1. Methodology

Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) started working on this report in mid-2018. Ahead of field work, a team of researchers discussed the report’s methodology, set up a plan, and defined target villages and regions. In early 2019, the team embarked on obtaining testimonies and conducting interviews — 31 witnesses were interviewed in person throughout northeastern Syria, particularly in the villages where lands were seized. The researchers conducted 12 online interviews, reaching out to witnesses several times in 2020, as to obtain additional accounts and information.

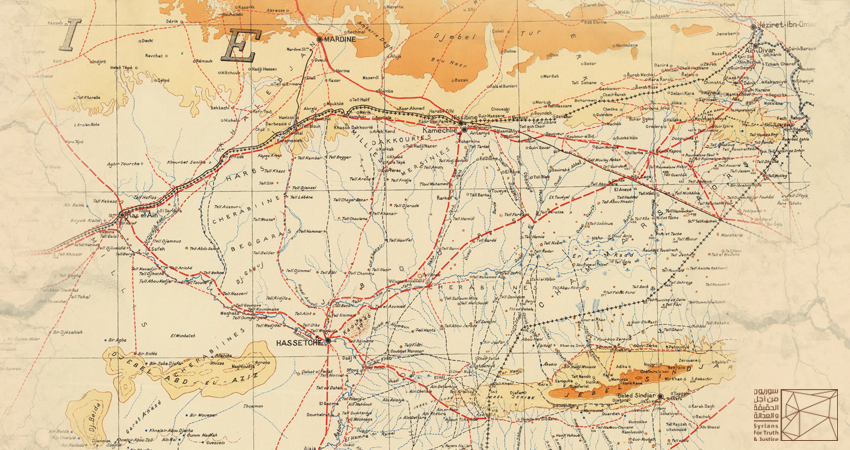

In addition, a number of witnesses provided STJ with 27 exclusive documents, that are to be published for the first time, which indicate the areas of properties confiscated by the subsequent Syrian governments. A different set of documents, however, reports incidents related to the subject matter, not to mention the maps, which depict the target region, under the Ottoman Empire and the French Mandate.

For the aim of this report, the researchers also cited 77 references, including 34 books and 43 research papers, studies, magazines, articles and reports, which addressed the report’s subject matter or included related materials.

Furthermore, STJ sent a mission to the French city of Nantes, which examined materials of the French archive. Another researcher made a thorough reading of Turkish documents, some of which were written in the Ottoman Turkish language, and quoted them when necessary.

2. Executive Summary

24 June 2020 marked the 46th anniversary of one of the large-scale projects aimed at bringing about demographic changes, which have been in the planning since before 2011. This was also the day the National Command of the Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party passed resolution No. 521 in 1974, which provided for the effective implementation of what was termed the ‘Arab Belt’ project. At that point, thousands of Arab families who lost their homes to the creation of Lake Assad, were prompted to move and settle in ‘model villages’, that were built on lands seized earlier under the Agrarian Reform Laws, starting with Act No.161 of 1958, the year of the establishment of the unity between Syria and Egypt.

Towards the promotion of Arab nationalism at the expense of the Kurdish identity in Syria; as described by international human rights organizations, the Syrian Arabs were transferred by government to settle in the Kurds’ home areas with the aim of establishing the ‘Arab Belt’ along the length of the border strip with Turkey, which meant to separate the Kurds of Syria from those of Turkey and Iraq. The planned demographic change also included deporting the Kurds residing in villages within the scope of this ‘Belt’ to other areas.[1]

Contrary to what is commonly said, it seems that the memorandum submitted by Muhammad Kurd Ali, Minister of Education in Taj al-Din al-Hasani’s first government,[2] to the heads of ministries, dated 18 November 1931, was one of the first official recommendations, which explicitly called for the deportation of the Syrian Kurds from their areas along the northern borders for national reasons. Talking about the situation of al-Hasakah province (then called Jazira), Kurd Ali referred to the migration of Kurds, Syrians, Armenians, Arabs and Jews to the border area adjacent to Turkey, saying that the Kurds, who were the largest in number, should be displaced to areas far from the borders of Kurdistan, proposing to grant them lands around Homs and Aleppo and to integrate them with the Arabs there.[3]

Also, in the context of the initial application of the Arabisation policy, the Central National Government appointed in late January 1937, Emir Bahjat al-Shihabi, who manned the military administration during the period of the Arab government, as a governor of al-Hasakah. Al-Shihabi came with a plan in his pocket, which he quickly launched. That plan aimed to ‘cleanse’ the small government administration of local employees from the Syriacs and Armenians, affiliated with the previous regime, and recruit new staff from the Arabs of Aleppo.[4]

Since the Ottoman era at least and until the declaration of Agrarian Reform Law No. 161 on 11 June 1958, the form of ownership throughout present-day Syria was feudal, as large areas were in the hands of a few people who were mostly notables, sheikhs of clans and princes.[5]

Law No. 161 determined the maximum admissible land ownership and provided for the confiscate of excess areas. However, the implementation of the law in al-Hasakah, specifically in areas historically inhabited by the Kurds, count on political considerations; this was illustrated in the projects carried out in the following years, which consisted of arbitrary seizing of properties, especially that of Kurds, and giving them to Arabs of clans who lived in the vicinity and/or to those who were later transferred from other Syrian regions.

By looking at the facts and events which followed the unity between Syria and Egypt in 1958, one can tell that the first building block for the demographic changes in areas of northern al-Hasakah province, western Tell Abyad town, Raqqa province, and Afrin region in Aleppo province, was laid at the stage of establishing the United Arab Republic (UAR).

In the political period that was named by historians as the ‘separation era’, specifically in 1962, a special census was conducted in the province of al-Hasakah, whereby tens of thousands of Syrian Kurds were stripped of their nationalities, which resulted in:

- Impossibility of proving ownership of lands which belong to persons rendered stateless.

- Kurdish peasants who lost their nationality didn’t entitled to lands distributed according to Law No. 161 and its subsequent amendments.[6]

In parallel, successive Syrian governments focused on suppressing the Kurdish identity, by restricting the overt use of the Kurdish language in schools and/or in the workplace, with the prohibition of publications in the Kurdish language, and the celebrations of Kurdish holidays, such as Nowruz, for decades. This was led to the Kurds in Syria being subjected to serious human rights violations, just like other Syrians, but, as a minority group they suffered identity discrimination.[7]

The ‘Arab Belt’ project was effectively implemented in the 1970s. That belt stretches in a length estimated at 300 kilometres along the Turkey-Syria border strip (starting from the far northeast of the Dêrik/al-Malikiyah district to the administrative borders with Raqqa province, west of the Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê), with a depth of 15 kilometres at its innermost point. Thus, about 4000 families from the Arab tribes in the countryside of Raqqa and Aleppo – especially from villages flooded with water that gathered behind the Euphrates Dam/Tabqa Dam – were transferred and settled in model villages within the belt. That was done under the banner ‘building the new society’ uttered by the late Syrian president Hafez al-Assad in a speech he gave at the opening of the dam, addressed to the people of al-Ghamr area, [8] and others who will start a new life in the Euphrates basin.[9]

An ad hoc committee was established for the implementation of the ‘Arab Belt’; it was called ‘al-Ghamr Committe’ by the Ba’ath Party. One of the goals of this commission was to induce the Arab tribes in the flooded area to move to the new housing areas. For the completion of the plan, security and executive authorities were ordered to prepare the ground in al-Hasakah, thus, visits to representatives of these clans were organized throughout a whole year, in order to inform them of the areas where they were to be settled and the land they would invest.[10]

The al-Ghamr Arabs refused to bury their dead in their new residential areas, but rather moved them to Raqqa until the early 1980s. Further, quite a few of them refused to build mosques without the approval of the original owners of the land, while others refused to use the siezed lands incocme to travel to Hajj, without the consent of the original owners. This indicates that the Arab tribes rejected this plan.

Besides its political aims and disastrous effects – especially social ones – the ‘Arab Belt’ project constitutes a flagrant violation of Syrian laws themselves; the permanent Syrian constitution of 1973, under which the bulk of the project was implemented, provided in its article 15:[11]

Private ownership shall not be removed except:

- In the public interest by a decree;

- Against fair compensation;

However, neither of the two conditions were met in the implementation of the ‘Arab Belt’ project, as the expropriation was for the benefit of other Syrian citizens, who are different only in terms of language and nationalism.

Moreover, this policy, which has been pursued by successive governments of Syria, violates the principle of equality between citizens in rights and duties, in accordance with Article 25 of the 1973 permanent constitution.[12] As removing ownerships from Syrian Kurds and granting it to Syrian Arabs without any legal justification or court ruling, is a clear discrimination and favouritism. This policy also violates Article 771 of the Syrian Civil Code promulgated by Legislative Decree No. 84 of 1949, which affirmed that no one may be deprived of his property except in cases determined by law, and in return for fair compensation.

3. Recommendations

Property restitution should be viewed and implemented in the light of the current political process in Syria, since that will have political and fateful dimensions that will positively affect millions of Syrians. The success of this process will contribute to the success of Syria’s peace process, which will provide a safe and neutral environment and will encourage Syrians to participate in public life, especially in elections, and will also build confidence in the constitution that can be drawn up later. Therefore, STJ would like to address recommendations:

A. To the United Nations (UN)

-

-

- To ensure inclusiveness, fair and genuine representation of all Syrians – regardless of their affiliations – in all political negotiations, especially those related to the Syrian constitution, to assure that all issues of individuals and the groups to which they belong are included.

- To ensure that the new Syrian Constitution guarantees equal rights for all Syrians and prohibits any kind of discrimination – particularly on the basis of race, colour, descent, national or ethnic origin – having the purpose or effect of impairing or nullifying the recognition, enjoyment or exercise by all persons, on an equal footing of all rights and freedoms.

- To work seriously towards a wider representation of civil society organizations, especially those active in documenting human rights violations and restitution of property and whose work is inclusive and non-discriminatory, in all areas.

- To provide equal technical and logistical support to Syrian civil society organizations and initiatives working on documenting cases of expropriation, in all Syrian regions, and to support the creation of a unified national database for the entire Syrian Republic.

-

B. To Constitutional Commissioners

-

-

- To pledge to include all discriminatory projects, that was taken before 2011 against the Syrian Kurds and other Syrian citizens, on the agenda of the current Constitutional Committee and in the negotiations to find a political solution, and to propose fair solutions to all victims without exception.

- To pledge to ensure the writing of a non-discriminatory constitution based on equal rights and citizenship to all Syrians, along with ensuring the return of expropriated property to its original owners in any part of Syria, and ensuring the safe, dignified and voluntary return of all displaced persons and refugees to their homes and forming special committees to assess and provide fair compensations for them.[13]

- To place the so called ‘Arab Belt’ project and similar discriminatory projects on the negotiating table of the new Syrian constitution (to be written), so that they will be taken into consideration in the drafting process.

-

C. To actors in the Syrian conflict (the United States – the European Union – the Arab League – the Russian Federation – the United Kingdom)

-

-

- To ensure the prohibition of current and future discriminatory projects that are taken against the Kurds or other groups of Syrian people in any part of Syrian.

- To determine the dimensions of the Turkish plan aiming at demographic changes in the Syrian territories it occupied along the northern border strip, and to ensure that projects help in this are not funded.

- To ensure the return of all forcibly displaced people from Afrin, Tell Abyad and Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê, and all other Syrian regions, to their homes, and also to ensure the return of expropriated property to its original owners, and the accountability for all those involved in human rights violations.

- To work to restore Syrian citizenship to those who have been stripped of it under the extraordinary census of 1962.

-

D. To owners of expropriated property

-

-

- To keep the originals of all court decisions and any other documents proving ownership in a safe place.

- To keep copies of all documentation with a reliable, honest and known third party if necessary.

-

E. To the current Syrian government and/or future governments

-

-

- To form a neutral, independent and impartial Syrian national committee to study how to end the so called the ‘Arab Belt’ project and other similar discriminatory projects which resulted in the seizure of people’s property, and also to study the ownership documents submitted by claimants, and decide their cases fairly and expeditiously, provided that the decisions of the aforementioned committee are subject to appeal before the competent courts in accordance with the Syrian laws, and that all results are published in full transparency in the public and in official newspapers.

- To entitle any formed committee to study both; the issue of the landowners who were deprived from their lands and that of people whose lands were flooded and thus transferred to Jazira – we actually see them as victims of the racist project conducted by the Ba’ath government – and to ensure fair compensation for all.

- To not to neglect the social dimensions of discriminatory projects on any Syrian component, and to work seriously to make real reconciliations between all parties, as well as looking forward to building a peaceful future which ensures full equality of rights and duties in Syria.

-

F. To the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic and the International Impartial and Independent Mechanism (IIIM)

-

-

- To Ensure inclusiveness during the documentation process of violations committed by all parties to the Syrian conflict, especially those that led to the forcible displacement of millions of Syrians from their home areas.

-

To read the full report (121 pages) in PDF format, please click here.

[1] “Group Denial: Repression of Kurdish Political and Cultural Rights in Syria”, HRW, 26 November 2009, https://www.hrw.org/report/2009/11/26/group-denial/repression-kurdish-political-and-cultural-rights-syria (last visit: 4 September 2020).

[2] “The First Government of Taj al-Din al-Hasani”, Syrian Modern History, https://syrmh.com/2018/10/21/%d8%ad%d9%83%d9%88%d9%85%d8%a9-%d8%aa%d8%a7%d8%ac-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%af%d9%8a%d9%86-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%ad%d8%b3%d9%86%d9%8a-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%a3%d9%88%d9%84%d9%89/ (last visit: 4 September 2020).

[3] Muhammad Kurd Ali: “Almozakart/The Diaries”, the second part, Dar Adwaa al-Salaf for publication and distribution, book number 2775/2010, pages 440-442. To download the book please visit: http://www.dimoqrati.info/?p=52101 (last visit: 4 September 2020).

It is important to note that Muhammad Kurd Ali mentioned in one of his diaries that he was born to a Kurdish father and a Circassian mother.

[4] Muhammad Jamal Barout: “The modern historical formation of Syria’s Jazira – Questions and problems of the transition from Bedouin to urbanization”, Arab Centre for Research & Policy Studies, first edition, Beirut, November 2013, pages 416 and 417.

[5] Azad Ahmed Ali: “The Role of Agriculture and Grazing in Mapping the Population of the Euphrates Island”, Medarat Kurd, 22 March 2020, https://www.medaratkurd.com/2020/03/%d8%af%d9%88%d8%b1-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b2%d8%b1%d8%a7%d8%b9%d8%a9-%d9%88%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b1%d8%b9%d9%8a-%d9%81%d9%8a-%d8%b1%d8%b3%d9%85-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%ae%d8%a7%d8%b1%d8%b7%d8%a9-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b3%d9%83/ (last visit: 4 September 2020).

[6] “Syrian Citizenship Disappeared: How the 1962 Census destroyed stateless Kurds’ lives and identities”, STJ, 15 September 2018, https://stj-sy.org/en/745/ (last visit: 4 September 2020).

[7] “Syria: Kurds in the Syrian Arab Republic One Year after the March 2004 Events”, AMNESTY International, 28 February 2005 https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/MDE24/002/2005/en/ (last visit: 4 September 2020).

[8] The term ‘al-Ghamr area’ was used during the preparation and implementation phases of the project by its designers themselves, and this was subsequently led to the Arabs who were transferred being named as ‘Maghmurin’ or ‘Arab al-Ghamr’ which means the affected by flooding.

[9] President Assad website, (The attached link was active until the research team’s last visit on 27 March 2020, but it became invalid on 9 July 2020), http://www.presidentassad.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=352:5-7-1973&catid=255&Itemid=493

[10] Abdul Samad Dawood: “Arab Belt in Jazira, Syria (Qamishli- Syria, issued by the Kurdish Party of Yekiti in Syria, 2nd edition 2015, page 53.

[11] This article is also contained in Syria’s 2012 Constitution, and in the same number, the full article reads:

Article 15: Collective and individual private ownership shall be protected in accordance with

the following basis:

- General confiscation of funds shall be prohibited;

- Private ownership shall not be removed except in the public interest

by a decree and against fair compensation according to the law;

- Confiscation of private property shall not be imposed without a final

court ruling;

- Private property may be confiscated for necessities of war and

disasters by a law and against fair compensation;

- Compensation shall be equivalent to the real value of the property.

For more info, please check: https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Syria_2012.pdf

[12] Article 33 of the Syrian Constitution of 2012 stipulates that citizens are equal in rights and duties, and there is no discrimination between them on the grounds of sex, origin, language, religion or belief.

Article 33 Text:

- Freedom shall be a sacred right and the state shall guarantee the personal

freedom of citizens and preserve their dignity and security;

- Citizenship shall be a fundamental principle which involves rights and duties

enjoyed by every citizen and exercised according to law;

- Citizens shall be equal in rights and duties without discrimination among them

on grounds of sex, origin, language, religion or creed;

- The state shall guarantee the principle of equal opportunities among citizens.

[13] In one of its reports, AMNESTY International explains in detail how the Kurds in Syria have been subjected to serious human rights violations, as other Syrians, and how, as a group, they suffer identity-based discrimination, including restrictions placed upon the use of the Kurdish language and culture. It also said that large proportion of the Syrian Kurds are effectively stateless.

For more info, please check: “Syria: Kurds in the Syrian Arab Republic One Year after the March 2004 Events” AMNESTY International, 28 February 2005, https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/MDE24/002/2005/en/ (last visit: 4 September 2020).

2 comments

[…] To read the original post, with references etc click HERE […]

[…] [lxvi] STJ, Deprivation of Existence: The Use of Disguised Legalization as a Policy to Seize Property by Successive Governments of Syria, (2020). Also available online at: https://stj-sy.org/en/deprivation-of-existence-the-use-of-disguised-legalization-as-a-policy-to-seiz… […]