Executive Summary

“They refused to hear a word. They sought to arrest any Syrian and get their thumbprint on the voluntary return document [. . .] whether willingly or not.”

Syrian refugee Mustafa said. He is a victim of the large-scale refoulement campaign the Turkish authorities are waging against Syrians under the guise of countering “irregular migration”. The campaign started in early July 2023, shortly after the Turkish presidential elections ended.

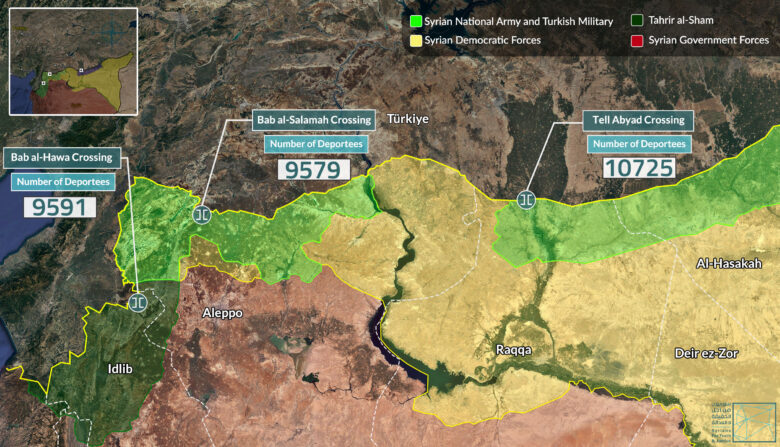

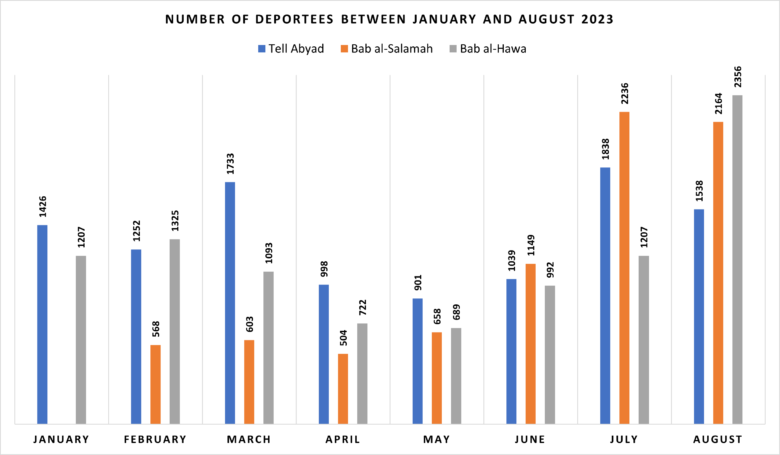

Between January and August 2023, the Turkish authorities have forcibly deported 29,895 Syrian refugees and asylum seekers through three border crossings: Tell Abyad, Bab al-Hawa, and Bab al-Slamah.

The Tell Abyad crossing ranked first in the number of deportations, having witnessed the illegal returns of 10,725 refugees, according to an informed source.

The Bab al-Hawa crossing came in second with 9,591 such returns, which have been reported on their official Facebook page, while the Bab al-Salamah crossing came in third, as it channelled 9,579 deportations, according to a second informed source.

The testimonies “Syrians for Truth and Justice” (STJ) collected for this report show that the new campaign—which the Turkish authorities claim is aimed solely at “irregular” Syrian refugees and asylum-seekers—is accompanied by multiple violations, including arrest, administrative detention for months without informing the refugees of the reasons or allowing them to engage a lawyer, beatings in removal centers, and other inhuman or degrading treatment. The testimonies also corroborate that Turkish authorities continue to force refugees held in those centers to sign the “voluntary return” papers and deport even those with legal documents, including refugees who possess the “temporary protection” document (Kimlik) and work permits.

Additionally, these recent testimonies show that among the forcibly deported are women and their children, who were left without breadwinners; children unaccompanied by their parents; elderly refugees; and persons with critical health issues, who were denied necessary healthcare and medications in removal and detention centers, even though they hold residence permits for medical treatment purposes issued by the Turkish authorities.

Notably, according to the testimonies, the larger segment of Syrian refugees and asylum seekers are forcibly deported through the Tell Abyad Border Crossing against their wishes, destined to geographical isolation with neither family support nor basic resources. Tell Abyad remains underserved for hosting deportees.

The forced deportations—the majority of which are collective—violate Turkish Law 6458 on Foreigners and International Protection (LFIP), issued in April 2013. The law grants Syrians “temporary protection in Türkiye, ensures their non-refoulment, and guarantees their stay until safety is established in their original countries.” One of the report’s sources told STJ that he witnessed the deportation of 300 Syrians on the same day. He was one of them.

Moreover, the Turkish authorities have instructed the administration of one of the border crossings to use the term “departures” in reference to the expulsions of Syrian refugees from Türkiye, insisting on their claims that the refugees’ movement through the border is not forced deportation but rather “voluntary return”.

Furthermore, the Turkish authorities deny acts of violence attributed to police officers in removal and detention centers. In an interview with Syrian TV—which addressed brutality by the police commissioned to capture “irregular migrants”—the newly assigned Turkish Minister of Interior, Ali Yerlikaya, stressed: “These are individual acts that do not represent the [police] institution.”

Image 1: Map designed by STJ showing the three border crossings through which Turkish authorities are forcibly deporting Syrians, as well as the number of deportations they carried out between January and August 2023.

Image 1: Map designed by STJ showing the three border crossings through which Turkish authorities are forcibly deporting Syrians, as well as the number of deportations they carried out between January and August 2023.

In an official statistic, the Directorate General of Migration Management announced that 58.758 Syrians returned in a “voluntarily, safe, and dignified” manner in 2022, bringing the total number to 539.332 returns since they started refugee repatriation measures in 2019.

Addressing the new administrative severity against Syrian refugees, on 22 July 2023, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) warned “that many Syrian journalists are liable to be jailed, abducted or even killed if they are sent back to Syria. Türkiye must protect them.” Additionally, the RSF called on “the Turkish authorities to adhere strictly to the principle that no refugee should be sent back to a country where they would be in probable danger.”

In this report, STJ sheds light on the details of the new deportation campaign, flagging the political and social factors that render it a source of terror for the Syrian refugee community in Türkiye. The report, thus, addresses the fierce Turkish presidential race—during which the issues of refugees and normalization of relations with the Syrian government were used as a card to appease an agitated public; the upsurge in anti-Syrian sentiment, which is one of the campaign’s drivers; and the Turkish authorities’ claims that deportation destinations are “safe”.

In this report, STJ sheds light on the details of the new deportation campaign, flagging the political and social factors that render it a source of terror for the Syrian refugee community in Türkiye. The report, thus, addresses the fierce Turkish presidential race—during which the issues of refugees and normalization of relations with the Syrian government were used as a card to appease an agitated public; the upsurge in anti-Syrian sentiment, which is one of the campaign’s drivers; and the Turkish authorities’ claims that deportation destinations are “safe”.

Within this context, STJ presents 10 direct and extensive testimonies obtained for this report. STJ interviewed two sources informed of the workings of the border crossings, which today serve as portals to likely peril, in addition to eight forcibly deported refugees. The Turkish authorities deported all eight even though several held documents that warranted their legal stay in Türkiye or struggled with personal challenges that made them especially vulnerable and deserving of protection. Notably, STJ has changed the names of the deportees to maintain their security.

Legal Opinion

Article 26 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties provides that “[e]very treaty in force is binding upon the parties to it and must be performed by them in good faith.” The principle of good faith is one of the general principles of international law and entails a sense of fidelity to and respect for the law; the lack of concealment, deceit, and fraud; and the sincere conviction that one is operating in conformity with the law. Türkiye’s attempt to circumvent the principle of non-refoulement—one of the contractual and customary provisions of international law—by portraying the deportations they are carrying out as voluntary—voluntariness being one of the conditions that make the return of refugees non-coercive—contradicts the principle of good faith within the meaning relayed above.

The concept of voluntariness is firmly rooted in the principle of non-refoulement since “coercion” in essence runs counter to free will and informed decisions that result in voluntary return.[1] Consequently, the negative push factors of the host State, Türkiye, consisting of exerted psychological, material, and legal pressures, denote that any refugee’s decision to return—apart from actual deportations—lacks the elements of voluntariness. This, therefore, makes their return a forced return, for which Türkiye bears primary responsibility. This is so because Türkiye has forced those who decide to return under these circumstances to choose to return to a place where there is a real fear of persecution, driven by the push factors applied to them.

The attempt to reduce the concept of voluntariness—including all the conditions and criteria playing into it—by coercing those forcibly deported to sign a “voluntary return” paper reflects in practice Türkiye’s failure to implement the provisions of international law in good faith. By way of reference in this context, the cessation clauses in Article 1(C) of the 1951 Refugee Convention should not automatically apply to all persons seeking international protection,[2] as they may still have a well-founded fear of persecution or compelling reasons not to return stemming from previous persecution.[3] Thus, the principle of good faith implies that host States should not take advantage of the possibility that the general circumstances in the country of origin—that drove individuals to seek asylum—have changed to deny international protection to all those who pursue such protection. It rather implies that the host State should take into account the individual circumstances of each of them so that their return would not amount to refoulement.

Considering the conditions Türkiye puts Syrian refugees through—as presented in this report—to compel them to return to Syria or to deport them directly to Syria, a consistent pattern of practices transpires in which abuse or deliberate misinterpretation of certain legal provisions, on the one hand, and human rights violations, on the other, intersect.

In accordance with the principle of sovereignty in international law, States shall be at liberty to enact laws, legislation, and domestic procedures that they deem appropriate to regulate the affairs of their nationals and aliens under their jurisdiction. Therefore, States can grant their citizens exclusive access to certain rights protected in international human rights law instruments, such as the right to participate in political life in accordance with Article 25 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, while restricting aliens’ access to these rights. However, other restrictions imposed by States on non-citizens cannot be justified to the extent that they amount to a prohibited form of discrimination.[4] Any other restrictions on non-citizens must be necessarily justifiable and do not in themselves violate other rights protected by international human rights law. In Türkiye, such legal frameworks include Act No. 6458, known as the Law on Foreigners and International Protection. Article /54/, first paragraph, item (D), of the law provides for the deportation of individuals who violate public order or security from Türkiye. Under the law’s Temporary Protection Regulation, there are Articles 33 and 8. Under Article 33, Syrians in Türkiye are obliged to comply with orders issued by the Directorate General of Migration Management or Provincial Administration, stipulating that contrary attitudes and behavior constitute a violation of these obligations, which are essential for establishing public order. On its own, Article 8 provides that a breach of public order is one of the grounds for the abolition of temporary protection status.

These articles link in several ways the concept of “public order” with the right of the Turkish authorities to take such measures as they deem appropriate against Syrians, including the restriction of freedom of mobility through obliging Syrians to reside in specific areas and the prohibition of movement and travel, except with prior authorization, which involves complex procedures. They also confer on themselves the right to take measures up to deportation to Syria in light of violations of those regulations. Notably, in line with the principle of non-discrimination, foreigners on Turkish territory should have the right to liberty of movement and freedom to choose their residence under Articles 12(1) and (2) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. The exception under which the law permits the restriction of these rights is subject to the conditions set forth in paragraph 3 of the same article: “The above-mentioned rights shall not be subject to any restrictions except those which are provided by law, are necessary to protect national security, public order (ordre public), public health or morals or the rights and freedoms of others, and are consistent with the other rights recognized in the present Covenant.”

The United Nations Commission on Human Rights has clearly stated that banning individuals from traveling internally without a permit is not considered compatible with the requirements of the third paragraph, which demands that there be a clear and proportionate necessity in the proceedings for the necessity or interest that these proceedings purportedly seek to protect.[5] Consequently, the penalties or measures responding to violations of the laws restricting these rights should be proportionate in the first place to their necessity, and, of course, non-refoulement as an international norm cannot be regarded as proportionate to the purported necessity of such restrictions. Even though the maintenance of public order is included in the third paragraph as one of the grounds for derogation, it is for States to define and specify its criteria and necessities, provided that this does not affect the enjoyment of other rights and is always done in good faith. Therefore, the maintenance of public order must always be understood as the conditions and rules that guarantee the functionality of society and must be in place so that individuals can enjoy their rights and freedoms[6] and not otherwise become a pretext for restricting those rights and freedoms.

Türkiye uses its national laws of international protection to make the term “public order” a broad concept that it can use to perpetrate and justify a number of violations against Syrians, such as unjustified restrictions on movement, overly complicated legal procedures, arbitrary arrest and denial of the right to an effective remedy, fair and effective judicial proceedings, torture and inhuman treatment, and finally refoulement in violation of a rule of customary international law.

Within this perspective, with regard to those who have been able to clarify their legal status in Türkiye by obtaining a temporary protection card (kimlik) or other regular residence permits, it appears that Türkiye invokes the most basic forms of infractions to forcibly deport them to Syria, in blatant contravention of Article 13 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and, of course, the principle of non-refoulement. The article stipulates that “[a]n alien lawfully in the territory of a State Party to the present Covenant may be expelled therefrom only in pursuance of a decision reached in accordance with law and shall, except where compelling reasons of national security otherwise require, be allowed to submit the reasons against his expulsion and to have his case reviewed by, and be represented for the purpose before, the competent authority or a person or persons especially designated by the competent authority.”

A quick comparison of the cases cited in the report—especially those where the deported are legally eligible for residence in Türkiye—demonstrates that the only element upheld by the Turkish authorities is that the decision was made in accordance with the law 6458 discussed above, considering its shortcomings and contraventions. Notably, Article 13 does not address the content of the law on the basis of which a deportation order is made since the law itself must be in conformity with the State’s obligations under international law to ensure that no arbitrary deportation is carried out.[7] On the other hand, all those mentioned in this report and other human rights reports were denied the right to an examination that considers the individual merits of their cases and not one based on decisions aimed at entire groups, as well as the right to have access to all means to enable them to obtain an effective remedy, including by challenging the deportation/refoulment decision through transparent and effective judicial or other proceedings.[8]

As to other cases where, according to Article 13 of the Covenant, the legal residence requirement may not apply, if the individuals’ entry or residence is subject to dispute in accordance with the laws in force in the State, any decision leading to their expulsion or deportation must be made in proportion to the essence of Article 13. “It is for the competent authorities of the State party, in good faith and in the exercise of their powers, to apply and interpret the domestic law, observing, however, such requirements under the Covenant as equality before the law (art. 26).”[9] In this context, the European Court of Human Rights, whose jurisdiction applies to Türkiye, has found that the decision to deport/refouler international protection applicants who have not legally entered the territory of the State and whose presence there is illegal is a violation of the right to an effective remedy within the meaning of Article 13 of the European Convention on Human Rights since the deportation decision was taken while their appeals were still pending before domestic courts.[10]

Additionally, and underscoring the principle of non-refoulement that remains applicable under all circumstances, Türkiye is obliged under international contractual and customary law not to return any Syrian to where they may be subjected to persecution, torture, and inhuman treatment, danger to life and human dignity, or other serious violations of their rights. Therefore, Türkiye’s maintenance of the geographical scope of the 1951 Refugee Convention and its non-applicability to Syrians seeking international protection on its territory cannot be invoked to claim the legality of their deportation to Syria. In any event, Türkiye must objectively assess all the elements of voluntariness, safety, and dignity necessary for the return of refugees, not only the conclusions based on the decline in military operations but also, inter alia, the economic and living conditions, family and social ties, the possibility of reintegration, and the standing of laws enforced and situation of human rights in the areas to which the refugees will return.

Before relying on all these elements and conditions, Türkiye must act to stop the negative push factors that sometimes force Syrian refugees to make uninformed decisions to return. Lastly, Türkiye must facilitate UNHCR’s involvement in all details concerning the return of refugees, including but not limited to the exercise of international protection functions to oversee the well-being of refugees and international protection applicants; respect the UNHCR’s leadership role in promoting, facilitating, and coordinating voluntary repatriation; guarantee UNHCR have full access to refugee populations wherever they may be to ensure the aspect of voluntariness applies to their returns; allow UNHCR to ascertain the voluntary nature of repatriation in relation to individual refugees and to large-scale movements; organize a comprehensive information campaign to enable refugees to make their decisions with full knowledge of the facts; facilitate arrangements and engage UNHCR to ensure that refugees have access to accurate and objective information on conditions in the country of origin; conduct interviews, advise, and register potential returnees; and organize safe and orderly return movements and appropriate reception arrangements.[11]

The New Deportation Campaign

The Turkish authorities launched their most brutal deportation campaign in the wake of the new appointments made by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan following his victory in the presidential elections that ended on 28 May 2023. In the new cabinet, Ali Yerlikaya was appointed Minister of the Interior as a successor to Süleyman Soylu, and the entire staff of the Directorate General of Migration Management was changed.

In an interview with the Turkish Hürriyet media outlet on 9 July 2023, Yerlikaya stated that “the fight against irregular migration is one of the top priority areas we have identified as a ministry,” adding that the campaign covers all 81 provinces of Türkiye, not just Istanbul, and is being conducted with the participation of police, gendarmerie, and coast guard units. He noted further that the country will see a “clear difference” in four to five months, during which the campaign will continue. He added that the term “irregular migration” covers the illegal entry, stay, departure, and unauthorized employment of foreigners in Türkiye.

In a statement to journalists following a meeting of the Council of Ministers in the capital, Ankara, on 22 August 2023, Yerlikaya announced the ministry transformed “Istanbul into a pilot area, and we established mobile migration points,” with reference to new measures to combat “irregular migration”.

Syria TV relayed the details of an interview with Yerlikaya on the Turkish channel A Haber in which he explained the mechanisms underlying the “mobile migration points.” He said the points were provided with “the biometric fingerprint reading system, which helps to verify registered and unregistered persons.” However, despite this system, STJ has documented the deportations of many Syrians registered under the “temporary protection” status.

In addition to these points, the interior ministry deployed drones to assist the campaign’s operations, “which covered various locations such as sea boats, public transportation, parks, and gardens, as well as abandoned buildings and public spaces” in Istanbul. These operations “accounted for approximately two-thirds of the national average of similar actions conducted throughout the country.”

In tandem with the tightened security checks, Yerlikaya announced that foreigners will be denied residence permits “in municipalities where they make up over 20 percent of the population,” as well as “the closure of 1169 out of 32,000 districts in Türkiye to foreigners for preventive purposes.” This measure is in keeping with the migration and harmonization plans declared by the Turkish authorities in February 2022, which blocked registration in primary districts in Istanbul, such as Esenyurt, known as major assembly points for Syrian refugee families

Horror Washes Over Syrians

The sweeping campaign spread terror within the Syrian community, particularly in Istanbul. The province has the highest density of Syrian refugees, hosting 531,966 Syrians, according to numbers published by the Refugee Association in March 2023.

Since the campaign followed a highly polarized and intense presidential race in which the Syrian refugee file and the restoration of relations with the Syrian government were weaponized, it is being interpreted as an indication of an actual shift in Türkiye’s policy towards the Syrian presence. During the primary and runoff elections, politicians included plans to deport Syrians in their promotional campaigns and post-election agendas in an effort to win over a high-strung and critical electorate.

Kemal Klçdarolu, the opposition’s candidate, who heads the Republican People’s Party (CHP), had the strongest rhetoric against refugees. His campaign started under the slogan “We will never make Türkiye a repository for refugees,” while his electoral posters during the second round told voters that “Syrians will go!”. For his part, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, candidate for the Justice and Development Party (AKP), attempted to adopt a relatively different and more pragmatic rhetoric on the refugee issue during the first electoral round. However, as the race dragged to a second ballot, he stated: “From the very beginning, we supported the voluntary and safe return of refugees. Some 560,000 refugees have returned,” noting that “Türkiye aims to secure the return of nearly one million refugees and perhaps more in the first phase of the new brick home projects” during an interview with Turkish TRT.

In the context of normalization, the then Turkish Foreign Minister, Mouloud Jawish Oglu, announced “the start of cooperation with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to return Syrian refugees to their areas,” pointing to the “necessity of sending Syrian refugees to areas under the control of the Syrian Government,” during an interview on 21 May 2023.

Erdoğan’s victory did not bring the Syrian community any reassurance. Many Syrians, especially workers, still resort to the survival mechanisms they developed in response to previous forced deportation campaigns. In a report published on 2 June 2023, Enab Baladi newspaper documented how Syrian workers avoid central squares in Istanbul to evade police patrols and deportation buses deployed in vital areas such as Aksaray and Esenyurt.

Notably, the lack of access to “work permits” makes the majority of Syrian workers vulnerable to deportation, owing to the reluctance of most employers and the inability of the lower percentage to obtain the required authorizations. In a report by the Danish Refugee Council, published in August 2021, the official statistics, collected between 2016 and 2019, show that “a total of 132,497 work permits were issued to Syrians registered in Türkiye, which includes renewals of already existing work permits,” while “[i]t is estimated that approximately 1 million Syrians are working informally without legal protections and rights and 45 percent of Syrians under temporary protection are living below the poverty line.”

While deepened fears continue to overwhelm Syrians, the campaign offered proof that the electoral deportation and normalization discourse was not mere propaganda but rather a frame for the new government’s policies—especially since Türkiye will witness decisive mayoral elections next year. The resumption of severed Syria-Türkiye relations was a primary discussion point during the 20th Session of the Astana Talks, held on 20-21 June 2023, of which Türkiye is a guarantor State along with Russia and Iran. Additionally, Erdoğan blessed the objectives of the campaign in a statement to journalists on 13 July 2023. He said, “Our citizens will soon witness tangible changes on irregular migration.”

Forced Deportations Masked as Voluntary Returns

In an interview with Al Jazeera in August 2023, the Turkish interior minister, Ali Yerlikaya, said: “All that is being said about the forced deportation of Syrians to northern Syria is not true, and there are those who use social media and other forms of media to incite falsehoods and unfavourable assumptions about us. We are keeping tabs on them.” He added: “We have a signed document from every Syrian citizen who leaves for the other side of the border, proving they left Türkiye willingly.”

However, the ten testimonies STJ collected for this report reveal that Syrian refugees and asylum seekers in Türkiye have no “will” or right to determine their fate.

Syrians without Agency

In an exclusive account, a source (no. 1) informed of the workings of the Tell Abyad Border Crossing stressed that the Turkish authorities are today even depriving Syrians of their right to choose the destination of their deportation, highlighting the adverse impact of the authorities’ coercive practices on the lives of refugees they are illegally removing from Türkiye. The source said:

“During the past deportations, [refugees] were allowed to choose a crossing. Therefore, those who wanted to go to the Autonomous Administration’s areas chose the Tell Abyad crossing. People, originally from Aleppo’s northern and western suburbs and Idlib, chose either the Bab al-Hawa or Bab al-Salamah crossing. Right now, deportations are carried out randomly, and the deportee is never asked about his/her preferred destination.”

The coercive destinations of the deportees—most of whom are being returned to unfamiliar areas in northern Syria—leave them with a single choice, namely smuggling. The deportees are resorting to smugglers to reach places where they have relatives or to return to Türkiye, where their families still are. The source added:

“Because a significant portion of those deported to Tell Abyad are not from the area or do not wish to remain there, they resort to smuggling through Manbij. There is an undeclared agreement between the [Syrian] National Army (SNA) and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), mediated by smugglers who work for both sides. People are relocated from Tell Abyad and Ras al-Ayn (Serê Kaniyê) to Aleppo’s northern countryside through Manbij in exchange for others in the Autonomous Administration’s areas who want to cross to the SNA’s. Smuggling from Tell Abyad and Ras al-Ayn costs between 300 and 500 USD. However, for deportees who wish to return to Türkiye, Tell Abyad remains the best choice in terms of cost and faster passage. There has been noticeable trafficking of deportees from Syria to Türkiye from Tell Abyad city. Of course, the trafficking to Türkiye is run by SNA-affiliated smugglers.”

Notably, smuggling carries several risks for deportees eager to reunite with their families in Türkiye. On top of these threats is death at the hands of the Turkish Border Guard. In a June 2022 report, STJ documented four cases of torture and four deaths by direct shooting perpetrated by the border guard against Syrian asylum seekers in the first five months of the year.

Also addressing Turkish border guard brutality in an April 2023 report, Human Rights Watch said that “border guards are indiscriminately shooting at Syrian civilians on the border with Syria, as well as torturing and using excessive force against asylum seekers and migrants trying to cross into Türkiye”, adding that “[they] viciously beat and tortured a group of eight Syrians who were attempting to cross irregularly into Türkiye. A man and a boy died in Turkish custody, while the others were seriously injured.”

About the geographical scope of the deportation campaign and the groups of Syrians it targets, the source added:

“An extensive and large-scale campaign is carried out in Istanbul. The majority of the deportees are coming from there. Additionally, there is a parallel campaign in Türkiye’s southern areas, in Şanlıurfa, Gaziantep, and Kilis, to counter smuggling attempts by those wishing to enter Türkiye or deportees wanting to return.”

He added that the campaign is targeting a wide range of Syrians, not only those who do not possess kimliks. He said:

“The situation now is as follows: deportations are carried out against people without kimliks, with kimliks, and those with infractions, even if their infractions are minor. Before this campaign, those who violated the travel permit regulations were not deported to Syria. Rather, they were transferred to Kilis Camp for a day. After that, they would return to their province of registration and do weekly visits to the [migration department] and thumbprint sign [documents proving they are present in the province]. Currently, those who violate these regulations are being sent to the Kilis Camp for a day or two and then deported to Syria.”

The source added:

“Today (on 17 July 2023), a batch of about 72 people arrived at the crossing. I wandered among them and asked [about their legal status]. All of them did not possess kimliks. Additionally, I saw three deported families headed by three women. Two of these families committed the violation of residing in Istanbul even though they had their kimliks issued in a different province. They stayed there without travel permits. Previously, only women involved in criminal cases were deported. Today, women are deported for infractions. [The Turkish authorities] also deported gay asylum seekers.”

The source also spoke about the conditions under which the Syrian refugees are held in removal centers:

“The Turkish authorities are using European and Gulf-funded camps that once hosted Syrian [refugees]. The camps are used to detain people administratively before they are deported. Administrative detention might last up to six months. The long detention periods are accompanied by extremely abusive treatment by the Turkish police [in the camp]. Additionally, the food is of poor quality. People might even find themselves forced to buy food at their own expense while deprived of using phones, not even to hire a lawyer or reassure their families.”

The source added that the Turkish authorities have ordered the crossing’s administration to ban filming at their facilities:

“This came after videos and photos of the deportations went viral. The Turkish authorities do not want deportation videos and photographs to reach the public. Journalists are banned from filming at all border crossings, and entry is denied to TV channels and even to people with cell phones. The Turks allege the ban is because the [Turkish] opposition continues to use photos of people visiting Syria to promote that it is safe and there is no reason why Syrians should not return. Currently, the Military Police has issued bans on filming deportations in bus terminals (where the deported head after passing through the crossing), including in the Sajo Terminal. The ban on filming at terminals, the police patrols claim, is because the journalists often do not have authorizations or are disrespectful to the patrols.”

The source said that some deportees are arrested and detained by the armed groups in control of the area:

“I witnessed the arrest of two people who were deported two months ago by the SNA. One of them was pursued by the Civil Police on criminal charges. The second was charged with being a Syrian regime thug, according to the Military Police claims.”

Notably, the arrests perpetrated against deportees are not limited to the two cases reported by the source. On 5 August 2023, North Press said that the Military Police arrested 15 people as they attempted to cross the M4 Highway into the Autonomous Administration’s areas north of Raqqa. They were arrested two weeks after their deportation from Türkiye. Additionally, the police carried out the arrests in coordination with the Türkiye-backed Ahrar al-Sharqiya armed group.

On 11 June 2023, North Press also reported that the Military Police arrested seven people, among them a woman. Türkiye deported the group through the Ras al-Ayn (Serê Kaniyê) Crossing, north of al-Hasakah. The police took the group to interrogate them without informing them of their charges.

“Departures” under Türkiye’s Orders

The Turkish authorities insist on the “voluntary return” narrative, imposing restrictions even on the terms used by the border crossings to refer to forcibly deported Syrians. In an exclusive account, a source (no. 2) informed of the activities of the Bab al-Salamah Border Crossing said:

“In the beginning, we used the term ‘forced deportation’ on our media platforms. Then, the Turkish authorities directly requested that we not use it and replace it with the term ‘voluntary return’. A while later, we were asked to substitute that term with ‘departure’ from Türkiye. Departure from Türkiye covers multiple categories: forced return, voluntary return, and post-smuggling returns. Today, we report on all three categories under the term departure from Türkiye acting on Türkiye’s request.”

Notably, the crossing aggregates Syrian refugees and asylum seekers into these three categories based on a form they fill out, indicating whether they have “returned voluntarily” or have been forcibly deported and highlighting the presumed reasons for their deportations.

The term ‘departure’ aims to conceal the truth that “the larger percentage was always that of the forcibly deported,” according to the source. He added:

“Since the last week of June, the percentage of forcibly deported people has started to spike. There have been nearly 750 to 800 forced deportations to date, 17 July 2023. As for the daily deportations, the percentage is 30–50–100–150 through the Bab al-Salamah Border Crossing. Over June, there were approximately 1150 departures from Türkiye; 60 percent were forced returns and 40 percent were voluntary.”

About the official measures at the crossing, the source said that after the deportees’ personal information is entered into the crossing’s database, they are granted a paper, effective for 72 hours, stating that they have been deported from Türkiye and that they must not be harassed. The source added:

“We take 50 Turkish Liras (TL) from those forcibly deported; it is the bus fare. The bus takes them to Sajo Terminal, so they would not be at the mercy of private cars. The employees and guards of the crossing do not receive any sums [from the deportees]; this is in line with our general regulations. Any sums taken are in violation of the decisions of the crossing’s administration.”

The source said that the months after the February earthquake witnessed a marked increase in ‘voluntary returns’, pointing out that people returned driven by their compelling financial circumstances. “People lost all their possessions. No one helped them rent a home. Consequently, they returned for a tent,” the source said.

Nevertheless, those willingly returning are only a fraction of the Syrians entering through the crossing, most of whom are forcibly deported. The source said that among the deported are:

“People who do not possess kimliks and people with kimliks but who have committed violations. The violations include lacking travel permits or registered addresses, which causes the freezing of kimliks or an accumulation of unpaid bills. Fewer numbers were involved in criminal cases.”

The source added that among those deported:

“There are old people whose ages fall between 60 and 70 years. There are also children between 15 and 17 years old. The issue with these children is that they do not possess kimliks or proof that they are minors. [These are deported] even though their appearances indicate they are children. The [Turkish authorities] consider them young adults and deport them, taking advantage of the fact that they do not have kimliks to prove the contrary. Over the last three weeks (July 2023), 20 to 25 such children [were deported]. These children belong to unregistered families or are alone, having entered Türkiye to work and support their families in northern Syria, preferring that to joining an armed group. Recently, three families were deported. They told us they were deported because [one of their members was] involved in a criminal case.”

The source highlighted a pattern of deportations whereby the Turkish authorities deport Syrians for alleged crimes, adding that these people are often coerced into “voluntary returns” in removal centers. The source added:

“There is a pattern of deportations whereby a person is captured while involved in a criminal case, for instance. These people are held at one of the camps in Osmaniye, Kilis, Şanlıurfa, or İslahiye in Gaziantep. There, they are treated badly until they choose voluntary return, and their case is closed, even though they are mostly innocent. The cases include instances such as false complaints filed by the Turkish owners of the houses (rented by the refugee).”

In a February 2021 report, STJ documented the arrest and deportation of an Istanbul-based Syrian refugee after his neighbours filed a complaint with the police. Additionally, several other refugees were deported by the Turkish authorities for their alleged violation of Turkish regulations, based on Law No. 6488 of the Law on Foreigners and International Protection Article 54, first preambular paragraph (D), which warrants the deportation of anyone who violates the order of public security.

The source described some of the practices Syrian refugees suffer in the removal centers:

“What is distinct about the recent deportations is [that refugees are subjected to] humiliation through profane language, degradation, and beatings on the face, back, and legs with batons. Additionally, in a very debasing manner, [the police officers] would confiscate the deportees’ belts and shoelaces and cuff their wrists with zip ties as if they had committed a serious crime. Several deportees also told me that their money and cell phones were stolen from storage in the removal centers.”

The source also spoke about the intentional brutality the Turkish authorities are using against asylum seekers attempting to enter through the border:

“In general, anyone who attempts to enter Türkiye through smuggling is immediately taken to the hospital once delivered to us due to the harsh beating they would have suffered if not for a bullet that was deliberately lodged in one of their legs.”

The accounts of the two sources intersect with the testimonies STJ obtained from eight refugees whom the Turkish authorities have illegally uprooted from their lives and returned to a country where they are likely to be in peril.

“Deported with Two Children; They are Not Hers”

On 15 July 2023, the Turkish authorities forcibly deported Roujin (27), a Kurdish woman from Syria’s Afrin city. The authorities relocated her to Syria even though she and her husband obtained kimliks once they entered Türkiye 10 years ago and have remained in the Bitlis province, where their kimliks were issued, since then. She narrated:

“I worked with my husband. We cultivated and harvested tomatoes. We left for work in the morning and returned in the evening. We have four children; they are 12 (sixth grader), 10 (fourth grader), 8 (third grader), and a toddler of two years.”

She added:

“On Friday morning, 14 July 2023, the police showed up. They said they had to search the house and that we had to renew our kimliks because our children have grown up. After the search, they took us to the migration directorate. There, they scanned our fingerprints. My kids and I were photographed. Then, they took us to the hospital for a check-up. They then returned us to the migration directorate, where they interrogated us about the nature of our work and similar details. On Saturday morning, 15 July, they took me and my children to the Tell Abyad Border Crossing and informed us that we were being deported. We asked for the reason. However, they did not respond. I asked them about my husband; they said he was under a travel ban. All my relatives are in Türkiye, and I know no one in Tell Abyad.”

She said that this was not the first time that the Turkish authorities had arrested her husband without a justification:

“My husband is from Afrin too. He remains in Bitlis province, detained at the migration directorate. We have not been involved in disputes with any Turkish citizens in Bitlis. Two years ago, my husband was detained at the immigration directorate for two months without charges.”

Authorities deported two children, ages 15 and 16, along with Roujin. They are her brother-in-law’s children, and she was taking care of them while their parents were away. She narrated:

“Their father was arrested five months ago, and we know nothing about his fate. After the arrest, [their mother’s] health deteriorated, and she was taken to the hospital. She is still there. We brought the children to our home to look after them. They were deported with us. We informed the police that they were not our children, and the police only told me to continue taking care of them. During the father’s arrest, their house was raided and searched. They were taken to the [migration directorate] on the pretext of their need to renew their kimliks. The mother and children were released. The father remained imprisoned at the directorate.”

“Deported because He Left His Kimlik at Home”

On 21 July 2023, the Turkish authorities arrested the Aleppo-born Syrian refugee Mustafa (26) from a street in Istanbul and forcibly deported him to northern Syria, although he had a Kimlik and was staying in his province of registration. He narrated:

“I came to Türkiye in 2015 and obtained an Istanbul-issued kimlik. I sell clothes, am married, and have a child. I left home to fix my wife’s phone. In the same neighborhood, I was stopped by the police and asked for the temporary protection card. I had left it at home because the repairman was in the same neighborhood and very close to the house. I did not expect to encounter a police patrol. I told them the card was at home and that I could go home and fetch it in two minutes, but the police refused and decided to take me to the detention center. I told them I had a child and a wife; they did not budge. I told them I had a photo of the card, but they refused to see it and insisted on arresting me. They said, ‘We will check your status and verify your kimlik at the detention center’.”

However, the police did not subject Mustafa to any identity verification measures at the removal center. He added:

“I went with them. They took me to the Tuzla removal center. They did not scan my fingerprints to confirm if I had a kimlik. Then, they took me to Kilis province. At the detention center in the migration directorate, we were forced to thumbprint sign the voluntary return paper, and our kimliks were deactivated. They refused to hear a word. They sought to arrest any Syrian and get their thumbprint on the voluntary return document [. . .] whether willingly or not.”

On the detention conditions, Mustafa said:

“Treatment in Tuzla is abusive. We were prohibited from raising our heads and asking for water, despite the extreme heat. They offered us water once every seven hours. I spent two days in Tuzla. These were followed by a long journey to Kilis. In Kilis, we spent half a day before we were deported.”

Mustafa is anxious about his family, whom he was forced to leave in Türkiye. He said:

“There is little money left at home. However, I cannot pay the rent. My family is at risk of homelessness if I do not pay the rent. How can I pay while I am without a job and rents are unaffordably high?”

“He Survived the Earthquake but Not Deportation”

The Syrian refugee Hussein had legal residency and a job in Hatay province. However, the February earthquake wreaked havoc on the life he had known in Türkiye since 2015. He narrated:

“I worked as a barber the entire time I was in Türkiye. I had a shop and was known in the area for having never committed a single violation. When the quake hit Hatay, my house collapsed, and all our belongings remained under debris. We lost everything in the quake, including the barbershop, which was my source of income. Today, I have neither a home nor a shop.”

Hussein decided to leave for Mersin to escape Hatay and start working again:

“I arrived in Mersin the second day following the quake. I went to the Mersin migration directorate on the third day to get a kimlik. There, they said, ‘We should bring you in and run a background check.’ Then, they informed me that my name was marked with a restriction code and that I had to be held administratively. This happened on 10 February 2023.”

He added:

“I was held at the migration directorate in Mersin for six days. They made us choose, saying, ‘Do we keep you in administrative detention or deport you to Syria?’ We refused to be deported to Syria, and they took us to Kayseri. There were four taxi drivers with me; they have been working without travel or work permits. Then, I was transferred to a prison in Kayseri. The treatment was terrible. There were beatings, humiliations, and insults. The meals were also poor.”

Hussein’s detention did not end at Kayseri prison, and he was beaten in the next prison:

“I was then relocated to a prison/removal center in Şanlıurfa. There, the treatment was the worst by all measures. Several police officers spoke Arabic; they insulted us in Arabic and Turkish the entire time. Beatings were with batons, with and without a reason. I was held there for three months. You may come across a good officer among a hundred, but the rest are all bad.”

After they held him for a prolonged period, the Turkish authorities deported Hussein to Syria and severed him from his family, who are battling to survive without assistance since the earthquake:

“We were then deported through the Tell Abyad Border Crossing. I have no one in this part of Syria. My family, wife, and two children, a girl (12) and a boy (14), remain in Türkiye without a breadwinner. I could not rent a house for my family. I left them with acquaintances. They are staying in Mersin. Right now, I am not sure about their status or whether they are at risk of deportation.”

As for the reason behind his deportation, Hussein said:

“Four months into detention, my family hired a lawyer. He said the reason I received a code was because my name came up during an inquiry into allegations that I had bought stolen goods. Throughout my administrative detention, the [authorities] never once questioned me regarding the crime I was falsely accused of or the stolen items I purportedly purchased.”

“He Never Knew for What Violation He was Deported”

Sami (34), an Aleppo-born Syrian refugee, had a legal residence in Istanbul since 2013. However, all the official documents he possessed failed to protect him from forced deportation to Syria. He narrates:

“In 2015, I opened a mobile phone shop after switching jobs several times. I licensed the shop and established a small company. I also obtained a work permit and health insurance. My shop is in Esenyurt.”

He added:

“During this [deportation] campaign, in early July, the police visited the shop and asked to check all the documents and accounting records. They first objected to a word on the shop’s sign. I had written my name in tiny Arabic letters. I told them this was legal. They said, ‘We used to allow languages other than Turkish 15 percent of [the writing space on the sign]. Now, this is prohibited.’ I asked, ‘Is this an official decision? No one seems to be aware of it?’ They silenced me and scratched [my] name with a knife. Then, they said there were issues with the accounting records. I called the accountant. He told me, ‘They want to fine you, one way or another. Therefore, do not argue with them.’ Then, they searched the shop and discovered non-Turkish used phones that I sold. [The police officer] said this constitutes a violation because there are no invoices on these sales. They began searching for reasons to fine me.”

Sami showed the officers his official documents, but they ignored them and insisted they could not verify his status without a fingerprint-based background check. Additionally, they refused to inform his lawyer of the destination to which they were taking him. Sami added:

“I closed the shop and accompanied them. I was shocked because they took me to Tuzla. They withheld my phone, and I could not tell my lawyer where I was. Two days later, I underwent a fingerprint scan. The employee said nothing, and I expected they would release me because my documents were all regular. We were left in the sun the entire time. There were massive numbers of people—nearly 1500—of all nationalities. However, the larger percentage was Syrian. There were even tourists from the Gulf region. Their documents had been stolen, and they attempted to show the authorities the [digital copies] they had on their phones, but the authorities refused to check them. Tuzla is the epitome of xenophobia and the ill-treatment of Arabs. The police officers carried batons all the time, and if someone dared to protest at anything, they hit them randomly. They did not seem to have a problem with where the baton landed, whether on the head or the back. The food was meager. It consisted of a glass of water, half a loaf of bread, and a small piece of cheese.”

The officer at the removal center told the detainees that they would be relocated to a police station in preparation for their release. However, what awaited them was yet another removal center:

“Following the fingerprint scan, they brought buses. They tied our wrists and made us board the buses. The ties were black plastic cuffs. They said, ‘We will take you to the police station and release you from there.’ They said that to calm us so we would not cause trouble during the deportation. The buses headed to Şanlıurfa. Then, another lie followed. [The officers said] that according to the interior ministry’s instructions, our fingerprints must be scanned at the migration directorate in Şanlıurfa as a punishment for us before we are released. Their deceit was blatant. However, the detainees had no other choice but to believe them. Sixteen hours later, we arrived in Şanlıurfa, and they made us get off at the Harran Camp. Two days later, they scanned our fingerprints and said they would release us tomorrow. The next morning, around 5 a.m., they got us in the buses and took us to Tell Abyad crossing. [After we got off], they gave us our personal belongings. People were genuinely shocked. Some have lost money, others their phones. When we protested, the police officers said they had nothing to do with it and that it may have occurred in Tuzla. They pulled out their firearms and threatened us when we disputed their claims.”

Sami also spoke about his experiences on the other side of the border:

“We walked towards the Syrian borders. The Syrian crossing registered our names, birthplaces, and some details about us and let us go. [The deportees] have no one in Tell Abyad. The mosques were bursting with people. We decided to sleep on the street. Two hours later, fighters [from the Liberation and Building Movement] approached us. They offered to smuggle us into Jarabulus for 600 USD. A few people accepted, paid the money, and went with them. Two days later, we called them. They told us they had arrived, having passed through the Kurdish-held areas in Manbij. A while later, the local council in Tell Abyad started an initiative because the streets and the mosques were overwhelmed with deportees. Turkish buses came. The [Turkish police] handcuffed several people and transported them to Aleppo’s northern countryside. They were doing the people a favor after they had created the problem.”

Sami describes what happened as an “attempt at robbing him” because the quick deportation measures did not give him a chance to address the violations he allegedly committed:

“I reached out to the lawyer. He told me that he went to Tuzla and that they did not allow him to see me. He also said he could not start the legal proceedings because the deportation was quick. Now, I am facing a massive challenge. I had deposited nearly two million Turkish liras in the bank. When my kimlik stopped, they froze my bank account. I also have a car and a small apartment registered as property under the company. I have no idea what will happen to these. For the time being, the lawyer has asked for a huge sum of money to start legal action. I do not want to return to Türkiye, but I want the money in the bank. I wish to sell the car and the apartment and travel to Erbil, where I can apply for a visa in some country and start working as a merchant there.”

Sami added:

“I still do not get why they deported me; if it were due to business violations, I would have simply paid the fine the next day.”

In 2023, several Turkish municipalities, including the Esenyurt Municipality in Istanbul, started to take down shop signs displaying Arabic writing. They are enforcing a law that, though it had existed previously, was not implemented. The law stipulates that “75 percent of words on any sign be in Turkish and the Latin alphabet.” The law also bans signs in languages other than Turkish, including Arabic and English, among others.” However, so far, the application of the law has remained bound by the “whims of municipality directors.”

“Deportation Denied Him a Life-saving Surgery”

In 2022, Mousa entered Türkiye after he had a heart attack. The migration directorate issued him a kimlik because he needed long-term medical care due to his severe health issues. He was scheduled for surgery on 10 August 2023. However, he was arrested, detained, beaten, and deported to Syria before the time came. He narrated:

“Three months after I came to Türkiye and obtained a kimlik, my wife was smuggled into the country. We had two children: a little girl, 2 years old, and a little boy, 7 months old. I constantly tried to obtain kimliks for my wife and children but could not. [. . .] most of the provinces were closed [to Syrians].”

Without official documents, Mousa’s wife and children were vulnerable to arrest by the Turkish authorities:

“My wife went to buy medicine for the child. The police stopped her at the pharmacy’s door. Because she did not have a kimlik, [they arrested her] and my youngest child for seven days. The child was sick. When I went to [the police] to ask them to only take them to the hospital because they were ill, they started calling me names and threatened to deport her. The day my wife was arrested, the police came to our house and took all the documents I had, even the baby’s birth certificate. They left [me] no identification documents.”

Mousa posted a video speaking about what had happened to his wife and child. After the video, the police released his wife but arrested him on 30 November 2022:

“[After I posted the video], the police started patrolling my street. They would stop across from my house for an hour before they left. This was suspicious. Later, I went to buy stuff from the shop. They went in and kidnapped me. I was held in a prison affiliated with the migration directorate in Hatay. Three days later, they told me I would be administratively detained for six months. We remained in the same place until the earthquake. The building collapsed while we were still inside it. Up to that point, I had been [in detention] for three months.”

The Turkish authorities transferred Mousa to several detention centers following the quake. He was denied necessary treatment during his detention and was ultimately deported to Syria through the Tell Abyad Border Crossing:

“The day the quake hit, on 6 February 2023, we were relocated to the officer’s camp near Antakya. On 10 February, we were transported to Kayseri prison, where we were held for two months. In Kaysari, the treatment was extremely terrible. There were beatings with batons. [We were] hit just for being Syrians. The food was inadequate. On 7 April, they took us to Şanlıurfa prison, where we were subjected to the worst treatment ever. This applied to food, beatings, humiliations, and insults. In the Şanlıurfa prison, my health deteriorated repeatedly. They took me to the hospital only once, and they refused to do so on other days. On 14 July, we were deported through the Tell Abyad crossing.”

Mousa said that the Turkish authorities deported him even though Ankara had already issued his release order on the same day he was forcibly returned to Syria:

“They did not ask us which crossing we preferred; we found ourselves at the Tell Abyad crossing. I was deported in a batch of 127 people. Most of us had no place to sleep or go to—neither relatives nor friends. We all sleep in the mosque after 12 p.m.”

Mousa’s wife and children, who are at risk of deportation, remained in Hatay without any money to keep them afloat, while he decided to work on farmland in an attempt to provide for them despite his critical health condition.

“He Underwent 16 Background Checks”

On 4 June 2023, the Turkish authorities deported Damascus-born Ahmad, careless of his serious health issues. Ahmad was deported because he could not renew his residence permit. He narrated:

“I entered Türkiye in 2018 and remained without identity documents for a year. Later, I obtained a document from the Turkish Red Crescent stating that I was being treated for a bacterial blood infection. I submitted the document to the governor’s [office], petitioning them to issue me a kimlik or residence permit. The governor approved granting me a residence permit for treatment purposes. I also obtained a work permit and health insurance from the concerned departments in Istanbul. All my papers were regular. Because of the nine-day Eid holiday, reservations, and appointments, I was exactly 21 days late for renewing my residence permit.”

A police officer in plainclothes approached Ahmad in the Fateh area of Istanbul, where he had lived for six years and had a registered address. Ahmad showed the officer his official documents, but he was not content. He asked Ahmad to accompany him to the car to verify his legal status. Ahmad added:

“He wanted to do a criminal background check in the car. Before that, he asked me, ‘Are you sick?’ I told him about my illness and treatment with the Red Crescent. Then, he asked me, ‘Why did you miss the residency renewal?’ I told him about the Eid holiday. He insisted that I go to the car. They took me to Aksaray, where they ran a general security check. [The officer] wanted to perform the background check again in Tuzla. I refused. The officer demanded that I shut up and told me I had an irregular status.”

Ahmad says that the officer should have considered his serious health conditions, especially that he was vulnerable to developing cancer should the bacteria levels in his blood increase, based on the Red Crescent’s evaluation of his case. However, the police relocated him to the Tuzla removal center:

“In Tuzla, a caravan was running checks on the people there. There were four people with me. We all had legal status. One of the men had an Istanbul-issued residence permit, and two had Istanbul-issued kimliks. [The police] claimed they had an irregular status as well. In the caravan, the police employees said, ‘These four are clear’. However, the same officer [who arrested me] asked for another security check on our names. We protested and told him that we wanted to make a call and hire a lawyer. He started calling us names and insulting us. He insisted on the checks. By then, I had been subjected to three background checks, even though I had not missed paying a single bill. A gendarme came in to see what was happening, while another started hitting me with a baton. They took me to the [center’s yard]. Then, they brought me before the detective. I told him my status was regular and I had only committed this violation. I also said I could easily address it by booking an appointment after Eid ends.”

Ahmad said that he was subjected to “16 background checks since he was arrested and up to his deportation”, further describing the conditions in the Tuzla removal center:

“In Tuzla, you cannot call on the police officer. If you do, you will be hit with batons. The police officers were extremely repressive. Additionally, there was a ban on smoking, drinking water, and using the toilets. The numbers [of detainees] were horrifying. They were from all nationalities, but the majority were Syrian. There was a lot of garbage and a lack of hygiene. They offered us a small loaf of bread, a jam can, about one spoon, a small juice box, and a glass of water throughout the day. They offered us the same meal the next day. Beatings in Tuzla are reserved for Syrians. People of other nationalities were never hit; only Syrians were. The beating was exclusive to Syrians and with batons. The police officers carry batons all the time. If you passed by an officer, he would hit you for no reason.”

Ahmad was relocated to the Şanlıurfa Camp/Haran camp. There, he was imprisoned, extremely beaten, and coerced to sign the “voluntary return” paper. He added:

“We were then deported to the Şanlıurfa camp (a school with tents in Şanlıurfa’s suburbs). They scanned our fingerprints. After I argued with them, they beat me with batons so extensively that I felt my back was broken. They then took me to a cell. Shortly after, they took me out to thumbprint the voluntary return paper. I asked them, ‘Where to?’ They said, ‘Tell Abyad.’ I argued with them again because I had no one there. They returned me to a cell, where they held 42 people. In the cell next to us, there were 37 people. In the [third cell in the line], there were 22 people.”

Ahmad refused to be deported to Tell Abyad because his entire family in Syria resides in the Syrian government-held areas. All those detained with Ahmad in the camp shared his objection to the destination:

“The [detainees] in the three cells mutinied because the majority are from Idlib and wanted to be deported through Bab al-Hawa crossing, as none of them had relatives in Tell Abyad. [The authorities] tried to force me into fingerprinting the voluntary return paper, with the destination being Tell Abyad again. I refused. They hit me with batons again. On the third attempt, the authorities made us thumbprint the papers to be supposedly deported to Bab al-Hawa. On the first day, they brought buses headed to Tell Abyad. We refused to board them. They repeated the process for the next three days. The buses they brought had the Turkish Red Crescent logo. All the deportee batches that preceded ours were taken to Tell Abyad, as were a few groups that followed us. On the fifth day, they brought buses bound for Bab al-Hawa. However, before we got on the buses, a high-ranking officer came and started humiliating us. He slapped us on our faces and showered us with profanity.”

The deportation buses took Ahmad’s batch to the Bab al-Salamah crossing, not to Bab al-Hawa, contrary to what they chose. Additionally, as in several of the cases reported above, Ahmad also lost some of his personal belongings, including the cash he had, his phone, and medications—cortisol tablets, which he receives every three months and cost him 2450 TL. Ahmad said:

“I had lost them in Tuzla. I asked for my medications in Tuzla, and the [police officer] refused to hand them over. He stepped on them. This happened when I gave them my possessions for storage, even though I had notified them that the reason behind my illness, my infection, was detention by the Syrian government.”

“They Hastily Deported Us before our Files were Processed”

On 14 June 2023, the Turkish authorities deported Aleppo-born Ziyad (27) because he sought medical treatment in Istanbul without a travel permit while having a Bursa-issued kimlik. He narrated:

“I came to Türkiye in 2017 and worked as a blacksmith in Bursa. I had a kidney injury and went to a hospital in Bursa. I went to the emergency room to stop the bleeding. I then went to Kayseri in search of a doctor [capable of treating my case] and did not find one. The people told me to visit Istanbul because it had many doctors. I traveled there.”

He added:

“When I arrived in Istanbul, the campaign had already started. [The police] stopped me at Esenyurt Square and asked for my kimlik. Seeing that it was Bursa-issued, they asked for the travel permit. I told them I did not get one and that I came for medical treatment. They ordered me to accompany them, intending to run a security check on my background. I slept at the Esenyurt Police Station. Later, they transferred me to Tuzla, then to Şanlıurfa Camp.”

The detention periods and conditions varied in the three centers where Ziyad was held. He added:

“At the Esenyurt Police Station, I was held for four days. The treatment was fine, and they offered me three meals a day. They then relocated me to Tuzla, where I spent 18 days. The treatment was terrible. I asked for medications several times in Tuzla, but the [authorities there] refused. I showed them I had a kidney injury. However, they did not react, even though I was in excruciating pain. In Şanlıurfa, the treatment was abusive. I remained there for four months. They told us this was administrative detention and that a few of us would be out before Eid. However, we were unsure what being out meant—whether it was release or deportation. We were deported through the Tell Abyad crossing, and I truly have no one in Tell Abyad.”

In Şanlıurfa Camp, Ziyad pinned his hope on an UN-affiliated law office, which helped refugees at risk of deportation:

“In Şanlıurfa camp, people exchanged the number of a law office, saying they helped refugees threatened with deportation. Indeed, I shared the number with my family when they visited me. My wife called them. They took my personal information and reviewed the medical reports. The lawyer showed up the next day. He was accompanied by an interpreter. He told me, ‘Your status is regular, and you have health issues. However, you have committed a violation. I will file for a release order because you are not involved in a crime, while you also have a kimlik, etc.’ Several other people hired the lawyer, and he filed for release orders on their behalf. Many were indeed being released. However, the camp’s administration hastened our deportations before our files were processed.”

Like the multiple Syrian families torn apart by forced deportations, Ziyad’s wife and son were separated from him. They remain at his in-laws without support because the deportation robbed Ziyad of his job.

Notably, in 2019, the Turkish authorities obliged Syrians holding “temporary protection” status to obtain travel permits, banning them from moving between the Turkish provinces without authorization and threatening violators with cancelling their kimliks. The law was publicized in a statement titled “Important Warning.” To get the permit, Syrian refugees had to file applications in person with the migration directorate or other departments specified by the provinces.

Later, the authorities facilitated access to the authorization by providing the service online, despite the fact that obtaining permits remained difficult and bound by several conditions. The conditions included that applicants upload proof of their reasons for visiting the destination area, knowing that proof does not guarantee the applicant will be granted the permit.

“As If Held in the Saydnaya Prison”

On 15 August 2023, the Turkish authorities deported Daraa-born refugee Abbas (33). He entered Türkiye in early 2019 and attempted to obtain a kimlik through legal and illegal channels by resorting to brokers. However, he failed because most Turkish provinces had stopped registering newly arrived Syrian asylum seekers by then. Abbas narrated:

“I was out of the house buying some stuff. A plainclothes police officer stopped me and asked for my kimlik. I told him I did not have one and gave him an expired Syrian passport. Once he saw the passport, he told me to go to the car immediately. I [. . .] tried to invoke his mercy by saying that I had a family and I was their provider, in Turkish, of course. He refused to listen. They drove in the area for nearly two hours, and while speaking to each other, [one officer] said, ‘This guy looks Syrian; get off and ask for his kimlik.’ I mean, the police were literally not looking for irregular migrants; they were just looking for Syrians. They took me to Bağlar Detention Center. I was searched and exposed to gross insults. They took everything from me, put the items in a storage bag, and photographed them. They took me down to a cell. We were nearly 72 people in a 4-by-5-meter room. They sat as if in Saydnaya prison—’one leg extended, the other folded, touching the chest.’ There were 17 Syrians and eight Afghans.”

Abbas and others detained at the center were denied medication, drinking water, using bathrooms, and even talking, and if they made a sound, police officers would beat and insult them. The police had arrested detainees from various places, including their homes and workplaces. However, Abbas says they missed their time at Bağlar when they were transferred to Tuzla:

“At night, they assembled all the detainees. We were 72 people on a bus that only accommodated about 55 people; they put us on top of each other and in the corridor; they treated us like cattle. They then took us to the Tuzla detention center. The numbers there were horrifying. They rounded up [new] people every three or four days. And there, they performed background checks. They scan your fingerprints and check your status, having access to everything from your kimlik to your bills and health conditions. They put us in an open square under the sun. The night was cold. We were left without food or water and were denied access to toilets. We were not allowed to make any noise, all of which was accompanied by insults and profane language. [. . .] If someone tried to ask for water, toilets, or medicine, the police would gang upon him and beat him severely, with hands, legs, and batons.”

Abbas said that these procedures are enforced before the fingerprint scans. After the scans, if the decision is deportation, the police would take the detainee to a cell, tie his hands with plastic cuffs, and offer him food for the first time. Abbas had his first “expired” meal three days after he was brought to Tuzla. On that day, he was transferred to Kilis:

“The buses came in. They led us to the buses […] and started tricking us. They said, ‘We are taking you to issue you new kimliks and settle your legal status.’ Those present could not help but feel optimistic. However, this move was meant to control us. We stayed tied up, and whoever talked or asked for something they pulled the plastic cuffs on their wrists. We remained like this for 17 hours, from Istanbul to Kilis. They took us to the hospital while the cuffs were still on our wrists, just like when they brought a prisoner to a hospital to treat him. From afar, the doctor looked at us and stamped our papers without examining our health. They took us to a camp across from Kilis city. They put papers in front of us and made us thumbprint them without saying anything. They threatened, insulted, and ganged up on those who refused to do so. It was a voluntary return by coercion. In Kilis, we stayed for a day and a half and had been [detained] for two and a half days before. All we wanted was for this to end. We wanted to inform our families of our whereabouts. They showed us no mercy, and even a short phone call was forbidden.”

The Turkish authorities took Abbas and the others with him to the Bab al-Salamah crossing without asking them for their preferred route. After the authorities gave them their belongings back and photographed them, the deportees walked about 50 meters to the Syrian side of the crossing. On the Syrian side, the suffering of the deportees took another form:

“As soon as we arrived on the Syrian side of the Kilis crossing, the faction in control demanded 200 TL, and the payment was compulsory. They gave us a paper effective for 72 hours based on which we could navigate the area, and it was useless. We got out of the crossing. The Military Police picked us up immediately. [The police] started interrogating us as if we were terrorists. They carried out a thorough search of the mobile phones and recovered all the old information. They violate the privacy of your conversations and pictures of your family while asking terrible questions. Even the [Syrian] regime does not ask all these questions. [After the police], next comes a security office in A’zaz terminal, where you are searched and subjected to a security check. In the end, they ask you to pay them money. Then, there is the Kafr Janneh checkpoint, which carries out a photo-based security check. Your photo is shared to a [WhatsApp] group, and you are arrested if you are suspected by the security group. They subject you to searches and checks so that they would ultimately ask for money. The factions do not give receipts. After payment and checks, they tell you they can get you into Türkiye by smuggling.”

Abbas said his group was deported in three batches, including 32, 32, and 36, totaling 100 people. These entered the crossing within an hour and a half. He added that on the day he was deported, he witnessed the deportation of three groups, making the total number of deportees 300.

Is the Destination Safe?

The three border crossings used by Turkish authorities to forcibly deport Syrians lead to three areas in northern Syria. The Bab al-Hawa crossing opens to Idlib province, which is entirely controlled by the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS).

Bab al-Salamah leads to A’zaz city in northern Aleppo, which is predominated by the Türkiye -backed SNA.

Tell Abyad provides a gateway towards Tell Abyad city, which Türkiye controlled in the aftermath of the 2019 Operation Peace Spring.

Notably, the ongoing deportation campaign is propelled by the “voluntary return” project, which Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan announced on 3 May 2022 while declaring the start of the brick houses project. With these houses, Erdoğan intends to accommodate one million Syrian refugees.

In a 25 May 2023 speech, Erdoğan confirmed that the housing project is underway with Qatari funding, adding that “with this project we begin to establish infrastructure for Syrians’ voluntary return” to northern Syria.

On 24 May 2023, the then-Turkish interior minister, Süleyman Soylu, attended the ingurgitation of the housing complex planned in Aleppo’s northern countryside. During the event, he said, “Syrian refugees living in Türkiye will settle in these homes as part of their voluntary return. [. . .] There is a serious demand for the return to this safe area.”

However, reports from several rights organizations refute the Turkish claims of “safety” in northern Syria, documenting how shelling in Idlib and Aleppo’s northern suburbs continues unabated. In an August 2023 report, STJ recorded 10 Russian airstrikes in Idlib and Aleppo. The attacks killed nearly 36 people and wounded 88 others, mostly civilians, between 2021 and 2023.

Moreover, the testimonies STJ collected for this report show that Turkish authorities are sending the larger portion of forcibly deported Syrians to Tell Abyad against their will. The majority have no relatives to rely on for survival during their coercive stay in the city, which lacks life-affirming resources, while also condemned to geographical isolation. Tell Abyad is a locked enclave disconnected from the rest of the Türkiye-controlled areas in northern Syria.

Notably, the situation in the city ultimately forced the Turkish authorities to transfer dozens of deportees from Tell Abyad to A’zaz, passing through the Turkish territories, after numerous videos surfaced that shed light on their poor living conditions.

Like Idlib and northern Aleppo, Tell Abyad remains unsafe according to numerous reports by rights organizations. In a June 2023 report, STJ captured the situation in the area through the testimonies of 62 victims, who were tortured and ill-treated by the Türkiye-backed SNA factions in Tell Abyad and Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê.

The Rise of Anti-Syrian Sentiment