In late September 2023, the External Relations Officer of the Syrian Interim Government (SIG), Yasser Mustafa al-Hajji, filed a lawsuit with the Office of the Public Prosecutor in Mare’ city against lawyer Muhammad Abdulhamid al-Mahloul. The case was met with large-scale condemnation, interpreted as a repressive practice by the SIG against legal professionals, media workers, activists, and locals in the areas it predominates.

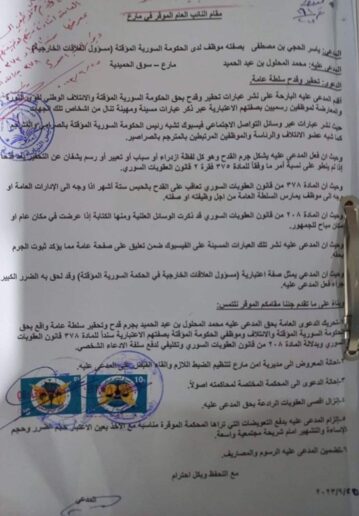

The SIG official accused lawyer al-Mahloul of “posting insulting and disparaging expressions against the SIG and the National Coalition (Also known as the Syrian Opposition Coalition-SOC).” A leaked image of the claim filed with the public prosecutor was circulated on social media. According to the claim, the “accused” commented on a Facebook post, using “abusive and invective phrases” that undermined the prestige of the SIG, as well as members and employees of the SOC. Al-Hajji labeled the comment as the crime of “insult and contempt to public authorities” based on the definition of libel in Article 375 of the Syrian Penal Code.

Al-Hajji also deemed the “offender’s” online remarks worth filing a complaint with the Mare’ Directorate of Security and initiating criminal proceedings against him, necessary to prosecute and subject him to the maximum penalties prescribed by Article 378 of the Syrian Penal Code, which references Article 208 in the same code.

To corroborate the incident and understand its context, Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) reached out to both the offender, al-Mahloul, and the claimant, al-Hajji, discovering that the latter had indeed made a motion to open proceedings against the lawyer.

In addition to the two parties to the claim, STJ interviewed two lawyers, a female media worker, and a local from the area and discussed the lawsuit brought against al-Mahloul and the status of freedom of opinion and expression in northwestern Syria—the entirety of which is controlled by the SIG and affiliated armed opposition groups.

Statements of the Involved Parties

Interviewed on 11 October 2023, lawyer al-Mahloul told STJ that neither the SIG nor the Public Prosecutor have reached out to him regarding the lawsuit, stressing that:

“This is not the first time I have been harassed. I am convinced that those who started the legal proceedings hold a personal grudge against me. [They are] trying to impede my work, possibly because I am displaced from Ma’arat al-Nu’man [in Idlib] to Mare’ [in Aleppo].”

For his part, the claimant, al-Hajji, told STJ:

“The head of the SIG and its members must not be insulted by individuals with personal or tendentious agendas or those who seek to undermine [people’s] trust in legitimate institutions. This harms public interests and disrupts security and stability. The lawsuit is important because it displays the SIG’s respect for the law and that it applies to all offenders, given that the SIG does not warrant impunity or the political misuse of freedom of expression. Freedom of expression is a legitimate right. However, it should not be used as a cover for defaming individuals or the authorities. Freedom of speech also commands a sense of responsibility and respect. For that reason, we demanded the enforcement of penalties stipulated in the penal code.”

Image 1-The motion for initiating legal proceedings against lawyer Muhammad al-Mahloul.

Judicial Independence is a Safeguard for Freedom of Expression

There is an administrative and military hierarchy in northwestern Syria, which influences the autonomy of the judiciary. Administratively, the SIG operates under the mantel of the SOC through several ministries, including the ministries of defense and justice. Militarily, numerous Turkish-backed armed opposition groups operate under the flag of the Syrian National Army (SNA). The SNA, in turn, functions under the SIG’s defense ministry.

On the ground, however, it is not the defense ministry that maintains effective control; it is the armed groups. Additionally, the Turkish government, not the justice ministry, is in charge of the legal matters where these groups operate, as the report’s interviewees told STJ.

Working in northwestern Syria, lawyer Fahd al-Mousa, head of the Syrian Commission for Releasing Detainees, disputed the status attributed to the SIG as a public, legitimate, elected representative authority of the Syrian people, and hence the legality of the case filed against al-Mahloul. The case is hinged on Articles 375 and 378 of the Syrian Penal Code, which are concerned with slander, libel, and contempt for a public authority. He said:

“The crime of slander, libel, and contempt must be committed against an official entity or a public servant, according to the articles referenced in the case. However, the SIG is neither elected, legitimate, nor officially recognized.”

He explained that the Syrian Penal Code grants the judge the power to vindicate or condemn a defendant in a “slander, libel, and contempt” case. The judge’s decision is dependent on available proof. Therefore, in al-Mahloul’s case, it is the judiciary’s affiliation, not the law, that will dictate the verdict. In doubt of the legitimacy and autonomy of the judiciary in the region, he added:

“Consider a judicial system that runs by the SIG’s orders and bans 300 lawyers from representing clients before courts on the pretext that the SIG does not recognize the bar association they belong to. Is such a system independent? Since when has a lawfully elected bar association had to obtain the recognition of a government that is neither elected nor attributed legitimacy by the people? And then, is the so-called SIG independent, unbound by the instructions of the Turkish coordinator? Justice is unachievable without an independent judiciary and an unaffiliated bar association.”

Opting for the pseudonym Ula, a media worker in Aleppo’s al-Bab city gave a grim account of the status of freedom of opinion and expression in areas held by the armed opposition groups. She said:

“No journalist can criticize the SIG even though it is illegitimate and does not represent the Syrian people, while it infringes on human rights and democracy [. . .]. On top of that, it continues to fail to provide citizens with basic services. This is not to forget how Türkiye forcibly appointed Abdulrahman Mustafa as the head of this government. Journalists and citizens alike dare not express their views, fearful of the armed groups in the ‘liberated areas.’ Each armed group dominates an area where they can arrest or disappear anyone without accountability.”

As for the case filed against lawyer al-Mahloul, she said:

“I and the other journalists were terrified. We could not openly share our thoughts or viewpoints that what happened was not an insult but an individual opinion in refusal of corruption.”

Slander, Libel, and Contempt in the Syrian Penal Code

The Syrian Penal Code remains enforced in areas under the SIG and affiliated armed groups. During a November 2023 interview with Radio Rozana, Abdullah Abdulsalam, the SIG’s defense minister, said that since 2017, lawyers and dissident judges have chosen to apply the Syrian Penal Code, grounding their decision in the 1950 Constitution. A large segment of Syrians considers this constitution as representative of the Syrian revolution. The minister also declared that “judicial processes in the SIG-held areas are administered by Turkish coordinators. Additionally, there is still no Higher Council of the Judiciary.”

Media activist Ula commented on this:

“Freedom of opinion is a basic human right. A person must not be censored or persecuted for their opinions or for expressing them [. . .]. Courts in the ‘liberated areas’ use the old and repressive Syrian law and have never sought to amend it.”

For his part, lawyer al-Mousa explained the terms slander, libel, and contempt as defined within the Syrian Penal Code:

“Paragraph 1 of Article 375 of the Penal Code defines slander as ‘making an allegation against someone, even if expressed in the form of a doubt or a question, which is prejudicial to the honor or dignity of the individual concerned.’ Paragraph 2 of Article 375 defines libel as ‘any derisory remark or insult and any utterance or image that maligns a person shall be deemed a vilification if it does not entail an allegation’. Libel is an assault on an individual’s dignity without attributing to that individual a specific act or incident. In its turn, Article 373 of the code defines contempt as ‘defaming by word, gesture, or threat an employee while on duty or in the course of performing their duties, or by means that express the offender’s willingness to defame [them]’.”

Al-Mousa stressed that the Syrian Penal Code considers these acts, when aimed at public individuals and institutions, an aggravating circumstance. Therefore, a harsher penalty is imposed on individuals who engage in these acts because public authorities and staffers are deemed ‘national symbols.’

Boundaries of Freedom of Opinion and Expression in International Law

International human rights standards provide guidelines as to how domestic laws can achieve a balance between the protection of the right to freedom of expression on the one hand and respect for others and the maintenance of security and public order on the other. The right to freedom of expression can only be restricted in certain limited circumstances, as provided for in Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. However, any restrictions to realize the above-mentioned legitimate objectives must meet the requirements of legality, necessity, and proportionality.

Moreover, the limitations on freedom of expression in Article 19, paragraph 3, must be approached with restraint when applied to public figures. It must first be assumed that freedom of expression is directed at their role and not to their persons while they still have access to the protection they are entitled to in the Covenant. Thus, the mere fact that certain expressions are deemed offensive to those figures is not sufficient grounds for taking punitive action.[1] In this context, the United Nations Human Rights Committee clearly points out that national laws should not provide for stricter penalties based on the targeted individual’s legal identity as a public figure exercising official duties delegated by authorities.[2]

Addressing the margins of freedom of expression in Syria, lawyer Abdullah al-Ali, from Idlib’s Ma’arat al-Nu’man city, said:

“In all countries, you can criticize a ministry and also the head of the state without personalization, however. [Only in our country], criticism turns into desecration of homeland and national symbols, as if homeland can be reduced to merely the persons in charge.”

Notably, Amnesty International emphasizes that “imprisonment is never an appropriate penalty for defamation. Civil damages are sufficient to redress harm to individuals’ reputations.” This was reiterated by Yasser Omar Hilal, a local from Aleppo’s countryside. He said:

“I support Mr. Yasser al-Hajji’s right to file a lawsuit against the lawyer Muhammad al-Mahloul. Nevertheless, I believe the penalty must be a fine, not jail time.”

Conclusion

For decades, the Syrian government has been using these articles as a tool to suppress the freedom of opinion and expression in the country. The opposition authorities in northwestern Syria appear to have chosen to follow the same path. This continues to hamper and jeopardize the work of journalists, lawyers, and civil society activists, keeping them gagged and afraid to speak out, especially when it comes to influential figures, while also perpetuating tyranny and the repression of liberties. These were the practices Syrians have revolted against in the first place.

Should the SIG be willing to apply the law to all those who reside in its areas of influence without discrimination or preferential treatment, as it claims, it must, above all, achieve the independence of the judiciary in those areas. It is unacceptable that Syrian judges be nominated and paid their salaries by the Turkish government, nor that it selects and trains the police. The SIG should also remedy the failure of the administrative and operational structures in the area, which are largely ineffective and unable to address grievances regarding the unlawful conduct of dozens of armed groups affiliated with it.[3]

[1] Human Rights Committee, General comment No. 34: Article 19-Freedoms of opinion and expression, CCPR/C/GC/34, 12 July 2011, Para. 38.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic, A/HRC/40/70, 31 January 2019, Para. 70.