Background

26th June of each year marks the International Day in Support of Victims of Torture. The General Assembly, in the resolution 52/149, December 12, 1997, proclaimed an International day for support for victims of torture with a view to total elimination of torture and effective functioning of the Convention against Torture, and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.

Torture is a crime under international law. It is strictly prohibited by all relevant instruments and cannot be justified under any circumstances. It is a prohibition that forms part of Customary International Law, which means that every member of the international community is abided, without regard to whether it has ratified or not ratified the international treaties that explicitly prohibit torture. The systematic and widespread practice of torture constitutes a crime against humanity.

With the beginning of the protests in Syria in March 2011, the Syrian government and its security agencies began arresting tens of thousands of demonstrators randomly. Although most of the arrests in the first months of the uprising were less severe than the months and years later, the overwhelming proportion of detainees were subjected to systematic ill-treatment and torture within Syrian secret and public detention facilities, before other agencies, which are different from the Syrian security sector, joined those who insult, strike and torture detainees in Syria.

The Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Syria, established in August 2011, issued an extensive report on systematic torture in Syria in February 2016, entitled "Out of Sight, Out of Mind… Deaths in Detention in the Syrian Arab Republic" it detailed how detainees by the Syrian government were beaten to death or died as a result of injuries sustained due to torture. Many other detainees perished as a consequence of inhumane living conditions. The report determined that the government of Syria had further committed the crimes against humanity of murder, rape or other forms of sexual violence, torture, imprisonment, enforced disappearance and other inhumane acts. These violations constitute war crimes.

Several international organizations had issued dozens of reports about the horrors of places of detention, torture and killings to which detainees are subjected in Syria. In December 2015, Human Rights Watch/HRW issued a report entitled "If the Dead Could Speak… Mass Deaths and Torture in Syria’s Detention Facilities" a report reveals the stories of some of the victims who died in Syrian government custody and appeared in the images of the defector, code-named “Caesar”. The nine-month research by HRW documents names of the victims and their appalling conditions of detention, through interviews with former detainees, defectors and relatives of victims, as well as forensic techniques and geographic positioning.

The legal framework:

First: Relevant international laws:

1. International Human Rights Law:

International human rights law is applicable in peacetime and some cases in wartime. Although many differ about what are the human rights applicable in wartime, the prohibition of torture is applicable both in times of peace and during war. Here are the most important conventions with regard to the prohibition of torture:

Article 1 of Convention against Torture adopted by the General Assembly in its resolution 39/46 on December 10, 1984; defines the term of torture as following:

"Any act resulting by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or suspected of having committed, or intimidating, coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at investigation of or with the consents or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity."

The Convention also seeks states to prohibit any further acts of cruel, inhuman, degrading treatment or punishment that does not amount to torture.

The Convention is also one of the most signed agreements, with 144 States parties, including Syria that signed the Convention in 2004 with reservations to one of the articles/items in the Convention.

B. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

Article 7 of The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights adopted on December 16, 1966, affirms that no one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading Treatment or punishment. Article 10, reiterates that all persons deprived of their liberty shall be treated with humanity. The Covenant is the first universal human rights treaty that explicitly prohibits torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading Treatment or punishment.

C. Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights– although it was a non-binding declaration- was the first in the discourse on the prohibition of torture. Article 5 states that no one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading Treatment or punishment.

D. Arab Charter on Human Rights

The Arab Charter on Human Rights of 2004 prohibits torture, both physical and psychological. It states in its article 8, as follows:

1. No one to be shall subjected to physical or psychological torture or to cruel, inhumane or degrading treatment.

2. Each State party shall protect every individual subject to its jurisdiction from such practices and shall take effective measures to prevent them. The commission of, or participation in, such acts shall be regarded as crimes that are punishable by law and not subject to any statute of limitations. Each State party shall guarantee in its legal system redress for any victim of torture and the right to rehabilitation and compensation..

2. International Humanitarian Law:

International humanitarian law applies to international and non-international armed conflicts (such as those in Syria). This law is binding on all States parties to the conflict, whether they signed to the relevant conventions or not. This is due to the fact that international humanitarian law is considered to be part of Customary Law, which is a source of international law, according to article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice.

In non-international conflicts such as those in Syria, torture is prohibited under the common article III of the four Geneva Conventions which are the most important conventions on international humanitarian law.

According to the study of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in customary law “Torture, cruel or inhuman treatment, and outrages upon personal dignity, in particular, humiliating and degrading treatment are prohibited” (Rule 90). It should be noted that torture is prohibited against civilians and combatants alike.

According to rule 152 of the ICRC study, the responsibility for the acts is not only of those who commit acts torture, but also of the leaders who ordered the commission of such acts. Rule 153 builds on the previous rule and adds:

"Commanders and other superiors are criminally responsible for war crimes committed by their subordinates if they knew, or had reason to know, that the subordinates were about to commit or were committing such crimes and did not take all necessary and reasonable measures in their power to prevent their commission, or if such crimes had been committed, to punish the persons responsible”.

Finally, according to rule 154 “every combatant has a duty to disobey a manifestly unlawful order” such as torture.

3- Secuirty Council Resoluations

Many Security Council resolutions have also condemned torture. In the Syrian context resolutions 2193, 2332 and 2258 condemned torture in a strong and rigorous language.

Second: Torture and the Prohibition of Refoulment:

In addition to criminalizing torture, international human rights law prohibits states from returning persons to States where they may be subjected to torture. Article 3(1) of the Convention against Torture clarifies that:

“No State Party shall expel, return (“refouler”) or extradite a person to another State where there are substantial grounds for believing that he would be in danger of being subjected to torture.”

Third: Torture and International Courts

The most prominent international criminal tribunals, such as the International Criminal Court, the International Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and the International tribunal for Rwanda all criminalize torture. Articles 7 and 8 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court classify torture as a war crime, or a crime against humanity if committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against the civilian population.

Here again, it must be emphasized that not only those who torture are responsible for the act. Article 28(a) of the Rome Statute, regulating the responsibility of leaders and other superiors, reads as follows:

“A military commander or person effectively acting as a military commander shall be criminally responsible for crimes within the jurisdiction of the Court committed by forces under his or her effective command and control, or effective authority and control as the case may be, as a result of his or her failure to exercise control properly over such forces, where:”

A) That military Commander or person either knew, or owing circumstances at the time, should have known that the forces are committing or are about to commit such crimes; and

B) That military commander or person failed to take all necessary and reasonable measures within their power to prevent or repress their commission or to submit the matter to the competent authorities for investigation and prosecution.

Fourth: Torture and Universal Jurisdiction:

Universal jurisdiction means that national courts of some States accept jurisdiction over crimes that have not been committed within their territory. The Convention against Torture obliges States parties to exercise their jurisdiction over a person suspected of having committed torture, or to extradite that person to a state where he will be tried. The Committee against Torture has increasingly focused on this issue in its discussions with States parties, and now regularly adds in its observations concluding recommendation calling on States parties that have not yet done so to introduce legislation providing for universal jurisdiction for the crime of torture[1].

In the Syrian context, a former opposition combatant was tried in Sweden for torturing one of the detained fighters in Syria, which shows that torture even against combatants is forbidden.

In addition, the offence of torture cannot be extinguished by a general amnesty law as reflected in the judgment of a French court in a case involving a Mauritanian combatant.

Fifth: The Role of the Trust Fund for victims in international law

Both the United Nations Convention against Torture and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights impose an obligation on States parties to provide reparation to victims of torture or ill-treatment.

1. Convention against Torture (CAT): Article 14 of the Convention against Torture states that:

“Each State Party shall ensure in its legal system that the victim of an act of torture obtains redress and has an enforceable right to fair and adequate compensation, including the means as full rehabilitation as possible. In the event of the death of the victim as a result of an act of torture, his dependents shall be entitled to compensation”.

2. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights: Article 2(3) states:

Each State party to the present Covenant undertakes:

1. To ensure any person whose rights or freedoms as herein recognized are violated shall have an effective remedy, notwithstanding that the violation has been committed by persons acting in an official capacity;

2. To ensure that any person claiming such a remedy shall have his right thereto determined remedy by a competent judicial, administrative or legislative authority, or by any other competent authority provided for by the legal system of the State, and to develop the possibilities of judicial remedy;

3. To ensure that the competent authorities shall enforce such remedies when granted.

Introduction

The file of arbitrary arrest, enforced disappearance, torture and murder in detention facilities has become one of the most important and significant files left by the Syrian armed conflict. The Syrian as well as international rights-based organizations and some UN organs have estimated the number of citizens who have been arrested since 2011 in tens of thousands, possibly in hundreds of thousands. However, there is no precise statistic for the numbers of the categories mentioned, nor for all those who stand behind these violations, which has complicated the file greater, especially after the emergence of other parties during the past six years of conflict. The all estimates point to the responsibility of the Syrian government and its security apparatus that carried out the largest proportion of arrests, enforced disappearances and torture. On the other side, there are similar violations committed "even in less numbers" by other parties such as extremist Islamist organizations like Hayat Tahrir al-Sham and the Islamic State organization (ISIS), formerly al-Nusra Front, in addition to armed factions affiliated to the Syrian opposition. Apart from documenting cases of arbitrary arrests by the security apparatus affiliated to the Autonomous Administration in northern Syria, particularly the Asayesh forces.

The report sheds the lights deeply on the suffering of detainees, enforced disappeared and the tortured in particular after their release. Despite shedding light on the practices committed against detainees inside detention facilities and reasons of the arrest, the report will also tell accounts of the survivors and will focus on the physical, mental, economic and social effects, as well as the efforts made to support them mentally or physically.

Methodology and Challenges

The report-based team interviewed more than 15 detainees along with interviewing several organs designated to support survivors of the detention physically or mentally, as well as numbers of experts aware of arbitrary arrest and torture in Syria, in addition to an international legal expert. In terms of choosing the survivors, the team attempted to take into account the standards of diversity and difference whether geographically or chronologically, or according to the part that committed the violation, all of these contributed to enrich the report. However, the team faced many other challenges, including, but not limited to, the difficulty of reaching a larger number of survivors from detention facilities, for reasons that cannot be mentioned now, in addition to the difficulty of communicating with many parts scattered in the neighboring countries that work to provide physical or mental support to the survivors.

On the anniversary of the International Day in Support of Victims of Torture, the report attempts to shed light on their suffering, which lasts for many months, perhaps for years, after the end of the detention experience. We will include some of the team's recommendations at the end of the report, as well as some findings and conclusions.

First: The Effect of Torture on the Victims

The effects of arbitrary detention in Syria vary, as well as the accompanying serious violations, such as deprivation of liberty, torture and enforced disappearance, starvation, denial of health care and other violations. In many cases, these effects are not confined to the detainee himself, but to the surrounding environment, whether his family or society as a whole, and in the following paragraphs we will try to include some effects of the arrest that the survivors agreed to talk about.

A-The Physical Impact of Detention and Torture

The effect of physical torture on detainees is usually clearer than psychological torture, given the brutal methods of torture inflicted on detainees during the detention. Although most beatings and torture against detainees occur in the early hours of their arrest and in the first days of detention during interrogations and the attempts to pull a confession by coercion, many detainees told STJ about several detention facilities where physical torture was ongoing even after the end of the interrogation period.

Ahmed, a pseudonym of a survivor who refused to disclose his identity for security purposes, said in his testimony to STJ that some traces of torture still exist on his body, the torture he was subjected to during his detention at Tadmor Military Prison in Homs province in 2012. Ahmed indicated that there was a hernia in the diaphragm, stomach and esophagus, as well as other respiratory problems as a result of torture. He added:

"I still have problems in the memory and breathing that prevent me from running currently and cause severe stress while climbing the stairs; unfortunately, I have not received any financial, health or psychological support after my release neither in Syria nor in the neighboring countries."

Ahmed Samir, another former detainee who spoke in his testimony to STJ about his first arrest in 2011 and his second arrest in 2012. Ahmad spoke of the involvement of Jamea Jamea, the Head of the Military Security Branch in Deir az-Zor personally in the strikes and torture, saying:

"Jamea Jamea, the Head of the Branch personally supervised the torture process, and then participated directly when he beat me and broke all my lower teeth with his fist."

The second arrest of Ahmed was by the Air Intelligence Sector in Damascus in September 2012, before being transferred to Sednaya Military Prison. According to Ahmed, the torture in Sednaya Military Prison was carried out on a daily basis and without reason, i.e. there was no interrogation or investigation during the beatings. Ahmed described the "Confession Chair" as a method of torture:

"I was beaten, electrocuted more than once, but the Confession Chair was "special", as it is a chair with animated hinges on the back of the chair where the detainee sits on. During beatings and forced confessions, the back of the chair comes back and the detainee feels that his back is being broken, I still have pain in my back so far."

The "Confession Chair" that the witness Ahmed spoke about in his testimony is similar to the "German Chair", which is turned around the body of the detainee in reverse so that the back of the head becomes closer to the feet and causes terrible pains that may lead in many times to a fracture of the spine.

Another expressive image illustrates the method of torture called the "German Chair". Although there are multiple testimonies on how to put the chair, all the testimonies confirmed that the primary objective is to invert the detainee's body (headed down towards the feet), which constitutes unimaginable pain in addition to severe bodily harm, which may sometimes cause fractures in the vertebrae.

Ahmad spoke about other torture traces left over his body that he still suffers from, he said:

"There are several traces of torture on my body that are still clear, as I am still suffering from damage to the left kidney, and so far I am suffering from some blood coming down during the process of urinating. Let alone losing my lower teeth and a permanent pain in the back. All these effects require attention as well as health and medical care."

Image provided by Ahmad Sameer, a former detainee, illustrates some of torture traces over his body; this photo was taken months after his release. He was released in December 2013.

Photo credit: STJ

Ammar, a pseudonym of a former detainee who was arrested by the Syrian Security Apparatus three times. The first time was for nine days in 2011, the second arrest was for 11 days in 2012, and the third- which was the longest- lasted for 11 months in 2015. The Security Branches where Ammar was moved during his detention were:

-

The Criminal Security Department in Damascus, Bab Musalla Square.

-

Palestine Branch in Damascus, also known as the Branch 235, virtually affiliated to the Department of Military Intelligence (Military Security)

-

The Political Security Directorate in Damascus countryside.

Ammar summarized the arrest experiences he has undergone:

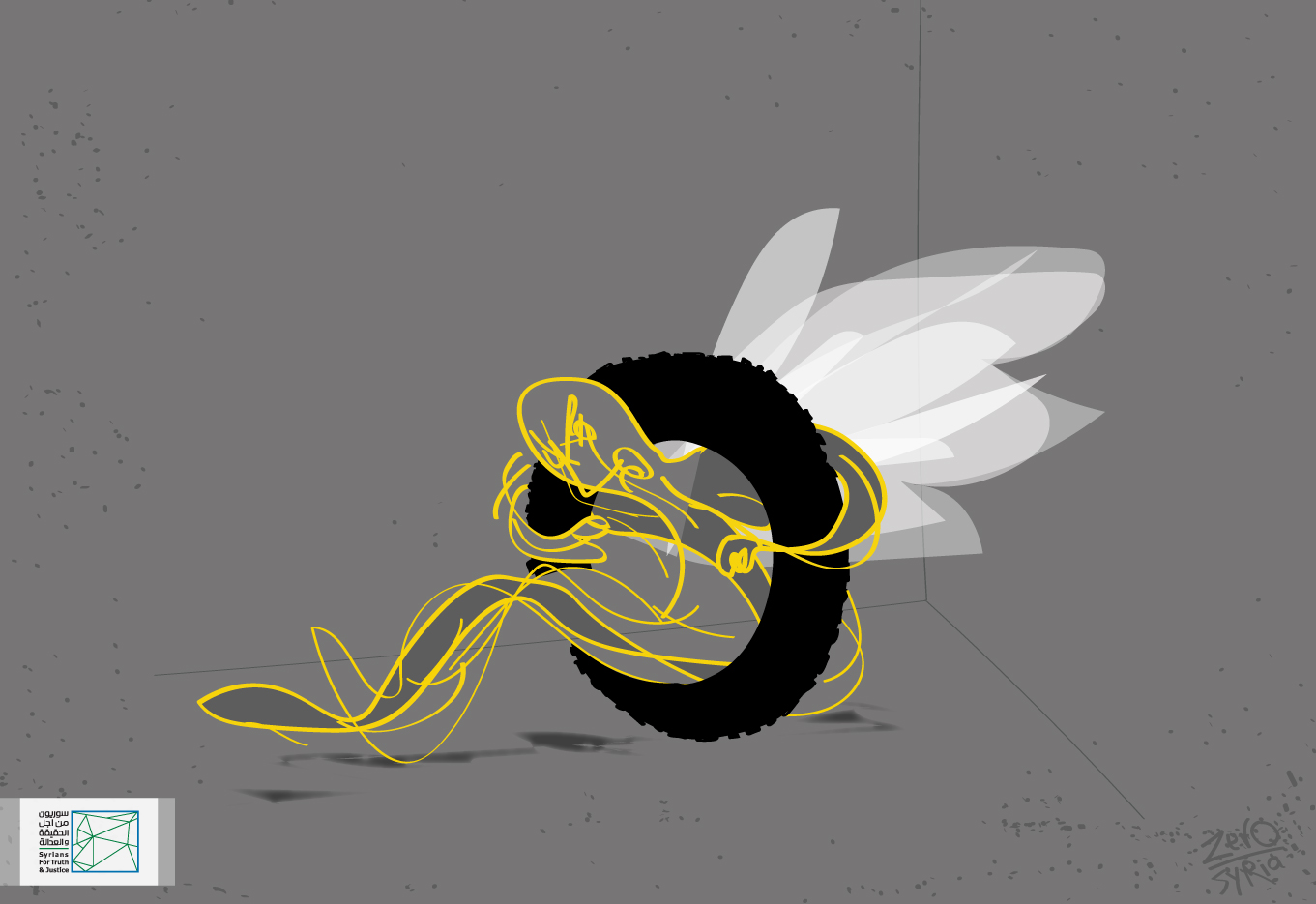

"I suffered from hardships of arrest and torture in the three detention experiences, having been subjected to numerous practices of torture, humiliation and beatings. Methods of torture varied between the "dulab/tyre technique" and extinguishing of cigarette on my body. The most painful thing was the issue of insult; as many methods were inflicted on us, such as long-term incarceration in toilets, and the bad languages they used to inflict on us. Besides, they forced me to sign on false confessions, including being the head of an Islamic militant group, although I am a peaceful secular civil activist and this charge was one of the biggest charges being directed at me and tortured me the most.”

Ammar's arrest left no permanent disability, but left some traces on his body, such as burning with cigarette butts and wounds, according to Ammar, they are still a reminder of his detention until this day.

"Tire technique" is one of the methods of torture used in various basements of the Syrian Security Apparatus, where the detainee is placed in an empty wheel and the process of investigation begins with a large amount of insults and beatings all over the body by various means such as whips, sticks and electrocution. When the detainee is put in the tire, he becomes unable to make any movement or act.

Loss/underweight in large quantities is also a prevalent phenomenon among detainees due to starvation and the small amount of food that was provided to them, all those interviewed in this report confirmed that they lost weight depending on the length of the detention.

Mohammed, an alias of one of the detainees who was arrested in 2013, by the Military Intelligence Service, Branch 215, also known as the Raid Squad, located on 6 Ayar Street, Damascus. He spoke about his experience, saying:

"I lost 14 kilograms of my weight during the arrest, and I was suffering too much from scabies that spread throughout my body with the appearance of skin stains. After my release, it took 10 days to be treated with the help of a dermatologist, but the effects of cigarette butts and skin stains are still apparent on my body to date.