Executive Summary

On the 60th anniversary of the 1962 special Census of al-Hasakah, Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) is delving into the deprivation of nationality (statelessness), which continues to cast a shadow over the lives of several groups within diverse Syrian communities, inside and outside the country.

In this report, STJ addresses the grave repercussions of the issue, highlighting the ongoing plight of thousands of Syrian Kurds, who remain deprived of citizenship and are called maktumeen.

In addition to raising the voices of maktumeen, whose suffering pre-dates the Syrian conflict, which now has been ongoing for over 11 years, STJ sheds light on emergent and conflict-induced patterns of statelessness, which threaten the fates of the children of many Syrian refugees.

-

Maktumeen

In 1962, the Syrian government (SG) carried out a special census in al-Hasakah province, in northeastern Syria, which is home to a Kurdish majority.[1] In the aftermath of the one-day measure, a large number of Syrian Kurds were stripped of Syrian citizenship and divided into two categories:

- Ajanib al-Hasakah (foreigners), comprising the registered stateless individuals, who were granted red cards for identification.

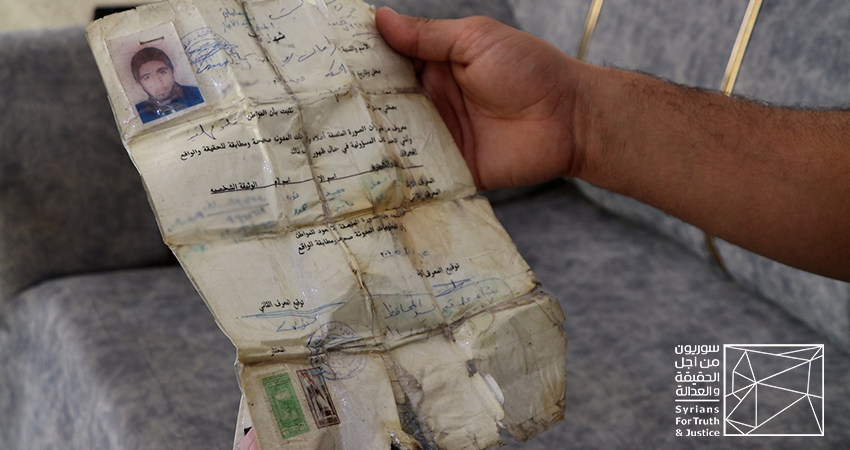

- Maktumeen, the unregistered stateless individuals, who were allocated identification certificates (ICs).

While documenting this ongoing dilemma, STJ received access to exclusive information from official sources in the Personal Status Department of al-Hasakah in 2018. The information reveals that nearly 517,000 individuals grappled with statelessness between 1962—the year of the census, and 2011—the year the SG granted citizenship to a large number of Syrian Kurds under Legislative Decree No. 49.[2] Among these were over 171,000 maktumeen, who were denied access to citizenship even under the decree, which applied to ajanib exclusively.

The rough numbers recorded in 1962 indicate that approximately 120,000 Kurdish men and women were immediately stripped of citizenship, while nearly 300,000 persons turned stateless over the decades following the census.[3]

Using the statistics collected in 2018, STJ learned that over 50,000 maktumeen have succeeded in “rectifying” their legal statuses. They succeeded in changing their category from maktumeen to ajanib and ultimately obtained Syrian citizenship.

Despite these successes, STJ’s monitoring and documentation efforts indicate that an estimated 150,000 Kurds continue to be denied their right to citizenship when this report was composed in October 2022. This segment consists of about 20,000 ajanib and over 120,000 maktumeen.[4]

Notably, statelessness does not only deprive maktumeen of their civil, political, economic and cultural rights established in International covenants and instruments, but also jeopardizes their very being. Maktumeen struggle with invisibility because their existence as individuals is unacknowledged in Syria.[5]

In response to the issue of statelessness, the SG made a statement that: “In 2011, they were keen on addressing numerous cases in accordance with the Civil Status Law promulgated under Legislative Decree No. 26 of 2007 and its subsequent amendments, executive instructions, and their amendments,” after it was amended by Law No. 20 issued on 23 October 2011.

As of 2017, the SG amended the law four times and its executive regulations nearly 10 times, the last of which was provided by decision No. 97/M.N. issued on 11 April 2017.

In a related context, a member of the Syrian People’s Council posted a document by the Syrian Ministry of Justice on Facebook on 1 February 2021.[6] The document defines the steps governing the naturalization of maktumeen, saying that the proceedings go through six stages, the last of which is obtaining security approval.

Several human rights activists and lawyers who oversaw the files of their maktumeen clients report that the citizenship proceedings are quite complex and that the approval for granting citizenship to a maktum is a pure “security decision”.

The document of the justice ministry also demonstrates that the decision to grant a maktum citizenship remains based on each case’s merits, at odds with the provisions of the 2011 Legislative Decree No. 49, which put an end to the statelessness of ajanib in a collective manner.

-

Refugee Children

Keeping tabs on the administrative challenges facing Syrian refugees in host countries, STJ documented several cases of children who remain unregistered with Syrian civil registration centers. Child refugees in Turkey, Egypt, Iraqi Kurdistan, and Lebanon are at risk of statelessness because they lack documents that corroborate their nationality. This, in turn, threatens to strip them of all their basic rights.

These children are out of the official records because their parents must register their marriages to be able to register births, a proceeding many asylum-seeking couples cannot carry out. The correlation between marriage and birth registration is established in article 28 of the Civil Status Law No. 13 of 2021, which prescribes that: “It is prohibited to register a birth from an unregistered marriage until the marriage is duly registered.” The same provisions are echoed by the Civil Status Law No. 26 of 2007.[7]

Syrian couples fail to register their marriages and, as a result, the birth of their children for several reasons, primarily because they are either internally displaced or refugees. Additionally, the fear of persecution by the security services in the case parents decide to return to Syria and the exorbitant money they have to pay in bribes to set into motion the registration proceedings and obtain related documents are factors that hamper the administrative cycle. Related to the high costs, STJ documented several cases of birth registration after parents paid official departments lucrative bribes.

STJ also corroborated the registration of several children in countries of refuge, but who nonetheless remained unregistered with civil status departments in Syria at the time of reporting, in early October 2022.

Even though official statistics on Syrian child refugees, who are unregistered with local civil registration centers, remain contested regardless of the host countries where they are currently based, the available numbers are expected to increase due to the lingering conflict in Syria and the lack of a solution to the statelessness issue.

-

Other Victims of Statelessness

While the patterns of statelessness in Syria can be roughly divided into two time-based categories, pre-2011 and post-2011, each of these categories covers various forms of statelessness, based on the affected group. [8]

Before 2011, statelessness was limited to Kurds stripped of citizenship during the 1962 census, children of unrecognized lineage, children of Syrian women married to non-Syrians, children of political opponents, and the members of a few nomadic tribes.

After 2011, statelessness became rife among other groups. According to several sources, including the Syrian Initiative to Combat Statelessness, statelessness is haunting the children of Syrian women married to foreign fighters—who backed either sides to the conflict or joined the ranks of jihadist armed groups, children whose parents are unknown—due to the death or detentions and disappearance of one or both parents, children born of rape in detention facilities or at security checkpoints, and children of parents who lost their identity documents when forced to flee their homes during hostilities, or while shifting their locations during displacement waves.[9]

Recommendations

The deprivation of nationality results in an individual’s deprivation of his/her legal personality, and a set of rights that protect human existence and dignity, such as the right to move inside and outside the country, access to education, healthcare, work, property and participation in public life. To address these adverse implications, STJ recommends:

- Inscribing the supremacy of international treaties and agreements ratified by Syria into the new Syrian constitution, especially instruments related to human rights and fundamental freedoms, including the right to acquiring a nationality.

- Inscribing that citizenship is the right of every Syrian into the new constitution and that a Syrian may not be stripped of this right by birth for any reason. Additionally, inscribing into the constitution that only an independent judiciary has the power to strip an individual of nationality, when obtained by meeting conditions set up by the law, and through a final court ruling, while stressing that the penalty should remain individual, not targeting the children of the convict or his/her relative, and ensuring that the reasons for revoking citizenship are clearly defined in the law.

- Passing a law that addresses the issue of Syrian Kurds deprived of citizenship under the unfair census of 1962, especially maktumeen.

- Amending the existing Syrian Nationality Act in a manner that achieves gender equality with regard to nationality, and gives the Syrian mother the right to pass on her Syrian nationality to her children, just like the father.

- Putting pressure on the SG to facilitate registration procedures for Syrian children born during the Syrian conflict, especially displaced and refugee children. This requires a re-examination of the status of the Syrian security services, and the broad powers they are granted without any legal justification.

- Exerting pressure on the SG to recognize registration documents of Syrian marriages and births, issued by the institutions of the countries where these civil events occurred.

To read the report in full as a PDF, follow this link.

[1] “Syrian Citizenship Disappeared”, STJ, 15 September 2018 (Last visited: 4 October 2022).

[2] The decree consisted of three articles:

Article 1: individuals who are registered as ajanib in the al-Hasakah province shall be granted Syrian nationality.

Article 2: the Minister of the Interior shall issue the decisions containing the executive instructions to this decree.

Article 3: This decree shall enter into force on the day of its publication in the Official Journal.

[3] “Group Denial: Repression of Kurdish Political and Cultural Rights in Syria”, HRW, 26 November 2006 (Last visited: 5 October 2022).

[4] Several months after the 2011 Legislative Decree No. 49 was passed, news was circulated that a ministerial decision is issued, which provides for treating maktumeen as ajanib in terms of access to citizenship. However, several maktumeen reported that when they visited civil registration centers, the centers did not deny the news and confirmed that the decision was indeed issued, but that they were not sure which official entity was exactly assigned the execution of its terms.

[5] “Decades of Statelessness & the Absence of Basic Rights”, STJ, 6 July 2021 (Last visited: 4 October 2022).

https://stj-sy.org/en/decades-of-statelessness-the-absence-of-basic-rights/

[6] Khalil, Abdulrahman (in Arabic). Decision by the Ministry of Justice about Maktumeen. Facebook, 1 February 2021. (last visited: 5 October 2022)

[7] “The Civil Status Law No. 26 of 2007” (in Arabic), the Syrian Ministry of Interior (last visited: 5 October 2022).

http://www.syriamoi.gov.sy/portal/site/arabic/index.php?node=55333&cat=1831&

[8] STJ will dedicate a separate and extensive report covering other patterns of statelessness inflicted upon diverse Syrian groups, especially the patterns which transpired after 2011.

[9] For further information, see: al-Tabshi, Rana. “Humans without Rights” (in Arabic), The Syrian Initiative to Combat Statelessness, 2021 (last visited: 5 October 2022). https://lb.boell.org/sites/default/files/2021-11/%D8%A8%D8%B4%D8%B1%20%D8%A8%D9%84%D8%A7%20%D8%AD%D9%82%D9%88%D9%82.pdf