-

Executive Summary

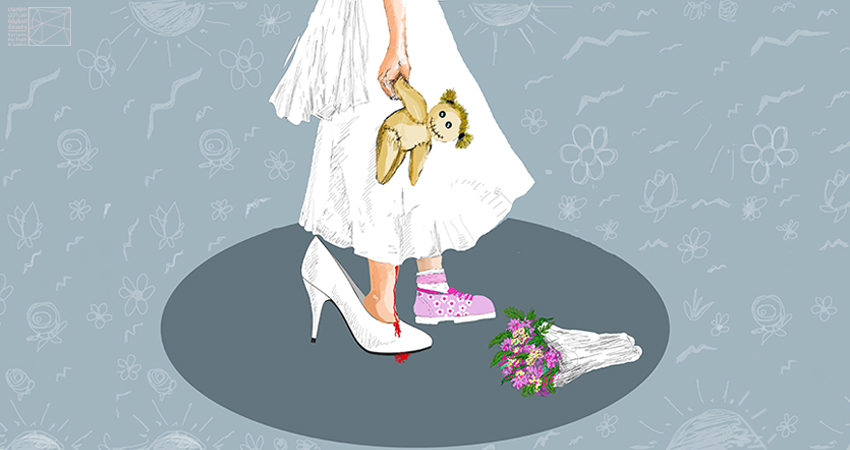

The Syrian conflict, which has been going on for more than nine years, induced a tragedy, with consequences that will definitely continue to haunt countless women, particularly adolescent girls, who persistently grabble with complex challenges, sufficient to change the course of their growth and life permanently. Perhaps, early marriage / child marriage is one of these challenges,[1] for despite being an old phenomenon in Syrian communities, child marriage cases have been ascending an upward trajectory with the escalation of the conflict.

In this extensive report, Syrians for Truth and Justice / STJ brings under the spotlight the difficulties adolescent girls battle with throughout Syria, particularly in Idlib province,[2] and northern rural Aleppo,[3] as well as al-Hasaka province, held by the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria. The difficulties are actually the result of giving girls in marriage at an early age or persuading them into believing that marriage is the only solution to conquer their social isolation. Monitoring the past three years of the Syrian conflict, STJ recorded a marked increase in early marriage cases. In Idlib, for instance, early marriage ratios exceeded other marriages in the province. The same surge was detected in northern rural Aleppo.

In al-Hasaka province, northeast Syria, SARA Organization for Combating Violence against Women documented 82 child marriage cases between 2019 and the first-half of 2020.

In this report, STJ recounts the stories of Syrian girls forced into early marriages in different years over the course of the Syrian conflict. A number of these women were subjected to violence and abuse at the hands of their husbands. Others, however, had to survive the risks of recurrent miscarriages. In a third group, women were divorced and turned into a target for social critique and the oppression of their surrounding communities; they have even become mothers and breadwinners regardless of their young age, struggling for their lives despite all the hurdles.

Information obtained by STJ indicates that poverty and displacement, as well as established traditions and norms are the reasons, which, in one way or another, increased early marriage cases in the target areas, particularly among the displaced, being marginalized and the most vulnerable groups.

Furthermore, the report details the adverse effects of early marriage on girls, including depriving them of choosing their life partners in most cases, and the direct threat such marriages have on the girls’ health, given pregnancy complications and delivery at a later stage, in addition to a mounting number of divorces, which is an absolute out-turn for an indefinite number of marriages, since several couples are incapable of comprehending marriage as an institution due to their young age.

It appears that the most dangerous of these consequences is that these marriages are not officially registered, especially in Idlib province and northern rural Aleppo, which are held by armed opposition groups. Having kept a track of several early marriage cases, it became clear that these marriages are registered neither at the local courts in both areas, since the courts lack official recognition, nor at the courts in areas held by the Syrian government, for numerous families refrain from seeking courts there, fearing arrest. This lack of official proceedings leads to serious consequences, especially for the wife and children, including primarily the wife’s denial of the registration’s recognition and carrying out the children’s affiliation proceedings, and depriving her of her rights to inheritance or obtaining her marital dues (in advance/ deferred dowry), if a dispute arises. Regarding children, the consequences are also drastic, for they might grow to be almost stateless, because the unregistered marriage denies them birth certificates and other official documents, which in turn, deprives them of their entitlements to education, job opportunities, inheritance, and having a family.

In a report published on March 2019, entitled “When caged birds sing: stories of Syrian adolescent girls”, the United Nations Population Fund (UNPFA),[4] stated that 12% of registered marriages among Syrians involved girls under age 18 when the Syria crisis erupted in 2011. This figure rose to 18% in 2012, and to 25% in 2013. In early 2014, the figure had reached 32% and has remained relatively constant since. The figures, included in the report, match the ones local sources and women activists provided to STJ.

On the same note, Widad Babiker, UNPFA Program against Gender-Based Violence official, made a statement to the Syrian al-Watan Newspaper in March 2019, saying that, in Syria, early marriage rates rose from 13% to 46% over the course of the war, stressing that the rates surged again after they dwindled before the conflict. The figures are reported according to studies conducted by the fund in several Syrian areas, she added.[5]

-

Methodology

In terms of methodology, the report is based on a total of 18 interviews and testimonies. STJ’s field researchers interviewed 11 adolescent girls, given in marriage at an early age, some of whom were coerced into the relationship at various intervals during the Syrian conflict in Idlib province, northern rural Aleppo, and al-Hasaka province in northeast Syria. Moreover, the researchers documented three testimonies, provided by relatives of girls who also suffered due to early marriage.

Along the same lines, an Idlib-based women rights activist provided an account, addressing the rising ratios of child marriage in Idlib province in the past three years. Commenting on the situation in northern rural Aleppo, an informed source reported that early marriages constitute 60% of the total marriages in the area.

Added to these tow accounts is the testimony provided by Arzo Tammo, the Pattered Women Affairs Committee official, under the SARA Organization for Combating Violence against Women in al-Hasaka province, northeast Syria.

Moreover, another interview was conducted with an Idlib-based judge, who explored the consequences of child marriage, and the negative impact it has on the Syrian society as a whole, and on wives and children in particular.

The majority of these interviews were conducted between early 2020 and mid-July of the same year. A number of witnesses were met in person. Others, however, were interviewed online. Additionally, numerous open sources were consulted, information cross-referenced, and further evidence of the cases documented by the report was obtained. It is important to mention that STJ provided the girl witnesses with pseudonyms, given the sensitive nature of the report’s subject matter.

-

Displacement and poverty leading reasons why child marriage prevails in Idlib

Child marriage is deeply rooted in Syrian communities. But still, STJ monitored a marked increase in these marriages as the conflict in Syria grew more acute, particularly in areas outside the control of the Syrian government in Idlib province, where poverty plays a central role in the growth of this phenomenon, especially among the internally displaced groups. Fathers, heads of displaced families mostly, seek to give their daughters in marriage to escape economic burdens, prompted to do so by the repeated displacement from their home areas during confrontations.

Furthermore, traditions and customs which dominate the Syrian society are also of the key reasons to the spread of early marriage in Idlib province, including intra-family customs, among second and third degree relatives, where customs ordain that an adolescent girl has only to be someone’s paternal or maternal cousin to be given in marriage to one of the extended family’s men. There is also the social legacy, namely norms related to keeping the family line and multiplying the number of a family or a clan’s member. In the second case, girls are not granted the space or the chance to contemplate marriage or choose a life partner. Another major factor that is helping early marriage cases increase is education, for the war in Syria has prevented numerous children from pursuing education, with several reasons denying them access to schooling, such as the rampant security conditions, constant displacement of the population, and customs and traditions which deprive girls from their right to education.

In Idlib province, cases of early marriage are also on the rise due to lacking efforts aimed at raising awareness or discussing matters viewed as out of the scope of the society’s traditions and customs, for girls below the legal marriageable age are not provided advice on or cautioned against the risks posed by early marriage.

a. “My family chastised me every time I complained”

Born in the al-Van village, eastern rural Hama and displaced to Dair Hassan Camps in northern Idlib, Manal M. was coerced into marriage when yet 15 years old. She was given in marriage to her 18 years old paternal cousin due to repeated displacement and her family’s tight finances. Later on, Manal was subjected to violence and pattered by her husband because she was unable to get pregnant. She said:

“In mid-2015, my father decided that I must marry my paternal cousin, for we were constantly on a flight of displacement, forced out of the towns we were already displaced to. The marriage ritual was carried out by a sheikh and was not registered at specialized courts. My husband then tried to obtain a family document from the camp where we lived —namely Dair Hassan. My life was everything but happy, especially in the first months into the marriage. I was continuously beaten by my husband, who could not maintain his nerves being young himself. When I complained to my family, they chastised me and cautioned me against speaking about my life to anyone. My mother always had one thing to say: ‘your life will get better after you give him a child.’ Today, several years later, I failed to get pregnant, and my mother keeps taking me to doctors to find the problem. But all her efforts were to no avail.”

b. “Her husband was killed. She is still fighting to survive and raise her little girl”

From the village of Eblin, Mount Zawiya in Idlib province, Rahaf M. also recounted her story. She is another adolescent girl given in marriage at an early age. She was 16 when she married a relative, who was 17 years old. In 2018, in the presence of witnesses and a sheikh, the marriage ceremony was held, but the marriage was not registered at Idlib’s courts, which armed opposition groups control, neither at the Syrian government ruled areas, fearing arrest and mandatory conscription, recounted Rahaf’s relative. He added:

“Rahaf was out of school due to war. Accordingly, her family gave her in marriage to a relative, for the family traditions necessitate that girls marry once they are done with elementary education. However, a year and a half into their marriage, Rahaf’s husband was killed in one of the military operations in Idlib, after she gave birth to a girl. All of a sudden, Rahaf was left to face challenging living conditions, especially since she was ignorant of the means needed to manage her life, while also unable to work to make a living for her child and herself. Rahaf is still fighting to survive and raise her little girl after her husband died.”

c. “Driven out of marriagehood, she returned as a child woman”

Layan A., from Ma`arat al-Nu`man, Idlib, and displaced to the Qah camp area, north of Idlib, is another adolescent girl cast into the world of early marriage. In 2018, Layan, back then 14, was coerced into marrying her paternal cousin, who was 22 years old. Shortly after the marriage, Layan’s husband disappeared, until she was informed that he decided to seek Europe, taking the smuggling routes, and that he did not want to stay married to her. She was thus abandoned to be a target for her surrounding community’s criticism and oppression. She returned to her family’s tent, carrying a newborn in her arms, a source close to Layan said. She added:

“Layan A. born in 2004, was a child when coerced into marriagehood, which cast her out and returned her as a child woman. Layan spent her early childhood in Ma`arat al-Nu`man. Once 10 years old, she left in the company of her family to the Qah camps, north of Idlib. There, she grow up. Given the camp life and the difficulties it gives rise to, Layan did not enjoy her right into childhood or fun, which were limited to playing inside a tent that could not protect her delicate body from neither the cold, nor hot weather. When she turned 14, her father decided to give her in marriage to her 22 years old cousin. Five months into their marriage, Layan got pregnant despite her skinny body, which struggled in a whirlpool of pregnancy-related illnesses and pains.”

In early 2019, the witness added, Layan’s husband got missing, he simply disappeared. The family searched for him at hospitals and security posts, but to no use. Soon, Layan’s mother-in-law located her son, and informed her that he arrived in Greece and is traveling to Europe. This was not a news to Layan, who thought that her husband will apply for reunion proceedings, to bring in his wife and yet to be born son. However, Layan was shocked when her husband sent her father a text message, saying:

“I did not wish to marry your daughter. I was not even contemplating marriage due to my poor economic conditions. Forgive me. I cannot live in a tent any more. Please, take care of Layan and her son.”

The witness added:

“All Layan could see was darkness. Her chief concern was raising her son, who will be covering his needs? Is it the father, or will her in-laws take him from her? She, thus, returned to her family’s tent. But she returned as a mother this time, toys and playing around, her interests about a year ago, were out of question. She was transformed into a woman, shamed by her surrounding community and observed by men’s prying eyes as an object of desire, an attitude that results from a bleak mentality, that married women are always lustful for sex. Today, a year after giving birth, when yet at the age of 16, Layan has become a mother, forced to work in the fields for a daily wage of 1000 Syrian Pounds, just to feed her son and meet his needs. Since he sent the text message, nothing was heard from the husband, who did not attempt any contact with Layan, or her father.”

d. I was coerced into early marriage for “reproductive purposes”

From rural Idlib, Nariman N. is a third victim. She was wed when yet 16 years old for reproductive purposes—that is preserving the extended family’s linage, according to a relative. He said:

“Nariman’s parents agreed to marry her to an 18 years old man, seeking to preserve the extended family’s lineage. She was not the only girl given in marriage for this purpose in the region, for most of the families there tend to marry their daughters at an early age. Numerous adolescent girls are engaged when yet 13 years old, and are wedded one or two years later, waiting for them to be fully matured girls. Concerning education, the majority of the families refuse that their daughters pursue an education after elementary school. Moreover, most of the area’s couples did not register their marriage at concerned courts, for husbands fear arrest at the government checkpoints and being recruited to perform military service. Almost all families refuse to send their daughters to areas controlled by government forces, worried that they might be arrested or insulted by the checkpoints’ personnel.”

The witness added:

“Some families seek to obtain a family book from government directorates in the Syrian government control areas, helped by brokers and persons who manage such proceedings. Nevertheless, such documents usually cost people about 10,000 Syrian pounds. Husbands who cannot afford the cost, thus, register the marriage at and obtain a family book from courts and directorates affiliated with the factions of the armed opposition, particularly Hayat Tahrir al-Sham / HTS.”

-

Early marriage in northern rural Aleppo

Areas in northern rural Aleppo also witnessed an increase in early marriage cases, among girls under the age of 18. There, the spread of the phenomenon is attributed to reasons matching to the ones led to the rise in child marriage among IDPs in Idlib province.

a. “The relationship was difficult and turbulent, to the extent that my husband dared to hit me”

Displaced to Rajo village in Afrin, Alaa K., from Hama city, is another victim to beating and domestic violence. She was constantly pattered by her husband, after they wedded when she was only 16 years old. In 2017, a sheikh proceeded with the ritual, but the marriage remained unregistered in courts. Alaa recounted the following:

“There was not a principal reason for giving me into marriage while still at that age, except for the fact that the young man (22) proposed. I agreed, as I merely did not want to miss the chance, especially since all my sisters were already married. I was not provided with needed or otherwise sufficient awareness on the threats and consequences of early marriage in my surrounding community. In the beginning, the relationship was difficult and turbulent; it might have been the age gap. My husband even dared to hit me. However, when I gave birth to my first child, the relationship improved a little. Though to a lesser degree, we still fought, until I had my second child. I remember that my mother blamed me excessively for my early marriage; she also blames herself for accepting the marriage in the first place.”

b. “Not knowing how to run the house was the reason I got pattered”

From northern rural Aleppo, Wafaa M. (17) is another adolescent girl, who traditions and customs coerced into the realm of motherhood, where she became a mother to two children, Yazan and Ahmad, while she was yet a child in need for care herself. In 2018, Wafaa was forced to marry a man 10 years older than her, when she was only 15 years old. They quarreled, she was pattered and subjected to violence, which Wafaa attributed to several reasons, mainly her lack of maturity, and thus their inability to understand each other. She said:

“Watching my friends, I could see the spirit of childhood I was deprived of, for most of them are still being treated as children who are yet growing up. In the community, where I was brought up, society observes 22-year-old unmarried women as spinsters, who will never get married for being too old. Regarding the violence I was subjected to, the reason was that I did not know how to run the house the way my husband wished, for I did not have enough time to learn before getting married. My husband keeps comparing the way I manage the house with his mother’s, who is 45 years old. Despite this, I am still married, for I do not want to be a divorced woman.”

c. “A child making a living for a child”

Fatima W. (15) lives in the Shmareen camp, near Azaz city. She works at a sewing workshop to make a living for her toddler Ammar, who is 7 months old. In 2019, Fatima was about to turn 15, when she married a relative, who was too young himself, being 18 years old. The marriage lasted for 14 months only, after which they got a divorce, and Fatima ended up being her son’s sole breadwinner. She said:

“I am today treated as a divorced woman, a label that has dire social connotations, for I was denied pursuing my education like the rest of my peers. Consequently, I learned sewing and embroidery to make a living for my child, given my father’s poor economic conditions, for he works as a builder, and the money he makes for the day is not even enough to cover the price of bread he buys for my siblings.”

d. “I was only 13 when I got married”

Zinab B. (15), from Kafr Hood town in northern rural Aleppo and displaced to the Sajo town, in northern rural Aleppo on the Turkish borders, was married in 2018, while yet 13 years old. She married her cousin under the command of inherited traditions and customs. She told STJ the following:

“We were engaged for about six months. On my wedding night, I was 13 and a half years old. In the beginning, my husband, who is my cousin, put me to too much suffering, for I was not used to this new life. As time passed, and when he started taking care of me, the problems gradually disappeared. A year into our marriage, I started showing symptoms of pregnancy. I always remember what the doctor told me the first time I visited her:

‘Are you mad, the two of you? You are a child pregnant with a child!’

I went through hell due to my early pregnancy, I developed anemia and calcium deficiency.”

She added:

“In fact, I cannot deny that early marriage has a severe mental impact on the girl, especially in the first year, which depends on the husband’s ability to help the wife through that phase. Girls must not marry men who are a lot older, so they would maintain a somehow close mindset. If the age gap is more than seven years, divorce will be the absolute result.”

-

Child marriage in areas held by the Autonomous Administration

In al-Hasaka province, held by the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, early marriages proliferate for economic and social reasons. The war also had exacerbated the phenomenon, for many children abandoned school and people feared for their girls from spinsterhood.

a. “You have no other place to go; you have to obey and idolize me”

“He still beats me sometimes, but I have come to terms with my situation after a long suffering. Of course, I am not planning to get a divorce and leave my children.”

Thus, Ruqaya A. described her marital life with her cousin, who is 10 years older than her. The 19 years old young woman is born in the city of al-Shadadi, south al-Hasaka city to a Muslim Arab family. Her father coerced her into marrying her cousin, who decided that she was his, under what is known as al-Hayar / Cousin Marriage,[6] in 2014, when she was yet 13 years old.

Later on, Ruqaya had three children, the youngest of whom is only a few months old, and two girls, three and five years old. She recounted the following to STJ:

“Despite my young age, for back then I was 13 years old, my father was forced to accept giving me in marriage to my cousin, otherwise the extended family would have turned against itself. I was against the marriage. However, my cousin would not have allowed me to marry someone else, for he has chosen me to be his wife under the tribal norms.”

Rukaya said that, in the beginning, her husband was affectionate and caring, but his behavior drastically changed as time passed. She added:

“A year into our marriage, we had a baby girl. This upset my husband, for he wanted a son. As if I had control over the child’s sex. He, then, started to beat me sometimes, without an obvious reason, and threatened to marry another woman who would give him a son. I abandoned him and sought my family’s home. I wanted a divorce. Nonetheless, all my relatives blamed me, as if it was my fault. They returned me to my husband’s house, who with delight over my misfortune, said: ‘cannot you see it? You have no other place to go; you have to obey and idolize me.”

Despite the domestic violence that Rukaya is still subjected to at the hands of her husband, she chose to stay with him, to be by her children’s side, and so they would not have to deal with the consequences of her marriage to their father. She explained:

“I asked for divorce several times, but my husband always deprived me of my children, so I had to back down and return to him every time. I did not want to lose my children or leave them at the mercy of another woman, he will marry after me. I had to adapt and accept the reality. He today hits me in front of the children sometimes. He even beats them if they interfere to prevent him or attempt to release me from his grip.”

b. “They denied me seeing my child”

Lila M. (18), Kurdish, is attending a private education institute in al-Qamishli city, preparing to take the preparatory school exams for 2020-2021, after she abandoned school for about three years due to her early marriage.

Lila lives with her parents in al-Qamishli city, attempting to start her life anew, but she cannot conceal her longing for her only son, after she got a divorce. She narrated the following:

“I got married in 2017, when I was only 15 years old. I left school to marry the young man I fell in love with, and who was several years older than me. Our love resulted in a child two years into the marriage. However, the babe was not enough to sustain the relationship, made weak by disputes and disagreements.”

Lila’s marital life ended with divorce, and she was deprived of her suckling son, who was less than a year old. Handicapped by tribal and social customs, she had to give up on his custody. Full of regret, she said:

“While married, we barely agreed, my husband and I. But still, I never thought of divorce, not for once. However, as the disputes grew acute, my husband divorced me and deprived me of seeing my son. None of the family members stood by me as to regain custody over my child. On the contrary, they all blamed me, because this marriage was my choice, saying that I had to deal with the consequences of my decision.”

Lila’s son today lives with his paternal grandmother, after her husband remarried following the divorce. Pursuing her education, Lila is attempting to start all over again, turning the page on a chapter, which she calls “dark”.

-

Serious pregnancy and delivery complications suffered by adolescent girls

Both the health and the life of girls are threatened by early marriage. Most of the time, girls, who are coerced into early marriages, get pregnant while yet adolescents, which makes them far more vulnerable to pregnancy and delivery complications, given their delicate bodies. Consequently, they face mental and health related problems, especially repeated miscarriages.

From Deir ez-Zor and displaced to Afrin in rural Aleppo, Ghalia M. is an adolescent who suffered a miscarriage after marrying her cousin at the age of 16, who back-then was 22 years old. She recounted the following to STJ:

“I married my cousin in April 2017. I had to abandon school for his sake; I feared that he might remarry. In the beginning, my family opposed the marriage. A few days later, they changed their mind. Three years into my marriage to Muhammad, disputes emerged, of the regular sort. Nonetheless, the disagreements exploded that he even started hitting me, for I got pregnant three times and miscarried every time. I could not give him the child he wanted. Then, my husband’s family started interfering, turning our life into a cycle of pain that I could not speak about, especially not to my family, who blamed me for choosing my husband and for marrying that early. What further worsened our life was that our marriage was not registered at the court. My life was like hell. My body, furthermore, withered down, I turned so skinny, that I weighed 39 kilograms, while being beaten by my husband. I thought that I had to be patient until I succeed in giving birth or dare to tell my family about my hellish life.”

Born in Hama and displaced to Barisha camps in northern Idlib, Hana B. is another child bride, who was forced to marry in October 2018, while yet 14 years old. Hanna miscarried three times. She said:

“I had no desire to marry at the time. But my father insisted. My marital life was peaceful, till I got pregnant three times and miscarried every time. I finally gave birth to my daughter. My family never regretted having forced me to marry early. On the contrary, my father was overjoyed. However, when I repeatedly got pregnant and miscarried, which made me both mentally and physically weary, I could see regret in his eyes, knowing that no one guided or advised me on early marriage, not even the sheikh that carried out the marriage ceremony. He never attempted to raise my awareness concerning the risks posed by early marriage. We at least managed to register our marriage at the court later on.”

Rania S., a third case, is from the Ma’saran town, southeastern Idlib and displaced to the Dair Hassan camps in northern Idlib. She gave birth to a child when yet 17 years old. The child, however, died shortly. She narrated the following to STJ:

“In late 2017, a sheikh wedded me to a 23 years old man. We did not register the marriage at the court. Our relationship was stable despite the age gap. It was rather priming. Soon after we got married, I got pregnant and gave birth at the eighth month, which caused the child to die.”

Born in Hama and displaced to camps set up in Armanaz city, Idlib province, Aya M. was also forced to marry at the age of 16. He father was dead and her mother could not make ends meet. She said:

“In 2017, I was not 16 yet, when a young man, 19 years old, proposed to me. We were wedded by a sheikh but did not register our marriage at the court. We started our marital life like any other couple, but in time problems and difficulties took the best of us, as I could not get pregnant. My husband took me to several specialized women gynecologists, who attributed my condition to my young age and my body’s inability to endure the pregnancy. My husband never beat me, but our life was a nightmare due to the many disputes we had.”

-

Early marriage breaking records in several Syrian areas

In the past a few years, child marriage grew out of proportion in several Syrian areas, particularly in Idlib province, where it broke records especially in 2018 and 2019, according to Aliya Rasheed, a women’s rights activist based in Idlib. Child marriages, she said, surged, breaking the mark of 70% out of all the marriages in the past two years, due to the lingering war that resulted in poverty, displacement, integration of communities, displacement and unemployment on the one hand, and traditions that encourage child marriage on the other. Rasheed recounted the following to STJ:

“Of the cities and towns in Idlib province that witnessed an acute increase in child marriage cases are Ma`arat al-Nu`man and Kafar Takharim, in addition to the towns of Sannfara, Ayn Laroz and Maarzita, where moral heritage rules, rather than traditional beliefs. There, child marriages exceed 70% of the total cases. In the towns of Maartahrme, al-Bara, Jisr al-Shughur, Salqin and Idlib, child marriages proliferate due to customs and traditional beliefs, which label girls as spinsters if they continue to be unmarried at the age of 18. In these areas, however, child marriages hit more than 65%, where girls cannot refuse marrying as to keep up their education or wait for the suitable person, unlike the religious heritage, which coerces a girl into marriage once her parents approve the suitor. Nevertheless, girls in some towns and cities are granted the freedom of marriage, being in a relationship and pursuing their education, like in al-Dana, Saraqib, Khan Shaykhun, parts of the cities of Harem, Salqin, and Idlib, where child marriages are fewer than 35%.”

In northern rural Aleppo, an informed source reported that early marriages in the area mounted to 60% out of the total marriages in the past two years, adding that early marriage has found its way into familiarity among the area’s people.

In al-Hasaka province, held by the Autonomous Administration, Arzo Tammo, the Pattered Women Committee official, under the SARA Organization for Combating Violence against Women, said that child marriage in al-Hasaka province has this year recorded fewer figures compared 2019. The organization documented 36 child marriages in early 2020, while it recorded 46 cases over the course of 2019.

Tammo stated that early marriages spread in al-Hasaka province’s suburbs and villages, more than it does in city centers, pointing out to the negative consequences of early marriage, which she described as one pattern of violence against women:

“Numerous families force their adolescent girls to marry at an early age, thus pushing divorce and family fragmentation to higher ratios. Furthermore, adolescent girls cannot handle marital life’s burdens. They also give birth to babies while so young themselves, due to which they will not be capable of raising children properly, as they are not allowed to reach the necessary maturity on all levels.”

Moreover, Tammo added that the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria attempted to prevent child marriages in its areas of control, and passed a resolution in 2014, which banned marriages under the age of 18 and polygamy.

Empowering women, she noted, is one of the essential means to combat the phenomenon, adding that SARA had on 28 October 2019 concluded a nine-month-campaign in northeast Syria, which grabbled with all forms of violence against women, entitled “Do not Murder Women, Women are Life”, which encompassed lectures, seminars and activities that focused on the necessity to combat violence women are subjected to.

According to STJ’s field researcher, the Internal Security Forces / Asayesh, affiliated with the Autonomous Administration, arrested two men in Amuda city in 2020, for seeking to wed the first man’s adolescent daughter to the second’s son, in exchange for the money the first had loaned from the second. Asayesh prevented the marriage and arrested the two men.

-

Early marriage’s dire consequences for girls

According to the United Nations / UN, child marriage denies girls the right to choose whom and when to marry – one of life’s most important decisions. Choosing one’s partner is a major decision, one that should be made freely and without fear or coercion. Furthermore, child marriage directly threatens girls’ health and well-being. Marriage is often followed by pregnancy, even if a girl is not yet physically or mentally ready. Complications from pregnancy and childbirth are the leading cause of death among adolescent girls aged 15 to 19.[7]

Additionally, girls who are married may also be exposed to sexually transmitted infections, including HIV. When girls marry, they are often forced to drop out of school so they can assume household responsibilities. This is a denial of their right to an education and job opportunities in the future, which will have a long-term influence on their families, for girls who leave school have worse health and economic outcomes than those who stay in school, and eventually their children fare worse as well.

-

Alarming negative effects of early marriage prevalence

One of the most prominent negative consequences of early marriage in different regions of Syria, especially those under the control of opposition armed groups in Idlib and the northern countryside of Aleppo, is the increase in divorce cases as a result of the couple’s inability to understand marriage as an institution, due to their young age. Nevertheless, the most dangerous consequence is perhaps the difficulty of registering these marriages at official departments, according to Judge Muhammad Nour Haimidi, who said that most of the marriages in Idlib province have not been registered at the specialized Sharia courts belonging to Hayat Tahrir al-Sham /HTS, for these courts have not been granted an official recognition. Worse yet, marriages are not registered in the courts in areas held by the Syrian government, as a result of families’ fear of arrest if they go to these areas, in addition to the high costs of marriage proceedings and family books when husbands attempt to obtain them illegally.

Therefore, failure to register marriages leads to serious consequences, especially for the wife and children. On top of these is that wives are indeed deprived of the recognition granted by official registration and, thus, are denied carrying out family affiliation proceedings for their children. Women are also robbed of their right into inheritance, or dowry and other marital dues incases of dispute. The greater risk is, however, suffered by children who might grow up almost stateless, when a marriage is not registered and neither a birth certificate nor any official documents are obtained. Under such circumstances, children tend to be deprived of the right to education, job opportunities, inheritance, and forming a family, Haimidi said, explaining that:

“Of early marriage’s consequences is the suffering that adolescent girls have to endure, particularly because many of these girls are not mature enough to get married, speaking of proper and healthy physical growth. This might have a tragic impact on the girl’s health and body. There is no doubt, that the leading cause to the spread of early marriage is the prevalence of illiteracy and ignorance as children continue to drop out of schools, especially in the past a few years, not to mention the parents’ failure to keep a track of their children’s education. It is worth noting that one of the greatest risks that early marriages pose to society is over reproduction, for women start giving birth at the age of 16, sometimes before, until they are 40 years old, which boosts the population’s density in ways that burden society.”

The same applies to areas in northern rural Aleppo, for numerous marriages there are not registered in the civil registries in the areas held by the Syrian government, for fear of arrest. Consequently, families contend themselves with registering the marriage at local civil registries, while others do not attempt registration altogether, according to information obtained by STJ.

[1] The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) defines early or child marriage as any formal marriage or informal union between a child under the age of 18 and an adult or another child. Though child marriage pertains to both girls and boys, it disproportionately affects girls the most.

[2] Most of the area is controlled by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham / HTS.

[3] Controlled by Turkey-backed National Army.

[4] “When caged birds sing: stories of Syrian adolescent girls,” UNFPA, March 2019. Last visited: 25 August 2020. https://arabstates.unfpa.org/en/publications/when-caged-birds-sing-stories-syrian-adolescent-girls

[5] “Adolescent girls wedded more than once! UNPFA: Child marriage rose to 46% under the crisis in Syria,” al-Watan, 11 March 2019. Last visited: 25 August 2020. https://alwatan.sy/archives/190376?fbclid=IwAR1wuBGbPSH7Ho1ZfjGbrC1ebuavq8yqFWi78WgIbOsod42v_aW49WzJ_RE

[6] Zawaj al-Hayar or cousin marriage is where a girl is chosen by a cousin since childhood and is, thus, united exclusively with that cousin, whom she is coerced to marry. This marriages are still common among tribal communities, which continue under several justifications. These marriages are mostly conducted before puberty — that is when the girls are not 15 years old yet. The problem is that the marriage is pursued through coercion or regardless of the couple’s feelings, or whether they are in love or not. These marriages are carried off law, and despite the fact that they oppose the rulings of Islamic Sharia.

[7] For further details, refer to: “Child Marriage,” UNPFA. Last Visited: 27 August 2020. https://www.unfpa.org/child-marriage

4 comments

[…] daughters’ lives. Child marriage has become more common during Syria’s war, and in the last few years particularly in the northwest (as well in refugee […]

[…] daughters’ lives. Child marriage has become more common during Syria’s war, and in the last few years particularly in the northwest (as well in refugee […]

[…] “Early Marriage Hits High Rates in some Areas of Syria,” STJ, 17 September 2020, https://stj-sy.org/en/early-marriage-hits-high-rates-in-some-areas-of-syria/ (last accessed: 24 June […]

[…] [xlvi] al-Watan, “Adolescent girls wedded more than once! UNPFA: Child marriage rose to 46% under the crisis in Syria,” (Mar. 11, 2019). Also available online at https://alwatan.sy/archives/190376?fbclid=IwAR1wuBGbPSH7Ho1ZfjGbrC1ebuavq8yqFWi78WgIbOsod42v_aW49WzJ_RE; Syrians for Truth & Justice, Early Marriage Hits High Rates in some Areas of Syria, (Sep 17, 2020), 5. Also available online at https://stj-sy.org/en/early-marriage-hits-high-rates-in-some-areas-of-syria/. […]