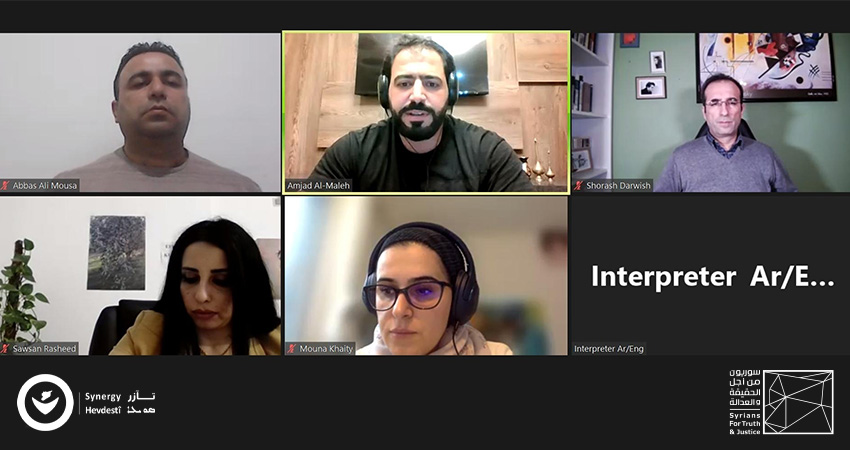

Syrians for Truth and Justice (STJ) and Synergy organizations held a virtual dialogue session on 19 October entitled “Impact of International Agreements on Civilians; Forced Displacement, Property Rights Violations, and Challenges to Safe, Voluntary Return.”

The session centered on the implications of the 2018 Russian-Turkish agreement on the population of Afrin and Eastern Ghouta, the 2017 Four Towns Agreement on the people of al-Zabadani, Madaya, Foua, and Kafarya, and the 2019 Türkiye-U.S. and Türkiye-Russia agreements on the people of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî. Attendees of the session were locals of affected areas as well as human rights activists and workers in local and international civil society organizations. The interventions elaborated on the challenges those displaced by the agreements are facing in the new communities, concerns about the future, and suggestions to mitigate the impacts of these agreements.

The session was held in the context of a project STJ and Synergy carried out in the last few months with support from the German Adopt a Revolution initiative. The project included interactive dialogue sessions with different categories of forcibly displaced people in Syria to discuss how international agreements have affected their lives and the human rights violations they have undergone due to these agreements, especially the housing, land, and property rights violations.

Session participants also made recommendations that may mitigate the effects of these agreements, prevent further radicalization of the resulting demographic change, and achieve social peacebuilding.

As part of the project, three comprehensive reports were issued that examined the role of international agreements in forced displacement. The first report analyzed the Eastern Ghouta-Afrin swap Agreement, the second addressed the Four Towns Agreement, and the third reflected on the Türkiye-U.S. and Türkiye-Russia Agreements on Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî. These reports offered valuable recommendations and legal opinions on the subject.

Topics of the Session

The first topic touched on the undisclosed Türkiye-Russia Agreement, which led to the displacement of Afrin and Eastern Ghouta’s original population in 2018. Mona Khaity, a gender and public health researcher, and Sawsan Rasheed, a human rights activist, made interventions to this topic.

Mona elaborated on the forcible displacement of the Eastern Ghouta people and the crippling years-long siege and heavy bombardment they were subjected to by the Syrian government and Russian allies before that. She pointed out that Eastern Ghouta people were unaware that their displacement was concluded in an agreement and did not know where they were to deport.

After Eastern Ghouta people settled in northern Syria, they faced several adverse conditions. They did not find safety or stability due to the periodic bombardment of their areas, which forced them into repeated displacement. Moreover, Eastern Ghouta people in northern Syria suffer poor services, especially in health and education, while those who went to Türkiye suffer the prevalent racism against Syrians.

Mona noted that the displacement has had additional consequences for women due to the breakdown of social structure and the lack of protection from their original communities. Women, especially those whose husbands died or disappeared, have to go through very complex procedures to access their real estate.

Mona said housing, land, and property rights constitute a highly complex issue in all Syrian parts. She affirmed that all the forcible displacements aimed at demographic change and discord between Syrians. Concentrating Eastern Ghouta IDPs in Afrin incited ethnic and regional strife and created a deep gap between Afrin’s original people and the displaced, Mona concluded.

For her part, human rights activist Sawsan Rasheed spoke on the current condition of Afrin’s original people and how they were affected by the 2018 Turkish offensive, whose repercussions are continued.

Sawsan pointed out that because of the acts of looting, destruction, and seizure of property that occurred in Afrin, many of the displaced refrained from returning despite the end of the military operations. Moreover, arbitrary arrests, enforced disappearances, and torture over allegations of having links with the Autonomous Administration and affiliating with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) prompted the last Afrininans to leave.

The displaced were obliged to live in camps a few kilometers away from their villages. These camps are not recognized by the United Nations and suffer deplorable conditions and limited employment opportunities. However, some IDPs headed to Aleppo, where they stayed in Sheikh Maqsoud and Ashrafiyye neighborhoods, which are uninhabitable being %60 devastated and surrounded by checkpoints of the 4th Armoured Division, which blocks the entry of medicine and fuel. As for those displaced to the Syrian Jazira, they live under harsh economic conditions and pay high rents for homes, the minimum of 100$, according to Sawsan.

The second topic was the impacts of the Türkiye-U.S. and Türkiye-Russia Agreements on the people of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî. Under this topic, writer and researcher Shoresh Darwish narrated the events preceding and after the implementation of the two agreements that facilitated Türkiye’s Operation Peace Spring of 9 October 2019. The Operation resulted in Türkiye’s full control over the Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê and Tell Abyad/Girê Sipî and parts of their surroundings, reaching the M4 highway, which lies 30 to 35 km deep in Syrian territory. It was suspended under two separate agreements Türkiye signed with the United States (U.S.) and Russia on 17 and 22 of the same month.

This was followed by Donald Trump’s declaring withdrawal from Syria, on which he commented, “Let someone else fight over this long bloodstained sand”. The then Washington collusion with Türkiye’s policies in the area generated statements of the same notion by presidents of the two countries; Trump’s tweet, “Let them go to the south or to desert”, referring to Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê people, was followed by a statement by Recep Tayyip Erdoğan saying, “The ]desert[ nature of Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê is not suitable of the Kurdish lifestyle”.

Shoresh warned that if the Turkish occupation lasted longer, Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê would lose its religious and ethnic diversity, which characterized it for ages. Ras al-Ayn/Serê Kaniyê once had Syriac, Assyrian, Armenian, Chechen, Arab, Kurdish, and Turkmen living in coexistence.

Shoresh considered that the worst thing about these two agreements was that they did not touch upon the fate of locals or the return of the displaced, especially those in makeshift camps. He criticized the U.S. silence on Türkiye’s offensives into northeastern Syria and the involved bombardments that killed and displaced many innocents.

The third topic addressed the Four Towns Agreement under which al-Zabadani, Madaya, Foua, and Kafarya were evacuated.

On this topic, civil activist Amjad al-Maleh confirmed that the last locals in al-Zabadani and Madaya are facing conscription, the spread of drugs under the cover of Lebanese Hezbollah and facilities by the Syrian regime, and poor security conditions. Furthermore, agricultural lands in the two towns, whose crops once supplied all of Syria, were used to grow cannabis.

Amjad confirmed that those displaced to northwestern Syria are having great difficulties in integrating into new communities, which lack common national identity and are dominated by subnational tribal, religious, partisan, and factional identities.

In addition to complex social conditions, displaced individuals face economic hardship due to uncompensated losses from agreements and difficulties accessing inheritance and restoration without any redress plan in sight, as Amjad concluded.