-

Executive Summary

The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) embarked on numerous raids and arrested dozens of people in its control areas in Deir ez-Zor province, located east of the Euphrates River, during the “Deterrence of Terrorism” campaign it first launched on 4 June 2020 against the cells of the Islamic State (IS), aka Daesh.

The reported raids and arrests were spearheaded by the security services of the Autonomous Administration and the SDF, particularly by the Anti-Terror Forces, known as the HAT.[1] Some of these raids were covered by helicopters of the US-led coalition, eyewitnesses claimed.

In the wake of the campaign’s first stage, the SDF announced that it arrested and detained 110 persons on the charge of belonging to IS, in a statement made on 10 June 2020,[2] adding that it also swept large-scale areas in the suburbs of Deir ez-Zor and al-Hasakah provinces. It also arrested and detained other 31 persons during the campaign’s second stage, according to the corresponding statement made on 21 July 2020 that reported the outcomes of the 4-day operation in rural Deir ez-Zor.[3] “At the end of the [campaign’s] second stage, the participant forces managed to achieve the planned goals,” the SDF said, pointing out that it arrested 31 terrorists and suspects, one of whom it described as a high-ranking IS commander.

Contrary to SDF’s reports, as it declared arresting a total of 141 persons over the course of the campaign between 10 June and 21 July 2020, information obtained by JFL and STJ, that are backed by a thorough investigation process, indicates that the SDF arrested no fewer than 339 persons in Deir ez-Zor province alone, from the outset of the first stage of the “Deterrence of Terrorism” campaign on 4 June to late August 2020. Furthermore, the fate of 44 of those detainees is unknown, since 200 persons are already released, while about 90 others are being brought before the court, the field researchers of the two organizations reported, adding that among the persons arrested were a number of teenage boys, who are not yet 18 years old.

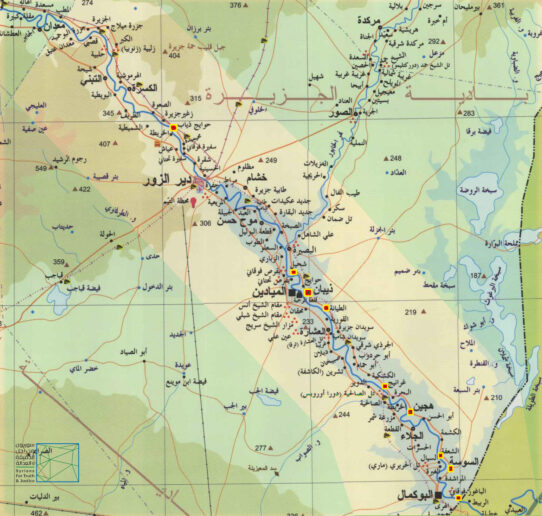

During the campaign, the raids and arrests targeted several towns in Deir ez-Zor province, primarily Hajin, Gharanij, Diban, al-Shheell, Huwayej Diban, al-Tayyana, Ash Sha’Fah and al-Baghouz.

Image no. (1) -The map locates the towns targeted by the campaign.

Furthermore, the JFL and STJ documented the arrest of no less than 29 persons in February 2020, of whom 23 are released, while the remaining six continue to be detained at the al-Kasra prison, west of Deir ez-Zor city.

For the purpose of this report, the partner organizations reached out for sources, eyewitnesses and relatives of detainees in Deir ez-Zor province, who addressed the reasons for and the way the detentions were carried out. Three of the interviewees are relatives of detainees, who got detained during the “Deterrence of Terrorism” campaign, including a minor boy, 16, a university student and a young man, who is his family’s sole breadwinner. While none of the relatives were informed of the reasons for the arrest, the fate of the three detainees was yet unknown at the time of reporting in late September 2020.

Moreover, the report provides the testimonies of two former detainees, arrested and detained by the SDF earlier on and for various charges, most notably belonging to IS. Both of the witnesses reported maltreatment, which at times amounted to beating and physical abuse.

In a report published on 14 August 2020,[4] the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic stated that security deteriorated as the SDF ramped up raids and arrests against civilians, who are allegedly affiliated to the Islamic State in the Levant and Iraq (ISIL), so-called Daesh in Arabic, adding that:

“The Commission documented eight cases of arbitrary detention of civil society workers, political activists and persons of Arab ethnicity by the Syrian Democratic Forces and affiliated Kurdish People’s Protection Units/Women’s Protection Units, including by their military intelligence. Civilians were apprehended in towns in Raqqah and Hasakah Governorates and held in various intelligence facilities under the control of the Syrian Democratic Forces, as well as in Ghweran Prison, the Al-Shadadi prison, the former Raqqah juvenile prison, and Ayed, Al-Aid and Ayn al-Arab (Kobani) prisons.”

The SDF carried out similar raids and arrests in Raqqa province in August 2019, which affected no less than 14 civilians, including well-known activists of civil society organizations.[5] Four of the detainees were released later on.[6]

-

Background

Over the course of the Syrian conflict, several of the fighting forces held reigns to power in Deir ez-Zor province. In June 2012, armed opposition groups took over Deir ez-Zor city, thus dividing it into two separate enclaves, controlling the one encompassing the majority of its neighborhoods, except for the al-Jorah, al- Qosoor, and Harbesh neighborhoods, as well as large-scale areas of the city’s countryside, which made the second enclave that the Syrian regular forces controlled. In July 2014, IS acquired dominion over the area previously held by the armed opposition groups following hostile confrontations. Later on, the Syrian regular forces and affiliated militias regained the city’s part lying south of the Euphrates.

In September 2017, backed by the US-led coalition, the SDF launched Operation al-Jazeera Storm in Deir ez-Zor. This massive drive led to SDF’s control over the province’s areas east of the Euphrates, chiefly the towns of Hajin, al-Kasra, Diban, al-Suwar, and al-Busayrah.

Regardless of the ruling parties, civilians were repeatedly subjected to all sorts of grave violations of human rights. In addition to death due to the shelling, civilians suffered from summary execution, arbitrary detention, forcible displacement, and property confiscation.

Even though active combat has ceased and the SDF has established its control over the areas in northeastern Syria, including those located to the east of the Euphrates River in Deir ez-Zor province, some of these violations are still committed, most notably arbitrary detention. Numerous residents of Deir ez-Zor were arbitrarily arrested, including under-18 teenagers.

A number of the reported arrests/detentions took place during the first stage of the “Deterrence of Terrorism” campaign, which started on 4 June 2020. The operation was carried out 175 km along the border strip and 70 km deep into the area, namely as far as the borders of al-Baghouz town, resulting in the arrest of over 110 persons, suspected for belonging to IS, the SDF stated.

Other arrests took place during the second stage of the “Deterrence of Terrorism” campaign, which the SDF launched on 16 July 2020, allegedly at the request of the locals and tribes’ dignitaries, who demanded that the SDF prosecute IS cells in eastern rural Deir ez-Zor. During the second operation also, the engaging forces, namely the HAT, the People’s Protection Units (YPG), Asayish and the Commandos Units committed several violations that resulted in the arrest of more than 31 persons.

On 15 September 2020, one last raid was carried out, targeting the al-Busayrah town. No less than 10 military vehicles stormed the town, accompanied by heavy firing in the air in search of wanted persons. The locals, for their part, held protests in various towns and villages, condemning the arbitrary arrests and the security chaos, as numerous assassinations took place in the area. Furthermore, a number of Syrian organizations released a joint statement on 20 August 2020, denouncing the repeated assassinations that aimed at tribal leaders in Deir ez-Zor, and demanding that the US-led coalition and the SDF assume their responsibility of maintaining security and protecting the locals.[7]

-

Testimonies of Victims and Detainees’ Relatives

In this section, LFJ and STJ provide five interviews, three of which were conducted with the relatives of persons detained by the SDF during the raids and arrests it embarked on throughout Deir ez-Zor under the “Deterrence of Terrorism” campaign, including a minor boy, 16, a university student, and a third man, his family’s sole breadwinner. The relatives were not informed of the detainees’ charges, whose fate was yet unknown at the time of reporting, particularly on 16 September 2020.

Moreover, the two organizations provide testimonies of two former detainees, who spent various durations at the SDF’s prisons early into the Syrian conflict. They were subjected to maltreatment, which at times amounted to beating and physical abuse, after they were both detained on various charges, the most serious of which was belonging to IS, the witnesses reported.

Born in Deir ez-Zor in 2004, Ammer M. was one of the children detained by the SDF during a raid into the al-Zir village. Offering the parents no explanation, SDF-affiliated personnel arrested Ammer on 1 July 2020, whose fate was still unknown at the time of reporting in late September 2020. Ammer’s maternal uncle recounted the following to STJ:[8]

“Ammer, a high school student, lived with his mother in the al-Zir village. On 1 July 2020, around 8:00 p.m. the SDF-affiliated HAT imposed a curfew. The village was cordoned in preparation for a raid, which allegedly aimed at clearing it of IS cells and terrorists, knowing that blasts and assassinations continue in the area; they have even escalated.

On the same day, we learned that the SDF personnel raided several houses and arrested many persons. One neighbor told us that the personnel raided my sister’s house and arrested her only child Ammer. Additionally, there were US-affiliated military vehicles on the village’s outskirts, which, however, did not storm in.”

Along with other family members, the witness tried to investigate into the evening raid. His wife managed to leave their house and headed to his sister’s. While none of the SDF personnel stopped her on the way, they did not allow her into the sister’s house, the witness said, pointing that the house was encircled and was being extensively searched. Stressing that his nephew was detained for no reason, the witness added:

“The next day, we referred to the SDF’s General Security Forces’ headquarters in the al-Busayrah town, near our own village, to ask for Ammer. A relative works there, as the officer in charge of the General Security patrols in the al-Busayrah. We recounted the evening incidents to our relative, who advised us to go to the Intelligence Directorate’s office, also in the same town. There, they offered us no information, saying that this was a security-related issue. Then, we addressed the officer in charge of the SDF’s Anti-Terrorism Department in Gharanij town, east of Deir ez-Zor. The officer was one of the personnel who raided the village, accompanied by the HAT. We went into the department’s building, which used to be an elementary school. He avoided helping us, saying that he could not intervene in issues related to raids and arrests. He also told us that we better refer to the headquarters in the al-Omar Oil Field, particularly since all the arrested persons are usually handed over to the US-led coalition forces stationed there. Nonetheless, because the oil field is a military zone and is run by the coalition’s forces, it is difficult to enter it and ask about someone. As for the local dignitaries, we got nothing other than empty promises from them, for their power is titular with no influence at all.”

A week after the evening raid, the witness reported, a group of the arrested young men was released, while the rest were still detained, but their parents were informed of their whereabouts, except for Ammer and two other young men, whose fate is so far unknown.

Born in Deir ez-Zor province in 1995 and a student at the University of Aleppo, Muhammad A. was also arrested from his home at the Ash Sha’Fah village by the SDF on 15 June 2020. His fate was still unknown at the time of reporting in late September 2020. Commenting on the young man’s arrest, a relative reported the following to STJ:[9]

“Muhammad was not a member of any political or military body; he even chose leaving Deir ez-Zor to Damascus during IS’ control over the area, fearing arrest and killings. It was not till 2018 that he returned to the Ash Sha’Fah village. On 15 June 2020, around 11:00 p.m. Muhammad was arrested by the SDF-affiliated HAT forces from his home on the 24th Street, at the center of the village. He was arrested during a raid after a curfew was imposed on the village, the thing they usually do every time they plan to storm an area. Muhammad, his maternal cousin and a group of the village’s young men were arrested, along with a group from surrounding villages. They were all arrested on the pretext of combating terrorism.”

A few days passed, but no news arrived on Muhammad’s whereabouts, the witness added. Accordingly, the family started visiting the SDF’s headquarters, dignitaries and influential figures, inquiring into Muhammad’s situation, asking them to play the mediator or help them to find the place where Muhammad was detained. Of the people they approached were Sheikh Mutasher al-Jad’an, one of the influential leaders of the al-Akidat/al-Aqidat tribe, who maintains relations with Kurdish commanders,[10] according to the witness, and the Commander of the Deir ez-Zor Military Council, dubbed Abu Khawla. However, all the family’s attempts at communication were to no avail. Commenting on this, the witness added:

“Asking about Muhammad’s detention place at the SDF’s headquarter, some officers told us that their mission ends once the detainees are handed over to the command of the US-led coalition. The decision was not theirs to make, they claimed. Other officers said that we had to refer to the Intelligence Directorate Command. We indeed went there, but the officials avoided answering our questions. We thus failed to get conclusive information on Muhammad’s fate. Furthermore, we were informed that Muhammad was handed over to the command in the al-Omar Oil Field, but we could never access the area, especially since the field is a US base and is a military zone.”

The witness added that the detainee’s relatives searched for him at all prisons and military headquarters and asked all tribe sheikhs and SDF commanders about his place. They even went to the cities of al-Qamishli and Kobanî to investigate into Muhammad’s whereabouts and his condition, but they found no trace of him, despite the fact that all the young men arrested on the same day were released or the prisons where they were held were known.

Furthermore, the witness said that US-affiliated helicopters were hovering over the area during the raid on the evening of 15 June 2020, the day Muhammad was arrested.

Born in the Burtuqala village in 1993, Deir ez-Zor province, Raafat A. was also arrested by SDF-affiliated personnel during a raid into his village on 13 July 2020. He is married and is the sole breadwinner of his family and younger siblings. Raafat’s fate was yet unknown at the time of reporting. Commenting on the incident, a relative of the detainee provided STJ with the following account:[11]

“On 13 July, SDF-affiliated personnel, backed by the US-led coalition and the Deir ez-Zor Military Council, declared they will launch the second stage of the ‘Deterrence of Terrorism’ campaign. One of the targets was the Burtuqala village. Back then, three US-led coalition helicopters landed in the village, around 12:30 a.m. For their part, the SDF personnel cordoned the village and started shooting in the air. On speakers, the personnel ordered the people out of their houses. They stormed about five houses and arrested several young men, including my relative Raafat.”

The next day, the witness stated, Raafat’s family asked the personnel stationed at an SDF-affiliated checkpoint about the previous day’s incidents, who said that they arrested an IS cell. The family then headed to the Deir ez-Zor Command Center, hoping to get answers about Raafat’s fate. There, they were told that their relative is detained in the Hajin city, Deir ez-Zor. Hearing this, the family went to search for Raafat in Hajin and al-Baghouz, as well as the al-Omar Oil Field, but they managed to obtain no information at all. The witness added:

“Raafat was married for three months only when he got arrested. He is also the sole breadwinner of his family, working at a grocery shop in the village. The villagers also know him as a fine man, who spends time either at home or work. It was not only Raafat that got arrested on the raid’s day, for the SDF personnel had arrested other young men too. Raafat’s family still does not know the slightest idea about his whereabouts, along with other three young men who got arrested on the same day. We repeatedly attempted to obtain information from the tribal leaders and the Deir ez-Zor Military Council, but we were offered nothing.”

For its part, the JFL obtained the testimonies of two former detainees, also arrested by the SDF, however, earlier into the Syrian conflict.

Born in Deir ez-Zor province in 1993, married and a father of two, Majed A. was arrested at the al-Kasra district in Deir ez-Zor by the SDF in February 2018.[12] Detained for several hours, he was subjected to beating and abuse, while offered no reason for his arrest.[13] Commenting on this, he said:

“Around 9:00 p.m. that day, I was riding my motorcycle home, returning from a friend’s house. I reached the center of the al-Kasra, near the municipality’s building, when I noticed two SDF vehicles behind me, boarded with a number of personnel, who ordered me to pull over. As I did so, masked personnel got out of the vehicles; they hit me on the shoulder and then shoved me down. Upset, I told them: ‘You do not have to push me; I will come with you.’ Two of the personnel stuffed me into one of the vehicle’s trunk and pulled my shirt over my head, so I would not see where they were taking me. They kept beating me all the way through, and I had a hunch that they were stopping all the people riding motorcycles.”

Majed added that he was driven to one of the SDF’s headquarters, which he later identified as a center affiliated with the Asayish, near the al-Kasra District Hospital. There, he was also beaten and then guided into the interrogation room, where he had to deal with two militants, one was in charge of taking the detainees’ possessions, cellphones and the like, and another who treated him roughly, and who later he knew as the guard of the director of the Asayish’s center in al-Kasara district. Recounting the details of the interrogation process, the witness said:

“As we were shown into the interrogation room, they put plastic cuffs around our rests. The personnel there asked us to keep our heads down. We were left with one militant, who was in charge of taking our possessions. He asked why we were arrested, and we answered that we were not informed of the reason, adding that they arrested us while on the street and in an abusive manner. Ten minutes later, another militant entered the room and started asking the first about us, the reason why were detained and also the reason why the guard of the director of the Asayish’s center in al-Kasara district was insulting us. We again answered him that we had no idea. The two militants are probably from Deir ez-Zor, their dialect indicated so. Then, the first militant, extremely disturbed, pointed to the second and said: ‘Make sure to lock the door and do not allow anyone to touch them until comrade Juwan, the director of the center, is here. I will arrest anyone who attempts to lay a hand on them’.”

Majed added that the plastic cuffs were loosened shortly after, and then another militant got into the room and started talking about a shooting incident near one of the SDF-affiliated checkpoints in the area, carried out by persons riding a motorcycle. The militant also said that the SDF patrols embarked on an arrest drive, which ended with arresting the shooters, and that they were awaiting the arrival of the director of the Asayish’s center in al-Kasra district to release the detainees. In this regard, the witness added:

“While I was in the interrogation room, a blindfolded young man was brought in. The guard of the center’s director was beating him hard, bunching and kicking the young man, while yelling at him: ‘Are you trying to get yourself killed?’ I thought that I knew the young man’s voice, and tried to sneak a peek. The guard noticed, hit me hard on the head and the shoulder and insulted me, saying: ‘keep your head down’. The young man laid on the ground for about half an hour, and was then taken to the cell by several personnel. Later, I discovered that the detainee was my neighbor. After three hours, during which we were insulted and humiliated, the director finally showed up and started asking each one of us about our names and to which tribe we belonged. With a cynical tone, he apologized and asked us to wander less at night. They released us around 12:30 a.m.”

The next day, Majed was informed that unknown persons fired at one of the SDF-affiliated checkpoints in the area, injuring one of the personnel and sending the rest into a fit of terror. Majed also said that his detained neighbor was released a week later, adding that he was subjected to beating because he refused to accompany the militants to the headquarters, as they kept humiliating him during the arrest process.

Born in Deir ez-Zor province, the second witness chose to go by the pseudonym Tayem.[14] He is married and a father of three. He was detained by the SDF for over 20 days on the charge of belonging to IS on the summer of 2018. Taken from his home at night, Tayem reported the following to JFL:

“It was around 1:00 a.m. My house was stormed without any notice. Masked personnel led me out of the bedroom in front of my family and children, who were stricken by fear. They blindfolded and stuffed me into a 4×4 car. There were other people in the car. Two militants hit me with their rifles’ butts every time I attempted to look up. They insulted me all the way around. Listening carefully to their dialect, I could make that one was Kurdish and the other was from the region. Almost 15 minutes later, the car stopped, and we were led into some place, blindfolded and handcuffed. The handcuffs were then removed, and we were placed in a four meter long and four meter wide cell, where other seven people were detained. Talking for a while, we got to know that the other men were either from western rural Deir ez-Zor or from various areas across al-Kasra district. I also got to know the people who were on the same car with me. One of them was from the al-Harmoushiya village and the other from al-Ali village.”

Inquiring into the place where he was detained, the other detainees told the witness it was the headquarters of the western countryside’s command, located in the al- Huwayej, which was a former vocational school. The witness stressed that he was not informed of the reasons for his detention, and that three days later he was taken into the interrogation room. There, a person, probably from Deir ez-Zor, according to the dialect he spoke, ordered the witness to report his personal information, asking him about his hometown and the places where he worked. The witness added:

“The interrogation went on for half an hour. I was then taken back to the cell, which looked more of a classroom. The next day, in the afternoon, the personnel once again led me to the interrogation room. There, the detective asked me the following: ‘In what region did you operate for IS?’ His question shocked me, particularly since I was one of the first people to join the peaceful protests and adopted the opposition stance to the extent that IS arrested me and subjected me to istitaba/repentance-seeking lessons 10 times. As I answered the detective that I never pledged allegiance to IS and that my stance was totally at odds with the group’s, he insisted that he had information about me, that he will help and release me only if I confessed joining IS and gave him the names of its members that I was familiar with. Having interrogated me for an hour, the detective told me he will allow me time till the next day to consider the matter, otherwise, he will be using a different interrogation method. I was returned to the cell then.”

The next day, the witness reported, he was taken to the interrogation room again, along with other people. There, his hands were tied by a robe suspended from the ceiling. In a threatening tone, the personnel told him: “This is the last time we ask, are you planning to cooperate, or shall we do it the tough way?” As he reaffirmed that he does not and had never belonged to IS, one militant hit him all over the body with a cable, while others asked him not to deny the matter. The witness was beaten for about an hour, after which he was returned to the cell, where other detainees cleaned the blood on his body that got sores due to beating. The witness said:

“The interrogation lasted for three days, and I was released about 15 days later after my family asked a tribal leader for help. The latter told them that I was detained after one of the village’s locals ratted me out saying that I was an IS affiliate. I was detained for over 20 days, during which I felt as if held captive at one of the Syrian security services’ basements. I was not harassed at all after this incident, and today I work as a teacher.”

-

Conclusion and Recommendations

International human rights instruments, in particular article 9 of both the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR),[15] and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) protect the right to personal liberty,[16] which states that: “Everyone has the right to liberty and security of person. No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest or detention.” That is no one shall be arbitrarily detained, especially since that customary International Humanitarian Law (IHL) prohibits arbitrary deprivation of liberty. Detention, which, in itself, is not a violation of human rights and can be legitimate, becomes arbitrary when the deprivation of liberty is carried out in violation of fundamental rights and guarantees set forth in relevant international human rights instruments.[17] The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (WGAD) has defined several categories under which detention is considered arbitrary:[18]

- Ø When it is impossible to invoke any legal basis for the deprivation of liberty (as when a person is kept in detention after the completion of his sentence or despite an amnesty law applicable to him/her);

- Ø When the deprivation of liberty results from the exercise of the rights or freedoms guaranteed by the UDHR and the ICCPR, such as the right to freedom of opinion and expression, peaceful assembly and association;

- Ø When international norms relating to the right to a fair trial have been totally or partially violated, for example if the person has been imprisoned without charge or denied access to a lawyer;

- Ø When the deprivation of liberty is based on discriminatory grounds such as, amongst others, on ethnic origin, religion, political or other opinion or gender.

Recommendations

- The Autonomous Administration/Syrian Democratic Forces must explain and make clear the legal basis underlying the arrests and detentions, which must also be drafted and published in language and terms intelligible to all citizens, especially when detentions are aimed at civilians and activists;

- Arrests must only be carried out by authorities bestowed the powers to do so, based on official warrants issued by the Public Prosecutor’s office or those authorized to issue such warrants;

- Detainees must be granted the right to communicate with their families and lawyers without delay, be notified of the reasons for their arrest, be ensured that they will be promptly brought before a judge, have formal charges made against them, or be released immediately;

- When charges are laid, the accused must be granted a fair trial before an independent court. However, local and international human rights organizations must be allowed to monitor trials.

-

Appendix

The table below provides the names of some currently detained persons and available information pertaining to each case:

|

Full Name |

Arrest Date |

Detention Facility |

Perpetuators |

Additional Remarks |

|

Abdulhameed al-Khalidi, born in 1974 |

25 December 2019 |

Al-Suwar Central Prison- Terrorism Ward |

The SDF-General Security Forces |

He is married and a father of four. He was arrested from his home in the Himmar al-Ali village, along with Abu Baker Jamil al-Dhraifi, as they share the same house since their wives are related. Both men’ health is deteriorating, reports indicate. |

|

Abu Baker Jamil al-Dhraifi, born in 1984 |

25 December 2019 |

Al-Suwar Central Prison- Terrorism Ward |

The SDF-General Security Forces |

He is married and a father of four. A released detainee reported that Abu Baker attempted suicide several times, and he is now suffering from a skin disease and ulcer and is denied healthcare. |

| Muhammad Walid al-Muhammad,

born in 1988 |

25 December 2019 |

Jerkin Prison |

The SDF-General Security Forces |

|

|

Knaidi Muhaimeed al-Omar, born in 1974 |

11 April 2020 |

Al-Qamishli Prison |

The SDF |

He is married and a father of seven. While originally displaced from al-Shaitat region, he was arrested from his home in the village of Himmar al-Kasra during a raid. |

|

Khalid Ammer al-Muhaimeed, born in 1991 |

August 2020 |

Al-Shadadi Prison |

The SDF- Military Police |

He is married and a father of two. He was an SDF recruit and was arrested for hitting a Kurdish commander and insulting the women of Deir ez-Zor. |

[1] HAT is an abbreviation of the Kurdish name of the Anti-Terror Forces — Hêzên Antî Teror.

[2] “Statement to the Public Opinion” (in Arabic), SDF-Media Center, 10 June 2020, https://sdf-press.com/?fbclid=IwAR3um1ny8RZQv5JKb9rlIDh9HZdA1hIZKnwSm-9cipKWySlt6DSavdLSHA0 (last visit: 14 October 2020).

[3] “Statement to the Public Opinion” (in Arabic), SDF-Media Center, 21 September 2020, https://sdf-press.com/?p=32505&fbclid=IwAR2CcK0fUPnu2CVNTSPhSN7GNEXGg8n6gbfKbaZV6GB6noCVPlaUKFeKtrQ (last visit: 14 October 2020).

[4] “Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic: Human Rights Council, Forty-fifth session” UN, 10 August 2020, https://undocs.org/en/A/HRC/45/31 (last visit: 14 October 2020)

[5] “Syria: Prominent Activists Arbitrarily Arrested in Raqqa”, STJ, 30 August 2020, https://stj-sy.org/en/syria-rising-child-abandonment-poverty-is-the-leading-cause/ (last visit: 14 October 2020).

[6] “Autonomous Administration in Northeastern Syria Releases Four Activists in Raqqa”, STJ, 30 August 2020, https://stj-sy.org/en/syria-rising-child-abandonment-poverty-is-the-leading-cause/ (last visit: 14 October 2020).

[7] “11 Syrian Organizations Strongly Condemn the Repeated Assassinations in Deir Ezzor against Tribal Leaders”, STJ, 20 August 2020, https://stj-sy.org/en/11-syrian-organizations-strongly-condemns-the-repeated-assassinations-in-deir-ezzor-against-tribal-leaders/ (last visit: 14 October 2020).

[8] The witness was interviewed online by STJ’s field researcher on 24 July 2020.

[9] The witness was interviewed online by STJ’s field researcher on 26 July 2020.

[10] Sheikh Mutasher al-Jad’an was assassinated in August 2020.

[11] The witness was interviewed online by STJ’s field researcher on 30 July 2020.

[12] Al-Kasra is a district, where a town by the same name is also located.

[13] The witness was interviewed in person by JFL’s field researcher on 11 June 2020.

[14] The witness was interviewed in person by JFL’s field researcher on 12 July 2020.

[15] “Universal Declaration of Human Rights”, UN, https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/index.html

[16] “International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights”, OHCHR, https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/ccpr.aspx

[17] “Arbitrary Detention”, AlKarama, https://www.alkarama.org/en/issues/arbitrary-detention (last visit: 14 October 2020).

[18] For further information, kindly refer to: “Working Group on Arbitrary Detention”, OHCHR, https://www.ohchr.org/en/issues/detention/pages/wgadindex.aspx