political movements calling for independence or civil wars.

During the past decade, there were several referendums in many regions around the world that called for a popular vote on independence and demanded the right of those peoples to self-determination, as in Catalonia, Scotland, and the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, followed by severe political and economic consequences for the peoples who called for their self-determination.

Many other issues, such as the acquisition of power by certain groups and their exercise of monopoly over drawing the main features of the broader national identity and imposing it on other groups within the society, are the most common and direct roots of some of the outstanding conflicts in most of the states that were formed in the first half of the last century (including Syria, Iraq, Turkey). All these issues have constitutional dimensions that must be understood before seeking plausible solutions for them, and any proposed solutions to these issues, especially during any form of transitional justice, must include a cohesive and comprehensive constitutional treatment at the very first place.

How did the dictatorships in Syria, Iraq and other countries come to power, and manage to rule for decades without competition? Is such an authority considered legitimate and how can we measure their legitimacy? Where does the legitimacy of power lie, where does it derive from and when is it lost? What is meant by the concept of “the rule of law” and how could it be achieved? What institutions are required? What powers and authorities such institutions could have? What is the role of the citizen and the concept of citizenship in all of this?

The above questions were the starting points and main focus of the discussions in the dialog sessions, through which the quest was to create a deeper understanding of the concepts of “the constitution” and the legitimacy of authority,” before delving into the specific chosen constitutional experience to extract what could be benefited from or avoided in any future attempt to draft a Syrian constitution, in a way that would make it compatible with the values of the twenty first century and in full respect of the principle of the rule of law as the basis for its legitimacy.

Before comparing the constitutional experiences of the selected countries and delving into the concepts, standards, rights, or freedoms contained in their constitutions, it was very useful to return to the theories and intellectual currents that were considered the origins of modern constitutionalism. To that end, the seventeenth century AD was the most appropriate starting point to serve the desired purpose of this project.

In the second half of the seventeenth century, several social and political theories emerged, which are known nowadays as the “social contract theories”, which paved the way for the emergence of intellectual currents that had a profound impact on the concepts of power, citizenship, and legitimacy as we know them today. Among the most important of these theories are the theories of British philosophers such as Thomas Hobbes and John Locke and the French writer and philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau. The theories proposed by these philosophers were based on different assumptions about human nature and the ideal model of a society in which the relationship between individuals and the authority holding power is determined by the notion of a “social contract.” Through such a hypothetical contract the ruler’s individuals confer legitimacy over the ruler as an authority to exercise power over the society in order to safeguard the interests of the society as individuals as well as groups in the best possible way. Some of these theories established intellectual currents that inspired and contributed to the formulation of the principles of the French Revolution in 1789 as well as the American Revolution in 1765.

The vast majority, if not all, states in the world have a so-called constitution, which is considered the supreme law in those countries. Despite the great resemblance between the connotation the term “Constitution” gives in each of these countries as well as the common understanding of the notion and what it generally entails, it may, however, vary in its forms and differ in what it includes from one country to another.

Often, Constitutions are formed after major events that have an impact on, or even shape, the national identity (the consideration of a group as a people). Defining or re-defining moments in the history of human groups marking a new beginning or a significant turning point, is also known as a “Constitutional Moment”. The best examples of these major events may be wars, such as World War I and World War II, or revolutions and independence movements, such as the French Revolution and its values, which later inspired the formation of constitutions throughout Europe, and the American Revolution, which led to independence from the dominating colonial power that was then the United Kingdom.

Contrary to popular belief, a constitution is not necessarily written or compiled into a single document, as it may be based on binding international or regional agreements as well as unwritten customs or practices. For example, the United Kingdom, whose constitutional laws have not yet been collected in a single document.

As for most countries, they do have a constitution that has been compiled in writing into a single document. In general, such a document, with what it includes of laws and rules, is rigid and difficult to modify, and is characterized by a somewhat superior nature, as it determines the shape of the state and its system of government. Such a document includes a set of rules that govern the formulation of laws, the structure of government and its institutions, and the separation and assignment of powers within the state. In addition to the above, one of the most important functions of the constitution is to define and protect the fundamental freedoms and rights of citizens as groups and individuals.

Even in those countries that have a single document called the constitution, what these constitutions stipulate may be completely different from their counterparts in other countries in terms of the distribution of powers and the separation between them, as well as the designation of rights and duties assigned to individuals and institutions, in addition to defining the form of the state and its system of government.

To know the form of the state or the system of government adopted by any state, it is self-evident to refer to the constitution of that country and simply look at how powers are distributed within the state structure. This assessment consists of the following two basic steps. First: the vertical distribution of powers and authorities between the center and the periphery of that state, thus defining the shape of the state, whether it is centralized or decentralized at all levels, such as Syria, which is considered a highly centralized state, where we see all the powers and authorities concentrated and centered in the capital, unlike the Republic of Iraq, which has adopted the federal model. Second: The distribution and horizontal separation between the basic institutions within the power structure in the state, such as the legislative, judicial and executive authorities, and the determination of the size of the powers granted to them at the expense of other of those institutions, which distinguishes the system of government, whether it is, for example, presidential such as the United States of America, or parliamentary such as the Netherlands and Canada.

Some of these constitutions attach more importance to the concept of national identity than others, and it usually appears in the form of a narrative story in its preamble, such as the Chinese constitution. In most cases, this story is the embodiment of the thought of a particular group in a position of power over other groups of the same society. Others, on the other hand, may not even contain a preamble, but rather enter directly and practically into the core of articles that stipulate basic rights, such as the Dutch constitution.

Some constitutions were keen to include articles and paragraphs that are not subject to amendment, in order to protect these constitutions from (easily) being changed during political fluctuations as a natural response to their historical experiences, as in the German constitution. As such, the German Constitution stipulates in the third provision of Article 79 that it is not allowed to submit or accept any amendment to those articles of the Constitution related to the federation of the German state as a union and the right of the states to participate in the legislative process. Accordingly, it may be necessary at times for these constitutions to show rigidity as a form of protection for some basic concepts and principles from changing easily, but it may also be used to perpetuate the authority of a person or a particular group or racist or discriminatory concepts against minorities, groups, and other individuals within their societies, which may even cause conflicts in the future due to social, cultural or political changes. Herein lies the importance of our awareness of the sensitivity and difficulty of drafting or amending a document such as the constitution of a country so as to include a more inclusive and more just concept of citizenship, which would be primarily based on equality and respect for others under the principles of the rule of law, not only for the time of drafting but also capable of remaining remain valid and viable in the future.

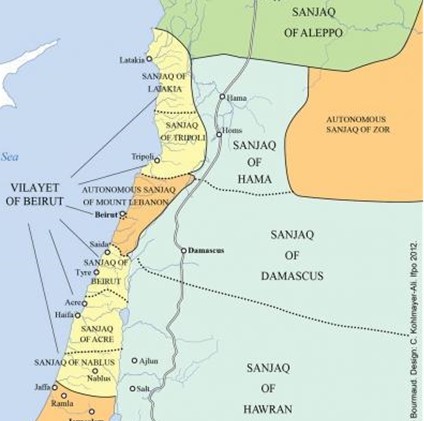

Lebanon became part of the Ottoman Empire by 1517 and developed its own political system until the 18th century.[1] Even during the period under Ottoman rule, European influence grew in the region through trade. The Maronites, an ethnoreligious Christian group, were especially influenced by the French due to their integration into the Roman Catholic religious structure. In the 19th century, the Christian communities expanded due to mission schools established by the French and Americans which upset the traditional religious balance. Most of Lebanon was under direct Ottoman control, except for the autonomous Sanjaq of Mount Lebanon (it was also placed under strict control during World War I).[2]

Figure 1: Ottoman administrative division 1914.[3]

The present 1926 Constitution of Lebanon draws on the traditions of Mount Lebanon. For example, when the Statute for the Mountain was promulgated in 1861 by the International Commission, an Administrative Council was established.[4] The Council equally represented the important religious communities, and hence can be historically linked with the present system of confessionalism and equal representation in the Chamber of Deputies (the equivalent legislative body). Further, Lebanon was to be administered by a Christian Ottoman governor who would have full executive authority while being assisted by the Council.[5] Such an institutional setup resembles the one adopted when the 1926 Constitution was promulgated: the executive power was vested in the president with the assistance of ministers. Additionally, the president was conventionally Christian (mostly Maronite). Lastly, all inhabitants of Mount Lebanon were deemed equal before the law, a feature which is also reflected in the 1926 Constitution (Article 7).[6]

-

French Mandate

Lebanon was occupied by the Allied forces at the end of World War I and placed under the French administration.[7] The French mandate was formalized in 1923, a decision that was approved by the Maronites since they were favored under the mandate system. As prewar Lebanon was expanded into Greater Lebanon, the ethnic distribution changed so that Christians and Muslims each made up around 50% and the Maronites no longer were the majority.[8] Lebanon’s borders were drawn to suit France’s colonial interests and did not reflect the will of the majority of the population.[9] Significantly, a large section of the population wanted to live under a greater Syrian or Arab state and did not favor French rule or independence.[10] The tension among groups regarding their sense of national belonging persisted until the breakout of the civil war in 1975.

-

Independence

As services and education improved in Lebanon under the French administration, national consciousness developed among the middle class of Beirut and eventually led to the push for independence.[11] In the 1943 elections, the Lebanese Nationalists won, and Bishara al-Khuri was elected president. In the same year, al-Khuri and the prime minister Riad Al Solh came to an informal verbal understanding deemed as the “National Pact” which was a founding document for the independent state of Lebanon.[12] While independence was proclaimed on November 22, 1943, the British and French withdrew their troops only in 1945, and independence was completed in 1946 when Lebanon became a parliamentary democracy.[13]

In terms of the ethnic distribution of the population, the last official census was carried out in 1932, hence only estimates are available regarding the present distribution. According to the 2021 CIA World Factbook, 61.1% of Lebanon’s population are Muslims (30.6% Sunni, 30.5% Shia, and smaller percentages of Alawites and Ismailis), 33.7% Christians (mostly Maronites but also Eastern Orthodox, Protestant, Melkite Catholic, etc.) 5.2% are Druze and other small minorities.[14]

-

Civil War

The civil war lasted from 1975 until 1990. It was preceded by two main causes of political and social polarization. First, Charles Hélou, president of Lebanon 1964-1970, undertook reforms that led to increased social mobility and urbanization.[15] However, as groups moved to urban centers such as Beirut, they were not sufficiently integrated. Contrasts persisted between rural migrants and upper as well as middle urban classes. Thus, a belt of impoverished settlements that had developed by the mid-1970s around Beirut served as a source of political instability. Secondly, as Palestinian guerrillas moved into Lebanon after being expelled from Jordan, the balance of the population was shifted until in 1973, Palestinians formed one-tenth of the population.[16] Since Palestinians were mostly landless and poor, their interests overlapped with the poor, rural, and mostly Muslim groups. Thus, the emergence of a Palestinian “state within a state” further undermined the precarious balance between social groups in Lebanon.

The beginning of the war is usually dated to April 13, 1975, when Christian Phalangists attacked a bus taking Palestinians to a refugee camp.[17] The incident took place in the context of escalating violence between Maronite Christians and Muslims due to the increased prominence of Phalangists. The Druze sided with the Palestinian resistance and the Palestine Liberation Organization during the war, and favored Pan-Arabism.[18] The Druze, under the Progressive Socialist Party led by Kamal Jumblatt, fought with leftists and Palestinian parties against the Lebanese Front, mainly made up of Christians (Maronites in particular).

Two main factors interfered with the peace process during the civil war, namely, the external interference in the conflict (mainly by Syria and Israel) and power struggles within sectarian communities that undermined negotiations. Eventually, a cease-fire was achieved in September 1989 by a tripartite committee involving Algeria, Morocco, and Saudi Arabia, and the Taif Agreement was signed. An arrangement was made that the Syrian forces would remain in Lebanon for up to two years and assist the new government with security which was opposed by General Aoun of the Lebanese army. The civil war ended after October 13, 1990, when Syrian troops attacked General Aoun and forced him into exile.[19]

6.1. Prominent Features

The two most prominent features of the Constitution are its French underpinnings and its focus on balancing the interests of various religious and ethnic groups.[20] Since the Constitution was drafted under the French Mandate system it is not surprising that it resembled French constitutional law. The Constitution not only borrowed from French texts but also from the Belgian Constitution (1830) and the Egyptian Constitution (1923) which were in turn influenced by French constitutional practice. The content of Chapter Two which outlines the rights and duties of the people is mainly derived from the French Declaration of Human Rights. The centrality of the principles of liberty and equality in the Constitution is indebted to the French influence. For example, Article 7 provides equality before the law, Article 8 guarantees individual liberty, Article 9 emphasizes complete freedom of conscience, and Article 15 guarantees ownership rights.[21]

However, the Constitution also inherited the practice of excessive liberalism and subsequent weakness of the parliamentary system of the former Third French Republic.[22] The parliamentary form of government, initially including a bicameral legislature, led to continual instability. Lebanon was mostly ruled by frequently changing coalition cabinets due to shifting public opinion and political alliances. The bicameral legislature, adopted by the 1926 Constitution, consisting of a Chamber of Deputies and Senate (the Senate was abolished in 1927) proved to be too expensive, slow, and weak for Lebanon.

Secondly, while the Lebanese Constitution provides for the equality of all citizens and aims to secure national unity, it does not ignore the local traditions of different religious denominations.[23] Article 24, amended by the Constitutional Law of 17 October 1927, 21 January 1947, and 21 September 1990, states that the Chamber of Deputies shall have equal representation of Christians and Muslims, proportional representation among confessional groups within the two religious groups, and proportional representation among geographic regions.[24] Yet to reflect the goal of national unity, Article 27, as amended on October 17, 1927, and January 21, 1947, states that a member of the Chamber shall represent the whole nation.[25] The whole political organization of the State is organized around equitable representation of all religious denominations and proportionate distribution of public offices and representative seats.[26]

6.2. Legislative Branch

The legislative power is vested in the Chamber of Deputies (Article 16).[27] The Chamber is made up of 128 directly elected Deputies, and seats are divided equally between Christians and Muslims (Article 24).[28] The seats are further subdivided between the two groups. The Muslim confessional communities include Sunni, Shia, Druze, and Alawite. The Christian confessional communities include Maronite Christian, Greek Orthodox, Greek Catholic, Armenian Orthodox, Armenian Catholic, Evangelical and Minorities.

The Chamber of Deputies has the power to: [29]

- Confirm or disapprove of the formation of the Cabinet (Article 64);

- Oversee the performance of the Cabinet and its ministers, hold ministers accountable and vote them out of office when necessary (Articles 37, 66, 68, 69);

- Elect the President of the Republic (Article 49);

- Ratify certain categories of international treaties and agreements (Article 52);

- Approve the annual budget of the State (Article 32).

6.3. Executive Branch

The executive power is vested in the Council of Ministers (Article 17), however, the president also enjoys nominal executive power. Members of the Council of Ministers are not members of the Parliament, but members of the parliament can serve as ministers.[30] The Council is appointed by the President, in agreement with the prime Minister (Article 53). The Council of Ministers is headed by the Prime Minister whose powers are outlined in Article 64 and include the following:

- Participate with the President in the formation of the Government,

- Present Government’s policy before the Chamber of Deputies,

- Sign decrees with the President,

- Oversee the work of the Council of Ministers.

The Council of Ministers has the following powers under Article 65:

- Set the general policy for the Government,

- Execute laws and regulations as well as supervise civil, military and security administration,

- Appoint and dismiss state employees,

- Dissolve the Chamber of Deputies upon the request of the President.

The President is “elected by secret ballot and a two-thirds majority of the total votes of the Chamber of Deputies.” (Article 49) The powers of the president are outlined in Article 53, however, under the Taif agreement he was stripped of his constitutional powers and was left only with one significant power – to appoint the members of the Cabinet together with the Prime Minister.[31]

6.4. Judicial Branch

The Judicial Branch is addressed in a single article, Article 20, which stipulates that:

“Judicial power is exercised by the courts of all levels and jurisdictions within the framework prescribed by law that shall provide the necessary guarantees to both judges and litigants […] Judges are independent in the exercise of their duties and their decisions and judgments shall be rendered in the name of the Lebanese people.”[32]

However, the standard of the independence of the judiciary has not been achieved due to the enacted laws.[33] First, the judiciary suffers from the interference of the executive branch through the appointment, promotion, and reassignment of judges by the Ministry of Justice. Second, the Constitutional Court, established under the 1990 amendment, only has limited jurisdiction and access to its review. Only the President, the Speaker, the Prime Minister, and a minimum of ten deputies, as well as heads of recognized religious communities have the right to petition the court for review.

6.5. Electoral System

Since Lebanon is a parliamentary system, the Chamber of Deputies is elected directly by the people. To vote, a Lebanese citizen must be above 21(Article 21) and belong to the recognized confessional groups of either Christians or Muslims.[34] The Lebanese electoral system has five key elements:

- “The right to stand is confessional: Seats can only be contested by candidates who are from the confession it is allocated to.

- The right to vote is non-confessional: Voters can vote for all available confessional seats, regardless of the voter’s confessional group.

- Voters have more than one vote: Lebanon uses multi-member electoral districts. Voters can vote for as many candidates as there are seats available.

- Voters vote with a single ballot paper: On a single ballot paper, a voter chooses the names of candidates they wish to vote for. A voter may choose to use only some of the votes they are entitled to.

- It is a plurality/majority system: Where there is only one seat for a confession, the seat is won by whichever candidate from that confession has the most votes. Where there is more than one seat for a confession, the seats are won by as many candidates from that confession who have received the most votes.”[35]

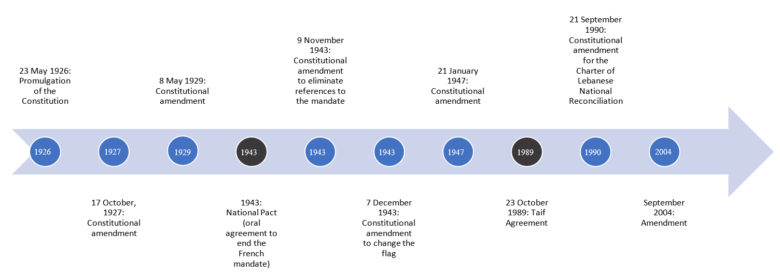

7.1. 23 May 1926 Promulgation:

In July 1925 the French authorities appointed a commission to prepare a draft constitution which was promulgated by the French High Commissioner on May 23.[36] The Constitution provided “for the establishment of a parliamentary form of government based on the democratic principles of protection of individual rights and freedoms, separation of powers, and the rule of law.”[37] The Lebanese political system was transformed into a quasi-religious federation or a confessional regime due to the requirement of religious representation in the legislature and public employment.

Even though Article 1 of the Constitution declared Lebanon to be an independent state within its territorial boundaries, Article 90 provided that “mandatory power must preserve its rights and duties under article 22 of the Charter of the League of Nations and the terms of the mandate.”[38] Thus France had the right to suspend the Constitution, shut down the Chamber of Deputies, elect the President and dismiss the Cabinet.

7.2. 17 October 1927 Amendment:

Due to the inefficiency of a bicameral legislature for a small country like Lebanon, the amendment abolished the upper house or Senate (see amendments of Articles 16, 18, 19, 22, 23, 24, and others). Instead, the amendment provided that the legislative power shall be exercised only by the Chamber of Deputies. The Chamber was divided into two categories: members who are elected by Decree No. 1307 of 1922 or any subsequent law and those appointed by the president (however, a March 1943 constitutional amendment required that all members of the Chamber be elected).[39]

7.3. 8 May 1929 Amendment:

The 1929 Amendment dealt with a deputy’s right to raise the question of no-confidence, selection of ministers from the Chamber, powers of the President, and the election procedures for the position. The amendment affected Articles 28, 37, 49, 55, 69. Article 28 was amended so that ministers could be selected from the Chamber or outside the Chamber and the requirement as to what proportion of ministers should come from the Chamber was abolished.[40] The presidential mandate was prolonged from four to six years.[41]

7.4. 1943 National Pact:

The National pact can be understood as a compromise between Christians and Muslims to deal with the national identity crisis of Lebanon. Since the beginning of the French mandate, there was a lack of consensus among Muslims who identified with Arabs/greater Syria and Christians who saw themselves as Lebanese and wanted a close relationship with the West. As a solution, Bechara el-Khouri and Riad el-Solh proposed to “acknowledge the Arab identity of Lebanon and accept the legitimacy and independence of the Lebanese state as a final homeland for all of its citizens.”[42] Thereby Christians would give up their allegiance to the West and instead accept an Arab identity, while Muslims would cease to demand an Arab state and accept a Lebanese identity.

Following the National Pact and independence, the customary practice of religious representation was expanded to assign certain governmental offices to certain communities. The Presidential role was assigned to a Maronite Christian, Prime Minister to a Sunni Muslim, and the President of the Chamber of Deputies to a Shi’i Muslim.[43] Although, there exists contention over whether this expansion of confessionalism was part of the National Pact.[44] As evidence, it is mentioned that on October 22, 1946, an Orthodox Christian was elected as the President of the Chamber of Deputies as opposed to a Shi’i Muslim.[45] Even though the Army Chief of Staff is generally assigned to a Druze, the Druze were largely alienated by the new assignment of positions.[46] Nonetheless, the Druze have been able to address their political grievances through the Progressive Socialist Party and its representation in the parliament.

7.5. 1943 Amendments:

The amendment adopted on the 9th of November 1943 removed all references to the mandate from the Constitution.[47] Additionally, the practice of religious representation was expanded because of a July 1943 decision by the representative of the French Mandate. It was decided that religious representation in the Chamber of Deputies would follow the ratio of 6:5 (Christians to Muslims). The amendment by the Constitutional Law of 7 December 1943 changed the Lebanese flag.

7.6. 21 January 1947 Amendment:

The purpose of the amendment was to allow for the re-election of the President of the Republic Bishara al-Khuri (also cited as Khoury). The Constitution was temporarily amended to allow the President to succeed himself and secure a second six-year term.[48]

7.7. 23 October 1989 Taif Agreement:

The surviving members of the Lebanese parliament, elected in 1972, met in Taif, Saudi Arabia to accept a constitutional reform package. The Taif agreement proposed “a modest restructuring of the confessional regime to placate the warring factions” and end the civil war.[49] The agreement aimed to address the issue of a confused national identity at the root of the civil war. Overall, the Taif Accord stipulated a gradual elimination of confessionalism.

7.8. 21 September 1990 Amendment:

The 1990 amendment aimed to implement the provisions of the Taif Agreement. Based on its requirements, the following amendments were adopted:

- No authority that contradicts the pact of coexistence can be considered legitimate (Preamble),

- The executive power of the president was reduced and, instead the power was vested in the Council of Ministers (Article 17),

- The Cabinet needed two-thirds of a vote on all major decisions (Article 65),

- The Constitutional Court was created (Article 19),

- The division of parliamentary seats, cabinet posts, and senior administrative positions was changed from 6:5 (Christian to Muslim) to an equal ratio (Article 24),

- A Senate which represents all religious communities would be created once the Chamber of Deputies is no longer elected on a confessional basis (Article 22). [50]

7.9. September 2004 Amendment:

Prior to the amendment, the UN Security Council passed a resolution aimed at Syria and demanded that foreign troops leave Lebanon.[51] However, Syria dismissed the resolution. As a result, the Chamber of Deputies voted in September 2004 to amend the Constitution to extend President Émile Jamil Lahoud’s term in office by 3 years. The amendment once again raised the question of Lebanese sovereignty and Syria’s interference. The vote was “taken under Syrian pressure, exercised in part through Syria’s military intelligence service.” As a result, Lahoud was granted another term by the Lebanese parliament under pressure from Syria.[52]

During the session that was held in 2021 on the Lebanese constitutional experience, several participants agreed on the similarity of the Syrian and Lebanese experiences because both countries suffered from conflict, external interference, and distributing power on a sectarian basis. Also, the participants believed that it is essential to reach an inclusive political solution, to achieve democracy, and to ensure that all members of society enjoy their rights without discrimination, regardless of their race, color, affiliation, and gender.

Moreover, the participants referred to the richness of the Lebanese experience in terms of political pluralism and diversity of its political parties. They stressed that pluralism requires taking several measures into account, including the quota rule or positive discrimination (allocating some seats to certain groups to avoid permanent isolation) and the autonomous administration of certain matters, in addition to the supremacy of federal systems.

In this context, the participants discussed how to implement political pluralism in Syria. They believed that it is necessary to benefit from other constitutions and to apply the principle of freedom of parties (which is a general principle that requires inclusive participation). Also, some participants pointed out that in order to overcome the differences, it is important to address them and to set several rules to prevent their exploitation by any party. An inclusive pluralism is necessary for any constitution to succeed.

During the session, the democracy in Lebanon was discussed. Some participants agreed that it was inherited in the history of Lebanon. For example, when the Arab countries were under Ottoman rule, Lebanon formed councils composed of all groups. Lebanon’s existence required the division of power between various sects and the respect of their freedom of belief and peculiarity of education.

Furthermore, the participants argued that the problem of Lebanon and Syria is not in the constitution but rather in the governance system and the lack of security, especially that no constitution is well applied —even in the most modern societies— unless a country enjoys its sovereignty. The Lebanese constitution is non-sectarian and defined in a civilized system that includes absolute freedom of belief. However, although the Lebanese constitution is one of the richest in the world, it is the worst in terms of implementation. Moreover, participants stressed the importance of gathering historical constitutional experience in Syria as a starting point for the consolidation of several basic principles.

According to the participants, the Lebanese constitution includes high standards. It emphasizes on the fact that Lebanon is a unified State and on the importance of preserving the privacy of all society components (in terms of personal status and education systems), maintaining the balanced composition of the Parliament (Muslims and Christians), and redistributing duties between the President of the Republic and the Parliament. Moreover, the constitution is superior to other texts (including religious and sectarian text). Also, the constitution stipulates that the people are the source of authority, and that the freedom of belief is absolute.

On the other hand, the participants discussed that Lebanon paid a high price to end the conflict because the Syrian forces remained in Lebanon and practically ended the State’s sovereignty. Also, because of the lack of justice as the warlords received a comprehensive amnesty. Therefore, what happened in Lebanon was not a real reconciliation —which should not be repeated in Syria— especially that Lebanon was affected by the political sectarianism and the lack of democracy (like the unfair elections and the domination of intelligence services). Further, Lebanon suffered from a political and social gap related to its militias. Therefore, the state of law lacked stability which led to the emptiness of sovereignty and the collapse of the constitutional system.

Moreover, several participants agreed that a federal system might be the solution for Syria, given that its population is diverse, and its geography is suitable for this system. However, it is essential to have consensus and a real intention of all groups to amend the constitution, maintain a unified army, and to stop any external interference.

Based on the dialogue session held by Syrians for Truth and Justice on the constitutional experience in Lebanon, the following recommendations are made:

- The Syrian constitution shall emphasize on the unity of the State, the preservation of the particularity of diverse social components, and the absolute freedom of belief.

- To provide for pluralism and protection of rights, in addition to the quota rule or positive discrimination by allocating some seats to certain groups to avoid their permanent isolation. Moreover, to exclude sectarian pluralism because it may be a tool to undermine the national identity and to open the way for some regional and international countries to implement their agenda in Syria.

- To hold awareness-raising and capacity-building workshops on the constitution and political participation, and to always include the various groups of Syrian people.

Annex I

List of Sources

“Chronology for Druze in Lebanon,” Minorities at Risk, 16 July 2010,

http://www.mar.umd.edu/chronology.asp?groupId=66001.

“Lebanon,” Central Intelligence Agency, 2021,

https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/lebanon/#people-and-society.

“Lebanon profile – Timeline,” BBC News, 25 April 2018,

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-14649284.

“Lebanon – Politics – 2004-8,” Global Security,

https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/lebanon/politics-2004.htm.

“The Constitution,” U.S. Library of Congress, http://countrystudies.us/lebanon/76.htm.

Habachy, Saba. “The Republican Institutions of Lebanon: Its Constitution,” The American Journal of Comparative Law, Vol. 13, No. 4, Autumn, 1964, pp. 594-604.

“Minorities at Risk Project,” Assessment for Druze in Lebanon, 25 March 2005,

https://www.refworld.org/docid/469f3aa91e.html.

Neveu, Norig. “The Impact of Ottoman Reforms,” Atlas of Jordan: History, Territories and Society, edited by Myriam Ababsa. Presses de l’Ifpo, 2013, pp. 198-201,

https://books.openedition.org/ifpo/5002.

Ochsenwald, William L. , Barnett, Richard David , Kingston, Paul , Khalaf, Samir G., Maksoud, Clovis F. and Bugh, Glenn Richard. “Lebanon,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 10 Mar. 2021,

https://www.britannica.com/place/Lebanon.

Saliba, Issam. “Lebanon: Constitutional law and the political rights of religious communities.” Law Library of Congress, Global Legal Research Center, 2010.

Tabbarah, Bahige. “The Lebanese Constitution,” Arab Law Quarterly, Vo.12, No.2, 1997, pp. 224-261, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3381819.

“The Lebanese Electoral System,” International Foundation for Electoral Systems, March 2009,

https://ifes.org/sites/default/files/ifes_lebanon_esb_paper030209_0.pdf.

Traboulsi, Fawwaz. A history of modern Lebanon. Pluto Press, 2012.

[1] Ochsenwald, William L., Barnett, Richard David, Kingston, Paul, Khalaf, Samir G., Maksoud, Clovis F. and Bugh, Glenn Richard. “Lebanon,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, 19 November 2023, https://www.britannica.com/place/Lebanon.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Neveu, Norig. “The Impact of Ottoman Reforms,” Atlas of Jordan: History, Territories and Society, edited by Myriam Ababsa. Presses de l’Ifpo, 2013, pp. 198-201, https://books.openedition.org/ifpo/5002.

[4] Habachy, Saba. “The Republican Institutions of Lebanon: Its Constitution,” The American Journal of Comparative Law, Vol. 13, No. 4, Autumn, 1964, p. 596.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ochsenwald, William L., Barnett, Richard David, Kingston, Paul, Khalaf, Samir G., Maksoud, Clovis F. and Bugh, Glenn Richard. “Lebanon,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 19 November 2023, https://www.britannica.com/place/Lebanon.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Traboulsi, Fawwaz. A history of modern Lebanon. Pluto Press, 2012, p.75.

[10] Ibid., p.80.

[11] Ochsenwald, William L., Barnett, Richard David, Kingston, Paul, Khalaf, Samir G., Maksoud, Clovis F. and Bugh, Glenn Richard. “Lebanon,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 19 November 2023, https://www.britannica.com/place/Lebanon.

[12] Traboulsi, Fawwaz. A history of modern Lebanon. Pluto Press, 2012, p.109.

[13] Ochsenwald, William L., Barnett, Richard David, Kingston, Paul, Khalaf, Samir G., Maksoud, Clovis F. and Bugh, Glenn Richard. “Lebanon,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 19 November 2023, https://www.britannica.com/place/Lebanon.

[14] “Lebanon,” Central Intelligence Agency, 2021,

https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/lebanon/#people-and-society.

[15] Ochsenwald, William L., Barnett, Richard David, Kingston, Paul, Khalaf, Samir G., Maksoud, Clovis F. and Bugh, Glenn Richard. “Lebanon,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 19 November 2023, https://www.britannica.com/place/Lebanon.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] “Chronology for Druze in Lebanon,” Minorities at Risk, 16 July 2010, http://www.mar.umd.edu/chronology.asp?groupId=66001.

[19] Ochsenwald, William L. , Barnett, Richard David, Kingston, Paul, Khalaf, Samir G., Maksoud, Clovis F. and Bugh, Glenn Richard. “Lebanon,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 19 November 2023, https://www.britannica.com/place/Lebanon.

[20] Habachy, Saba. “The Republican Institutions of Lebanon: Its Constitution,” The American Journal of Comparative Law, Vol. 13, No. 4, Autumn, 1964, p. 599.

[21] Tabbarah, Bahige. “The Lebanese Constitution,” Arab Law Quarterly, Vo.12, No.2, 1997, pp. 226-267,

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3381819.

[22] Habachy, Saba. “The Republican Institutions of Lebanon: Its Constitution,” The American Journal of Comparative Law, Vol. 13, No. 4, Autumn, 1964, p.600.

[23] Ibid., p.601.

[24] Tabbarah, Bahige. “The Lebanese Constitution,” Arab Law Quarterly, Vo.12, No.2, 1997, p.230,

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3381819.

[25] Ibid., p.231.

[26] Habachy, Saba. “The Republican Institutions of Lebanon: Its Constitution,” The American Journal of Comparative Law, Vol. 13, No. 4, Autumn, 1964, p.601.

[27] Tabbarah, Bahige. “The Lebanese Constitution,” Arab Law Quarterly, Vo.12, No.2, 1997, p.228,

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3381819.

[28] “The Lebanese Electoral System,” International Foundation for Electoral Systems, March 2009, https://ifes.org/sites/default/files/ifes_lebanon_esb_paper030209_0.pdf.

[29] Saliba, Issam. “Lebanon: Constitutional law and the political rights of religious communities.” Law Library of Congress, Global Legal Research Center, 2010, p.4.

[30] Ibid., p.5.

[31] Ibid., p.11.

[32] Tabbarah, Bahige. “The Lebanese Constitution,” Arab Law Quarterly, Vo.12, No.2, 1997, p.229,

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3381819.

[33] Saliba, Issam. “Lebanon: Constitutional law and the political rights of religious communities.” Law Library of Congress, Global Legal Research Center, 2010, p.7.

[34] The Lebanese Electoral System,” International Foundation for Electoral Systems, March 2009, https://ifes.org/sites/default/files/ifes_lebanon_esb_paper030209_0.pdf.

[35] Ibid.

[36] “The Constitution,” U.S. Library of Congress, http://countrystudies.us/lebanon/76.htm.

[37] Saliba, Issam. “Lebanon: Constitutional law and the political rights of religious communities.” Law Library of Congress, Global Legal Research Center, 2010, p.1.

[38] Ibid., p.8.

[39] Ibid., p.3.

[40] Tabbarah, Bahige. “The Lebanese Constitution,” Arab Law Quarterly, Vo.12, No.2, 1997,

https://www.jstor.org/stable/3381819.

[41] Traboulsi, Fawwaz. A history of modern Lebanon. Pluto Press, 2012, p.90.

[42] Saliba, Issam. “Lebanon: Constitutional law and the political rights of religious communities.” Law Library of Congress, Global Legal Research Center, 2010, p.9.

[43] Habachy, Saba. “The Republican Institutions of Lebanon: Its Constitution,” The American Journal of Comparative Law, Vol. 13, No. 4, Autumn, 1964, p.601.

[44] Saliba, Issam. “Lebanon: Constitutional law and the political rights of religious communities.” Law Library of Congress, Global Legal Research Center, 2010, p.10.

[45] Ibid.

[46] “Minorities at Risk Project,” Assessment for Druze in Lebanon, 25 March 2005, https://www.refworld.org/docid/469f3aa91e.html.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Ochsenwald, William L. , Barnett, Richard David , Kingston, Paul , Khalaf, Samir G. , Maksoud, Clovis F. and Bugh, Glenn Richard. “Lebanon,” Encyclopedia Britannica, 19 November 2023, https://www.britannica.com/place/Lebanon.

[49] Saliba, Issam. “Lebanon: Constitutional law and the political rights of religious communities.” Law Library of Congress, Global Legal Research Center, 2010, p.10.

[50] Ibid., p.11.

[51] “Lebanon profile – Timeline,” BBC News, 25 April 2018, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-14649284.

[52] “Lebanon – Politics – 2004-8,” Global Security, https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/lebanon/politics-2004.htm.