Introduction:

“Syrians for Truth and Justice” organization, with the support of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), facilitated and organized a number of dialogue sessions, under the title of (“The Road Towards a New Syrian Constitution: How to Benefit from the Experiences of Other Countries?”). The aim of these dialogue sessions was to informing a diverse group of Syrians about the experiences of four different countries, some of which appear to have succeeded, to a great extent, in properly addressing the issue of diversity and inclusion during their constitution-drafting process, and others whose experience were not as successful, if at all. In some of these experiences, the failure to comply with the fundamental principles of the rule of law was even a politically motivated deliberate step towards discriminately excluding certain groups and systematically depriving them of some of their fundamental rights not only as groups but also as individuals.

The idea of these dialogues came as a continuation of an earlier effort in the form of a series of meetings that started in 2020, under the title of (“Syrian Voices for an Inclusive Constitution”), which aimed at promoting a more inclusive constitutional drafting process, and ensuring the fair and proper representation of marginalized groups, communities and minorities. Subsequently, a set of papers were published in that regard. These papers respectively focused on the following themes:

- “The Formation and Responsibilities of the Syrian Constitutional Committee”

- “Syria’s Diversity Must be Defended and Supported by Law”

- “Transitional Justice and the Constitution Process in Syria”

- “Governance and Judicial Systems and the Syrian Constitution”

- “Socio-Ecological Justice and the Syrian Constitution”

In the 2021 sessions, the target groups were distributed mainly in the northeastern and western regions of Syria, considering gender and ethnic diversity – women were involved alongside men, and Kurds alongside Arabs, Yazidis, Assyrians, Armenians, Syriacs and other different ethnic groups. Emphasis was placed on individuals who had not participated in any similar meetings on constitutionalism and the constitutional drafting process in Syria.

This paper addresses Bosnia and Herzegovina constitutional experience. It is the third in a series of four such reports, approaching Iraq, Lebanon, Turkey, and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

After several fruitful discussion sessions between participants and a number of renowned academics and experts on the topic, “Syrians for Truth and Justice” has dedicated this paper to discussing the constitutional experience of Bosnia and Herzegovina (“BiH” or “Bosnia”).

The Notion of the “Constitution” as a Social Contract:

Looking at the political reality in many countries around the world and the most significant events in their history, such as wars, internal conflicts and revolutions that followed their emergence as independent states from colonial powers or after the fall of some empires, it becomes obvious that the newly forged artificial national identities in many of these countries with their current political borders does not inclusively represent all groups within their societies. As such, these identities did not reflect or conform to the desires of all the peoples residing in those regions; on the contrary, it seems that in most cases such identities exclusively reflect or represent that of the dominant majority or the most powerful group. Moreover, such an identity, be it ethnic, cultural, political or religious would often case be (forcefully) imposed on the rest of society, while attempting to erase the original identities of the other groups and minorities with the aim of assimilating them into the single national identity of the majority or the most powerful. These tyrannical behaviors would eventually lead to prolonged violent conflicts. In that regard, we are still witnessing the consequences of systematic acts or policies in the form of political movements calling for independence or civil wars.

During the past decade, there were several referendums in many regions around the world that called for a popular vote on independence and demanded the right of those peoples to self-determination, as in Catalonia, Scotland and the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, followed by severe political and economic consequences for the peoples who called for their self-determination.

Many other issues, such as the acquisition of power by certain groups and their exercise of monopoly over drawing the main features of the broader national identity and imposing it on other groups within the society, are the most common and direct roots of some of the outstanding conflicts in most of the states that were formed in the first half of the last century (including Syria, Iraq, Turkey). All these issues have constitutional dimensions that must be understood before seeking plausible solutions for them, and any proposed solutions to these issues, especially during any form of transitional justice, must include a cohesive and comprehensive constitutional treatment at the very first place.

| How did the dictatorships in Syria, Iraq and other countries come to power, and manage to rule for decades without competition? Is such an authority considered legitimate and how can we measure their legitimacy? Where does the legitimacy of power lie, where does it derive from and when is it lost? What is meant by the concept of “the rule of law” and how could it be achieved? What institutions are required? What powers and authorities such institutions could have? What is the role of the citizen and the concept of citizenship in all of this? |

The above questions were the starting points and main focus of the discussions in the dialog sessions, through which the quest was to create a deeper understanding of the concepts of “the constitution” and the legitimacy of authority,” before delving into the specific chosen constitutional experience to extract what could be benefited from or avoided in any future attempt to draft a Syrian constitution, in a way that would make it compatible with the values of the twenty first century and in full respect of the principle of the rule of law as the basis for its legitimacy.

Before comparing the constitutional experiences of the selected countries and delving into the concepts, standards, rights or freedoms contained in their constitutions, it was very useful to return to the theories and intellectual currents that were considered the origins of modern constitutionalism. To that end, the seventeenth century AD, was the most appropriate starting point to serve the desired purpose of this project.

In the second half of the seventeenth century, several social and political theories emerged, which are known nowadays as the “social contract theories”, which paved the way for the emergence of intellectual currents that had a profound impact on the concepts of power, citizenship, and legitimacy as we know them today. Among the most important of these theories are the theories of British philosophers such as Thomas Hobbes and John Locke and the French writer and philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau. The theories proposed by these philosophers were based on different assumptions about human nature and the ideal model of a society in which the relationship between individuals and the authority holding power is determined by the notion of a “social contract.” Through such an hypothetical contract the ruler’s individuals confer legitimacy over the ruler as an authority to exercise power over the society in order to safeguard the interests of the society as individuals as well as groups in the best possible way. Some of these theories established intellectual currents that inspired and contributed to the formulation of the principles of the French Revolution in 1789 as well as the American Revolution in 1765.

The Modern Notion of “Constitutions” and Constitutionalism:

The vast majority, if not all, states in the world have a so-called constitution, which is considered the supreme law in those countries. Despite the great resemblance between the connotation the term “Constitution” gives in each of these countries as well as the common understanding of the notion and what it generally entails, it may, however, vary in its forms and differ in what it actually includes from one country to another.

Often, Constitutions are formed after major events that have an impact on, or even shape, the national identity (the consideration of a group as a people). Such defining, or re-defining moments in the history of human groups marking a new beginning or a significant turning point, is also known as a “Constitutional Moment”. The best examples of these major events may be wars, such as World War I and World War II, or revolutions and independence movements, such as the French Revolution and its values, which later inspired the formation of constitutions throughout Europe, and the American Revolution, which led to independence from the dominating colonial power that was then the United Kingdom.

Contrary to popular belief, a constitution is not necessarily written or compiled into a single document, as it may be based on binding international or regional agreements as well as unwritten customs or practices. For example, the United Kingdom, whose constitutional laws have not yet been collected in a single document.

As for the majority of countries, they do actually have a constitution that has been compiled in writing into a single document. In general, such a document, with what it includes of laws and rules, is rigid and difficult to modify, and is characterized by a somewhat superior nature, as it determines the shape of the state and its system of government. Such a document includes a set of rules that govern the formulation of laws, the structure of government and its institutions, and the separation and assignment of powers within the state. In addition to the above, one of the most important functions of the constitution is to define and protect the fundamental freedoms and rights of citizens as groups and individuals.

Even in those countries that have a single document called the constitution, what these constitutions stipulate may be completely different from their counterparts in other countries in terms of the distribution of powers and the separation between them, as well as the designation of rights and duties assigned to individuals and institutions, in addition to defining the form of the state and its system of government.

Constitutional Function of Defining the Form of State and System of Government:

To know the form of the state or the system of government adopted by any state, it is self-evident to refer to the constitution of that country and simply look at how powers are distributed within the state structure. This assessment consists of the following two basic steps. First: the vertical distribution of powers and authorities between the center and the periphery of that state, thus defining the shape of the state, whether it is centralized or decentralized at all levels, such as Syria, which is considered a highly centralized state, where we see all the powers and authorities concentrated and centered in the capital, unlike the Republic of Iraq, which has adopted the federal model. Second: The distribution and horizontal separation between the basic institutions within the power structure in the state, such as the legislative, judicial and executive authorities, and the determination of the size of the powers granted to them at the expense of other of those institutions, which distinguishes the system of government, whether it is, for example, presidential such as the United States of America, or parliamentary such as the Netherlands and Canada.

Some of these constitutions attach more importance to the concept of national identity than others, and it usually appears in the form of a narrative story in its preamble, such as the Chinese constitution. In most cases, this story is the embodiment of the thought of a particular group in a position of power over other groups of the same society. Others, on the other hand, may not even contain a preamble, but rather enter directly and practically into the core of articles that stipulate basic rights, such as the Dutch constitution.

Some constitutions were keen to include articles and paragraphs that are not subject to amendment, in order to protect these constitutions from (easily) being changed during political fluctuations as a natural response to their historical experiences, as in the German constitution. As such, the German Constitution stipulates in the third provision of Article 79 that it is not allowed to submit or accept any amendment to those articles of the Constitution related to the federation of the German state as a union and the right of the states to participate in the legislative process. Accordingly, it may be necessary at times for these constitutions to show rigidity as a form of protection for some basic concepts and principles from changing easily, but it may also be used to perpetuate the authority of a person or a particular group or racist or discriminatory concepts against minorities, groups and other individuals within their societies, which may even cause conflicts in the future due to social, cultural or political changes. Herein lies the importance of our awareness of the sensitivity and difficulty of drafting or amending a document such as the constitution of a country so as to include a more inclusive and more just concept of citizenship, which would be primarily based on equality and respect for others under the principles of the rule of law, not only for the time of drafting but also capable of remaining remain valid and viable in the future.

Background on Bosnia and Herzegovina:

Bosnia and Herzegovina (“BiH” or “Bosnia”) is located in the Balkans region of Southeast Europe. In 2020, the population was just over 3.2 million people.[1] BiH is made up of three major ethnic groups, uniquely referred to as “constituent peoples” in the constitution; Bosniaks (~50%), Serbs (~30%) and Croats (~15%). The remainder of peoples are regional ethnic groups such as ethnic Jews and Roma.[2] The country’s major religions are divided along ethnic lines; Bosniaks are primarily Muslim, Serbs primarily Orthodox Christians, and Croats primarily Catholic Christians.

The region now known as Bosnia and Herzegovina has come under occupation several times throughout its history. It was under the Ottoman Empire from the 15th to the late 19th Century. After which, the region came under the control of the Austro-Hungarian Empire up through World War I. After the First World War, BiH joined with other nearby regions to create the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Ethnic violence between the regions’ major ethnic groups were periodic and when BiH came under Nazi occupation during WW2, the systematic extermination of Serbs, Jews and Romani would impose a collective memory on Serbs that would have future implications on ethnic tensions. That said, ethnic tensions were largely tampered throughout the Cold War as the groups were bound together under a singular republic of Yugoslavia. However, as nationalist leaders took hold of the country in the 1980s, once again the flames of ethnic divides were fanned. In the late 80’s, independence movements in the Balkans gained steam, first with Slovenia and Croatia. As the former Yugoslavia began to break down in the 1990’s, so too did tolerance.

Bosnian War of 1992-1995:

In Bosnia, the separatist movement was largely led by Bosniaks seeking reprieve from increased ethnic discrimination under Yugoslavia. The creation of an independent Bosnian nation was opposed by Serbs in the region, who would become the minority and lose the power they wielded as a republic of Serb-controlled Yugoslavia. As Bosniaks vied for independence, Serbs quickly sought to establish Serb Autonomous Regions within Bosnia while the Croats explored their own partitioning. However, before a partition could be established, a referendum was held (with obstruction of voting in Serb-populated areas) and on March 3, 1992, the government of Bosnia declared independence from Yugoslavia. As a response, a military campaign backed by the Yugoslav army was launched to secure Serb territory in the region. A similar series of events involving Serb military intervention was playing out in other regions of the Balkans in newly independent States, though to varying outcomes. The outcome in Bosnia and Herzegovina, however, would be the most atrocious war in Europe since the Nazi’s.

To secure an Autonomous Region for itself, Serb forces targeted entire villages of Bosniaks and Croatians within their desired territories, pushing out civilians by force, violence, and murder. The atrocities that would ensue amounted to ethnic cleansing. Concentration camps, mass execution sites, rape as a form of warfare and other grave violations were carried out. As news of the atrocities of the Bosnian War became apparent to the international community, NATO would begin to intervene by shot down Bosnian Serb aircrafts violating UN-imposed no-fly zone over the country, launch airstrikes against Bosnian Serb targets, while the UN declared “safe zones” for Bosniaks in parts of the country to seek refuge. Increased NATO air strikes and a Bosniak-Croat consortium force would ultimately bring the Bosnian Serbs to peace talks.

Dayton Accords and the 1995 Constitution:

Image (1): Signing of Dayton Accords by Presidents of Serbia, Croatia and Bosnia PC: Peter Turnley/ Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

After years of failed peace talk attempts all parties agreed to discuss a path to peace in 1995. The final talks were led by the U.S. at the Dayton Air Force Base. The outcome of which would be a peace agreement as well as a full constitution for BiH. The United States was the driving force at Dayton, often controlling the drafting process while consulting a team of international actors. Balancing the demands of the Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats in their vision for power sharing and self-interested demands with international goals would lead to the creation of a unique constitution. Unlike in Kosovo, the constitutional drafting process included no public involvement.

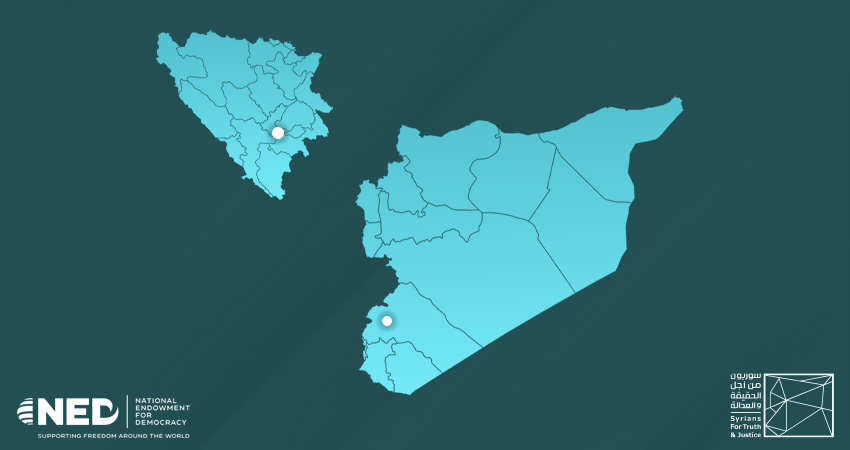

Image (2): BiH Regions, PC: U. Texas Library

Additionally, the final draft reflects the ethnic tensions and fierce mistrust in power sharing.[3] From the 1995 constitution, the country’s government was established as a decentralized State composed of two autonomous entities, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the Republika Srpska. These entities are based on the territories held by ethnic majorities at the end of the war; the Federation is majority Bosniaks and Republika is majority Serb. Nearly all of the government functions at the Entity level or lower while a group of three “Council of Ministers” with an ethnically rotating “Chair” take the role of president and prime minister to make up the central government of the country. The configuration of BiH’s regions, government structure, and civil engagement established here are highly ethnically conscious and a direct result of the context in which it was formed, that is in the wake of the ethnically-rooted Bosnian War. However, as the tensions quiet, questions of the applicability of such an ethnically divided constitution continue to be raised.

Syria’s military intelligence service.” As a result, Lahoud was granted another term by the Lebanese parliament under pressure from Syria.[4]

Many Failed Constitutional Reform Attempts, 1 Small Amendment:

As BiH seeks to integrate into European institutions, its constitution has proven a hurdle needing to be overhauled. The weakness of the central government and gaps in legislative and civic participation processes have hindered BiH in establishing their “democratic legitimacy”.[5] Entry into the EU, for example, has become contingent on an updated Constitution that aligns with regional human rights treaties and mechanisms, a more centralized state and a move away from institutions of ethnic division. Several attempts to amend the constitution to bring it into alignment with constitutions of other European countries and regional membership requirements have largely failed due to disagreement across the two Entities. Frequent critic calls on the two Entity situations be abolished or drastically reformed to establish a cohesive central State capable of conducting business with the international community without burdensome (and fragile) two Entity bureaucracy.

In 2009, U.S.- and E.U.-led constitutional reform talks failed while the European Court of High Rights (“ECHR”), a regional human rights mechanism, ruled the Bosnian Constitution breached the European Convention on Human Rights, a treaty explicitly undersigned in the constitution, because it excluded minority ethnic groups and cross-entity members from top government positions.[6] Similar cases followed yet as of 2021, the constitution has not been amended on any of the key points of the ruling, nor the E.U. has outlined in their membership requirements for BiH.

One small amendment was made in 2009 to incorporate the Brcko District, a small northeastern region technically under both entities but governs itself independently, into the Constitution, ensuring its access to the constitutional court, the highest court in BiH, to the District.[7]

International Justice: International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY):

During the Bosnian War, about 80% of those killed were Bosniaks by Serbs.[8] The death toll of the war is said to be about 100,000 while more than two million were displaced. And though the conflict began a three party civil war by which Serbs were the primary perpetrator, Bosniaks the primary victim and Croats among both victims and perpetrators, evidence of the nearly four year war has found war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by all sides.

As with the constitution, the international community played a major role in post-conflict justice in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In 1993, the United Nations established the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (“ICTY”) in response to the mass atrocities taking place. The goal was to prosecute those most responsible for acts of genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity in the Balkans. The ICTY was the first international tribunal in Europe to try perpetrators for grave breaches of international law. Most notable to be tried, were the former Serbian President,

Slobodan Milošević, former president of Republika Srpska, Radovan Karadžić, and former commander of the Bosnian Serb Army, Ratko Mladić. Though the most notable cases were Serb, the ICTY tried and convicted perpetrators on all sides of the war.

Image (3): Mirsada Malagic, witness at ICTY, on the Srebrenica massacres. PC: ICTY

Since the Dayton Agreement came after the establishment of the ICTY, constitutional provisions relating to the Court were implemented. As such, the Constitution requires cooperation of authorities with the ICTY.[9] Under Article IX of the Bosnian Constitution, no person under indictment who failed to appear or currently serving a sentence imposed by the ICTY may stand as a candidate or hold any public office in BiH. Notably missing is the provision that individuals convicted of crimes in the ICTY be barred from holding official office. In fact, there are instances of those tried and convicted in the ICTY returning to BiH to take up positions within the government.[10]

Internationally, the ICTY became a model for transitional justice mechanisms to follow. However, within Bosnia and Herzegovina, opinions on the legacy of the Court and its impact on domestic peace and justice remain disputed.

How to Benefit from the Experience of Bosnia and Herzegovina:

In the dialogue session on the experience of Bosnia and Herzegovina, participants agreed that despite the latters similarities to the Syrian experience, it differs in several aspects that must be taken into account.

According to participants, the type and severity of the crimes committed in Bosnia and Herzegovina are very similar to what is being committed in Syria. However, the Bosnian society lacked trust between population groups, which must be avoided in Syria as it is very important to accept the idea of coexistence. Moreover, the people of Bosnia and Herzegovina speak one common language (that may vary slightly from place to another). Further, Bosnia and Herzegovina does not have a problem in distributing national wealth (especially oil). Also, Bosnia and Herzegovina does not have a centralized military system and the security and police forces work at the local level.

On the other hand, while Syria considers itself one nation, Bosnia and Herzegovina is a country of several societies and populations. Also, its location close to Western countries led to their greater intervention during the war. Finally, unlike Syria, in Bosnia and Herzegovina there is no totalitarian regime.

Regarding the importance of the transitional period to reach a sustainable solution in Syria, the participants agreed that it is an inevitable phase and a necessary element in the path of justice as it is not possible to reach sustainable peace without accountability.

Furthermore, participants mentioned that the Dayton Accords focused on political rights and the protection of the three ethnic groups that signed the agreement (which granted their right to veto that subsequently disrupted political life).

During the session, the participants discussed how constitutions are usually adopted in response to national circumstances and needs. However, the 1995 constitution was a part of the peace process adopted after several peace plans of the international community. It was not the result of the participation of Bosnian parties and politicians. Rather, some Bosnian elites and neighboring countries participated in the process, as well as the Western countries.

According to the discussions, this constitution did not aim to build a State that achieves justice and equality for citizens, but rather to keep the situation as it was. In addition, the constitution created a conflict between the rights of individuals and ethnic groups. It caused great tension between different ethnic groups because they were not taken into account when dividing areas between local communities.

Finally, the participants stressed the need to find a balance between the role of the international community and State sovereignty. Some of them emphasized that the Syrian political reality requires the presence of international parties because many of the latters are part of the current problem, and therefore, as in the Bosnian experience, they can have a key role in the success of the political process. However, that should not detract from national sovereignty.

Recommendations:

- To ensure that the individual status of population groups is not given priority at the expense of national identity.

- The Syrian constitution should be based on diversity and pluralism and not be bound by nationalism or ideology.

- To involve everyone in the Syrian political process and in writing the constitution, and ensure that democracy is not eliminated.

- To develop the cultural and cognitive level of all population components in Syria.

[1] World Bank, 2020 Population Data.

[2] 2013 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

[3] Framing the State in Times of Transition, Miller, Laurel E. and Aucoin, Louis, 2010, United States Institute of Peace Press

[4] “Lebanon – Politics – 2004-8,” Global Security, https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/lebanon/politics-2004.htm.

[5] Venice Commission, Opinion of the Constitutional Situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Powers of the High Representative, CDL-AD (2005) 004, 11 March 2005, para. 64.

[6] Sejdić and Finci v. Bosnia and Herzegovina, ECtHR, Judgement, 27996/06 and 34836/06, 22 December 2009.

[7] Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina 1995 (rev. 2009), Art. VI §4.

[8] United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, “Bosnia and Herzegovina, 1992-1995” and “Serbian Forces Target Civilians, available at https://www.ushmm.org/genocide-prevention/countries/bosnia-herzegovina/case-study/background/1992-1995.

[9] Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina 1995 (rev. 2009), Art. II §8.

[10] Balkans Insight, “Balkan War Crime Suspects Maintain Political Influence”, 7 December 2016, available at https://balkaninsight.com/2016/12/07/balkan-war-crime-suspects-maintain-political-influence-12-02-2016/.