Introduction: The Court of Justice in Horan[1] issued number of arrest warrants against sixteen persons from Daraa province on the background of their participation in the "Syrian National Dialogue" Congress held in the Russian city of Sochi on January 29 and 30 2018. The persons are Bassam Omar Masalmeh, Ahmed Abdel Karim al-Mahameed, Fahad al-Adawi, Mohammed Abdel Majeed al-Labad, Abdel Aziz Alrifai, Ayman al-Aswad, Abdel Salam al-Swidan, Jamal Aqeel al-Masalmeh, Ayesh Gheneim, Ghada al-Masalmeh, Suleiman Talal al-Labad, Hussein Al-rifai, Mounir Al-Sweidan, Faisal al-Shahadat, Khaled al-Sharaa and Mutaz al-Saydali. According to the field researcher of Syrians for Truth and Justice/STJ, on January 31, 2018, lawsuits of “high treason and contact with foreign entities” were filed against them by some local bodies in Daraa.

According to several testimonies obtained by STJ in late February 2018, the military junta in Dael city arrested on February 3, 2018, both Faisal al-Shahadat and Khaled al-Sharaa for their participation in Sochi Congress . Anyway, both were released immediately after verifying their statements that the Syrian Air Force Intelligence Branch in Daraa forced them to go to the congress. Concerning the rest persons, the Court of Justice in Horan was unable to detain them until the date of the present report due to clan considerations.

First: Prosecutions Against Participants in Sochi Congress

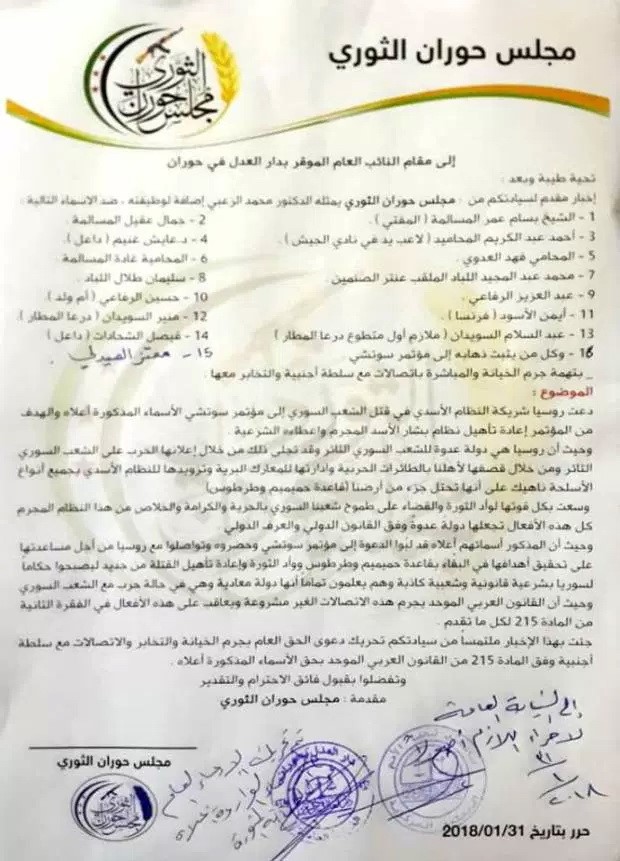

On January 31, 2018, several local bodies in Daraa, including the Horan Revolutionary Council[2], the Freemen Dael Assembly[3] and the Free Bar Association[4] prosecuted to the Court of Justice in Horan for the trial of sixteen persons from Daraa on charges of "treason" following their participation in Sochi Congress. However, the Horan Revolutionary Council, published a statement on January 31, 2018, to justify the prosecutions because those persons had met the invitation of Russia, the ally of Syrian regular forces, to attend the congress. It mentioned that the those persons answered Russia's call to attend the conference, which was described as "seeking to rehabilitate the killers to become rulers of Syria, with legality and false popularity although knowing very well that it is an enemy state, and is at a war with the Syrian people." The statement noted that the Unified Arab Penal Code[5] criminalizes such illegal contacts, and punishes such acts under article 215, para 2.[6]

Horan Revolutionary Council called for the prosecution of the Public right against those accused of "treason and contact with a foreign authority ". Mohammed al-Zoubi, Head of the Executive Office of Horan Revolutionary Council, confirmed this to STJ and said:

"We prosecuted at the Public Prosecutor Office in the Court of Justice against those persons charged of treason and contact with foreign parties. We are still collecting and confirming other identities to sue them, as we are reported that there are some wanted people in Dael in Daraa countryside, and they are currently held by factions belonging to the Syrian opposition and they will be handed over to the court. Moreover, we pursue the cause in cooperation with the Public Prosecutor Office, which has issued warrants to arrest 16 persons who participated in Sochi Congress. However, there are some impediments relating to “clan " and "zonal" reasons preventing to hold them accountable, but we seek to do the right, particularly since some of the defendants are godfathers of reconciliation with the Syrian regime and had attended Sochi Congress with their own will.”

Image of the statement issued by Horan Revolutionary Council on January 31, 2018, which called for taking actions against participants in the "Sochi" congress.

Photo credit: the page of Horan Revolutionary Council of .

Second: Inquisition with some Participants in "Sochi" Congress

Late January 2018, a civil authority in Dael, known as the " Freemen Dael Assembly" filed a lawsuit to the Court of Justice in Horan against four people from the city, specifically those who had participated in Sochi Congress. They are identified as Khaled al-Sharaa, Faisal al-Shahadat, Ayesh Gheneim and Ayman al-Asemi. On February 3, 2018, the court issued warrants to arrest them. Accordingly, the Syrian opposition factions in the city arrested both Khaled al-Sharaa and Faisal al-Shahadat, but released them later after verifying their statements that they had been forced to go to the conference by the Syrian Air Force Intelligence Branch in Daraa. In this regard, Fehmi al-Asemi, a member of the administrative body of Freemen Dael Gathering, said:

"The Assembly considers Russia to be an occupying state, and everyone who deals with the occupier and facilitates controlling our country is a spy and a traitor. Since those persons had gone with the Syrian regime delegation to the conference, consequently, they agree to the crimes being committed against civilians. Therefore, we prosecuted four persons from Dael, and, in turn, the Court of Justice sent warrants to bring them to justice. The military junta[7] affiliated to the armed opposition in Dael, summoned two of them after returning from Russia, they are identified as Faisal al-Shahadat and Khaled al-Sharaa. During the interrogation, both confirmed that the Syrian Air Force Intelligence Branch in Daraa had summoned them just a day before Sochi Congress, sent them to Damascus city, then the next morning drove them to Damascus International Airport to get on a plane travelling to Russia without passports or any other documents. Lastly, the plane took off to Russia and they attended the conference. No prior coordination to go to the conference had been done.”

Al-Asemi added that the inquisition with the mentioned persons was conducted in a “civilized way” and without any pressure, indicating that they returned to their homes following the completion of the inquisition. For the other two persons (Ayesh Gheneim who resids in Damascus and Ayman al-Asemi who resides in Turkey), their cause would be pursued through the civil courts to know why they attended the conference, al-Asemi stressed.

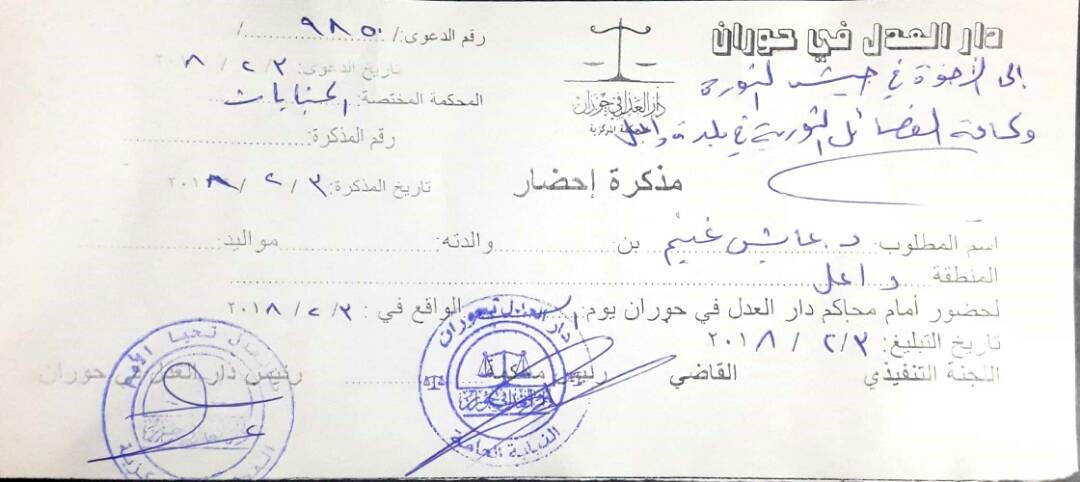

Image of the subpoena issued on February 3, 2018, by the Court of Justice in Horan against Ayesh Gheneim, one of the participants of Sochi Congress.

Photo credit: An activist from Daraa.

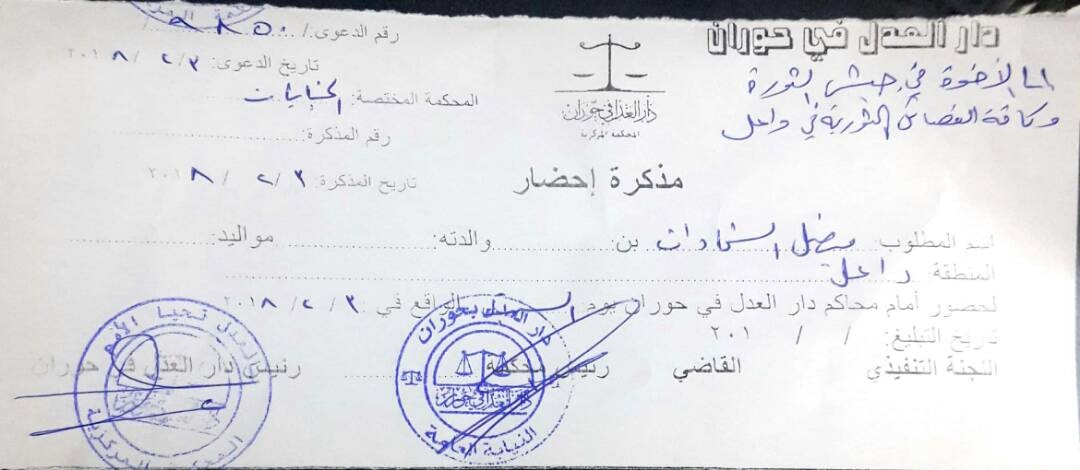

Another image shows a subpoena issued on February 3, 2018, by the Court of Justice in Horan against Faisal al-Shahadat, one of the participants of Sochi Congress.

Photo credit: An activist from Daraa.

Another image shows a subpoena issued on February 3, 2018, by the Court of Justice in Horan against Khaled al-Sharaa, one of the participants of Sochi Congress.

Photo credit: An activist of Daraa.

Third: The Court of Justice in Horan Awaits Extradition of the Accused for Investigation

The field researcher of STJ confirmed that the Court of Justice in Horan has not been able to arrest the accused persons until the time of preparing this report, except for Khaled al-Sharaa and Faisal al-Shahadat, who were released immediately on February 3, 2018, despite the issuance of arrest warrants by the Court of Justice. The majority of the "wanted persons" are in areas controlled by the Syrian opposition in Daraa province. and in this regard, Ismat al-Absi, Head of the Court of Justice in Horan told STJ,

"The Court of Justice in Horan issued several lawsuits against some people from Daraa, who had participated in Sochi Congress, on charges of treason and contact with opposed foreign parties under article 215 of the Unified Arab Law adopted by the Court of Justice. Moreover, the court has some evidences confirming these charges, which will be proofed or denied through the judiciary. The accused have the right to defend themselves in front of the court. There had been clan considerations that prevented arresting some persons within areas held by Syrian opposition but they were passed and the persons would be arrested in the coming days. It is worth mentioning that two participants in Dael were placed under house arrest until they are handed over and offered to justice, and the Court has no information of the course of investigation carried out by the military junta in Dael, and what they said there is something that is not taken into account. They are wanted by the judiciary, which will decide the case. Their excuses must be put before the Public Prosecutor Office, which will face them with evidence it possess. if it is proved that they were forced to attend the conference, then, the court would consider them not guilty."

The Supreme Body of Negotiations is the only official and authorized part to conduct the negotiations, and any other party negotiating with the "enemy", should be charged with crime and treason, so how if these negotiations take place on the territory of Russia that support the Syrian regular forces in killing innocent people!, al-Asemi said and noted that a decision had already been taken by the revolutionary and civil events of Syria to reject the Sochi Congress and its findings, in addition to consider as traitor all those who participated in it.

Fourth: The Legal Framework – Non-State Actors’ Courts

In the context of a non-international armed conflict (NIAC), international humanitarian law (IHL) does not expressly allow non-state actors to establish a court and to prosecute individuals. On the other hand, it regulates the operation of courts in the context of a NIAC.

This document first (i) establishes whether IHL can be interpreted to regulate also the establishment and the operation courts by non-state actors, second (ii) examines whether IHL provides, at least implicitly, a legal basis for the establishment of such courts and third (iii) lists the requirements which non-state actor’s courts must satisfy in order to comply with IHL.

In this document the term armed group and non-state actor will be used interchangeably.

IHL regulates the operation of courts in a NIAC in two provisions: Common Article 3 and article 6(2) of Additional Protocol II to the Geneva Conventions (AP II).

Article 3 prohibits “each party to the conflict”- state and non-state actors alike- to pass sentences and to carry out executions without “a previous judgment pronounced by a regularly constituted court affording all the judicial guarantees which are recognized as indispensable by civilized peoples”.[8] The ICRC study on Customary International Humanitarian Law suggest that a court is regularly constituted if it has been established and organized in accordance with the laws and procedures already in force in a country.[9] This interpretation would exclude the possibility for non-state actors to establish courts as it is unlikely that national laws would provide for the establishment of courts by entities other than the state.[10] The 2016 Commentary to the Geneva Conventions acknowledges that this interpretation would render the application of article 3 to “each party to the conflict” meaningless.[11] Therefore, according to the Commentary the term “regularly constituted courts” could be interpreted to include courts constituted according to the “laws” adopted by the armed group.[12]

Article 6(2) APII, drafted several years after Common Article 3, does not use the term “regularly constituted courts”, rather it prohibits the passing of sentences and the execution of penalties unless “pronounced by a court offering the essential guarantees of independence and impartiality”.[13] The requirement of independence is satisfied if the court and the individual judges are independent from the other branches of the state, or in this context from the leadership of the armed group in control of the territory. The requirement of impartiality is satisfied if the court and the individual judges do not have “preconceptions about the matter put before them”.[14]

The ICRC commentary suggests that the drafters of Additional Protocol II were aware of the difficulties deriving from the interpretation of common article 3 and decided to modify the wording into what is now article 6(2) of APII.[15] The Elements of Crimes of the International Criminal Court, a document which complements the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (Rome Statute), build on this and explain that a court would not be a regularly constituted court if it did not “afford the essential guarantees of independence and impartiality, or the court that rendered judgement did not afford all other judicial guarantees generally recognized as indispensable under international law”.[16] APII and the Elements of Crimes reinforce the argument in favour of the applicability of IHL rules to the establishment of courts by non-state armed groups as the requirements of independence and impartiality can also be met by courts of armed groups. Additional Protocol II and the Elements of Crimes are not binding on Syria as Syria is neither a party to APII nor to the Rome Statute. However, the Elements of Crimes and more importantly article 6(2) of the Additional Protocol are relevant to the interpretation of common article 3 as the Protocol “develops and supplements” common article 3.[17]

The argument according to which international humanitarian law regulates armed groups courts finds further support in the application of the doctrine of command responsibility to NIAC.[18] According to such doctrine, a military commander would be criminally responsible if he knew or had reason to know that a subordinate had committed a violation of IHL and he failed to take necessary and reasonable measures to punish the subordinate.[19] In addition, the UN Security Council in its resolution often calls all parties to the conflict to “ensure respect for international humanitarian law in all circumstances”.[20] One way of avoiding criminal responsibility and ensuring respect for IHL is to refer the individual responsible for violations of IHL to judicial authorities. However, it is unrealistic to require the commander of an armed group to refer one of his subordinates to the state authorities, thus the judicial authorities in question will have to be those of the armed group.

Against this background, it can reasonably be argued that IHL regulates the creation and operation of courts by non-state actors. This conclusion is supported by the ICRC and by good part of the doctrine.[21] On the other hand, the argument according to which IHL not only regulates, but also implicitly provides a legal basis for the establishment of armed groups courts is more controversial.[22] A recent decision by a Swedish court might shed some light in this respect.

At the beginning of 2017 a Swedish District Court ruled that non-state armed groups have the capacity under international law to establish courts and carry out penal sentences, but only under certain circumstances.[23] The case involved a member of the armed group “Firqat Suleiman el-Muqatila” who had executed a number of individuals allegedly sentenced to death following a trial before a court established by the armed group.[24] In the decision, the Court acknowledged that that the term “regularly constituted” contained in common article 3 may give the impression that only a state can establish courts. However, making reference to the Additional Protocols and their commentaries and the Elements of Crime of the International Criminal Court it found that the focus has now shifted from how a court is established to whether it upholds fundamental procedural guarantees of impartiality and independence.[25] The Court then ruled that since IHL requires armed groups to refrain from inhumane acts such as murder and torture, it also makes demands on them to maintain discipline in their own ranks.[26] Therefore, an armed group must be able to establish courts, but the legal capacity to do so is limited to i) uphold discipline in the actions of its own armed forces and ii) uphold law and order on a given territory under the condition that the court is staffed by personnel who were appointed as judges or officials in the judiciary prior to the outbreak of conflict, and that the court applies the law which was in effect before the conflict, or at least does not differ substantially in a stricter direction from the law that existed before the conflict.[27] In addition, any trial must fulfil due process standards.[28]

This decision is probably the first of a domestic or international court to address the legitimacy of courts established by non-state actors. It is perhaps excessively restrictive in setting the requirements to be satisfied by non-state courts, but it confirms an interpretation of common article 3 in line with the requirements of article 6(2) of AP II. More importantly, it supports the argument of part of the doctrine that IHL not only regulates, but also implicitly authorises armed groups to establish courts.[29] The decision of the Swedish court is not binding under international law, however it constitutes a precedent which will be taken into account by any other court dealing with a similar issue. An upcoming case before the International Criminal Court involving a former member of an armed group operating in Mali, which according to the prosecution was involved in the work of an Islamic court in Timbuktu, will probably provide more certainty on the status of international law on this issue.[30]

Finally, in order to comply with IHL, besides the necessary requirements of independence and impartiality, any trial before a non-state actor’s court must afford a number of judicial guarantees. Common article 3 does not specify what are the “judicial guarantees which are recognized as indispensable by civilized peoples”. On the other hand, article 6(2) of AP II lists a number of due process guarantees. AP II is not binding on Syria. However, the list of article 6(2) can be used as a guidance to interpret common article 3,[31] especially since the ICRC in its most recent commentary to common article 3 argued that the judicial guarantees of article 6(2) have attained customary status.[32]

There is a strong argument in favour of considering the following judicial guarantees as indispensable:

-

the obligation to inform the accused without delay of the nature and cause of the offence alleged;

-

the requirement that an accused have the necessary rights and means of defence;

-

the right not to be convicted of an offence except on the basis of individual penal responsibility;

-

the prohibition to be held guilty for an offence which did not constitute a criminal offence at the time when it was committed and the prohibition of a heavier penalty than that provided for at the time of the offence;

-

the right to be presumed innocent;

-

the right to be tried in one’s own presence;

-

the right not to be compelled to testify against oneself or to confess guilt;

-

the right to be advised of one’s judicial and other remedies and of the time-limits within which they may be exercised.[33]

In addition, according to the ICRC, although not listed by article 6(2) also the following guarantees must be complied with:

-

the right to present and examine witnesses;

-

the right to have the judgment pronounced publicly;

-

the prohibition to prosecute or punish someone more than once for the same act.[34]

Conclusion

In summary, although it is still unclear whether IHL provides a legal basis for the establishment of courts by non-state actors, according to the prevailing view, the rules of IHL regulating the establishment and operation of courts during an armed conflict apply also to courts of non-state actors. Important legal consequences derive from this interpretation.

Most notably, as long as the court of non-state actors satisfies the requirements of independence and impartiality and as long as it only passes out sentences or carries out executions whilst affording all the necessary judicial guarantees, the non-state actor responsible for the establishment of the court would not breach international humanitarian law. Moreover, the individuals involved in the work of the court would not be held criminally responsible for the war crime of “sentencing or executing without due process” ex article 8(2)(c)(iv) of the Rome Statute or, in the event of an execution carried out following a decision of such a court, to the war crime of murder ex article 8(2)(c)(i) of the Rome Statute.

Based on the details obtained by Syrian For Truth and Justice as to whether the court in Horan satisfied the requirements of independence and impartiality or whether the suspects were afforded the aforementioned judicial guarantees during the trial. It is arguably unlikely that these requirements were met. For instance, doubts could be raised about the Horan court’s compliance with the principle of legality (the prohibition to be held guilty for an offence which did not constitute a criminal offence at the time when it was committed) since it is unclear whether the suspects’ conduct constituted an offence at the time when it was committed. When applying the findings of the Swedish court above, it should be questioned whether the element ii) is satisfied, namely the Houran court needing to uphold law and order on a given territory under the condition that the court is staffed by personnel who were appointed as judges or officials in the judiciary prior to the outbreak of conflict, and that the court applies the law which was in effect before the conflict, or at least does not differ substantially in a stricter direction from the law that existed before the conflict. It must remembered however that the decision of the Swedish court is not binding under international law, but it constitutes a precedent which will be taken into account by any other court dealing with a similar issue.

If the court itself or the trials were found not to satisfy the requirements established under IHL, the non-state actor responsible for the establishment of the court would be acting in breach of IHL and the individuals involved in the work of the court could potentially be held responsible for the war crime of “sentencing or executing without due process”.[35]

[1] In November 2014, military commands and civil and relief bodies announced the formation of the Court of Justice in Horan to be the only judicial body representing the judiciary in both Daraa and Quneitra provinces, with the abolition of all other courts affiliated to the armed factions. The Court of Justice composes of several judges and is currently chaired by Ismat al-Absi. The Unified Arab Law is the reference in resolving the disputes referred to them.

[2] Its first conference was held on October 30, 2017 and consists of 300 civilian and military personalities who oppose the Syrian regime. The council represents most areas of Daraa province, and aims to create one political and military facade for Daraa to be represented at internal and external conferences, through which Board of Revolution Trustees has been formed. Board of Revolution Trustees included 48 personalities, half of them were military; Abdelhakeem al-Mesri was elected the Secretary-General of the Council, and Dr. Mohammed Zoubi the Head of the Executive Office.

[3] A civic gathering of 100 youth from the educated and national class in Dael located in Daraa countryside; founded in May 2017. The objective is to create a form of institutional organization for the civil society in Dael, which has no political orientation and does not follow any leftist, national or religious ideology.

[4] Established in December 2012 and includes nu